Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

The European Journal of Psychiatry

versión impresa ISSN 0213-6163

Eur. J. Psychiat. vol.24 no.3 Zaragoza jul./sep. 2010

Gender differences in incipient psychosis

Ana Barajas*,**; Iris Baños**; Susana Ochoa**; Judith Usall**; Elena Huerta**; Montserrat Dolz***; Bernardo Sánchez***; Victoria Villalta**; Alexandrina Foix**; Jordi Obiols****; Josep María Haro**; GRUPO GENIPE

* Department of Research. Centre de Higiene Mental Les Corts, Barcelona

** Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu, Sant Boi de Llobregat. Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM)

*** Hospital Sant Joan de Déu de Barcelona, Esplugues de Llobregat. Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM)

**** Psychopathology and Neuropsychology Research Unit, Department of Clinical and Health Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, Autonomous University of Barcelona, Bellaterra, Barcelona. SPAIN

This project received financial help from the Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias de España (FIS PI05/1115); from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III de España, Centro de Investigación en Red de Salud Mental (CIBERSAM) and from Caja Navarra.

ABSTRACT

Background and Objectives: To describe gender differences in a group of patients with first-episode psychotic in different aspects: socio-demographic features, characteristics of the phases prior to disease onset (premorbid and prodromic periods), clinical manifestation of psychotic symptoms and possible corresponding cognitive alterations after disease onset, using the age at onset of first psychotic episode as a control variable.

Methods: Longitudinal study of 53 consecutive cases with a first psychotic episode. Inclusion criteria: two or more psychotic symptoms; age between 7 to 65 years old; first consultation to the medical center of study; less than 6 months since the first contact to the medical service; and less than a year of symptoms´ evolution. The methodologic assessment includes: a socio-demographic questionnaire and an extensive battery of tests to assess premorbid/prodromic, clinical and cognitive characteristics. We perform mean differences tests to analyze continuous variables (non-parametric U-Mann-Whitney and t-Student test) and chi-square test for categorical variables (SPSS 16.0).

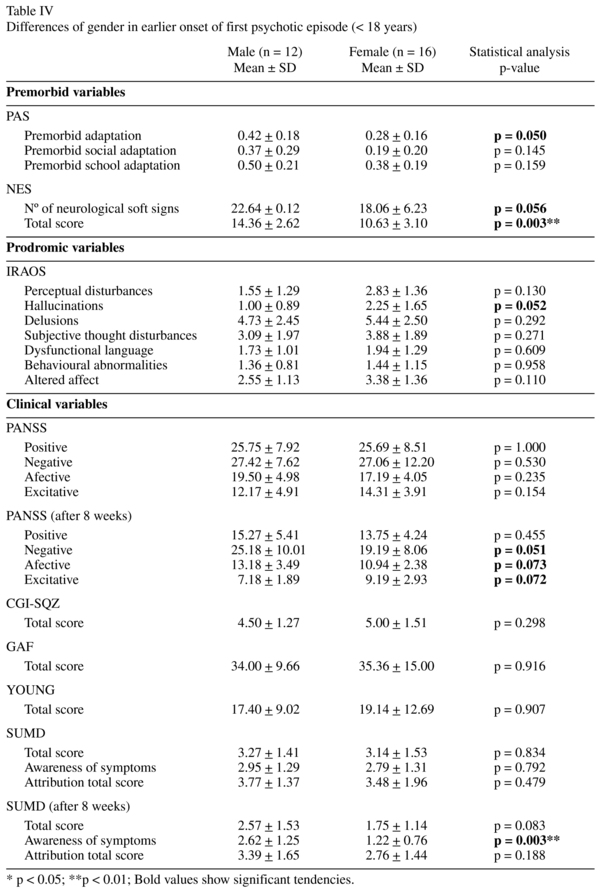

Results: In the group of patients under 18 years, men showed higher scores in adjustment premorbid (U = 54.0, p = 0.050), more neurological soft signs (U = 31.0 p = 0.003), more negative psychotic symptoms (U = 48.5, p = 0.051) and worse insight (U = 30.0, p = 0.003) than women (after 8 weeks of psychotic episode onset).

Conclusions: We found gender differences in most of the variables analyzed when age at onset was controlled. These differences should be taken into account to learn more about the different types of onset of the disease, its prevention and possible improvements in therapeutic approach. Our findings suggest that younger men with an earlier onset of psychotic episode have more alterations in the stages prior to the onset of the disease supporting the neurodevelopmental hypothesis for gender differences.

Key words: First episode; Gender differences; Incipient psychosis; Neurodevelopmental; Age of onset.

Introduction

"...Gender differences are an ideal window through which to look at the interplay of biological and psychosocial factors"1.

The study of gender differences in the psychotic spectrum disorders has given rise to a number of models which have been grouped in two different dimensions: clinical/psychosocial and neurobiological2,3. The first refers to the expression of symptoms and social behaviour in schizophrenic patients. Males show a higher frequency of negative psychotic symptoms, whilst females, have a higher probability of showing affective symptoms4,5; usually, women with schizophrenia are more active and have a wider social network than affected men, who, in turn, are more passive and have social difficulties6,7. The neurobiological dimension could include four hypotheses regarding gender differences in schizophrenia: a) the estrogen hypothesis postulates a protective effect by estrogens in the development of schizophrenia in women which could explain certain gender differences in the manifestation of the disease8. In women, estrogens could retard schizophrenia development up to menopause, which would explain its late onset9; b) different sub-types of schizophrenia: postulates the existence of two distinct schizophrenias, masculine and feminine10, corresponding to different forms of expression of specific psychotic symptoms according to the gender of the patient rather than the existence two types of schizophrenic endophenotypes which are clearly differentiated. Castle et al.11, performed a study on a sample of patients with a first psychotic episode and identified three groups: a neurodevelopmental type (predominantly male), a schizoaffective type (almost entirely female) and a paranoid type (with equal sex ratio); c) early and late developmental models: both models postulate changes in the neurological development which predispose the appearance of schizophrenia, but in accordance with the early neurodevelopmental model, these anomalies start at the prenatal and neonatal stages12. On the other hand, the late neurodevelopmental model supports the hypothesis that these occur later in life, particularly during adolescence13; d) and brain lateralization: this model attributes gender differences in schizophrenia to the differential hemispheric organization of the male and female brain since the latter is more symmetrically organized (less lateralized) than the male brain14.

These models do not necessarily contradict each other since they explain distinct aspects and periods in the disease progression. Häfner et al.15,16, stated that the combination of both clinical/psychosocial and neurobiological models could explain gender differences in the expression of schizophrenia. Both clinicians and researchers have observed that males and females do not manifest psychotic spectrum disorders in the same way, since both differ in multiple aspects. In general, women tend to have a more benign form with less deterioration at presentation of schizophrenia.

Socio-demographic Variables

A consistent finding in the literature is the difference between men and women at age of onset of schizophrenia: males have an earlier age of onset compared to females by 3 - 5 years17,18, independently from the culture of the study group or the diagnostic classification used3. Castle et al.19, mention 3 peaks in the age at onset of schizophrenia with distinct distributions between women and men: an early peak which was more prominent in males, a middle peak which was more frequent in females and a third, late onset peak, which was nearly exclusively composed of females coinciding with the results from other studies17,18,20. Studies conducted on patients who presented a first psychotic episode21,22 continue to corroborate this idea. However, these results do not agree with other studies which do not found differences in age at onset between genders23,24.

Throughout the last decades, other socio-demographic variables and their relationship with gender have been taken into account to explain the observed variability in the manifestation of schizophrenia. Various studies have demonstrated that the age of women at primary hospitalization was higher than for men25, that the development of the disease in women was less severe26 and that premorbid competence was better in women than in men measured according to educational level, civil and work status27.

Studies by Mueser et al.28 and Rabino-witz et al.29 showed a lower frequency in alcohol, cannabis and other substance abuse in women than in men. In a study from Rabinowitz et al.29, in a sample of patients with a first psychotic episode, 17% of men and 6% of women had a moderate-severe grade of substance abuse.

Premorbid and prodromic variables

Classically, the premorbid period has been defined as the period preceding the start of clinical psychosis, whilst the prodromic period refers to the period in which the disease process starts in the absence of clear psychotic symptoms. Studies on the difference between genders during pre-psychotic periods have increased our knowledge regarding the variability in risk factors with respect to gender, the different characteristics in the transition process of psychosis and its later evolution and prognosis in both genders.

Numerous studies which have analyzed gender differences during the premorbid period in schizophrenic patients have shown a better premorbid adaptation in women than in men30-32, but their conclusions are not consistent33,34. Such differences could be explained by a higher probability in the presentation of altered patterns in neurodevelopment in men than in women35.

Häfner et al.9 explained that the better premorbid functioning (PF) in women with schizophrenia is due to social and academic factors: a later onset of the disease, an increased ability to maintain social relationships, to have finished their studies and to have an active life before the start of the first psychotic episode.

Studies in patients with a first psychotic episode have shown a possible relationship between the presence of Neurological Soft Signs (NSS) and the male gender36. NSS are minor ("soft") neurological abnormalities in sensory and motor performance identified by clinical examination. In a follow-up study by Madsen et al.36, a significant increase in the number of neurological abnormalities was observed in a group of males five years after the onset of the first psychotic episode. Nevertheless, results from studies with schizophrenia patients were not consistent with respect to the differences in gender and NSS. These studies showed increased NSS in patients with schizophrenia when compared to a healthy control group, however there is little evidence regarding gender differences with respect to the mean NSS demonstrated by patients37,38.

In a study by Häfner39, which analyzed prodromic symptoms in a patient sample with a first psychotic episode, no gender differences were observed in the ten most frequent initial symptoms, except in worrying, which was significantly more frequent in women. In a sample of 231 patients with a first psychotic episode, Gutiérrez et al.40 observed that the male group manifested the following prodromic symptoms with increased frequency: unusual perceptive experiences, deterioration in personal hygiene and psychosocial isolation. Nevertheless, due to difficulties in evaluating the prodromic period, as well as the variety of existing instruments, a number of inconsistencies in the methodology have been introduced in the scientific literature preventing a consensus in the study of prodromic symptoms.

Clinical Variables

The most reproducible data in the study of gender differences in the expression of psychotic symptoms has been the predominance of negative symptoms in men such as social withdrawal, blunted effect, poverty of speech and amotivation35,41-43. In contrast, studies have shown that women manifest more affective symptoms, atypical and cyclical forms of psychosis as well as a higher incidence in the diagnosis of paranoid and disorganized subtypes4,44,45. Szymanski et al.45 observed less illogical thinking but more anxiety, inappropriate affect and bizarre behaviour in women than men with first psychotic episode. Shtasel et al.46 showed that men with schizophrenia sho-wed more negative symptoms than women, however there were no gender differences with respect to positive psychotic symptoms. The studies of Gur et al.47 and Lindamer et al.48, both studies confirmed that women experience less negative symptoms than men and that this is more evident in women who develop the disease later in life. Nevertheless, there are studies which did not demonstrate psychopathological differences between men and women suffering from schizophrenia23,49,50.

Traditionally it was considered that wo-men with schizophrenia had better insight which in turn allowed them to use mental health services more than men. However, publications in the last years do not show any conclusive results regarding the relationship between gender and level of insight. On the other hand, a study with patients with a first psychotic episode, Mc Evoy et al.51 demonstrated that multiple factors exist which contribute to having a good insight including late onset of the psychotic episode and female gender whilst earlier studies52 go in the opposite direction and show that worse insight is associated with the female gender.

Cognitive function variables

Although a vast amount of work has been dedicated to study the cognitive function in schizophrenic patients, no consensus was reached with respect to gender differences. Some studies showed that men with schizophrenia have a greater cognitive deficit than women, especially in verbal processing; on the other hand; other studies conclude that women show worse cognitive function; whilst other studies failed to demonstrate any differences between the two groups.

Haas et al.42 did not show any gender differences in cognitive functioning in patients with first psychotic symptoms, however, in patients with disease progression of 5 years or more, men showed a greater deficit in verbal tasks, which could indicate dysfunction in the left hemisphere. Various studies indicated that men with schizophrenia have more alterations in sustained attention, abilities in language, executive functions and intelligence than women53,54. Nevertheless, other studies did not show any gender differences in cognitive functions between patients55,56. On the other hand, others have found major alterations in the female group with schizophrenia on attention and conceptualization tasks57 as well as on verbal me-mory, spatial memory and visual processing tasks58.

Aim

The aim of this study was to describe gender differences in a group of patients with first-episode psychotic in different aspects: socio-demographic features, characteristics of the phases prior to disease onset (premorbid and prodromic periods), clinical manifestation of psychotic symptoms and possible corresponding cognitive alterations after disease onset, using the age at onset of first psychotic episode as a control variable.

Methods

Sample

Our sample was composed of patients with a first psychotic episode selected in a consecutive manner. The patients were recruited when they were consulting in an adult mental health services at Sant Joan de Déu or the infant-juvenile services at the Hospital San Joan de Déu, either in a hospital or in a community psychiatric services. These centers belong to the metropolitan area and outskirts of Barcelona, taking into account a reference population of approximately 800,000 persons.

The inclusion criteria were: two or more psychotic symptoms (delirious ideas, hallucinations, disorganized speech, catatonic or disorganized behaviour and negative symptoms); age between 7 and 65 years; first psychiatric visit in any centre participating in the study; less than 6 months since the first contact to the medical service; and less than a year of symptoms' evolution. Patients diagnosed with mental retardation, craneo-encephalic trauma or dementia were excluded from the study.

All selected individuals were informed of the objectives and methodology of this study by their psychiatrist or researcher and signed the required informed consent. In cases where the patients were minors, the informed consent was obtained from their parents or carers.

The study was approved by the Ethics and Research Comittee of the "Sant Joan de Déu".

Instruments of measurement

The socio-demographic characteristics of the sample (gender, mental health centre (community psychiatric services/ hospital), race, socioeconomic status, marital status, ages and level of education, and work status) including age at onset of illness, initial visit at a psychiatry services, history of substance abuse and family psychiatry history, were obtained via a clinical-sociodemographic questionnaire.

Information about premorbid and prodromic variables was collected using the following scales or interviews:

Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS)59. A 26-items scale, administrated by an researcher, which evaluates sociability and withdrawal, social relationships, adaptation to school and behavior at school in four periods: childhood, up to 11 years; early adolescence, 12-15 years; late adolescence, 16-18 years; and adult life, above 18 years; as well as social-sexual aspects after 15 years of age. The PAS also includes a section composed of 9 general items related to education, work, performance at work or at school, behaviour at school immediately before onset of psychosis, elevated level of independence on the family, high levels of social-personal adjustment, grade of interests in life and energy level. The total PAS score were in the range of 0.0 and 1.0, wherein higher scores represented lower levels of FP. The premorbid adjustment scale was completed using all available data, including clinical history data, interviews with patients and relatives. The scale was translated and its used was validated in the Spanish population60.

The present study is based on the results obtained from the research of Norman et al.31 which find two factors: one showing academic PF (adaptation to and behaviour at school) and the second one showing a social PF (sociability and withdrawal; poor relationships and social-sexual adjustment).

Interview for the Retrospective Assessment of the Onset of Schizophrenia (IRAOS)61: Structured interview which evaluates retrospectively the start of schizophrenia. The interview is composed of 5 sections for the collection of socio-demographic data relating to the patient, psychiatric symptoms starting from 12 years of age, prodromic symptoms and establishment of the disease as well as the quality of the information. In the present study, only the section comprising prodromic symptoms was used. This included 7 parts: perceptual disturbances (excluding hallucinations); hallucinations; subjective thought disturbances (i.e. thoughts being read, thought insertion); delusional ideas and delusions; cognitive deterioration; altered affect; behavioural and motor abnormalities; and dysfunctional language. The presence or absence of such symptoms was evaluated.

Neurological Evaluation Scale (NES)37: a 26-item scale with three main subscales: sensory integration (SI), motor coordination (MC), sequencing of complex motor acts (SCMA) and an extra subscale that evaluates short-term memory, frontal release signs, and eye movement abnormalities ("others" subscale). Each item is rated from 0 to 2: 0 (no abnormality), 1 (mild, but definite impairment) and 2 (marked impairment). The higher the rating in total score, the higher the presence of neurological soft signs.

Information regarding clinical variables was obtained via the following scales or interviews:

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)62, translated and validated by Peralta and Cuesta63. This scale is the most widely used scale of psychotic symptom evaluation. It measures 30 symptoms on a scale of 1-7, with higher scores indicating higher psychopathology. In this study, in order to analyze the date we have used four dimensions described by Villalta et al.64: positive, negative, affective, and excitative.

At the moment of inclusion of the patient, a retrospective evaluation of the symptoms was carried out in those cases where the psychiatrist reported a previous more severe symptomatology. A second evaluation was carried out 8 weeks later since the onset of episode.

Clinical Global Impression- Schizophrenia scale (ICG-ESQ). Determine the severity of the disease (scale from 1 to 7, from normal to higher severity) and the grade of improvement (scale from 1 to 9, from major improvement to non applicable) in four groups of schizophrenia symptoms (positive, negative, cognitive and depressive). A global severity score of the disease is also determinaded. Its use has been validated for use in the spanish population with the same purpose as the present study65.

Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF)66 is used to measure global functioning (clinical/social), where 0 represents severe dysfunction and 100 represents good functioning.

Scale for the Assessment of Unawareness of Mental Disorder (SUMD)67: a 20-item scale which assesses awareness of mental disorder, awareness of response to medication, awareness of social consequences of mental disorder, and awareness of specific symptoms of the illness. These items are rated according to a scale of 1 to 5, where a score of 1 is considered as being aware, a score of 3 is somewhat aware, and a score of 5 is unaware. For each symptom presented, a score is calculated based on the attribuition which the patient gave to the symptom (1 = Correct: symptom is due to a mental disorder; 3 = Partial: unsure, but can consider possibility that it is due to a mental disorder; 5= Incorrect: symptom is unrelated to a mental disorder). Higher scores on this scale indicate poor awareness.

Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS)68: an 11-item scale which measures maniac symptoms. For adult patients the scale was administered by the researcher, whilst for adolescents, the self-administered version for parents (P-YMRS) was utilised. Some items were scored from 0-4 or 0-8 (in the case of items 5, 6, 8 and 9). The value of 0 means absence of symptoms whilst the highest value indicates the presence of the severe symptoms.

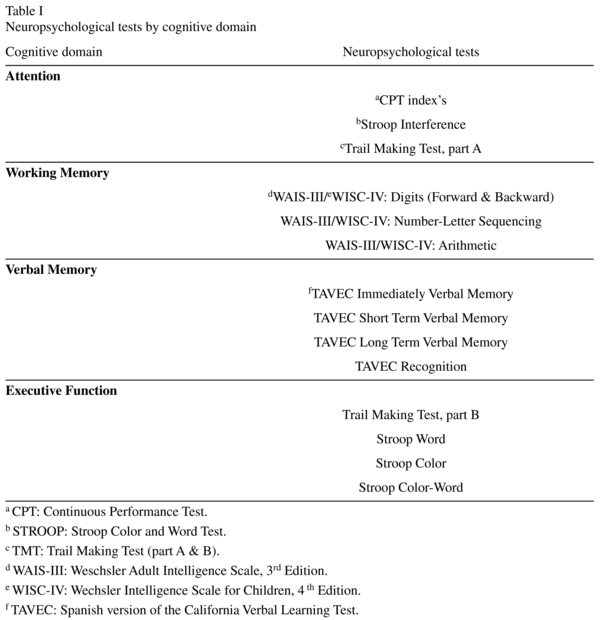

Cognitive assessment was performed by means of a neuropsychological battery designed to assess cognitive functions that the literature reports to be affected in psychotic disorders: attention, working memory, executive functioning and verbal memory. Table I summarises the neuropsychological tests which were used to measure each of these cognitive domains. To be able to calculate the total score for each of these domains, the direct score was transformed into a T-score (mean 50; SD = 10) and the mean of the scores according to each cognitive domain was calculated.

Statistical analysis

After verifying the hypothesis for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov non-parametric test (p < 0.05) for all variables of the study, the gender differences were analyzed for each group of variables of interest.

The socio-demographic variables of patients were analyzed using a chi-square test for categorical variables and Student's test for continuous variables. For comparison of categorical variables with expected frequencies cells less than 5, the Fisher's exact test was used.

For the analysis of premorbid and prodromic variables, differences of the means were calculated for independent samples (Student's T-test) which allowed comparison the scores of PAS, NES and IRAOS with respect to gender.

Gender differences in clinical and cognitive variables were analyzed using differences of the means (Student's T-test) since all variables were quantitative and complied with the criteria for normality.

For the whole variables (socio-demographic, premorbid/prodromic, clinical and cog-nitive), a second analysis was carried out taking into account the age at onset of the psychotic episode. For this part of the study, the sample was divided into adults (> = 18 years) and adolescents (<18 years). The data were analyzed using the non-parametric U-Mann-Whitney test.

Analyses were carried out using SPSS statistical software package (version 16.0). All statistical tests were two-tailed, with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Up to now, 53 patients with a first psychotic episode have been evaluated. Males compose 49.1% (n = 26) of the sample with a mean age of 20.21 years (SD = 6.2). Patients which started the psychotic episode at less than 18 years of age, comprise 52.8% (n = 28) of the sample with their mean age being 16.14 (SD = 1.2). The subgroup which had the first psychotic episode in adulthood had a mean age of 24.76 years (SD = 6.3).

Gender differences with respect to socio-demographic characteristics and substance abuse

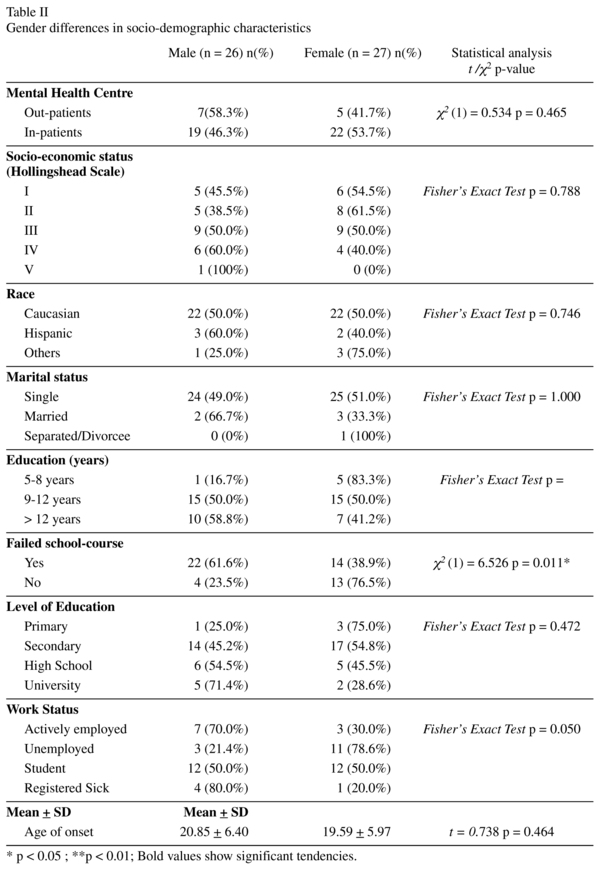

Table II shows the gender differences and socio-demographic variables of the sample used in this study. Analysis of these results revealed significant differences only in two of the socio-demographic variables: failed school-course (χ2(1)= 6.526, p = 0.011) and work status (Fisher's Exact Test= 7.702, 0 = 0.050).

Women comprise 76.5% (n = 13) of the sample which did not fail any school-course, whilst from the repeater group, 61.1% (n = 22) are men. With respect to work status, 70% (n = 7) of patients who worked before the onset of the psychotic episode were men and from the patients who were unemployed 78.6% (n = 11) were women.

No significant differences were observed between the groups of men and women with respect to the time elapsed until they had contact with mental health services (t = 0.650, p = 0.519), although the average number of days was higher in men and than in women (114 days against 89 days respectively).

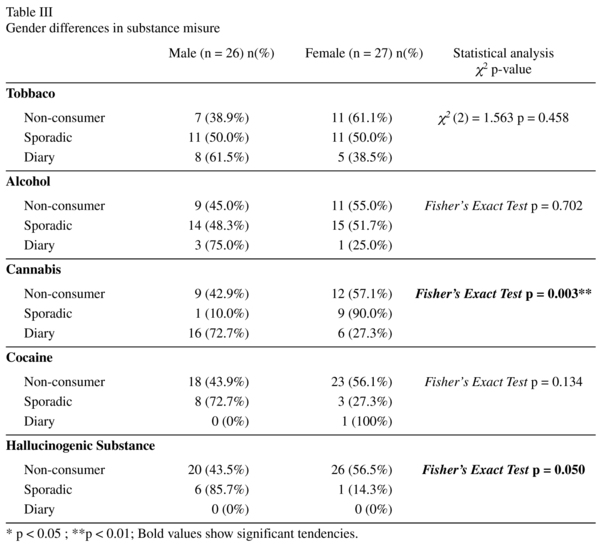

With respect to substance abuse, there were significant differences between the genders in the consumption of cannabis and hallucinogenic substances (Table III). Women composed 90% (n = 9) of sporadic consumers of cannabis, whilst 72.7% (n = 16) of daily consumers were men. In this sample there were no daily consumers of hallucinogenic substances, however 85.7% (n = 6) of sporadic consumers were men.

Patients belonging to families with previous psychotic disorders history comprise 28.3% (n = 13) of the sample, 17% (n = 9) of which are women. However, no significant differences were observed with respect to gender in family psychiatric history which includes disorders of the psychotic spectrum, affective disorders and others.

In a second analysis, no significant differences were observed between genders when the sample was divided into different age groups (<18 years: U = 88.0, p = 0.684; > = 18 years: U = 70.5, p = 0.720).

Gender difference in premorbid variables and prodromic symptoms

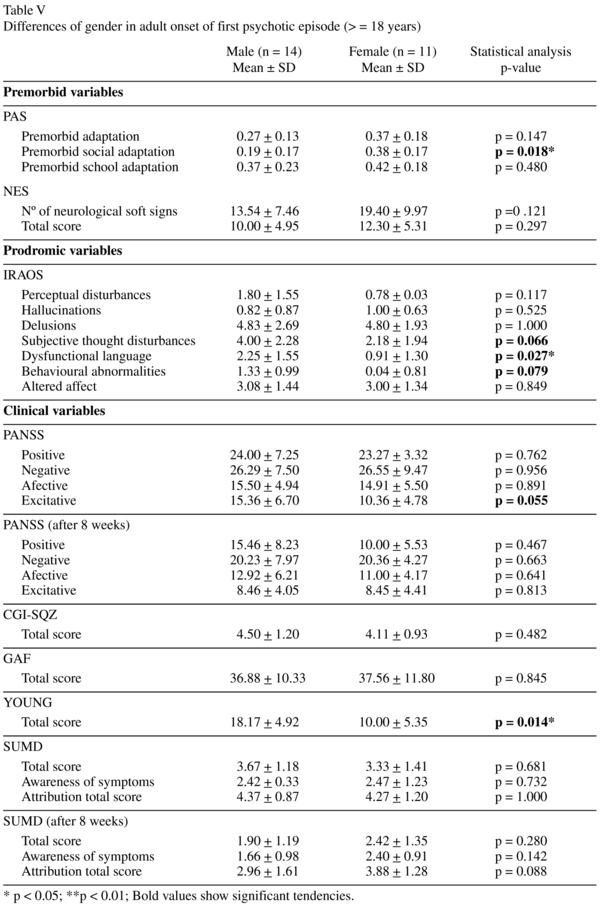

No significant gender differences were found in this sample either in global premorbid functioning or in its social and academic dimensions. However, when the effect of age at onset of psychotic episode was taken into account, significant differences were revealed: in patients younger than 18 years, men showed higher PF scores than women in total PAS (U = 54.0, p = 0.050) (Table IV). In patients older than or equal to 18 years of age, women showed the highest scores, although this happened only in the social domain (U = 29.5, p = 0.018) (Table V). In patients younger than 18 years, significant differences in PF during early adolescent stage was observed (U = 38.0, p = 0.013), with males showing lower scores.

No significant differences between genders were observed in the presence of minor neurological signs (t = 0.394, p = 0.695). When the effect of age at onset of psychotic episode was taken into account, significant gender differences were observed: in the group younger than 18 years of age, men show higher number of minor neurological signs (U = 31.0, p = 0.003) and also higher total NES scores (U = 47.0, p = 0.056) (Table IV) than women; in patients 18 years and over, no significant differences were observed with respect to gender.

Analysis of prodromic symptoms showed significant differences in gender in hallucinations, with a higher presence in women (t = -2.36, p = 0.017). When age at the beginning of psychotic episode was taken into account, this tendency was maintained in the age group younger than 18 years but not in the older group (> = 18 years) (U = 49.5, p = 0.052) (Tables IV y V). In this group there were significant differences in dysfunctional language (U = 31.0, p = 0.027) and tendencies in the variables for "subjective thought disturbance" (U = 33.0, p = 0.66) and "behavioural and motor abnormalities" (U = 39.0, p = 0.79) with higher scores obtained for males (Table V).

Gender differences in clinical variables

No significant gender differences were observed with respect to the presence and severity of psychotic symptoms at the onset of the psychotic episode. However, when age at onset was taken into account, gender differences were observed: men < 18 years showed an increased severity in negative psychotic symptoms with respect to wo-men, both in the acute phase (although significant differences were not observed: Xmales = 15.63; Xfemales = 13.66; p = 0.530) and during the stable phase, showing a significant tendency (U = 48.5, p = 0.051) (Table IV). In the > = 18 years age group, a tendency in gender differences with respect to excitative symptoms was observed in the acute phase with men showing a higher score (U = 42.0, p = 0.055). On the Young scale, significant gender differences were observed only in the group > = 18 years, with males showing higher scores than women (U = 34.0, p = 0.014) (Table V).

As other clinical variables, gender differences were observed if age at onset of the disease was taken into account, regarding to the awareness of the disease. In the group which started the episode at an earlier age, awareness of the symptoms of the disease was worse in males (U = 30.0, p = 0.003) (Table IV). On the other hand, in the older age group the opposite result was observed, with women scoring lower on the subscale for symptom awareness of SUMD, although this difference was not significant (U = 42.5, p = 0.088) (Table V). No significant differences between genders were observed in the attribution of symptoms.

No other significant differences were observed between genders in the other clinical variables studied (GAF and CGI).

Gender differences in cognitive functioning

In the analysis of cognitive domains, significant gender differences were observed only with respect to verbal memory (t = 2.49, p = 0.017) with worse scores obtained by women. These differences were still observed after subdividing the sample into age groups according to age at onset of first psychotic episode.

Discussion

Gender differences with respect to psychotic disorders are an important factor in the understanding of the manifestation and development of the disease. Even though in the last decades this was an intensively studied aspect, controversial results were obtained from the different studies performed.

In line with Angermeyer et al.27, we observed that women have a higher educational competence than men. On the other hand, our results do not coincide with these authors with respect to labour competence, with men being in a better situation before onset of the disease. In the last decades, several studies have been published supporting the hypothesis that no gender differences existed with respect to age at onset of schizo-phrenia23,24. Indeed our results are in line with these studies. One of the limitations that could account for this difference in results across the literature is the limited age range for inclusion in the studies, which would not permit a representative sample of the population as a whole. On the other hand, tobacco, alcohol and cannabis are frequently used by schizophrenia patients69,70, as confirmed by the sample in this study. We observed a higher frequency of cannabis consumers among younger men with a first psychotic episode. This result has been described by other authors71,72.

The gender differences observed in the premorbid clinical variables studied are due to the effect of age. These differences are in line with a model for neurodevelopment which indicates that subtle abnormalities could be observed already at PF, especially in early adolescence and a higher number of minor neurological symptoms in persons who later develop the disease. Such aspects would be more frequent in male patients who start a psychotic episode early.

As mentioned previously, there is considerable controversy regarding gender differences with respect to the presentation of symptoms in psychotic disorder spectrum. With respect to positive psychotic symptoms, a large number of studies have reached the conclusion that both men and women experience the same level of positive symptoms23,46, although certain symptoms such as auditory hallucinations and persecutory delusions are more frequent in women44. The analysis regarding prodromic symptoms in our sample comes to similar conclusions, with women showing an early onset of the disease presenting a higher frequency of subclinical senso-perceptive disturbance. Instead, the group of younger men had worse dysfunctional language than women before the onset of psychotic episode.

When symptoms of the first psychotic episode were taken into account, our results were in line with studies that did not find psychopathological differences between men and women with schizophrenia23,49,50. However, the differences found refer to the course of the first episode and not to the expression of initial symptoms. The presence of a higher severity in negative psychotic symptoms and poor awareness of disease, after 8 weeks of evolution of the episode, in the group of males younger than 18 years could suggest the presence of a subpopulation which is more resistant to therapeutic interventions and with worse prognosis. Nevertheless, in line with the results from Cuesta & Peralta52, women in our sample with a later onset of the disease show less awareness of symptoms.

Although a large number of articles has been dedicated to cognitive functioning in patients with schizophrenia, no consensus was reached regarding the observed gender differences. This is mostly due to the variability of instruments of measure utilised to evaluate the different cognitive domains. In line with results by Haas et al.42, no significant differences in gender were observed in executive function, attention and working memory in patients with first psychotic episode. Without doubt, the differences in verbal memory, with men having better capacity, add more data to the divergent results found in the scientific literature. However, we are currently conducting a one year follow-up study of first psychotic episodes which will produce more data regarding questions that still need to be clarified in the literature.

Limitations

Some limitations of the present study are related to the measurement instruments used: Premorbid Adjustment Scale (PAS) and Interview for the Retrospective Assessment of the Onset of Schizophrenia (IRAOS) are instruments for retrospective assessment, in which some information could be inaccurate as it relies on the patients' or family members' memory.

The size of the sample is another limitation for this study and does not permit the extrapolation of the data obtained to the general population. It also makes it difficult to stratify the sample to study and compare different groups (it is necessary to use non parametric tests).

The absence of a control group does not allow to performance a comparison between both populations, health people and patients with a psychotic episode in relation to the premorbid and prodromic variables.

Other limitation is related to patients that have an insidious onset of psychotic episode and not consult to mental health services included in our study. For this reason, not all the first psychotic episodes could be represented in our sample.

Finally, the absence of a control for pharmacological treatment group could influence the analysis of certain variables as well as the symptoms after 8 weeks of evolution of the episode or cognitive functioning. It is a factor which will be taken into account in future analyses. Nevertheless, this limitation is not considered to invalidate the overall conclusions which have been reached in this study.

Conclusion

The most relevant conclusions from our study are the following:

- Women have a higher educational competence than men. In return, men show a higher labour competence than women before onset of the disease.

- No significant differences in gender were observed with respect to onset of the psychotic episode.

- Men are more frequently daily consumers of cannabis whilst women are usually sporadic users.

- Males who started the psychotic epi-sode earlier showed more alterations in premorbid functioning, especially in early adolescence, and a higher number of neurological soft signs.

- Women in early onset showed a higher frequency of senso-perceptive subclinical disturbance (hallucinations) in the prodromic phase.

- Males younger than 18 years show ne-gative psychotic symptoms which are more severe and poorer awareness than females, after 8 weeks of onset the first psychotic episode.

- No gender differences were observed in executive functioning, attention and working memory, although this was different with respect to verbal memory with men having a higher performance.

- Age is an important variable to be considered in future studies about gender differences in psychotic disorders.

The conclusions are important in light of the idea that men and women suffering from schizophrenia show features, characteristics and pecularities typical of their gender. These characteristics should be taken into account to learn more about the different types of onset of the disease, its prevention and possible improvements in therapeutic approach with respect to gender. Finally, it is important to mention that a large part of the discovered gender differences are within the context of a neurodevelopmental model and the existence of alterations in the stages prior to the onset of the disease which predispose its appearance.

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients and families for participating in the study as well as the clinical team at Sant Joan de Déu for their collaboration.

Author Note

GENIPE group is a multidisciplinary group of researchers: Araya S, Arranz B, Arteaga M, Asensio R, Autonell J, Baños I, Bañuelos M, Barajas A, Barceló M, Blanc M, Borrás M, Busquets E, Carlson J, Carral V, Castro M, Corbacho C, Coromina M, De Miquel L, Dolz M, Domenech MD, Elias M, Espezel I, Falo E, Fargas A, Foix A, Fusté M, Godrid M, Gómez D, González O, Granell L, Gumà L, Haro JM, Herrera S, Huerta E, Lacasa F, Mas N, Martí L, Martínez R, Matalí J, Miñambres A, Muñoz D, Muñoz V, Nogueroles R, Ochoa S, Ortiz J, Pardo M, Planella M, Pelaez T, Peruzzi S, Rivero S, Rodriguez MJ, Rubio E, Sammut S, Sánchez M, Sánchez B, Serrano E, Solís C, Stephanotto C, Tabuenca P, Teba S, Torres A, Urbano D, Usall J, Vilaplana M, Villalta V.

References

1. Riecher-Rossler A, Häfner H. Gender aspects in schizophrenia: Bridging the border between social and biological psychiatry. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2000; 102: 58-62. [ Links ]

2. Koster A, Lajer M, Lindhardt A, Rosenbaum B. Gender differences in first episode psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2008; 43: 940-946. [ Links ]

3. Leung A, Chue P. Sex differences in schizophrenia, a review of the literature. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2000; 401: 3-38. [ Links ]

4. McGlashan TH, Bardenstein KK. Gender differences in affective, schizoaffective, and schizophrenic disorders. Schizophr Bull 1990; 16(2): 319-329. [ Links ]

5. Goldstein J, Link B. Gender and the expression of schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res 1988; 22: 141-155. [ Links ]

6. Roy MA, Maziade M, Labbé A, Mérette C. Male gender is associated with deficit schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Schizophr Res 2001; 47: 141-147. [ Links ]

7. Simonsen E, Friis S, Haahr U, Johannessen JO, Larsen TK, Melle I, et al. Clinical epidemiologic first-episode psychosis. 1 year outcome and predictors. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2007; 116: 54-61. [ Links ]

8. Seeman MV, Lang M. The role of estrogens in schizophrenia gender differences. Schizophrenia Bull 1990; 16(2): 185-194. [ Links ]

9. Häfner H, Riecher A, Maurer K, Löffler W, Munk-Jorgensen P, Strömgren E. How does gender influence age at first hospitalization for schizophrenia? A transnational case register study. Psychological Med 1989; 19: 903-918. [ Links ]

10. Murray RM, Lewis SW, Reveley AM. Towards an etiological classification of schizophrenia. Lancet 1985; 4: 1023-1026. [ Links ]

11. Castle DJ, Sham PC, Wessely S, Murray RM. The subtyping of schizophrenia in men and women: A latent class analysis. Psychol Med 1994; 24: 41-51. [ Links ]

12. Murray RM, O'Callaghan E, Castle DJ, Lewis SW. A neurodevolopmental approach to the classification of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1992; 18(2): 319-332. [ Links ]

13. Jerningan TL, Trauner DA, Hesselink JR, Tallal PA. Maturation of human cerebrum observed in vivo during adolescence. Brain 1991; 114: 2037-2049. [ Links ]

14. Flor-Henry P. Gender, hemispheric organization and psychopathology. Soc Sci Med 1978; 12B: 155-162. [ Links ]

15. Häfner H, An Der Heiden W, Behrens S, Gattaz WF, Hambretch M, Löffler W, et. al. Causes and consequences of the gender difference in age at onset of schizophrenia. Schizoph Bull 1998; 24(1): 99-113. [ Links ]

16. Häfner H, Maurer K, Loffler W, An Der Heiden W, Munk-Jorgensen P, Hambrecht M, et al. The ABC schizophrenia study: a preliminary overview of the results. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1998; 33: 380-386. [ Links ]

17. Faraone SV, Chen WJ, Goldstein JM, Tsuang MT. Gender differences in age at onset of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1994; 164: 625-629. [ Links ]

18. Gureje O, Bamidele RW. Gender and schizophrenia: association with age at onset with antecedent, clinical and outcome feature. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 1998; 32: 415-423. [ Links ]

19. Castle DJ, Wessely S, Murray RM. Sex and schizophrenia: effects of diagnostic stringency and associations with premorbid variables. Br J Psychiatry 1993; 162: 658-662. [ Links ]

20. Ochoa S, Usall J, Villalta-Gil V, Vilaplana M, Márquez M, Valdelomar M, et. al. Influence of age at onset on social functioning in outpatients with schizophrenia. Eur J Psychiatry 2006; 20(3): 157-163. [ Links ]

21. Larsen TK, McGlashan TH, Moe LC. First-episode schizophrenia: I. Early course parameters. Schizophr Bull 1996; 22(2): 241-256. [ Links ]

22. Häfner H, Hambrecht M, Loffler W, Munk-Jorgensen P, Riecher-Rossler A. Is schizophrenia a disorder of all ages? A comparison of first episodes and early course across the life-cycle. Psychol Med 1998; 28: 351-365. [ Links ]

23. Addington D, Addington J, Patten S. Gender and affect in schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry 1996; 41(5): 265-268. [ Links ]

24. Naqvi H, Khan MM, Faizi A. Gender differences in age of onset of schizophrenia. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2005; 15(6): 345-348. [ Links ]

25. Amminger GP, Resch F, Mutschlecher R, Fredrich MH, Ernst E. Premorbid adjustment and remission of positive symptoms in first-episode psychosis. Acta Paedopsychiatr 1997; 6(4): 212-216. [ Links ]

26. Childers SE, Harding CM. Gender, premorbid social functioning, and long-term outcome in DSM-III schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1990; 16(2): 309-318. [ Links ]

27. Angermeyer MC, Kuhn L, Goldstein J. Gender and the course of schizophrenia: Differences in treated outcomes. Schizophr Bull 1990; 16(2): 293-307. [ Links ]

28. Mueser KT, Bellack AS, Morrison RL, Wade JH. Gender, social competence and symtomatology in schizophrenia: A longitudinal analysis. J Abnorm Psychol 1990; 99: 138-147. [ Links ]

29. Rabinowitz J, Bromet EJ, Lavelle J, Carlson G, Kovasznay B, Schwartz JE. Prevalence and severity of substance use disorders and onset of psychosis in first-admission psychotic patients. Psychol Med 1998; 28(6): 1411-1419. [ Links ]

30. Larsen TK, McGlashan TH, Johannessen JO, Vibe-Hansen L. First- episode schizophrenia: II. Premorbid patterns by gender. Schizophr Bull 1996; 22(2): 257-269. [ Links ]

31. Norman RMG, Malla AK, Manchanda R, Townsend L. Premorbid adjustment in first episode schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders: a comparison of social and academic domains. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2005; 112: 30-39. [ Links ]

32. Rabinowitz J, Smedt G, Harvey PD, Davidson M. Relationship between premorbid functioning and symptom severity as assessed at first episode of psychosis. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159(12): 2021-2026. [ Links ]

33. Addington J, Mastrigt S, Addington D. Patterns of premorbid functioning in first-episode psychosis: initial presentation. Schizophr Res 2003: 62(1-2): 23-30. [ Links ]

34. Silverstein ML, Mavrolefteros G, Close D. Premorbid adjustment and neuropsychological performance in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2002; 28(1): 157-65. [ Links ]

35. Castle DJ, Murray RM. The neurodevelopmental basis of sex differences in schizophrenia. Psychol Med 1991; 21(3): 565-575. [ Links ]

36. Madsen AL, Vorstrup S, Rubin P, Larsen JK, Hemmingsen R. Neurological abnormalities in schizophrenic patients: a prospective follow-up study 5 years after first admission. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1999; 100: 119-125. [ Links ]

37. Buchanan RW, Heinrichs DW. The Neurological Evaluation Scale (NES): a structured instrument for the assessment of neurological signs in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 1989; 27: 335-350. [ Links ]

38. Rossi A, De Cataldo S, Di Michele V, Manna V, Ceccoli S, Stratta P, et al. Neurological soft signs in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1990; 157: 735-739. [ Links ]

39. Häfner H. Gender differences in schizophrenia. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2003; 28: 17-54. [ Links ]

40. Gutiérrez M, Segarra R, Eguiluz I, Ojeda N, Fernández C. 2 year follow-up of women with first episode schizophrenia or schizophreniphorm disorder treated with risperidone (in press). [ Links ]

41. Ring N, Tantum D, Montague L, Newby D, Balk D, Morris J. Gender differences in the incidence of definitive schizophrenia and atypical psychosis: Focus negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1991; 84: 489-496. [ Links ]

42. Haas Gl, Sweeney JA, Hien DA, Golman D, Deck M. Gender differences in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1991; 4(3): 277. [ Links ]

43. Schultz SK, Miller DD, Oliver SE, Arndt S, Flaum M, Andreasen NC. The life course of schizophrenia: age and symptom dimensions Schizophr Res 1997; 23(1): 15-23. [ Links ]

44. Goldstein JM, Santangelo SL, Simpson JC, Tsuang MT. The role of gender in identifying subtypes of schizophrenia: A latent class analytic approach. Schizophr Bull 1990; 16: 263-275. [ Links ]

45. Szymanski S, Lieberman JA, Alvir JM, Mayerhoff D, Loebel A, Geisler S, et al. Gender differences in onset of illness, treatment response, course and biologic indexes in first-episode schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152(5): 698-703. [ Links ]

46. Shtasel DL, Gur RE, Gallacher F, Heimberg C, Gur RC. Gender differences in the clinical expression of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1992; 7: 225-231. [ Links ]

47. Gur RE, Perry RG, Turetsky BI, Gur RC. Schizophrenia throughout life: sex differences in severity and profile of symptoms. Schizophr Res 1996; 21: 1-12. [ Links ]

48. Lindamer LA, Lohr JB, Harris JM, McAdams LA, Jeste DV. Gender-related clinical differences in older patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry 1999; 60: 61-67. [ Links ]

49. Hayashi N, Igarashi Y, Yamashina M, Suda K. Is there a gender difference in a factorial structure of the positive and negative syndrom scale. Psychopathology 2002; 35: 28-35. [ Links ]

50. Usall J, Ochoa S, Araya S, Gost A, Busquets E y grupo NEDES. Sintomatología y género en la esquizofrenia. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2000; 28(4): 219-223. [ Links ]

51. McEvoy JP, Johnson J, Perkins D, Lieberman JA, Hamer RM, Keefe RS, et al. Insight in first-episode psychosis. Psychol Med 2006; 36: 1385-1393. [ Links ]

52. Cuesta, MJ., Peralta, V., Zarzuela, A. Psychopathological dimensions and lack of insight in schizophrenia. Psychol Rep 1998; 83: 895-898. [ Links ]

53. Goldstein JM, Seidman LJ, Santangelo S, Knapp PH, Tsuang MT. Are schizophrenic men at risk for developmental deficits than schizophrenic women? Implications for adult neuropsychological functions. J Psychiatr Res 1994; 28(6): 483-498. [ Links ]

54. Seidman LJ, Goldstein JM, Goodman JM, Koren D, Turner WM, Faraone SV, et al. Sex differences in olfactory identification and Wisconsin Card Sorting performance in schizophrenia: relationship to attention and verbal ability. Biol Psychiatry 1997; 42: 104-115. [ Links ]

55. Goldberg TE, Gold JM, Torrey EF, Weinberger DR. Lack of sex differences in the neuropsychological performance in patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152: 883-888. [ Links ]

56. Andia AM, Zisook S, Heaton RK, Hesselink J, Jernigan T, Kuck J, et al. Gender differences in schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis 1995; 183(8): 522-528. [ Links ]

57. Perlick D, Mattis S, Stastny P, Teresi J. Gender differences in cognition in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1992; 8: 69-73. [ Links ]

58. Lewine RRJ, Walker EF, Shurett R, Caudle J, Haden C. Sex difference in neuropsychological functioning among schizophrenic patients. Am J Psychiatry 1996; 153: 1178-1184. [ Links ]

59. Cannon-Spoor HE, Potkin SG, Wyatt RJ. Measurement of premorbid adjustment in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1982; 8: 470-484. [ Links ]

60. Lopez M, Rodriguez S, Apiquian R, Paez F, Nicolini H. Translation study and validation of the Premorbid Adjustment Scale for Schizophrenia. Salud Mental 1996; 19: 24-29. [ Links ]

61. Häfner H, Riecher-Rössier A, Hambrecht M, Maurer K, Meissner S, Schmidtke A, et al. IRAOS: an instrument for the assessment of onset and early coruse of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 1992; 6(3): 536-548. [ Links ]

62. Kay SR, Fizbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1987; 13(2): 261-276. [ Links ]

63. Peralta V, Cuesta MJ. Validación de la Escala de los Síndromes Positivo y Negativo (PANSS) en una muestra de esquizofrénicos españoles. Actas Luso-Esp Neurol Psiquiatr 1994; 22(4): 1-7. [ Links ]

64. Villalta-Gil V, Vilaplana M, Ochoa S, Dolz M, Usall J, Haro JM, et al. Four Symptom dimensions in outpatients with schizophrenia. Compr Psychiatry 2006; 47(5): 384-388. [ Links ]

65. Haro JM, Kamath SA, Ochoa S, Novick D, Rele K, Fargas A, et al. The Clinical Global Impression-Schizophrenia scale: a simple instrument to measure the diversity of symptoms present in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2003; 416: 16-23. [ Links ]

66. Endincott J. The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33: 766-771. [ Links ]

67. Amador XF, Strauss DH, Yale SA, Gorman JM. Awareness of illness in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1991; 17: 113-132. [ Links ]

68. Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: Reliability, validity and sensitivity. Br J Psychiatr 1978; 133: 429-435. [ Links ]

69. Hambrecht M, Häfner H. Substance abuse and the onset of schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 1996; 40: 1155-1163. [ Links ]

70. Mueser KT, Yarnold PR, Bellack AS. Diagnostic an demographic correlates of substance abuse in schizophrenia and major affective disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1992; 85(1): 48-55. [ Links ]

71. Hall WD. Cannabis use and psychosis. Drug Alcohol Rev 1998; 17: 433-444. [ Links ]

72. Rodríguez-Jiménez R, Bagney A, Jiménez-Arriero MA, Aragüés M, Koenecke A, Cubillo AI, et al. Esquizofrenia y trastornos adictivos: Comorbilidad en pacientes psiquiátricos agudos ingresados. Psiq Biol 2006; 13 (S3): 46-47. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Susana Ochoa

Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu

C/ Antoni Pujades 42. CP 08830

Sant Boi de Llobregat (Spain)

Tel. +34 93 640 63 50

Fax. +34 93 630 53 19

E-mail: sochoa@pssjd.org

Received: 2 January 2009

Revised: 14 May 2010

Accepted: 14 May 2010