Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

The European Journal of Psychiatry

versión impresa ISSN 0213-6163

Eur. J. Psychiat. vol.26 no.1 Zaragoza ene./mar. 2012

https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S0213-61632012000100001

Use of functioning-disability and dependency for case-mix and subtyping of schizophrenia

Susana Ochoa*; Luis Salvador-Carulla**; Victoria Villalta-Gil*; Karina Gibert***; Josep Maria Haro*; DEFDEP Group

* Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu Research Unit. CIBERSAM, Spain

** Division of Disability and Mental Health. Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Sydney, Australia

*** Departamento de Estadística e Investigación Operativa. Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya. Knowledge Discovery and Machine Learning group. Universitat Politecnica de Catalunya, Spain

This Project has been funded by the Agency of Dependency of Catalonia (Prodep) and the Departament de Salut de la Generalitat de Catalunya.

ABSTRACT

Background and Objectives: To evaluate the utility of the constructs functioning and disability (F & D) and dependency for case-mix and subtyping of patients with schizophrenia by psychosocial, clinical, use of services and attention received from informal carers.

Methods: A randomly selected total of 205 people with schizophrenia, and their careers were evaluated through PANSS, DAS-sv, Objective and Subjective Burden Scale (ECFOS-II) and use of services.

Results: Two groups and Four profiles were identified according to levels of Dependency: The non-dependent group was made of two profiles: independent (I), and persons with disability in the community (DiC). The dependent group included persons with dependency in the community (DeC) and persons with dependency in hospital care (DeH). There are clinical and psychosocial differences between these profiles being the dependent the most severe. Regarding use of services, DeC use the most resources, with the exception DeH (more hospitalization resources). The DeC profile generate greater family burden in the following areas; taking medication, being accompanied to appointments, and management than the DiC, despite both groups showing a high need for support.

Conclusions: Dependency is a relevant construct for case-mix and subtyping in schizophrenia, and it is related to severity both at the social and clinical level. DeC generate more family burden than the other profiles, followed by DiC (patients with schizophrenia with disability but non-dependent).

Key words: Functioning; Disability; Dependency; Schizophrenia; Family burden.

Introduction

In the 1990's the Council of Europe defined "dependency" as the condition related to the loss of autonomy and the need of support from a third person due to impairment of activities of daily living, especially self-care. Laws and care services for the elderly and for people with severe disability including severe mental illness have been developed following this paradigm in many European countries1. In Spain the Law of Dependency was enacted in 2006 and regional Agencies of Dependency were progressively implemented. Unfortunately this legal and service development in Europe has not been accompanied by a formal definition of the construct of "functional dependency" and its relation to other constructs such as autonomy, disability and functioning. Two parallel and non-related concepts lay behind the use of this name in European health and social care. On the one side, "functional dependency" has been conceptualised as an impairment of the Activities of Daily Living model (ADLs)2-5. On the other, "functional dependency" has been related to the WHO model of functioning which has been described at the International Classification of Functioning (ICF)6, even though this model does not include any reference to "dependency"5. This terminological confusion has led to flagrant contradictions, problems in implementation and it has casted doubts on the usability of the assessment and the construct of dependency in long-term care in countries such as Spain, France or Germany7. In Spain the law is related to the ICF model while the assessment instrument for eligibility benefits related to dependency is based on the ADLs model1and the current variability in concepts impedes comparability of care systems for dependency across countries4.

Severe mental disorders are the population group where eligibility and care delivery problems are more evident5. In this group there is debate over the physical possibility of performing a task and the inability to carry it out due to the disorder, and how this inability generates a need for care on the part of the family for the patient8. In addition, a different conceptual model of functioning related to the burden of disease has also been applied in this population group.

No previous studies have assessed the levels of dependency of the patients with schizophrenia and the relationship with symptoms, social functioning and services use. However, some researchers have demonstrated that high levels of help from the caregivers are associated with a worse social functioning9, more symptoms (especially negative)10,11 and more use of services12 of the patients that they take care.

The objective of the present study is to evaluate the degree of dependence shown by a sample of people with schizophrenia who live in community, and the relationship between the degree of dependence and sociodemographic, clinical, disability, service use, and formal and informal care variables.

Method

The DEFDEP group (DEFinition of DEPendency in mental disabilities) included a working group who carried out a panel of experts and a secondary data analysis in relation to results of the panel experts13. The panel used a nominal technique14 to produce a formal definition of dependency applied to mental disorders based on the ICF model, and with an operational criterion of dependency for schizophrenia.

Formal definitions, operational criteria and subtyping

Health-related "environmental functional dependency" was defined as a state derived from a permanent or long-term health condition which limits the daily life of a person to the extent that there is a need for the aid of others, or other exceptional help to allow the person to manage their immediate environment5.

The panel defined 4 types of groups of people with schizophrenia:

1. Independent (I): GAF score of above 70 over the last year, living alone or with a partner, working or studying.

2. Disability in the community (DiC): functional limitation without dependence: non-independent, no-dependent patients (this is a group defined by exclusion).

3. Dependency in the Community (DeC): Non-institutionalised patients (less than 330 days in residential care in the last year); GAF score in the last year less than 50, Prudo and Blum criterion of IVb.

4. Dependency in Hospital (DeH): admitted for more than 330 days in a residential-type unit with a score of less than 50 in the GAF.

Subjects

The secondary data analysis was carried out using data from the PSICOST-II study. It is a naturalistic study of administrative prevalence of a representative sample of prevalence of outpatients with schizophrenia between 18 and 65 years.

People with schizophrenia (DSM-IV criteria) who were being attended in: Mental health centre of Gava (Barcelona); Mental health centre of Loja (Granada), Mental health centre of Salamanca neighborhood (Madrid) and mental health centre of Burlada (Pamplona) were randomly selected through the administrative register. The study was approved by all Ethics Committees of participating centers. More information about the method of the study is provided in Vazquez-Polo et al. (2005)15.

Description of study sample

Evaluation included 356 patients, of whom 329 cases completed the assessment. A total of 205 careers were also interviewed. No differences were found between the people who complete the evaluation and those who have not.

The predominant profile of people evaluated in the study is: men (68%), single (77%), primary education (49%), drawing a pension / benefits (62%) and living mainly with their parents (67%).

Procedure

People included in randomized sample were asked for their participation in the study. Those who signed the written voluntary informed were assessed by their psychiatrist or an expert psychologist trained in the instruments of the study. The assessment consists in two evaluations: one with the patient and the second the main career.

Evaluation instruments

Patients participating in the study were evaluated with the following questionnaires:

- CECE Questionnaire: collects sociodemographic, clinical and service-use data. It provides information regarding the intensity of formal service use including the number of admissions and stays in psychiatric and general hospital services for acute, subacute and medium and long-stay, as well as day hospitals, day centres and the number of appointments with mental health centre (MHC) professionals. It has been used in cost studies carried out by the PSICOST group15. The calculation of formal care services hours was carried out by adding the MHC care hours as 0.5 hours, day-hospital as 8 hours per day, day-centre and occupational therapy as 2 hours per day, and hospital and residential services as 24 hours per day of admission.

- Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for Schizophrenia (PANSS)16,17. This is divided into three subscales which measure positive, negative and general symptoms. Positive and negative scales rated 7-49 and the general scale rated between 16-112. Higher scores indicate greater levels of symptoms. This scale has demonstrated high validation properties.

- General Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF)18 translated into Spanish in the DSM-IV (1995). This scale evaluates global functioning at the clinical and social level. Higher scores indicate better functioning on a scale of 0-100.

- Disability Assessment Scale, short version (DAS-sv)19, evaluates disability on four subscales: personal care, occupational level, family relationships, and other social relationships. The punctuations rated in each subscale between 0-5, where higher scores indicate greater levels of disability.

- EuroQol Quality of Life Questionnaire20,21 This is a generic instrument for measuring health-associated quality of life. It consists of two sections: in the first, the individual describes his/her health problems in five dimensions (mobility, personal care, daily activities, pain and anxiety/depression) with three levels of severity in each. In the second, the individual evaluates his or her health on a scale of 0-100, when higher punctuations indicated better quality of life. This scale has been used for several populations and the psychometric properties for the sample of schizophrenia are good.

- Objective and Subjective Family Burden Scale (ECFOS-II)22. This is a heteroapplied interview to evaluate the burden on principal carers of people with schizophrenia who live in the community. The validation of the scale show high psychometric properties. The interview is conducted with the family member identified as the main carer. It evaluates the help given to the patient in daily life activities (module A), prevention and avoidance of disrupted behaviours (module B), a list of economic expenses (module C), the impact on the carer's life (module D), reasons for concern for the patient (module E), the help available (module F), perceived affects on health (module H) and the global repercussions experienced at the individual and family level (module I). The scale assesses the need of support in this areas, the preoccupation for taking care and the number of hours spend in helping their career. For the objectives of this study the total number of hours that the carer dedicates to the care of the person suffering from schizophrenia is taken into account in a series of areas related to the concept of disability previously explain. The areas included were the following items of the module A: personal care, taking medications, household tasks, shopping, meal, travel, money management, time allocation, appointment accompany and management, and the help from third person with daily activities assessed in the module F. Independent people in the sample did not score on the family burden questionnaire.

- Case-mix. Two scales were used for the case-mix: The Prudo and Blum23 (PB) classification and the Ontario levels of care scale24. PB classifies patients according to course, duration and intensity of care. The classification includes: Group I, only one episode of schizophrenia with an average duration of 22 weeks; Group II, only one episode of severe disorder up to one year in duration; Group III, episodes from 1 to 2.5 years; Group IVa, episodes of more than 2.5 years and which require community treatment fundamentally, and Group IVb, episodes of more than 2.5 years and which require hospital treatment along with intensive community programmes.

Ontario scale defines 5 levels of care. It was used in combination with the levels of PB for the case-mix. PB-IVb was further divided in three levels according to the Ontario scale. Ontario 3: patients with Prudo and Blum IVb and use of day-centre and/or hospital services in the last year; Ontario 4: patients with Prudo and Blum IVb and use of day-centre and/or hospital services and hospitalisations in the last year; Ontario 5: patients who have been hospitalised in the last year independent of the degree of PB-IVb.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis of the data was performed using the Chi2 for comparing qualitative variables with the four groups of patients. The variance analysis (ANOVA), was used for comparing quantitative variables with the four groups of patients; and the Kruskall-Wallis analysis for relating the four groups of patients with ordinal variables.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics related by groups

Table 1 shows the comparison of sociodemographic variables in the four dependence groups. Significant differences exist between the groups with regard to the variables: educational level (p<0.005), sources of income (p<0.01) and living circumstances (p<0.001). We observed that the group of dependents have a higher educational level and usually work and live independently while those in the institutionalised group usually live more with the family. The DiC and dependent groups differed in that in the former there are more people who work and a higher percentage who live independently.

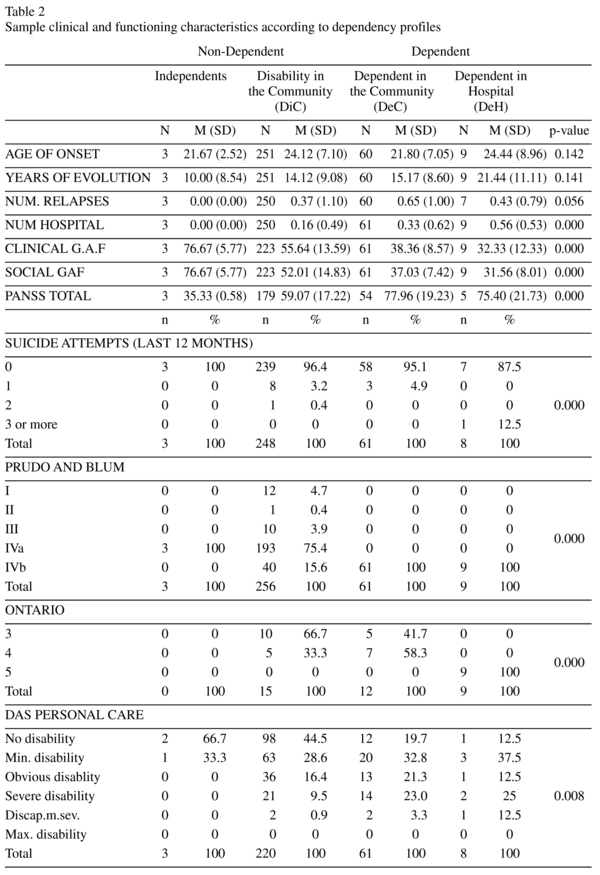

Patients clinical characteristics and functioning

The clinical characteristics according to groups dependence criteria are shown in table 2. The number of hospitalisations is higher in those people in the dependent group (community and hospital) (p<0.001). People in the DeC group along with those people in the DeH group are those who present the worst GAF scores and the most severe PANSS scores (p<0.001). The number of suicide attempts is higher in the DeH group despite the fact that they are admitted to institutions and are under constant supervision (p<0.001).

There are significant differences in the GAF general and social scores (p<0.001), as well as in each of the disability questionnaire subscales (p<0.001).

Description of service use

Table 3 shows the average use of clinic and hospital services and the daily activities in each of the dependence groups. Persons with DeC in the sample are attended on more occasions by the clinic psychiatrist than the rest of the groups (p<0.05). On the other hand, independent people are those that are visited least by the MHC social worker, even with respect to residential patients (p<0.05). People in the DeC group show a higher use of day-hospital services (p<0.05). With respect to hospitalisation services, there are significant differences in the use of medium and long-stay and residential services, as was expected there is greater use in the DeH group (p<0.001).

Family burden characteristics

In the evaluation of family burden we find that the daily life activities where the highest number of patients receives most informal help are: household tasks (44.9%), time-allocation (43.7%), money management (30.8%) and personal care (30.3%). The results show that 68% of the families evaluated have another person available to assist the principal carer in looking after the person with mental illness. It should be pointed out that 22% of those people with schizophrenia have a second carer available who invests more than 21 hours in caring for them. These secondary carers dedicate time to limiting inappropriate behaviour (in 37% of cases), the consequences of aggressive behaviour (in 22% of cases) and to the consequences of inappropriate behaviour (in 21% of cases). Another point that should be highlighted is that more than 6% of sample patients need more than 21 hours of help per week from family members to deal with problematic behaviour. Table 4 shows module items "A" and "F" of the ECFOS-II. In DeH group the scores are low as they have been admitted and receive attention mainly from formal services. Although significant differences appear in the taking of medication (p<0.001), being accompanied to appointments (p<0.01) and management (p<0.001), distribution by percentage is not very different between the three profiles (DiC, Dec, DeH) which indicates to us that the hours of help received from family members in the groups is similar. There are no significant differences between the dependence groups in any of the items of prevention and avoidance of disrupted behaviours.

Hours of care received by the patients

Table 5 shows the care hours (formal, informal and total) in each of the dependence groups. It should be noted that more than 40% of the DiC profile receive more than 21h/week of informal care (from unpaid carers or family members); which is even greater in the DeC group (55%); despite no significant differences were found (p = 0.71). With respect to the hours of formal support, significant differences were found with a high degree of care on the part of health services and social/health services in the DeH group (87.5% receive more than 21 h/week) The percentage of people of each group that receives a total support (formal and informal) up to 21h/weeks is 46.8% in the DiC profile, 72.5% in the DeC-group and 100% in the DeH group.

Discussion

The criteria established by the consensus group show four groups with differential characteristics. Level of global functioning (GAF, living alone and working/studying), years of evolution of the illness and services needed are discriminative variables that could be of use in the evaluation of the degree of dependence in people with schizophrenia. Although one of the biggest problems of this classification is the low number of cases in the extreme groups (independents and DeH). The independence group is lower in our sample comparing with longitudinal studies of prognosis that found around 20% of good outcome25,26.

The clinical profile of dependent people (DeC or DeH) is very severe at the level of symptoms, admissions and number of suicides. The results indicate to us that the people who are assigned to the group of dependents (DeC or DeH) are those who obtain the lowest scores in the social GAF and in the total which indicates people with severe problems in social relationships and community integration27.

With respect to disability it can also be observed that there is a greater percentage of people that belong to the dependent group (DeC or DeH) who obtain the highest disability scores in all. In the occupational DAS it can be seen that the group of independents does not have disability problems in this area; nevertheless, more than 50% of people who belong to the other three groups do.With respect to the family DAS, we observe that the sample of residential patients have severe family problems, and this may be the reason why they are admitted to hospital or residential services28. The results provide evidence that dependent people in the sample are those who present the greatest problems in psychosocial functioning, and those people in the group of independents stand out due to their level of integration in community social activities. It seems that dependence is determined by symptoms and by disability, and by the relation between the two variables29.

In the evaluation of family burden in carers we find that the families are covering the patient's basic needs in various aspects of daily life activities. The independent and DeH groups show the lowest family burden, because they do not require the care or because they are disconnected from their families. However, in the comparison between the DiC and the DeC profiles we can observe that informal support is high in both groups and higher in the latter. Considering that these groups are the more prevalent of our sample, it is important in mental health planning to bear in mind the total number of hours which informal carers dedicate to supporting patients in daily life activities as these are the main providers of care and social network30. In both groups more than 40% of patients require more than 21 hours of care per week. This generates high levels of family burden as the carer dedicates many hours to the supervision or care of the ill person9 and, in addition, the family burden levels are higher depending on the presence of symptoms and disability on the part of the patient31-33. The basic difference between the DiC and DeC groups is shown by the number of hours of health resources. As such, we could say that dependent people not only receive a high level of support from their families but also receive high levels of support from established formal services34.

It is important to use uncomplicated indicators which complement the information to assess the degree of functional dependence in specific areas such as psychiatry or neurology35.

Acknowledments

- CIBERSAM y RedIAPP.

Other members of the DEFDEP group (severe mental disorders) were Cristina Molina, Josep Ramos, Miquel Casas, Antoni Bulbena, and Teresa Marfull.

- The PSICOST group is a multidisciplinary team composed of psychiatrists, economists, pharmacologists, psychiatric nurses and public-health workers in health-service research in mental health and disability. Other PSICOST Group members are Susana Araya, Juan Cabases, Pedro Enrique Muñoz, Alexandrina Foix, Alfredo Martinez, Susana Nadal, Cristina Romero, Rafael Martinez, Miriam Poole, Juan Carlos García-Gutierrez and Francisco Torres.

References

1. Salvador-Carulla L, Gibert K, Ochoa S. Definition of "functional dependency" implications for health and social policy. Aten Primaria 2010; 42(6): 344-345. [ Links ]

2. IMSERSO. El libro blanco sobre la atención a las personas en situación de dependencia en España. Madrid: Imserso; 2004. www.imsersomayores.csic.es/documentos/documentos/libroblancodependencia/mtas-libroblancointro-01.pdf [ Links ]

3. Rodríguez-Cabrero G, Montserrat-Codorniu J. Una aproximación a los costes de la dependencia. Madrid: Observatorio de Mayores: IMSERSO; 2002. [ Links ]

4. Grammenos S. Feasibility study. Comparable statistics in the area of care for dependent authors in the European Union. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; 2003. [ Links ]

5. Salvador-Carulla L, Gasca VI. Defining disability, functioning, autonomy and dependency in person-centered medicine and integrated care. Int J Integr Care 2010; 10 Suppl: e025. [ Links ]

6. World Health Organisation. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (CIF). Geneva: WHO; 2001. [ Links ]

7. Albarrán Lozano I, Alonso González P, Bolancé Losillas C. A comparison of the Spanish, the French and the German valuation scales to measure dependency and public support for people with disabilities. Rev Esp Salud Pública 2009; 83(3): 379-392. [ Links ]

8. Ochoa S, Haro JM, Autonell J, Pendàs A, Teba F, Màrquez M; NEDES Group. Met and unmet needs of schizophrenia patients in a Spanish sample. Schizophr Bull 2003; 29(2): 201-210. [ Links ]

9. Ochoa S, Vilaplana M, Haro JM, Villalta-Gil V, Martínez F, Negredo MC, et al. Do needs, symptoms or disability of outpatients with schizophrenia influence family burden? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2008, 43(8): 612-618. [ Links ]

10. Magliano L, Fiorillo A, Rosa C, Maj M; National Mental Health Project Working Group. Family burden and social network in schizophrenia vs. physical diseases: preliminary results from an Italian national study. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2006; 429: 60-63. [ Links ]

11. Addington J, Collins A, Mc Cleery A, Addington D. The role of family work in early psychosis. Schizophr Res 2005; 79(1): 77-83. [ Links ]

12. Joseph R, Birchwood M. The national policy reforms for mental health services and the story of early intervention services in the United Kingdom. J Psychiatry Neurosci 2005, 30(5): 362-365. [ Links ]

13. Salvador-Carulla L, Gibert K, Ochoa S, Martorell A, Nadal M, Villalta V, et al. Evaluación de la dependencia en el trastorno mental grave y la discapacidad intelectual. Informe CatSalut, Generalitat de Catalunya; 2006. [ Links ]

14. Delbecq AL, Van de Ven AH, Gustafson DH. Group techniques for program planning: A guide to nominal group and Delphi processes. Glenview, Illinois: Scott, Foresman and Company; 1975. [ Links ]

15. Vazquez-Polo FJ, Negrin M, Cabasés JM, Sanchez E, Haro JM, Salvador-Carulla L. An analysis of the costs of treating schizophrenia in Spain: a hierarchical Bayesian approach. J Ment Health Policy Econ 2005; 8(3): 153-165. [ Links ]

16. Kay SR, Opler LA, Fiszbein A. The positive and negative symptom scale (PANSS). Rating manual. Social Behav Sci Doc 1986; 17: 28-29. [ Links ]

17. Peralta V, Cuesta MJ. Validación de la escala de los síndromes positivo y negativo en una muestra de esquizofrénicos españoles. Actas Luso Esp Neurol Psiquiatr Cienc Afines 1994, 22(4): 171-177. [ Links ]

18. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Coen J. The Global Assessment Scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1976; 33: 766-771. [ Links ]

19. Janca A, Kastrup M, Katschnig H, López-Ibor JJ, Mezzich JJE, Sartorius N. The World Health Organization Short Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO DAS-S): a tool for the assessment of dificulties in selected areas of functioning of patients with mental disorders. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1996; 31: 349-354. [ Links ]

20. Brooks R. EuroQol: The Current State of Play. Health Policy 1996; 37: 53-72. [ Links ]

21. Badía X, Salamero M, Alonso J, Ollé A. La Medida de la Salud. Guía de escalas de medición en español. Barcelona: PPU; 1996. [ Links ]

22. Vilaplana M, Ochoa S, Martínez A, Villalta V, Martínez-Leal R, Puigdollers E, et al. Validación en población española de la entrevista de carga familiar objetiva y subjetiva (ECFOS-II) para familiares de personas con esquizofrenia. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2007; 35(6): 372-381. [ Links ]

23. Prudo R, Blum HM. Five-year outcome and prognosis in schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry 1987; 150: 345-354. [ Links ]

24. Durbin J, Cochrane J, Goering P, MacFarlane D. Needs-Based Planning: Evaluation of a Level-of-Care Planning Model. J Behav Health Serv Res 2001; 28(1): 67-80. [ Links ]

25. Breier A, Schreiber JL, Dyer J, Pickar D. National Institute of Mental Health Longitudinal Study of Chronic Schizophrenia Prognosis and Predictors of Outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1991; 48(3): 239-246. [ Links ]

26. Harrow M, Jobe TH. How frequent is chronic multiyear delusional activity and recovery in schizophrenia: a 20-year multi-follow-up. Schizophr Bull 2010; 36(1): 192-204. [ Links ]

27. Schwartz RC. Concurrent validity of the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale for clients with schizophrenia. Psychol Rep 2007; 100(2): 571-574. [ Links ]

28. Preti A, Rucci P, Santone G, Picardi A, Miglio R, Bracco R, et al.; PROGES-Acute group. Patterns of admission to acute psychiatric in-patient facilities: a national survey in Italy. Psychol Med 2009; 39(3): 485-496. [ Links ]

29. Alptekin K, Erkoç S, Gög üs AK, Kültür S, Mete L, Uçok A, et al. Disability in schizophrenia: clinical correlates and prediction over 1-year follow-up. Psychiatry Res 2005, 15; 135(2): 103-111. [ Links ]

30. Tucker C, Barker A, Gregorie A. Living with schizophrenia: caring for a person with a severe mental illness. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1998; 33: 305-309. [ Links ]

31. Koukia E, Madianos MG. Is psychosocial rehabilitation of schizophrenic patients preventing family burden? A comparative study. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs 2005; 12(4): 415-422. [ Links ]

32. Lowick B, De Hert M, Peeters E, Wampers M, Gilis P, Peuskens J. A study of the family burden of 150 family members of schizophrenic patients. Eur Psychiatry 2004; 19(7): 395-401. [ Links ]

33. Perlick DA, Rosenheck RA, Kaczynski R, Swartz MS, Canive JM, Lieberman JA. Components and correlates of family burden in schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 2006; 57(8): 1117-1125. [ Links ]

34. Pezzimenti M, Haro JM, Ochoa S, González JL, Almenara J, Alonso J, et al. Assessment of service use patterns in out-patients with schizophrenia: a Spanish study. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2006; 432: 12-18. [ Links ]

35. Leon-Carrion J, Martin-Rodriguez JF, Damas-Lopez J, Barroso JM, Martin Y, Dominguez-Morales MR. A QEEG index of level of functional dependence for people sustaining acquired brain injury: The Seville Independence Index (SINDI). Brain Injury 2008; 22(1): 61-74. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Susana Ochoa

Research Unit Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu

CIBERSAM

C/ Dr Pujades 42. Sant Boi de Llobregat

Barcelona (Spain)

Tel: 0034 936 406 350 (ext: 2538)

E-mail: sochoa@pssjd.org

Received: 20 December 2010

Revised: 3 May 2011

Accepted: 30 May 2011