Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Anales de Psicología

versión On-line ISSN 1695-2294versión impresa ISSN 0212-9728

Anal. Psicol. vol.31 no.2 Murcia may. 2015

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.31.2.177961

Spanish Adaptation of the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI). Psychometric properties of the patient and therapist forms (WAI-P and WAI-T)

Adaptación española del Working Alliance Inventory (WAI). Propiedades psicométricas de las versiones del paciente y del terapeuta (WAI-P y WAI-T)

Nelson Andrade-González and Alberto Fernández-Liria

Universidad de Alcalá (Spain)

ABSTRACT

The working alliance is one of the most widely studied constructs in psychotherapy process research. The purpose of our study was to adapt the patient and therapist forms of the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI-P and WAI-T) into Spanish. Both measurement instruments were translated into Spanish through a systematic translation process. The psychometric properties of the instruments were evaluated in both a pilot study and a clinical study involving Spanish outpatients with depressive disorders and their therapists. In the clinical study, patients completed the Spanish-language Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) prior to initiating therapy and after the third and tenth psychotherapy sessions. High average scores were obtained with the Spanish-language WAI-P and WAI-T. A large number of individual items correlated satisfactorily with the overall score for the corresponding subscale. Both measures demonstrated excellent reliability (internal consistency) and convergent validity. There were some limitations in the discriminant validity of the measures vs. measures of empathy. Regarding predictive validity, the overall WAI-P and the Task subscale of the WAI-T separately explained a moderate percentage of the variance in patient change in the BDI after the tenth psychotherapy session. These results were satisfactory and consistent with those obtained in studies using the English-language WAI.

Key words: Spanish adaptation; Working Alliance Inventory, WAI.

RESUMEN

La alianza de trabajo es uno de los constructos mas estudiados en investigacion de procesos en psicoterapia. El objetivo de nuestra investigacion fue adaptar las versiones del paciente y del terapeuta del Working Alliance Inventory (WAI-P y WAI-T) a la lengua espahola. Ambos instrumentos de medida fueron traducidos al espahol mediante un proceso reglado de traduccion. Sus propiedades psicometricas fueron examinadas en un estudio piloto y en un estudio clinico en el que participaron pacientes ambulatorios con trastornos depresivos y sus correspondientes terapeutas. En el estudio clinico, los pacientes completaron la adaptacion espahola del Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) antes del tratarmento y despues de la tercera y de la decima sesion de psicoterapia. El WAI-P y el WAI-T en espahol exhibieron altas puntuaciones medias. Un elevado numero de sus items correlaciono de manera adecuada con la puntuacion total de su respectiva subescala. Ambas pruebas evidenciaron una excelente fiabilidad (consistencia interna) y una excelente validez convergente. Su validez discriminante exhibio algunas limitaciones cuando ambas medidas correlacionaron con dos pruebas de empatia. En cuanto a la validez predictiva, el WAI-P total y la subescala tareas del WAI-T explicaron por separado un porcentaje moderado de la varianza del cambio de los pacientes en el BDI despues de la decima sesion de psicoterapia. Estos resultados fueron satisfactorios y coherentes con los hallados en los estudios que han empleado las correspondientes versiones originales del WAI en ingles.

Palabras clave: Adaptacion española; Working Alliance Inventory, WAI.

Introduction

The therapeutic or working alliance has aroused the interest of therapists and researchers in recent decades and is one of the most widely studied constructs in psychotherapy process research. According to Bordin (1979) the working alliance has three components: therapist-patient agreement regarding the goals of psychotherapy; therapist-patient agreement regarding the tasks to be completed in psychotherapy; and therapist-patient bond, which "is likely to be expressed and felt in terms of liking, trusting, respect for each other, and a sense of common commitment and shared understanding in the activity" (Bordin, 1994, p. 16).

Bordin's alliance model stimulated intense research that continues to the present day and which laid the foundations for Horvath to create the Working Alliance Inventory (WAI; Horvath, 1981; Horvath & Greenberg, 1986, 1989). The patient form (WAI-P) and therapist form (WAI-T) of the WAI consist of 36 items organized into three subscales (Bond, Goal, and Task) of 12 items each. Users respond to each item using a seven-point Likert scale.

The WAI-P and WAI-T are the most widely used alliance measures in individual psychotherapy (Hill & Lambert, 2004), likely because the items are easily understood, not too long, and not tied to any particular theoretical school of psychotherapy, and because the instruments have solid psychometric properties (Andrade-González, 2005). In terms of their reliability (internal consistency), the development study of the WAI (Horvath, 1981) (N = 29 patients and 29 therapists) revealed that the Cronbach's alpha coefficients of the overall WAI-P and WAI-T were .93 and .87, respectively, while the Hoyt reliability indices of the subscales were .85.88 (WAI-P) and .68-.87 (WAI-T). Hanson, Curry, & Bandalos (2002) reviewed studies that had used both alliance measures in English and found that the mean alpha coefficients of the overall WAI-P and WAI-T were .93 and .91, respectively, and the mean alpha coefficients of the corresponding subscales were .87-.89 (WAI-P) and .84-.90 (WAIT).

In terms of construct validity, the results of a multi-trait/multi-method matrix built by Horvath (1981) showed convergent validity of all WAI subscales and partially demonstrated discriminant validity of the Goal and Task subscales but not the Bond subscale (Horvath, 1981; Horvath & Greenberg, 1989). Nevertheless, the limited correlations found by Horvath (1981) among the three subscales of the WAI-P and the three subscales of the Counselor Rating Form (used by patients to rate the therapist's attractiveness, trustworthiness, and expertise) (LaCrosse & Barak, 1976; LaCrosse, 1980) confirmed the discriminant validity of the three subscales of the WAI-P (Horvath, 1994). In addition, the large, significant correlations seen in later studies between the WAI-P or WAI-T and other measures of alliance provide additional evidence for the convergent validity of both versions of the WAI. In terms of the factorial structure of the WAI-P and WAI-T, the few studies that have considered it have found different factorial compositions for the two measures.

Finally, in terms of criterion validity, Horvath's (1981) and subsequent studies (Horvath, Del Re, Flückiger, & Symonds, 2011) found moderate correlations between the WAI-P or WAI-T and the results of different psychotherapeutic treatments. These findings underscore the utility of the English-language WAI-P and WAI-T in psychotherapeutic process research.

The aim of this study was to adapt the WAI-P and WAIT for use with and by Spanish-speaking people, because the English-language versions of these measures have been used widely in more than two decades of psychotherapeutic research. To this end, a systematic translation of the WAI-P and WAI-T into Spanish was carried out, a pilot study was designed to assess how well both translations worked, and finally a wider-reaching clinical study was performed to examine their main psychometric properties. In this regard, the reliability (internal consistency) and validity (construct and criterion validities) of the Spanish-language WAI-P and WAI-T were tested. Evidence for the construct validity of both alliance measures was derived from the analysis of correlations between each measure's subscales, correlations with another alliance measure, and correlations with various demographic variables and an empathy measure. For its part, evidence for the criterion validity was derived from the analysis of correlations between the Spanish-language WAI-P and WAI-T and the change undergone by patients treated with psychotherapy. As such, it was our hope that the Spanish-language versions would demonstrate similar reliability and validity to the English-language originals.

Methods

Legal requirements

Professor Adam O. Horvath of Simon Fraser University (Canada) gave us permission to use the WAI for this research. The limited copyright license number was 200457.78.

Translation of the WAI-P and WAI-T into Spanish

Two professional Spanish translators carried out a forward and backward translation of the WAI-P and WAI-T. Subsequently, four Spanish psychotherapy experts examined the preliminary Spanish translation. For the instructions and each of the 36 items of each measure, the experts indicated their level of understanding on a 10-point scale. When they felt it was necessary, they proposed a maximum of three edited versions of the text that they believed were more understandable. The instructions and items of the preliminary Spanish versions were considered acceptable if they met two criteria: they were rated "10" on the understanding scale by all four experts, and they elicited no suggested edits from the experts. Fifteen WAI-P items and 11 WAI-T items met these criteria. For the instructions and other items, the experts' suggested edits were combined and incorporated into the measures. The experts then reviewed the reformulated instructions and items. The instructions of both versions passed this second review, as did 14 WAI-P items and 17 WAI-T items. For the remaining items, the translators and the main author of this study agreed upon the best translation. Finally, two linguists from the University of Alcala reviewed both measures and reported that they could be understood by most Spanish-speaking people.

Pilot study

After their third psychotherapy session, 10 outpatients with depressive disorders referred to three Spanish public health centers filled out the Spanish-language WAI-P, and 10 integrative therapists filled out the Spanish-language WAI-T. The patients and therapists were unaware of each other's responses.

Based on the corrected item-total correlations for all items from these two measures, their reliability (internal consistency), and the therapists' opinions, some changes were made to the questionnaires. First, the word "not" in some negative items was highlighted (eight items from the WAI-P and seven from the WAI-T). Second, eight items from the WAI-P and two from the WAI-T were reworked. Two linguists from the University of Alcala approved all reworked items.

Clinical study

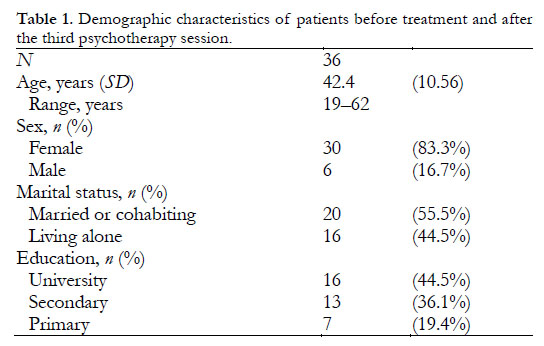

Participants. Thirty-six outpatients who were referred to five Spanish public health centers filled out questionnaires (see below) both before treatment and after their third psychotherapy session. Table 1 shows their demographic characteristics. According to the therapists, 31 of them (86.1%) met the DSM-IV-TR (American Psychiatric Association, 2002) diagnostic criteria for a major depressive disorder (single or recurrent episode, with no psychotic or catatonic symptoms) and five (13.9%) met the conditions for a dysthymic disorder. Of these 36 patients, 30 filled out questionnaires again after the tenth session. No patient received any incentive for taking part in this research.

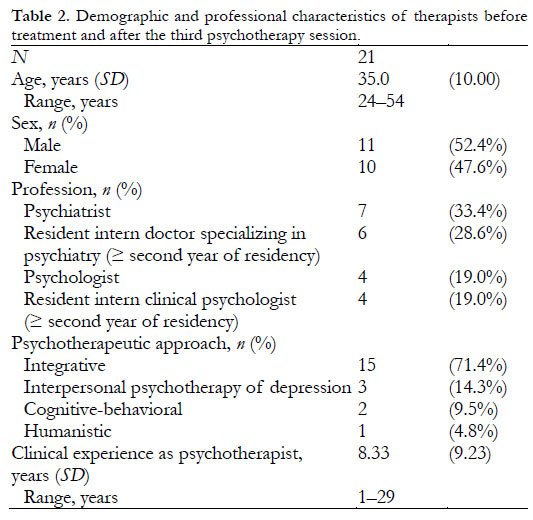

Twenty-one therapists filled out questionnaires both before treatment and after the third psychotherapy session. Table 2 shows their demographic and professional characteristics.

Of them, 16 filled out questionnaires again after the tenth session. All therapists offered their services at Spanish public health centers. Of the 21 therapists taking part in the study before treatment and after the third psychotherapy session, 15 treated one patient each, four treated two patients each, one treated six patients, and one treated seven patients. Of the 16 therapists taking part in the study after the tenth session, 11 treated one patient each, three treated two patients each, one treated six patients, and one treated seven patients.

Treatment. The patients underwent individual psychotherapy sessions as their main form of outpatient treatment. The psychotherapy sessions were 1 hr long. During the first three psychotherapy sessions, 30 patients were treated with integrative psychotherapy, three with interpersonal psychotherapy of depression, two with cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy, and one with humanistic psychotherapy. Later, four patients dropped out of treatment (three had been treated with integrative psychotherapy, and one with humanistic psychotherapy). In addition, two patients treated with integrative psychotherapy were excluded from the analysis because the therapist who had been treating them moved to another health center. The patients were not assigned randomly to these treatment conditions. Patient and therapist ratings were taken through the end of the tenth psychotherapy session.

Measures. A number of measures were used, as described below.

Spanish-language Working Alliance Inventory, Patient form (WAI-P). The WAI-P (Horvath, 1981; Horvath & Greenberg, 1986, 1989) measures the therapeutic alliance as perceived by the patient. It consists of 36 items with seven possible response options (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = occasionally, 4 = sometimes, 5 = often, 6 = very often, 7 = always). WAI-P items 1, 20, and 29 (Bond); 3, 9, 10, 12, 27, and 34 (Goal); and 7, 11, 15, 31, and 33 (Task) are written in the negative. Scores for the negative items are inverted before calculating the total WAI-P alliance score or a subscale score (sum of the scores of 36 or 12 items, respectively). The scoring range of the overall WAI-P is 36-252 points. The items on the Spanish-language WAI-P are set out in Appendix A.

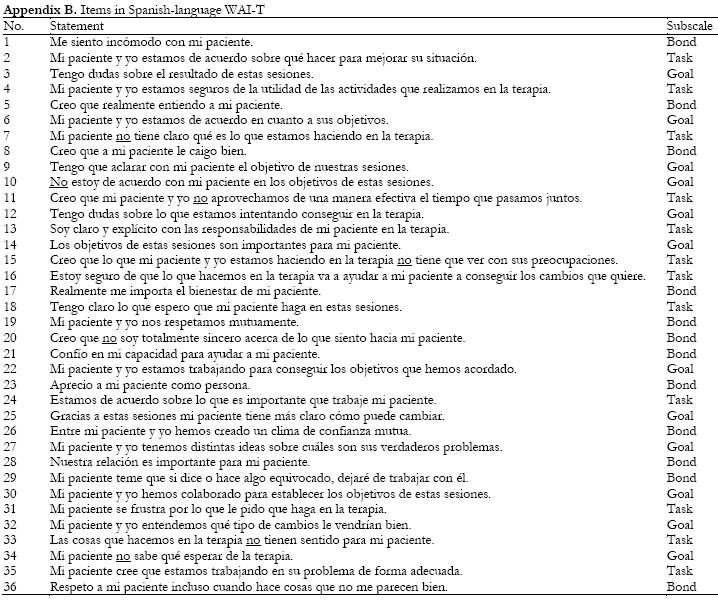

Spanish-language Working Alliance Inventory, Therapist form (WAI-T). The WAI-T (Horvath, 1981; Horvath & Green-berg, 1986, 1989) measures the therapeutic alliance as perceived by the therapist. It consists of 36 items with seven possible response options (1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = occasionally, 4 = sometimes, 5 = often, 6 = very often, 7 = always). WAI-T items 1, 20, and 29 (Bond); 3, 9, 10, 12, 27, and 34 (Goal); and 7, 11, 15, 31, and 33 (Task) are written in the negative. Calculating the total WAI-T alliance score or a subscale score follows the process described above for the WAI-P. The scoring range of the overall WAI-T is 36-252 points. The items on the Spanish-language WAI-T are set out in Appendix B.

Spanish-language Revised Helping Alliance Questionnaire, Patient form (HAq-II-P; Andrade-González, 2009). The HAq-II-P (Luborsky et al., 1996) measures the therapeutic alliance as perceived by the patient. It consists of 19 items with six possible response options ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The scoring range of the overall HAq-II-P is 19-114 points. The reliability (internal consistency) for the HAq-II-P in the current sample was excellent (Cronbach's α = .88). The corrected item-total correlations were > .30 for 18 of the 19 items (94.7%). For item 17, the corrected item-total correlation was .22.

Spanish-language Revised Helping Alliance Questionnaire, Therapist form (HAq-II-T; Andrade-González, 2009). The HAq-II-T (Luborsky et al., 1996) measures the therapeutic alliance as perceived by the therapist. It consists of 19 items with six possible response options ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The scoring range of the overall HAq-II-T is 19-114 points. The reliability (internal consistency) for the HAq-II-T in the current sample was excellent (Cronbach's α = .93). The corrected item-total correlations were > .30 for 18 of the 19 items (94.7%). For item 11, the corrected item-total correlation was .30.

Spanish-language Empathic Understanding Scale of the Relationship Inventory, Patient form (EUS-P; Andrade-González 2009). The EUS-P (Barrett-Lennard, 1978) measures the patient's perception of his or her therapist's empathy. It consists of 16 items with six possible response options ranging from 1 (no, I strongly feel that it is not true) to 6 (yes, I strongly feel that it is true). The scoring range of the overall EUS-P is 16-96 points. The reliability (internal consistency) for the EUS-P in the current sample was excellent (Cronbach's α = .91). The corrected item-total correlations were > .30 for all items (100%).

Spanish-language Empathic Understanding Scale of the Relationship Inventory, Therapist form (EUS-T; Andrade-González, 2009). The EUS-T (Barrett-Lennard, 1978) measures the therapist's perception of the empathy he or she has shown toward the patient. It consists of 16 items with six possible response options ranging from 1 (no, I strongly feel that it is not true) to 6 (yes, I strongly feel that it is true). The scoring range of the overall EUS-T is 16-96 points. The reliability (internal consistency) for the EUS-T in the current sample was excellent (Cronbach's α = .92). The corrected item-total correlations were > .30 for 15 of the 16 items (93.8%). For item 7, the corrected item-total correlation was .22.

Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), revised version (Beck, Rush, Shaw, & Emery, 1979; Beck & Steer, 1993), Spanish adaptation (Sanz & Vázquez 1998; Vázquez & Sanz, 1997, 1999). The revised BDI measures the intensity of depression. It consists of 21 items with four possible response options (0, 1, 2, or 3) arranged in order of intensity. The scoring range of the overall BDI is 0-63 points. Previous studies have demonstrated that the Spanish adaptation of the BDI is a psycho-metrically sound instrument with good reliability (internal consistency) (Sanz & Vázquez, 1998; Vázquez & Sanz, 1997, 1999). In the current sample, Cronbach's α of .82, .90, and .91 were obtained for the BDI at baseline, third session, and tenth session, respectively.

Procedure. Before treatment the patients filled out the BDI as a screening tool. Therapists interviewed patients who scored ≥ 12 points to select those who met the DSM-IV-TR criteria (American Psychiatric Association, 2002) for a major depressive disorder or a dysthymic disorder. The selected patients who decided to participate in this study provided written consent and filled out a demographic data sheet. At the same time, their therapists separately filled out a demographic data sheet. After the third psychotherapy session, the patients filled out the BDI, WAI-P, HAq-II-P and EUS-P while their therapists filled out the WAI-T, HAq-II-T, and EUS-T. After the tenth psychotherapy session, the patients filled out the BDI, and WAI-P while their therapists filled out the WAI-T. The patients and therapists were unaware of each other's responses. At the end of the tenth session, patients completed the BDI to evaluate the predictive validity of both Spanish versions of the WAI.

Data analysis. The data analysis was carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS v.17) and R (v.2.11). Scores on the negative items of the WAI-P, WAI-T, HAq-II-P, HAq-II-T, EUS-P, and EUS-T were inverted. One therapist did not respond to any items on the HAq-II-T. This case was not used in the data analysis. There were a few individual unscored items across the different measures. For these items the participant's mean score on the corresponding subscale or scale was used as a substitute. Two variables were dichotomized: the patients' marital status (coded as married/cohabiting or not) and the therapists' initial training (medicine or psychology). The normality of the variables with 30 cases was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test. After the tenth psychotherapy session, the WAI-P (total and subscales) and the overall WAI-T (and its Bond and Goal subscales) were not normally distributed. The homoscedasticity of all variables was evaluated using the Levene test. The null hypothesis of homogeneity of variance was not rejected for any variable. The corrected item-total correlations of the WAI-P and WAI-T items were obtained by correlating the scores for each item with the total score for their respective subscale minus that item. Cronbach's alpha (a) coefficient was used to determine the reliability (internal consistency) of both alliance measures. As for the construct validity of the WAI-P and WAI-T, Pearson's correlation coefficients were used to estimate the relationship between their subscales after the third psychotherapy session, and Spearman's correlation coefficients were used after the tenth session. The convergent validity of the WAI-P and WAI-T (total and subscales) was determined by correlating both measures with HAq-II-P and HAq-II-T, respectively, after the third psychotherapy session. Their discriminant validity was estimated by correlating the two versions of the WAI (total and subscales) with certain patient and therapist variables (for the WAI-P, three demographic variables; for the WAI-T, two demographic variables and initial training) and with EUS-P and EUS-T, respectively, after the third session. Pearson's correlation coefficients were used to determine the convergent validity and discriminant validity of the WAI-P and WAI-T. Patient change in the BDI was determined by linear regression analysis; the dependent variable was the BDI after the tenth psychotherapy session, and the independent variable was the baseline BDI. This analysis generated a new variable, the unstandardized residual BDI (M = 0.00, SD = 0.46), which reflects patients' BDI scores after the tenth psychotherapy session not accounted for by their scores on this measure at baseline. Accordingly, with respect to the criterion validity of the WAI-P and WAI-T, their predictive validity was determined by correlating scores for both versions of the WAI (administered after the third psychotherapy session) with the BDI residual gain scores, using Pearson's correlation coefficients. In depth analysis of the relationship between these variables was conducted using two stepwise linear regression analyses.

Results

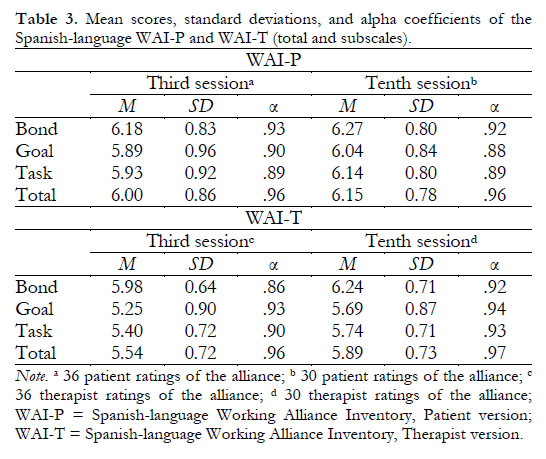

Mean scores, corrected item-total correlations, and reliability

After the third psychotherapy session, the mean scores on the Spanish-language WAI-P and WAI-T (total and sub-scales) were ≥ 5.89 and ≥ 5.25, respectively (Table 3). The corrected item-total correlations were > .30 for 35 items (97.2%) on the WAI-P. The correlation was .25 for item 11. The corrected item-total correlations were > .30 for all items (100%) on the WAI-T.

After the tenth psychotherapy session, the mean scores on the WAI-P and WAI-T (total and subscales) were ≥ 6.04 and ≥ 5.69, respectively (Table 3). The corrected item-total correlations were > .30 for 34 items (94.4%) on the WAI-P. The correlations of items 33 and 31 were .30 and .22, respectively. As before, the corrected item-total correlations were > .30 for all items (100%) on the WAI-T.

With regard to the reliability (internal consistency) of the WAI-P and WAI-T, Cronbach's alpha coefficients for both overall measures and their corresponding subscales were ≥ .86 after the third and tenth psychotherapy sessions (Table 3).

Construct validity

The correlations among the subscales of the Spanish-language WAI-P were .82-.93 (p < .01) after the third psychotherapy session and .66-.85 (p < .01) after the tenth session. The correlations among the subscales of the Spanish-language WAI-T were .81-.92 (p < .01) after the third psychotherapy session and .75-.92 (p < .01) after the tenth session. In both measures at both time points, the correlation between the Goal and Task subscales was greater than the correlation between Bond and Goal and between Bond and Task.

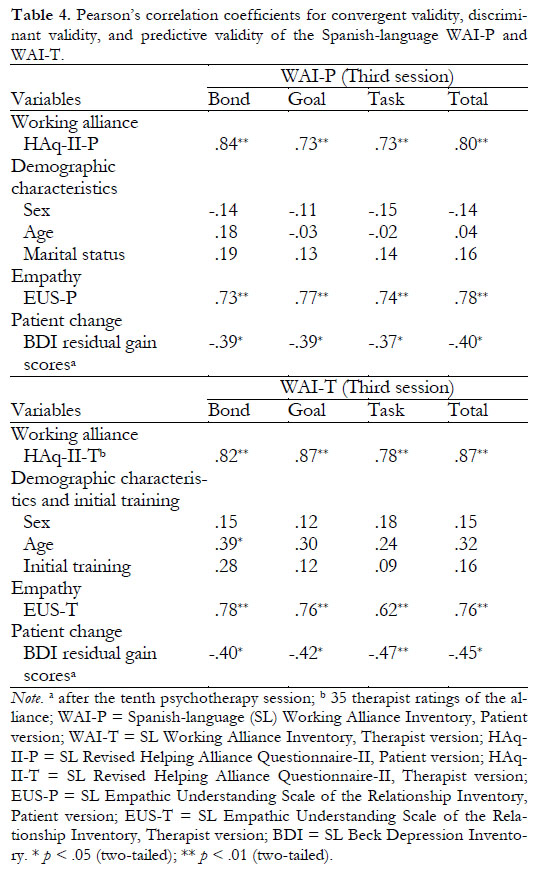

Regarding convergent validity, correlations between the WAI-P and WAI-T (total and subscales) and the HAq-II-P and HAq-II-T, respectively, were ≥ .73 (Table 4); all correlations were significant (p < .01).

Regarding discriminant validity, the WAI-P and WAI-T (total and subscales) did not correlate significantly with the majority of demographic variables for patients and therapists, respectively. Similarly, the WAI-T did not correlate significantly with the therapists' initial training. However, correlations between the WAI-P (total and subscales) and the EUS-P, and between the WAI-T (total and subscales) and the EUS-T, were ≥ .62 (Table 4); all correlations were significant (p < .01).

Criterion validity

Regarding the predictive validity of the Spanish-language WAI-P and WAI-T, correlations between the scores for both measures (totals and subscales) and the BDI residual gain scores were ≤ -.37 (Table 4); all correlations were significant (p < .01; p < .05). In a stepwise linear regression analysis, independent variables were the overall WAI-P and its three subscales administered after the third psychotherapy session, and the dependent variable was patient change in the BDI after the tenth session. Results of regression analysis revealed that the overall WAI-P predicted patient change in the BDI [F Change (1,28) = 5.26, R2 Change = .16, p = .03]. In a second analysis of this kind, independent variables were the overall WAI-T and its three subscales administered after the third psychotherapy session, and the dependent variable was patient change in the BDI after the tenth session. This second analysis revealed that the WAI-T Task subscale predicted patient change in the BDI [F Change (1,28) = 7.98, R2 Change = .22, p = .01]. Hence, the overall WAI-P and the Task subscale of the WAI-T separately explained 16% and 22%, respectively, of the variance in patient change in the BDI.

Discussion

The psychometric properties of the Spanish-language WAI-P and WAI-T are acceptable, although there are some shortcomings in terms of construct validity. The mean overall scores on the WAI-P and WAI-T were high and consistent with those found in studies involving these original (English-language) versions of the WAI. In a meta-analysis Tryon, Blackwell, & Hammel (2008) found that the mean scores on the English-language WAI-P and WAI-T represented 80.9% and 75.77%, respectively, of the total alliance scores on these measures. The corrected item-total correlations of > .30 for a large proportion of the items on the Spanish-language WAI-P and WAI-T indicates that these elements correlate satisfactorily with the total of their respective subscales. The reliability (internal consistency) of the Spanish-language WAI-P and WAI-T were excellent according to the criteria of Muhiz (2005), as there was strong covariance between the items in each overall measure and the items of the corresponding subscales. These reliability results are consistent with those reported in studies involving the English-language versions of the WAI (Hanson et al., 2002).

Regarding construct validity, the correlations between the subscales of the Spanish-language WAI-P and WAI-T were high. This is likely due to the fact that the three components of alliance (bond, goals, and tasks) influence one another (Safran & Muran, 2000). That is, the quality of the patient-therapist bond influences the level of agreement in the goals and tasks of psychotherapy, and this level of consensus determines the strength of the bond (Safran & Muran, 2000). The correlations between the Goal and Task sub-scales were greater than the correlations between Bond and Goal and between Bond and Task, possibly because Goal and Task form part of a technical dimension whereas Bond is a relational dimension characterized by the affective quality of the alliance. The high correlations found between the subscales of the WAI-P and WAI-T were similar to those reported by Horvath (1981) in his development study of the WAI and other studies using these original versions of the WAI. Undoubtedly, future research will examine correlations between the subscales of the Spanish-language WAI-P and WAI-T and analyze their factorial structure to determine whether these measures truly differentiate among the three components of alliance.

The convergent validity of the Spanish-language WAI-P and WAI-T was excellent. This convergence arose because the WAI and HAq-II both measure alliance and are related to a certain extent. In fact, the developers of the HAq-II (Luborsky et al., 1996) report that this measure contains 14 items (out of a maximum of 19) that evaluate different aspects of the alliance proposed by Bordin (1979) and Luborsky (1976). Our findings regarding convergent validity are in accordance with previously reported correlations between the English-language versions of WAI and other alliance measures (although Horvath [1981] did not use an independent measure of alliance in his work on developing the WAI).

There were some shortcomings in the discriminant validity of the Spanish-language WAI-P and WAI-T, as the correlations between the WAI-P or WAI-T and two independent measures of empathy (the EUS-P and EUS-T) were high. This is because alliance and empathy are related variables. It is difficult to imagine building and maintaining a consistent patient-therapist alliance in a manner independent of the level of empathy shown (or perceived by the patient to be shown) by the therapist. In the development study of the English-language WAI (Horvath, 1981), the correlations between the subscales of the WAI-P and the EUS-P, and between the subscales of the WAI-T and the EUS-T, were also high, although the majority were lower than those found here. We believe that the discriminative capacity of the Spanish-language WAI-P and WAI-T will improve when these measures are correlated with measures other than empathy that are less closely related to alliance.

Our results show that the Spanish-language WAI-P and WAI-T have good predictive validity. In other words, the higher the alliance scores in both Spanish-language measures after the third psychotherapy session, the greater the change undergone by patients after the tenth session. In particular, the overall WAI-P and the Task subscale of the WAI-T explain a moderate percentage of the variance in the change in the BDI. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first evidence for the usefulness of these two alliance measures in Spanish. However, correlations between the Spanish-language WAI and change in the BDI indicate covariance between these variables, not a causal relationship; therefore, these results should be interpreted with caution. Nor should it be inferred that the change undergone by the patients was due to the alliance established after the third psychotherapy session. Nevertheless, our results showing the predictive validity of the Spanish-language versions of the WAI-P and WAI-T are comparable to those of Horvath (1981) and subsequent studies using these original versions of the WAI in psychotherapy involving different approaches and different time frames (Horvath et al., 2011).

Our study has some limitations. First, the use of a relatively small patient and therapist sample (which is similar to that used in the development study of the WAI) reduces statistical power and makes it difficult to generalize from the results. In terms of construct validity, the small sample size prevented us from conducting a factorial analysis to extract the underlying dimensions of the two versions of the Spanish-language WAI. Second, the patient sample (which was comprised mostly of women) presented only depressive disorders, making it difficult to generalize our findings to other patients with whom a working alliance must be built and maintained. Third, there are limitations related to the predictive validity of the Spanish-language WAI-P and WAI-T: we cannot guarantee that changes in BDI scores were only the result of psychotherapy, and we were unable to compute correlations between the alliance and the change in the BDI for those patients who did not continue beyond the third session. Finally, it is possible that the correlations for the predictive validity of the WAI-P are somewhat inflated due to our use of the same source of information (the patients) about alliance and the results of psychotherapy. However, Horvath's (1981) initial study as well as numerous later studies (Horvath et al., 2011) used patient self-reports to measure both alliance and the results of psychotherapy.

Our Spanish adaptation of the long version of the WAI for patients and therapists takes it place alongside the work of other Spanish-speaking researchers with an interest in this well-known alliance measure. This includes the work of Corbella, Botella, Gomez, Herrero, & Pacheco (2011), who tested the factorial validity of a version of the WAI-Short for patients, and Waizmann and Roussos (2011), whose pilot study conducted in Argentina sought to adapt the WAI for observers (WAI-O).

In conclusion, the results obtained using the two Spanish-language versions of the WAI were satisfactory and consistent with those reported for the English-language versions. Future studies should focus on the psychometric properties of the Spanish measures (particularly their factorial validity). The possibility of using these tools in clinical practice and in training new professionals (i.e., in supervised tasks and structured training programs for alliance-building skills) should be considered.

Acknowledgements

This study was possible thanks to the participation of patients and therapists from several Spanish public health centers. We thank Professor Adam O. Horvath of Simon Fraser University (Canada) for providing the original versions of the WAI-P and WAI-T; Dr. Maria Sancho-Pascual, Dr. Zaida Nuhez-Bayo, and Dr. Mita Valvassori, linguists from the University of AlcaM's School of Writing (Spain), for their assistance; and Jesus P. Izquierdo-Garcia and Tania Iglesias-Cabo, mathematicians from the Statistical Consultancy Unit at the University of Oviedo (Spain), for their assistance. We also thank biologist Lourdes Fernandez-Casas for her unconditional, selfless, and resolute help carrying out this research.

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. (2002). Manual diagnóstico y estadístico de los trastornos mentales (Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders) (4.a ed., text rev.). Barcelona, Spain: Masson. [ Links ]

2. Andrade-González, N. (2005). La alianza terapéutica (The therapeutic alliance). Clinicay Salud, 16, 9-29. [ Links ]

3. Andrade-González, N. (2009, April). El papel del terapeuta en la alianza terapéutica (The role of the therapist in the therapeutic alliance). Paper presented at UNED, Guadalajara, Spain. [ Links ]

4. Barrett-Lennard, G. T. (1978). The Relationship Inventory: Later developments and adaptations. JSAS: Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology, 8(68), 1-55. [ Links ]

5. Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive therapy of depression. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

6. Beck, A. T., & Steer, R. A. (1993). Beck Depression Inventory: Manual. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation. [ Links ]

7. Bordin, E. S. (1979). The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 16, 252-260. [ Links ]

8. Bordin, E. S. (1994). Theory and research on the therapeutic working alliance: New directions. In A. O. Horvath & L. S. Greenberg (Eds.), The working alliance: Theory, research and practice (pp. 13-37). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

9. Corbella, S., Botella, L., Gómez, A. M., Herrero, O., & Pacheco, M. (2011). Características psicométricas de la versión española del Working Alliance Inventory-Short (WAI-S) (Psychometric properties of Spanish version of Working Alliance Inventory-Short (WAI-S)). Anales de Psicología, 27, 298-301. [ Links ]

10. Hanson, W. E., Curry, K. T., & Bandalos, D. L. (2002). Reliability generalization of Working Alliance Inventory scale scores. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 62, 659-673. Doi:10.1177/0013164402062004008. [ Links ]

11. Hill, C. E., & Lambert, M. J. (2004). Methodological issues in studying psychotherapy processes and outcomes. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin & Garfield's handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (5th ed., pp. 84-135). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

12. Horvath, A. O. (1981). An exploratory study of the working alliance: Its measurement and relationship to therapy outcome (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada. [ Links ]

13. Horvath, A. O., & Greenberg, L. S. (1986). The development of the Working Alliance Inventory. In L. S. Greenberg & W. M. Pinsof (Eds.), The psychotherapeutic process: A research handbook (pp. 529-556). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

14. Horvath, A. O., & Greenberg, L. S. (1989). Development and validation of the Working Alliance Inventory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 36, 223-233. [ Links ]

15. Horvath, A. O. (1994). Empirical validation of Bordin's pantheoretical model of the alliance: The Working Alliance Inventory perspective. In A. O. Horvath & L. S. Greenberg (Eds.), The working alliance: Theory, research and practice (pp. 109-128). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. [ Links ]

16. Horvath, A. O., Del Re, A. C., Flückiger, C., & Symonds, D. (2011). Alliance in individual psychotherapy. In J. C. Norcross (Ed.), Psychotherapy relationships that work: Evidence-based responsiveness (pp. 25-69). New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

17. LaCrosse, M. B. (1980). Perceived counselor social influence and counseling outcomes: Validity of the Counselor Rating Form. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 27, 320-327. [ Links ]

18. LaCrosse, M. B., & Barak, A. (1976). Differential perception of counselor behavior. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 23, 170-172. [ Links ]

19. Luborsky, L. (1976). Helping alliances in psychotherapy: The groundwork for a study of their relationship to its outcome. In J. L. Claghorn (Ed.), Successful psychotherapy (pp. 92-116). New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel. [ Links ]

20. Luborsky, L., Barber, J. P., Siqueland, L., Johnson, S., Najavits, L. M., Frank, A., & Daley, D. (1996). The Revised Helping Alliance Questionnaire (HAq-II): Psychometric properties. The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, 5, 260-271. [ Links ]

21. Muñiz, J. (2005). Utilizacion de los tests (Use of tests). In J. Muñiz, A. M. Fidalgo, E. García-Cueto, R. Martínez, & R. Moreno, Análisis de los ítems (Item Analysis) (pp. 133-172). Madrid, Spain: La Muralla. [ Links ]

22. Safran, J. D., & Muran, J. C. (2000). Negotiating the therapeutic alliance: A relational treatment guide. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [ Links ]

23. Sanz, J., & Vázquez, C. (1998). Fiabilidad, validez y datos normativos del Inventario para la Depresion de Beck (Reliability, validity, and normative data of the Beck Depression Inventory). Psicothema, 10, 303-318. [ Links ]

24. Tryon, G. S., Blackwell, S. C., & Hammel, E. F. (2008). The magnitude of client and therapist working alliance ratings. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training 45, 546-551. Doi:10.1037/a0014338. [ Links ]

25. Vázquez, C., & Sanz, J. (1997). Fiabilidad y valores normativos de la versión española del Inventario para la Depresión de Beck de 1978 (Reliability and normative data of the Spanish version of 1978 Beck's Depression Inventory). Clínica y Salud, 8, 403-422. [ Links ]

26. Vázquez, C., & Sanz, J. (1999). Fiabilidad y validez de la versión española del Inventario para la Depresión de Beck de 1978 en pacientes con trastornos psicológicos (Reliability and validity of the Spanish version of Beck's Depression Inventory (1978) in patients with psychological disorders). Clínica y Salud, 10, 59-81. [ Links ]

27. Waizmann, V., & Roussos, A. (2011). Adaptación del Inventario de Alianza de Trabajo en su versión observador: WAI-O-A (Adaptation of the Working Alliance Inventory in its Observer Form: WAI-O-A). Anuario de Investigaciones, 18, 95-104. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Nelson Andrade-González

Universidad de Alcalá

Facultad de Medicina y Ciencias de la Salud

Grupo de Investigación en Procesos Relacionales

y Psicoterapia

Campus Universitario

Carretera Madrid-Barcelona Km. 33,600

28871, Alcalá de Henares (Madrid, España).

E-mail: nelson.andrade@edu.uah.es

Article received: 30-06-2013

Revised: 25-09-2013

Accepted: 20-01-2014