INTRODUCTION

In the last 50 years obesity rates have substantially increased in Mexico, showing a drastic increase in body mass index (BMI) among the population as a result of evolving dietary habits (1). The exact prevalence of obesity in Mexico is not well known and varies among sources, but more than 30% of Mexico’s population are obese according to the most recent update of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2). Obesity is associated with several diseases, such as coronary heart disease, high blood pressure, and diabetes (3). The association of obesity and other previously mentioned conditions represents a widely known disorder characterized by the presence of multiple risk factors, and known as metabolic syndrome (4). This disorder is diagnosed when at least three of the following are present: central obesity, hyperglycemia, hypertriglyceridemia, low HDL-cholesterol, and hypertension (5). The last nutritional survey in Mexico (ENSANUT, from its Spanish acronym, 2012) reported that metabolic syndrome had increased to 45% (6) as compared to the report published in 2006 (7).

On the other hand, worldwide leading causes of death according to the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Global Health Observatory include ischemic heart disease, stroke, lower respiratory infection, and chronic obstructive lung disease; however, cancer has also become a leading cause of mortality, causing 1.6 (2.9%) million deaths in 2012. Mortality rates in Mexico are no different, as cancer is the second or third leading cause of death, with approximately 78,000 cancer deaths in 2012 (8). Nonetheless, Mexico does not track morbidity data. Official sources only provide data on the number of hospital discharges from public institutions without identification of patient cases (9).

As both metabolic syndrome and cancer have become public health problems worldwide, and their association has been widely studied mostly in developed countries (10 11-12), the aim of this study was to identify the overall prevalence of metabolic syndrome and to describe its characteristics among first-time cancer patients at a referral center in Mexico.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This is a prospective, observational, cohort study of first-time patients of the National Cancer Institute of Mexico (INCan, from its Spanish acronym), from September 2016 to September 2017. The study was approved by the institutional ethics and research committees. All participants provided their written informed consent.

PATIENTS AND DATA

We identified 1,165 first-time patients at the INCan during a 1-year period. We enrolled 316 patients who met the eligibility criteria. Inclusion criteria included: known or recently diagnosed metabolic syndrome, ≥ 18 years of age, and good performance status. Clinical and demographic data, such as gender, age, and type of cancer were collected from the electronic medical records (INCanet). All patients underwent a complete nutritional evaluation to assess the presence of metabolic syndrome.

DEFINITION OF METABOLIC SYNDROME AND MEASUREMENTS

For the diagnosis of metabolic syndrome, the latest harmonized definition (5) was used, which requires the presence of three or more of the following: waist circumference ≥ 80 cm in women and ≥ 94 cm in men; triglycerides ≥ 150 mg/dL; HDL-cholesterol < 50 mg/dL; fasting glucose ≥ 100 mg/dL or diabetes treatment; systolic blood pressure ≥ 130 mm Hg, and diastolic blood pressure ≥ 85 mm Hg or antihypertensive drug treatment.

Blood pressure (BP), weight (kilograms, kg), and height (centimeters, cm) were obtained, and body mass index (BMI) was calculated: weight in kilograms divided by square height in meters (kg/m2). The waist-hip (W-H) ratio was obtained as waist measurement divided by hip measurement. Any previous history of dyslipidemia and diabetes mellitus (DM) was also recorded. Patients were sent to the laboratory for serum determinations of fasting glucose and a lipid panel.

RESULTS

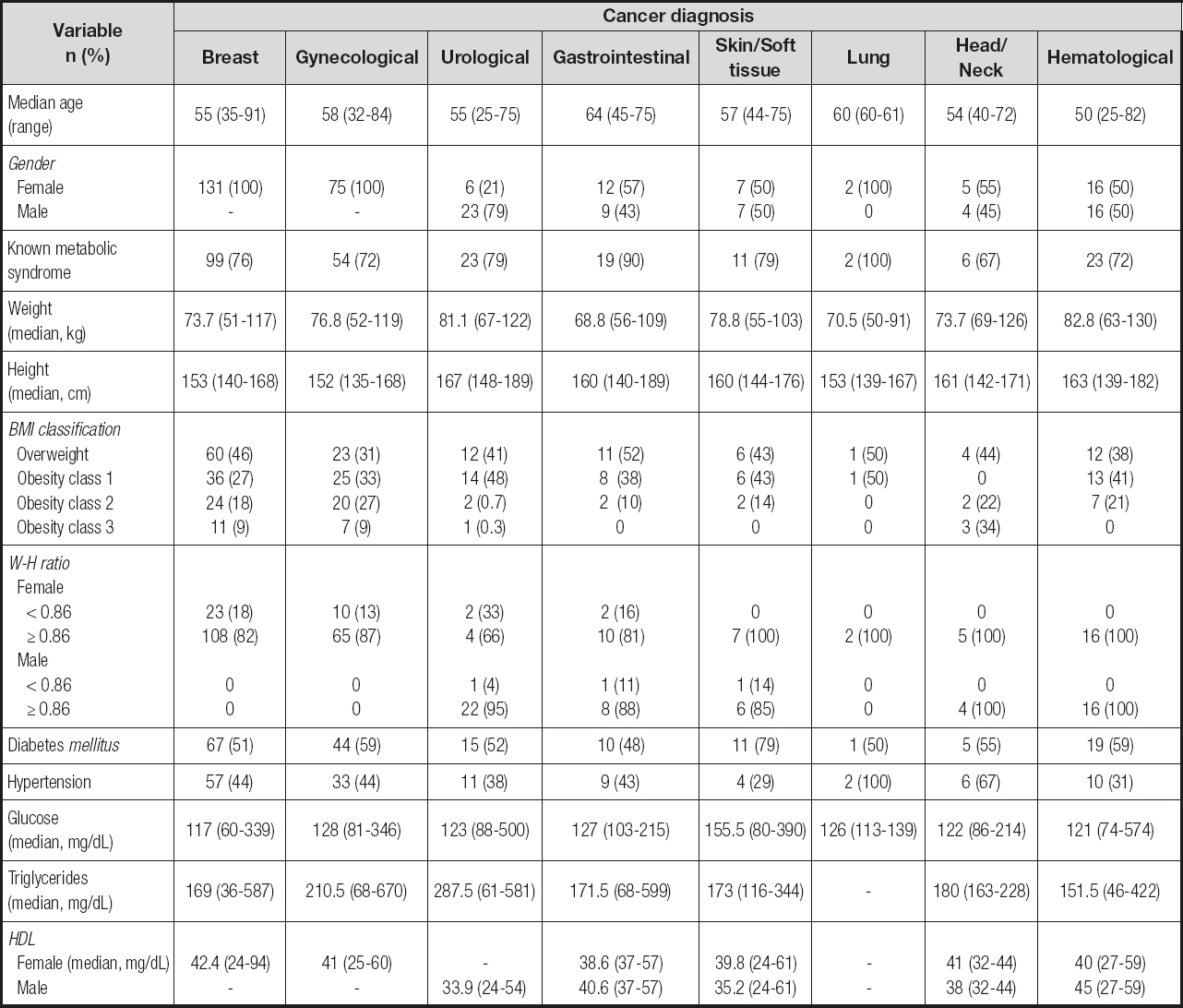

We identified 1,165 patients with cancer, and the incidence of metabolic syndrome according to the underlying cancer was as follows: breast (n = 131/361, 36%), gynecological (n = 75/211, 35%), gastrointestinal (n = 21/208, 10%), hematological (n = 32/126, 25%), urological (n = 29/72, 40%), soft tissue/skin (n = 14/31, 45%), head and neck (n = 9/120, 8%), and lung (n = 2/36, 6%); therefore, out of the 1,165 patients identified at the INCan, the final cohort included 316 patients (27%) with metabolic syndrome. Median age was 55 years (range, 25-91). The majority were women (n = 254, 81%; men, n = 59, 19%). Most frequent tumors included breast, gynecological, and hematological neoplasms: 42%, 24%, and 10%, respectively. Most patients were overweight (n = 130, 42%); median weight and height were 155 cm and 76 kg, respectively. Median BMI and W-H ratio were 31 and 0.92, respectively. Fifty-five percent of patients had diabetes mellitus (n = 172), and 42% had hypertension (n = 132). Before referral to our institution, 237 patients (76%) had already been diagnosed with metabolic syndrome and 76 patients (24%) were diagnosed at admission. Median laboratory parameters were as follows: glucose 121.5 mg/dL, triglycerides 185.5 mg/dL, HDL-cholesterol 41 mg/dL, total cholesterol 181 mg/dL, and LDL-cholesterol 117.6 mg/dL. Obesity (class 1-3) was mostly observed in patients with skin and soft tissue, hematological, and urological tumors: 69%, 63%, and 59%, respectively. Abnormal glucose and/or previous DM diagnosis were mostly observed in patients with skin and soft tissue, gynecological, and gastrointestinal tumors: 86%, 58%, and 57%, respectively. Dyslipidemia, high triglycerides, and/or low HDL-cholesterol were mostly observed in patients with gastrointestinal, skin and soft tissue, and urological tumors: 100%, 76%, and 71%, respectively. Patients with head and neck, gynecological, and breast tumors were those most frequently seen with known or recently diagnosed hypertension: 67%, 44%, and 44%, respectively. The overall characteristics by diagnosis are shown in table I.

DISCUSSION

Several studies and meta-analyses (13 14-15) have demonstrated that common cancers, such as gastrointestinal, breast, pancreatic, and gynecological neoplasms, are associated with metabolic syndrome. However, to date, the mechanisms linking this disorder and cancer are not completely understood, as it is unknown whether the strength of the association between these is greater than the sum of the individual components of metabolic syndrome, which might be driving this association, or whether the metabolic syndrome is a reliable predictor of cancer risk (11). Metabolic syndrome might represent a surrogate marker for other cancer risk factors: sedentary lifestyle, high dietary fat and carbohydrate intake, and oxidative stress (5,10). On the other hand, overweight and obesity are currently very important challenges of public health worldwide, and their negative effect among chronic, non-communicable diseases such as cancer is widely known (18). Mexico has the second highest global prevalence of obesity in the adult population, which implies a major challenge for the health sector (18). Moreover, the most frequent types of cancer in Mexican adults are breast and gastrointestinal tumors in women and men, respectively. Although metabolic syndrome and its association with cancer are topics of interest, data in Mexico and other developing countries where obesity is high remain scarce. A study found a prevalence of MS in 27% of Mexican female survivors of cancer (19); furthermore, a study performed in women with breast cancer reported a prevalence of 50% among obese women (20). Osornio-Sánchez et al. (21) reported a prevalence of 48% among patients with prostate cancer. In this study, we identified a prevalence of metabolic syndrome in 27% of first-time patients of the INCan during a 1-year period. Prior to referral to our Institution, 76% of patients were already diagnosed with metabolic syndrome, which highlights the importance of primary care. Our results showed that breast, gynecological, urological, and soft tissue/skin cancers have the highest prevalence of metabolic syndrome.

Due to the high prevalence of MS and the high incidence of cancer worldwide, it is assumed by some authors that many cases of cancer should be attributed to MS (22). Mexico is no exception, and an implementation of preventive strategies for MS patients, focusing on the first level of care during early stages in order to reduce the risk of cancer, is needed. As we acknowledge the limitations of our study–one center, small cohort due to the 1-year period–we also highlight that this is the first study performed in Mexican patients including all types of cancer and reporting the prevalence of metabolic syndrome among them. More studies in Mexican patients and other developing countries with high incidence of obesity and metabolic syndrome are encouraged for further comparisons.