Introduction

The construction of attachment in early childhood and its evolution into adulthood

Attachment is the capacity that leads people to build and maintain emotional bonds with other human beings throughout their lives (Hazan & Shaver, 1987). The main functions of attachment are the search for security and protection, provided by primary caregivers in early childhood, and later by interpersonal relationships -such as the sentimental partner- in adulthood (Dykas & Cassidy, 2011; Manning et al., 2017).

According to Bowlby's attachment theory (1979), people who have received a space of protection and assistance in times of threat or harm from their primary caregivers, and a base on which to lean and explore the world, form a type of secure attachment (Oliva-Delgado, 2004). People with secure attachment develop a mental model of trust in their environment, and a positive appreciation of themselves and others (Pinedo-Palacios & Santelices-Álvarez, 2006). However, people who had caregivers who were absent or with inconsistent responses in childhood develop an insecure attachment, characterized by negative mental models of themselves and distrust towards others (Kivlighan et al., 2017).

In adulthood, attachment style is defined through two dimensions: anxiety and avoidance (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). Anxiety is the degree to which a person worries because his or her attachment figures are not available in times of need, is afraid of being abandoned, deceived, or not being enough for others (Drake, 2014). Avoidance is the extent to which a person mistrusts others, and therefore prefers to maintain behavioral independence and emotional distance, avoiding intimacy in their relationships (Mili & Raakhee, 2015).

Adults with a secure attachment style have low anxiety and low avoidance, comfort with closeness and interdependence, confidence in seeking support, and cope with stress constructively (Mikulincer et al., 2003). They also present a high level of positive affect and are able to recognize and express emotions easily (van Rosmalen et al., 2016).

Adults with insecure attachment styles may be either anxious or avoidant (Brennan et al., 1998). Those with insecure anxious attachment have high levels of anxiety and low avoidance, a strong need for closeness, concerns about relationships, and a remarkable fear of rejection (Kerr et al., 2003). The predominant emotional state is worry and fear of separation, and a low tolerance of suffering (Shaver & Mikulincer, 2007). This insecure anxious attachment style is associated with higher levels of negative affect (e. g. hostility, sadness, guilt, fear, and nervousness) and lower levels of positive affect (e. g. calm and serenity) (Drake et al., 2011). Those with insecure avoidant attachment have high levels of avoidance and low levels of anxiety, which translates into a preference for emotional distance from others and a strong need for self-sufficiency (Andriopoulos, & Kafetsios, 2015). A characteristic of the high avoidance style is minimization of affect: although they present episodes of high levels of hostility, they tend to hide their anger by denying their emotion or presenting themselves as positive (Kivlighan et al., 2017).

In short, each individual's way of bonding is a consequence of the mental relationship models constructed in their affective experiences and tends to remain during the different stages of the life cycle (Hazan & Shaver, 1987; Howard & Steele, 2018).

The relationship between attachment and emotion regulation

Emotion regulation is the process by which a person exerts an influence on how they experience and how they express their emotions (Gross & John, 2003). This capacity for emotional management enables flexibility in emotional reactions in order to be able to respond adaptively to the demands of the environment (Gross, 2015). Certain individual differences in temperament, such as the ability to calm oneself, influence the development of emotion regulation (Séguin & MacDonald, 2018).

Temperament is the way in which the individual interacts with his or her surroundings, including the intensity and speed of the activation of their emotions before an event, and the ease and speed of return to the emotional baseline when it ends (Blair et al., 2004). This temperamental disposition has a biological or genetic component, but it is also influenced by the environment and life experiences with others (van Wijk et al., 2019). In specific terms, babies begin to regulate their emotions through social referencing with their first primary caregiver, and this link impacts on both biological and psychological development (Sarısoy, 2017).

Attachment is conceived in early childhood as the dyadic regulation of emotion, which in a secure attachment bond will impact the quality of the child's expression, modulation, and emotional flexibility (Sroufe, 2000; Tobin et al., 2007). Securely attached children openly express their emotions, manifest high levels of curiosity and exploration for novel stimuli, while modulating their level of arousal in the face of intense stimulation, more easily adjust the expression of their impulses to the context, and turn to an adult when their own capacities fail (Altan-Atalay, 2019; Kerr et al., 2003). Meanwhile, children with anxious attachment tend to experience difficulties when faced with emotional challenges in their relationships with peers, and present higher levels of discomfort and stress when they are deprived of parental attention, while those with avoidant attachment tend to use distracting strategies in stressful situations (Altan-Atalay, 2019; Diener, Mangelsdorf, McHale, & Frosch, 2002).

In adulthood, differences persist in the way emotions are regulated according to the style of attachment (Shaver & Mikulincer, 2007). People with a secure style are more comfortable when seeking emotional and instrumental support and tend to rely on others (Garrido-Rojas, 2006). They find it easier to experience, express and manifest their emotions, and do not become immersed in worries and negative memories (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2013). They seek support when under stress, and regulate their emotions in constructive ways, feel comfortable exploring new stimuli, are less hostile and more empathetic (Manning et al., 2017; Marganska et al., 2013).

Among people with an insecure attachment style, on the one hand, those with high levels of anxiety are hypervigilant to stress, and when regulating their emotions, they react by hyperactivating their proximity-seeking strategies (Mikulincer & Florian, 2003). They have a limited capacity to regulate negative emotional events, which is compatible with the state of worry in which they frequently find themselves (Ben-Naim et al., 2013). People with high avoidance have limitations in recognizing stress (Andriopoulos & Kafetsios, 2015). They use emotional deactivation as a regulatory strategy, defending themselves from stress, excluding painful thoughts and memories from their consciousness (Kivlighan et al., 2017).

Emotion regulation in adulthood is also positively related to other variables such as mental health (Skoyen et al., 2013), happiness (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2013) and job performance (Ronen & Zuroff, 2017).

The influence of attachment and emotion regulation on subjective well-being

Subjective well-being is defined as the sense of vitality, interest and positive mood, and is assessed through the individual's subjective assessment of his satisfaction with his life and affective well-being (Diener et al., 2010; Jovanović, 2015). It includes affective, physical, cognitive, spiritual, social and individual processes (Joshanloo, 2018). Adequate emotion regulation in youth is positively related to subjective well-being (Lavy & Littman-Ovadia, 2011; Stevenson et al., 2018).

Secure attachment is a determining factor for psychological health and for well-being (Kafetsios & Sideridis, 2006; Wei et al., 2011; Marrero-Quevedo et al., 2018). Conversely, high anxiety and avoidance in attachment are associated with lower levels of well-being and satisfaction with life (La Guardia et al., 2000; Lavy & Littman-Ovadia, 2011), as well as fewer positive emotions and more negative emotions in relationships (Ben-Naim et al., 2013; Stevenson et al., 2018).

Karreman and Vingerhoets (2012) noted that emotion regulation acts as a mediator between attachment style and well-being. Other studies suggest emotion regulation as a mediating variable between attachment and other factors, such as social anxiety (Nielsen et al., 2017) or empathy (Troyer & Greitemeyer, 2018). However, no literature has been found on the mediating role of emotion regulation between attachment and well-being specifically in youth, nor in the Spanish population.

The importance of well-being in young people

Youth is considered an important stage for the study of attachment, emotion regulation and well-being, as it is a transitional period during which people begin to develop adult roles, such as finding a romantic partner or stable employment (Arnett, 2007). Young Spaniards are a population especially susceptible to stress, given current working and social conditions (Ortega, 2013). Naturally, difficulties arise in learning the new skills and competencies required at this stage, which in addition to the complications arising from a complex historical, social and economic context, could lead young people to lower levels of well-being, to develop depressive and/or anxious symptoms and suffer relationship difficulties (Cantazaro & Wei, 2010; Rivera et al., 2011). This could have relevant repercussions for society at an economic and health level, as it is a public health problem (Domino et al., 2009; Joshanloo, 2018).

Aims of this study

The aim of this paper is to study the relationship between attachment and subjective well-being among a sample of young Spaniards, considering the mediating role of emotion regulation. Based on previous studies (e.g. Karreman & Vingerhoets, 2012; Stevenson et al., 2018; Troyer & Greitemeyer, 2018), we propose the following hypotheses: (I) anxiety and avoidance in attachment will be negatively related to emotion regulation and well-being; (II) emotion regulation will be positively related to well-being; and (III) emotion regulation will mediate the relationship between anxiety and well-being on the one hand; and between avoidance and well-being on the other.

Method

Participants

126 Spanish young people aged between 19 and 36 years old participated in the study (M Age = 24.16; SD Age = 3.54), of which 61.9% were women. 69.84% of the sample currently had a romantic partner. 84.92% identified themselves as heterosexual, 5.55% as homosexual, and 9.52% as bisexual.

Instruments

The Experiences in Close Relationship questionnaire (ECR-S; Brennan, Clark, & Shaver, 1998; validated version in Spanish by Alonso-Arbiol, Balluerka, and Shaver (2007) was used to measure attachment. This instrument consists of 36 items with a scale of seven response alternatives (1 = Totally disagree; 7 = Totally agree). It evaluates two dimensions of attachment: anxiety and avoidance. Reliability is high among our sample, with α = .88 for the avoidance scale and α = .92 for the anxiety scale.

The Spanish Trait Meta-Mood Scale (TMMS-24; Fernández-Berrocal et al., 2004) was used for evaluating emotion regulation. This instrument measures emotional intelligence and consists of 24 items on a scale with five alternative responses (1 = No agreement; 5 = Totally agree). It evaluates three factors of emotional intelligence: attention, clarity and repair. Only the repair scale, aimed at evaluating the person's beliefs about his or her own ability to regulate his or her feelings, was used in this study. The reliability of this scale for our sample is high (α = .83).

Subjective well-being was assessed using the variables of life satisfaction and affective well-being (Diener, 2000). On the one hand, the Satisfaction With Life Scale was used (SWLS; Diener et al., 1985; validated version in Spanish by Atienza et al., 2000). This brief scale assesses people's satisfaction with their living conditions. It consists of 5 items, with a scale of seven alternative answers (1 = Completely disagree; 7 = Completely agree). The scale has good reliability in our sample (α = .86). The Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE; Diener et al., 2010) was used to measure affective well-being. This scale consists of 12 items, with 6 referring to positive experiences and 6 to negative or worrying experiences. Participants are asked to rate the frequency they have experienced positive and negative feelings during the past month on a scale of five alternative responses (1 = Never; 5 = Always). It has two dimensions: positive affect and negative affect, and a global scale of overall affective well-being which is a balance of the other two. The scale presents acceptable psychometric properties in our sample (α = .70 for the positive affect scale and α = .74 for the negative affect scale).

Procedure

The participants' data were collected using the instruments described above, in accordance with the principles of the ethical standards of the World Medical Association's Declaration of Helsinki (2013). The confidentiality and anonymity of the data was maintained by using a research participation code that was not identifiable with the subject's personal data. The data were then entered and statistically analyzed.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using the statistical package SPSS (version 24.0) and PROCESS (Hayes, 2013). PROCESS is a tool that integrates various previously published statistical functions for the execution of mediation and moderation analysis. Correlation analysis between the variables was carried out, and four mediation models were tested in this study. Two mediation models performed with PROCESS (model number 4), bootstrapping for indirect effects was determined at 10.000, and the confidence level for confidence intervals at 95%. The estimation for the confidence intervals was performed using the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) and Maximum Likelihood (ML) methods. The total effects of the mediation model were also calculated.

Results

Bivariate correlations

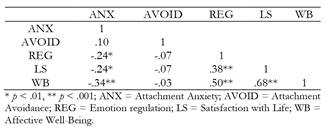

The correlational analyses (Table 1) showed that life satisfaction and well-being are strongly correlated (r = .68; p = .000). Emotion regulation correlates positively with life satisfaction (r = .38; p = .000) and affective well-being (r = .50; p = .000).

The anxiety dimension of attachment correlates negatively with emotion regulation (r = -.24; p = .008), satisfaction with life (r = -.24; p = .006) and affective well-being (r = -.34; p = .000). The dimension of avoidance does not correlate with any of the variables studied.

Mediation models

Two mediation models were carried out: in model A, the dependent variable was life satisfaction, and in model B, affective well-being. The independent variable was attachment anxiety, and the mediating variable was emotion regulation in both models. The mediation models were not performed with avoidance as an independent variable, since in the correlation analysis we observed that avoidance is not significantly related to emotion regulation, or to subjective well-being.

As observed in model A (Figure 1), attachment anxiety explains emotion regulation (B = -1.22; t = 19.69; p = .008; SE = .45; LLCI = -2.11; ULCI = -.33), and emotion regulation explains life satisfaction (B = 0.33; t = 4.00; p = .000; SE = .08; LLCI = .17; ULCI = .50). As the total effect shows, attachment anxiety explains life satisfaction on its own (B = -1.22; t = -2.78; p = .006; SE = .44; LLCI = -2.09; ULCI = -.35). As the direct effect indicates, when emotion regulation is introduced, this relationship ceases to be significant (B = -0.82; t = -1.91; p = .058; SE = .47; LLCI = -1.66; ULCI = .03). This mediation model explains 16.72% (R 2 = .1672) of the variance of life satisfaction.

Figure 1. Model A.* p < .05, ** p < .001. TE= Total Effect. DE= Direct Effect. R 2 = .1672; F = 12.35; p = .000; Indirect Effect = -.40; SE = .21; BootLLCI = -0.90; BootULCI = -0.07.

As shown in model B (Figure 2), attachment anxiety explains emotion regulation (B = -1.22; t = -2.71; p = .008; SE = .45; LLCI = -2.11; ULCI = -.33), and emotion regulation explains affective well-being (B = 0.56; t = 5.76; p = .000; SE = .10; LLCI = .37; ULCI = .75). As the total effect shows, attachment anxiety explains affective well-being on its own (B = -2.16; t = -3.96; p = .000; SE = .55; LLCI = -3.23; ULCI = -1.08). As the direct effect indicates, when emotion regulation is introduced, the relationship remains significant (B = -1.48; t = -2.95; p = .004; SE = .50; LLCI = -2.47; ULCI = -.49). This mediation model explains 30.16% (R 2 = .3016) of the variance of affective well-being.

Figure 2. Model B. * p < .05, ** p < .001. TE= Total Effect. DE= Direct Effect. R 2 = .3016; F = 26.56; p = .000; Indirect Effect = -.68; SE = .31; BootLLCI = -1.40; BootULCI = -.14.

In short, our results show that emotion regulation mediates the relationship between anxiety and subjective well-being.

Discussion

Emotion regulation is the process by which a person exerts an influence on how they experience and express their emotions (Gross & John, 2003). There are differences in the way emotions are regulated according to each person's style of attachment (Garrido-Rojas, 2006; Kivlighan et al., 2017; Manning et al., 2017), which in turn influences their level of subjective well-being (Lavy & Littman-Ovadia, 2011; Stevenson et al., 2018).

Previous studies suggest that emotion regulation may be mediating the relationship between attachment style and subjective well-being, which explains the relationship between these two variables (Nielsen et al., 2017). Youth is an stage in development when people begin to develop the skills and competencies of adulthood, and a time when they are particularly susceptible to increased stress and reduced well-being (Cantazaro & Wei, 2010; Rivera et al., 2011). As a result, the objective of this work was to study the relationship between anxiety and avoidance of attachment with subjective well-being in young Spanish adults, considering the mediating role of emotion regulation.

Our first hypothesis suggested that anxiety and attachment avoidance will be negatively related to emotion regulation and well-being (Ben-Naim et al., 2013; Marrero-Quevedo et al., 2018). The results are partially consistent with this hypothesis: this relationship occurs in the case of anxiety, but not in the case of avoidance. This means that people with greater attachment anxiety, who are more concerned about their attachment bonds and suffer greater fear of being abandoned or deceived, also have more difficulty regulating their emotions, and report significantly lower levels of subjective well-being (Garrido-Rojas, 2006; Manning et al., 2017). However, people with a greater tendency to avoidance, who prefer to establish a low level of intimacy in their relationships and maintain emotional distance, do not seem to have poorer emotion regulation, and nor do they report lower levels of subjective well-being.

The absence of relationship between avoidance and the other variables in our study (emotion regulation and subjective well-being), could be explained by several reasons. One possibility is that since these are self-report questionnaires ─ which evaluate the subjective perception of skill ─ avoidant people overestimate their ability to regulate their emotions, as a consequence of their poor awareness of their emotional world (Kafetsios & Sideridis, 2006; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2007). Another possibility is related to the emotion regulation strategy most used by avoidant people: the deactivation of emotions. They could therefore report a high level of affective well-being, because one of their usual mechanisms is to defend themselves from stress by excluding painful emotions, thoughts, and memories from their consciousness (Andriopoulos & Kafetsios, 2015).

In our second hypothesis, we stated that emotion regulation will be positively related to subjective well-being: the results are consistent with this hypothesis. People who have greater capacity to manage their emotions and behaviours have a greater tendency to present higher levels of satisfaction with life, and to report more positive emotions and pleasant experiences (Lavy & Littman-Ovadia, 2011; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2013).

The results suggest the partial confirmation of our third hypothesis, which suggested that emotion regulation will be mediating the relationship between anxiety/avoidance and well-being. This mediation takes place in the case of attachment anxiety, but it does not occur in the case of attachment avoidance. Specifically, attachment anxiety does not appear to directly influence satisfaction with life, but it does have an influence through the mediation of emotion regulation. People with high levels of anxiety have poorer strategies for regulate their emotions, which could lead to lower levels of satisfaction with their lives. Attachment anxiety also negatively affects a person's ability to deal with negative experiences, both directly and because of difficulties in managing their emotional states. The results obtained are consistent with the findings of Karreman and Vingerhoets (2012).

This study is not free of limitations. One of these is that, although the instrument used to measure emotional ability (Fernández-Berrocal et al., 2004) is one of the most widely validated in the Spanish-speaking population (Valdivia-Vázquez et al., 2015), it is a self-report instrument that evaluates the perception of competence, and not competence itself. It would be interesting to replicate the results using other measures of emotion regulation, with either more specific instruments for measuring this construct, or through tasks of execution aptitude.

For future research along this line, we propose to expand the study sample to confirm whether the results obtained are maintained in different populations. It would also be interesting to check the causality of our results in a longitudinal study. Based on the findings of this research, we emphasize the interest of developing psychoeducational programs for learning strategies for emotion regulation, as a way to increase the life satisfaction and affective well-being of young people with anxious attachment tendencies. We believe that young people with avoidant attachment tendencies are more likely to benefit from interventions focused on increasing perception, labeling, and understanding of emotions than from interventions focused on regulation (Andriopoulos & Kafetsios, 2015).

Why do we need to invest resources in promoting young people's well-being? First, youth is a crucial period when people are especially susceptible to stress, as they begin to feel the demands of adult roles very strongly (Arnett, 2007). Second, young people are a sector of the population that have suffered particularly as a result of Spain's socio-economic situation (Ortega, 2013). If we also take into account the close relationship between well-being levels and mental health and social adjustment (Mikulincer & Florian, 2003), the social need in our country to invest resources in promoting young people well-being is evident (Domino et al., 2009). By enhancing the vitality, interest and positive mood of the youngest sector of society by appropriate emotional education, we could have a physically and mentally healthier population, better prepared for work and for relationships with others, and for establishing secure families in the future (Jovanović, 2015; Ronen & Zuroff, 2017; Skoyen et al., 2013).

texto en

texto en