Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.107 no.4 Madrid abr. 2015

ORIGINAL PAPERS

The irritable bowel syndrome care process from the patients' and professionals' views

Opiniones sobre el proceso asistencial de los pacientes con síndrome de intestino irritable

José Joaquín Mira1,2,3, Mercedes Guilabert2, Laura Sempere4, Isabel M. Almenta4, José María Palazón4, Emilio Ignacio García5,6 and Enrique Rey7,8

1Department of Health of Alicante. Sant Joan, Alicante. Spain.

2Department of Health Psychology. Universidad Miguel Hernández. Elche, Alicante. Spain.

3REDISECC, Red de Servicios de Salud Orientados a Enfermedades Crónicas.

4Department of Digestive Diseases. Hospital General Universitario de Alicante. Alicante, Spain.

5Department of Nursing and Physiotherapy. Universidad de Cádiz. Cádiz, Spain.

6SECA. Sociedad Española de Calidad Asistencial.

7Department of Digestive Diseases. Hospital Clínico San Carlos. Madrid, Spain.

8Department of Medicine. Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Madrid, Spain

This study was funded by the pharmaceutical company Almirall, S.A.

ABSTRACT

Background and purpose of the study: This study assessed the experiences of irritable bowel syndrome patients with the healthcare system. Specifically, this study focused on the barriers that patients found.

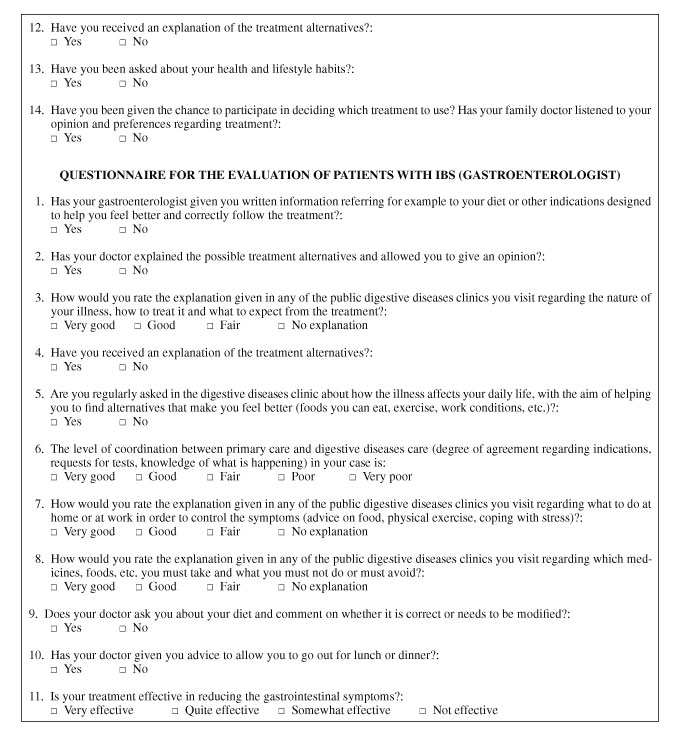

Methods: Three focus groups were conducted with the participation of 19 patients and 10 healthcare professionals. From this information a script of questions was designed and 33 structured interviews were conducted. Finally, a scale for evaluation of the perception of patients was designed for primary care (14 items) and gastroenterology (13 items). Internal consistency and construct validity were calculated.

Results: The difficulties of accessibility, to clarify doubts, concerns regarding uncertainty, reduced information about prognosis and its social and labour effects were the most cited by patients. Low adherence and persistence in the treatment plan were the problems cited most often by professionals. The items of the scale for primary care were grouped into 4 factors (explained variance, 73%), while those for gastroenterology were grouped into 3 factors (explained variance, 67%). The internal consistency was 0.84 and 0.82, respectively. A total of 29 (88%) patients were satisfied with the care provided in gastroenterology, while 24 (73%) declared themselves satisfied with the primary care physician (Chi-square 2.4, p = 0.21). This study was carried out from November 2013 to July 2014.

Conclusions: This study describes the most relevant problems in the assistance received by these patients.

Key words: Irritable bowel syndrome. Care quality. Care path. Perception.

RESUMEN

Antecedentes y propósito del estudio: en este estudio se evaluó la experiencia de los pacientes con síndrome de intestino irritable (SII) con el sistema sanitario analizando específicamente las dificultades con las que se encuentran estos pacientes.

Métodos: para identificar cuestiones clave se condujeron 3 grupos focales con participación de 19 pacientes y 10 profesionales sanitarios. A partir de estas informaciones se diseñó un guión de preguntas y se realizaron 33 entrevistas estructuradas a pacientes con SII. El estudio de campo se realizó entre noviembre de 2013 y julio de 2014. Finalmente con esta información se diseñó una escala de valoración de la percepción de los pacientes de las atenciones que reciben en atención primaria (14 ítems) y digestivo (13 ítems), analizando validez de constructo y consistencia interna.

Resultados: las dificultades de accesibilidad, para resolver dudas, preocupación derivada de la incertidumbre, reducida información sobre pronóstico y sus afectaciones sociales y laborales fueron las más citadas por los pacientes. Bajo cumplimiento y baja persistencia en el plan terapéutico fueron los problemas citados con mayor frecuencia por los profesionales. Los ítems de la escala para atención primaria confluyeron en 4 factores (varianza explicada, 73%), mientras que para digestivo confluyó en 3 factores (varianza explicada, 67%). La consistencia interna fue de 0,84 y 0,82, respectivamente. Un total de 29 (88%) pacientes se manifestaron satisfechos con la atención prestada en digestivo, mientras 24 (73%) se declararon satisfechos con el médico de atención primaria (Chi-Cuadrado 2,4, p = 0,21).

Conclusiones: este estudio describe los principales problemas asistenciales desde la perspectiva del paciente.

Palabras clave: Síndrome de intestino irritable. Calidad asistencial. Ruta asistencial. Percepción.

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a highly prevalent disorder, affecting 3-10% of the Spanish population. Women are more frequently affected than men (ratio 2-2.5/1) (1), and about 40% of all patients seek medical help at some point during the year (2). It has been estimated that IBS accounts for 2-15% of all consultations in primary care (PC) and up to 30% of all specialized consultations in gastroenterology (digestive diseases). Although a clinical guide on the management of IBS has been published (the AEG guide), the fact is that the diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to the disease vary among both gastroenterologists and PC physicians (3).

Irritable bowel syndrome has a strong impact upon patient quality of life. In effect, patients with IBS suffer disturbances in their social and professional life, and feel ashamed of their symptoms. They often change their eating habits and frequently resort to the healthcare services in a futile search for effective medical care (4,5). These are patients for which no concrete answer is available, and their medical care is conditioned by psychosocial factors, the attitudes of the professionals and patients themselves, the comorbidities and severity of the symptoms, and mistaken concepts about the disease (6-8).

The information received by the patients, the coordination among different healthcare levels, and the diagnostic response capacity are key factors in the care process, since the physicians and patients tend to disagree on their perception of the influence of psychological variables in IBS (9). Patient scepticism characterizes the relationship with the medical professionals. Patients with IBS normally are not satisfied with the treatment they are receiving and actively seek information on other possible alternatives. They perceive no clear benefit from the prescribed therapy and complain about significant shortcomings in the information they receive (10). Previous studies have evaluated patient perception referring to colonoscopy (11), and a 38-item questionnaire has been developed to assess patient satisfaction with the care received in the context of the management of IBS (12). In this latter study satisfaction was positively correlated to a quality of life measure (IBS-QOL) (13) and negatively to the level of psychological stress reported by the patient. Some years earlier, this same research group (14) conducted a study on the symptoms most frequently reported by patients with IBS. They found that 47% were dissatisfied with the care provided, though 73% of the patients had a positive opinion about the treatment they were receiving at that time.

Studies have been made of the quality of the patient-physician relationship (15), with the identification of a larger number of negative (n = 106, 54%) than positive comments (n = 22, 11%). The evaluation of patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) and of patient reported experience measures (PREMs) can contribute to introduce changes in patient care, when such data is used by clinicians in their decision making processes (16,17). However, we do not know the perception of patients with IBS regarding the healthcare process applied to them, and there are no Spanish population based studies on the perception of patients with IBS regarding the medical care they receive. The present study evaluates the opinion of patients with IBS regarding their experience with the healthcare system in Spain, and conducts a specific analysis of the difficulties these patients commonly face both in primary care and in specialized gastroenterological consultation.

Method

A phenomenological, observational study based on qualitative investigational techniques (focus group technique and structured interviews) was carried out. The focus group technique (18) was used to analyze patient and professional opinion regarding the way in which the patients experience the medical care they receive for IBS, the main difficulties they find, and their most frequent mistakes in relation to treatment or diet. Structured interviews, with the application of scales specifically designed for this study, were used to gain insight to the aspects of medical care in patients of this kind and which were identified as key elements by the participants in the focus groups.

We established three focus groups with a duration of about two hours each [one with 10 professionals (PC physicians, specialists in gastroenterology, psychiatry, clinical psychology, medical inspection and nursing) and two with 8 and 11 patients, respectively]. This allowed triangulation of the contributions, with identification of the salient common ideas. No personal information or clinical data from any source was collected. Consent was obtained from all the participants, following the indications of the Project Evaluating Body of Universidad Miguel Hernández in Elche (Alicante, Spain) (2014.305E.OEP).

The field work was conducted in Alicante (Hospital General Universitario de Alicante, Spain) and in Madrid (Hospital Clínico San Carlos. Madrid, Spain) between November 2013 and July 2014. In the case of the professionals, we applied the following inclusion criteria: At least 5 years of experience in the care of patients with IBS, with an even (50%) distribution between males and females. In the case of the patients the inclusion criteria were: Functional disorders with a diagnosis of IBS, a disease duration of at least 5 years, a possible history of psychiatric, mental health or rheumatologic consultations, and a male/female ratio of 2/3. Since age is positively correlated to satisfaction (19), we included patients belonging to different age groups, in order to compensate this possible effect.

The focus groups were conducted by two professionals with experience in the technique (JJM and MG). A list of key questions and cluster questions was developed by consensus among the members of the research team, with the purpose of exploring the following study parameters: Information on IBS (nature, prognosis, treatment and aspects relating to hygiene and diet), information sources, accessibility to diagnostic tests, delays in diagnosis, patient strategies for coping with the symptoms, identification of reference professionals, integral care between healthcare levels, accessibility to clinical information and professionals, healthcare delays, coping with changes in family relations, friends and the occupational setting, and safe use of medicines. The group sessions were ended when information saturation was evidenced by similar or repetitive contributions on the part of the participants. Discourse analysis was made through reorganization of all the ideas of the participants in a script answering each of the key questions of the study, followed by classification of the ideas into mutually excluding categories -extracting examples from the discourse that unequivocally represented the meaning of each of these categories. This triangulation process was carried out by consensus among the authors JJM, MG and EIG. Analysis of the information for highlighting the salient ideas also considered the following: Within-group consistency, between-group consistency and relevance (considering the agreement observed among the participants).

Furthermore, all the participants (patients and professionals) individually scored the importance of a series of barriers against good care in patients with IBS, based on a scale from 0-5. This list of barriers was defined by consensus among the members of the research team. Such assessment on an ordinal scale was used to rank the relative position of the difficulties which in the opinion of the participants affected patients with IBS in key moments of the care process or in moments of transit between different healthcare levels. The coefficient of variation was included as a measure of consensus among the participants.

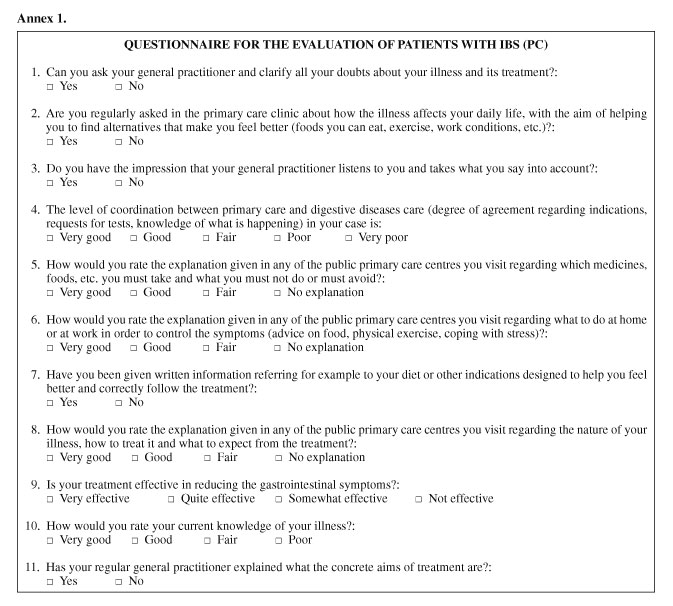

Based on the above information, we designed a series of questions for conducting structured interviews, and developed a scale for assessing patient opinion about the care received in the PC (14 items) and specialized digestive diseases setting (13 items) (Annex 1). Designing the scale involved the participation of 8 patients who scored comprehension of the questions and evaluated whether the questions explored relevant issues (apparent or face validity). In addition, a convenience sample of 33 patients with a profile similar to that of the patients participating in the focus groups was interviewed on an individual basis, answering the questions on the scales, following the obtainment of consent. The scales were available on the internet using the Survey Monkey application, in order to facilitate response and guarantee confidentiality. Principal components analysis, followed by varimax rotation, was used to determine the validity of the scales construct, with application of the Cronbach's alpha statistic to assess internal consistency.

The results of the interviews and scales included frequency (percentage) data to describe the experience of the patients with IBS. The chi-squared test was used to analyze the relationships between qualitative variables. The IBM SPSS Advanced Statistics 20.0 package was used throughout.

Results

A total of 60 patients and 10 professionals participated in the study.

Focus group results

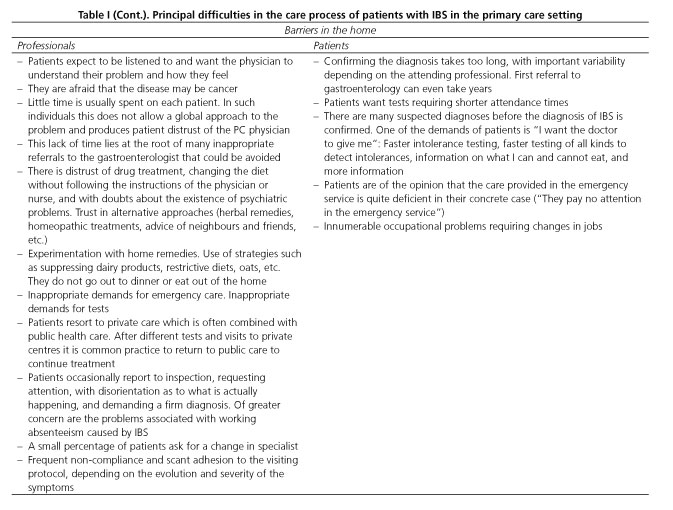

The main difficulties experienced by patients with IBS in their relationship with the healthcare system are (Table I): Accessibility of specialized gastroenterological consultation from the PC setting, with doubts regarding the capacity of the PC physician to identify the disorder, and fear that the disease may be serious (e.g., cancer); limited information on the probable course of the disease and on how it affects social and occupational life; incomprehension often due to insufficient information on the criteria used for referral to mental care; the briefness of visits in PC; and insufficient coordination between healthcare levels, reflected in patient perceived difficulties for receiving integral care.

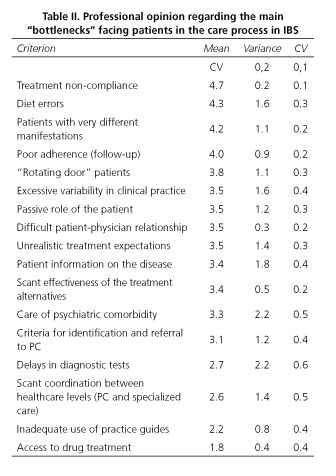

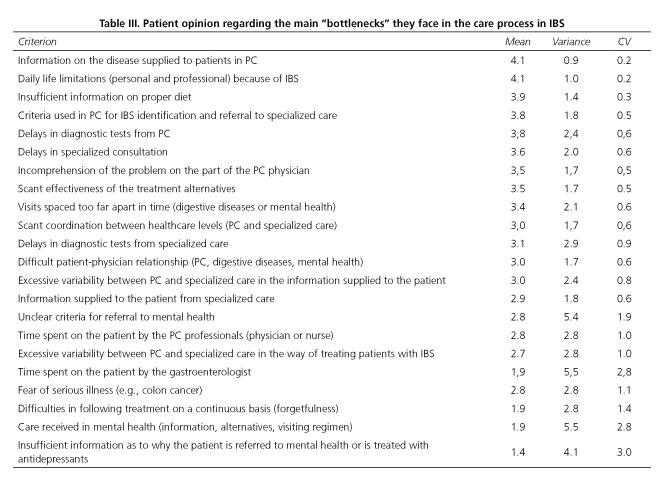

In turn, the professionals (Table II) emphasize that these patients are difficult to handle, because of low adherence to therapy and poor persistence with the management plan and follow-up. The main "bottlenecks" in the IBS management route for patients (Table III) are a lack of information on the disease -particularly as regards diet recommendations- and incomprehension on the part of the PC physicians, who sometimes take several months in establishing a first diagnosis.

In the opinion of the professionals, the different manifestations of IBS are one of the problems that account for the broad variability in the assessment and referral criteria used in such patients. For the patients, the day to day limitations are the main cause of concern, and in their opinion the existing treatment options are not always effective. The most common patient mistakes are related to continuous changes in eating habits.

Results of the interviews

Ten males (31%) and 23 females (69%) completed the interviews and care scoring scales. The mean patient age was 43.31 years. Twenty patients (62%) were working, though 17 (52%) had experienced problems at work because of the disease. In turn, 14 patients (44%) described their health as good or very good, while 8 (25%) considered their health to be poor. The most common symptoms at the time of response were: Lack of energy, tiredness (n = 14, 44%), fear of going out to have lunch or dinner (n = 11, 33%), abdominal pain (n = 9, 27%), diarrhoea (n = 9, 27%), libido loss (n = 9, 27%) and irritability (n = 7, 23%).

The items of the scale for PC focused on four factors (explanation of 73% of variance), while the scale for digestive disease focused on three factors (explanation of 67% of variance). The internal consistency was 0.84 and 0.82 for PC and digestive disease, respectively.

At the time of the interview, 12 patients (36%) regularly visited nursing care in PC, and 6 (18%) were attended in mental health in addition to being seen regularly in PC and digestive disease. Six patients (18%) combined public and private medical care.

The main source of information for knowing about IBS and how to deal with the disease was the gastroenterologist (n = 24, 73%), the PC physician (n = 10, 31%) and the internet (n = 7, 23%).

Twenty-two of the interviewed patients (67%) knew the indication of the prescribed medication and the dosing regimen. Fourteen (42%) claimed to have received instructions on what to do at home or at work to control the symptoms, together with advice on eating, physical exercise and coping with stress. Twenty patients (62%) agreed short- and middle-term treatment objectives with their physician. Thirty (40%) claimed to have received specific counselling from the physician on how to prepare for going out to dinner, and on the required precautions. In turn, 14 patients (42%) reported improvement with the treatment received, while four (12%) claimed to have stopped taking the medication because of tolerance problems or because it was regarded as ineffective.

The gastroenterologist was better rated than the PC physician in relation to the verbal information given on treatment alternatives (n = 21, 64% versus n = 9, 27%), accessibility for asking questions and clarifying doubts (n = 30, 91% versus n = 24, 73%), and the patient impression of having been listened to (n = 30, 91% versus n = 22, 67%). Twenty-nine patients (88%) claimed to be satisfied with the care received by the specialist in digestive diseases, while 24 patients (73%) claimed to be satisfied with the PC physician (chi-squared 2.4, p = 0.21).

Discussion

This study broadly examines the problems which patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) have with the primary care physician and specialist in digestive diseases, from the time of diagnosis and establishment of the treatment strategy, in the context of the Spanish public healthcare system. These are patients who are sceptical about the treatment received, and this scepticism is reinforced by having to undergo tests that yield no significant findings, changes in treatment in search of increased effectiveness, and unsatisfied expectations.

During the focus group sessions, and in line with the findings of other studies (20), the patients described the following principal problems related to the care process: Incomprehension and unresolved doubts on how to cope with the disease on a day to day basis. Specifically, the patients complained of delays in confirming the diagnosis (a problem that was found to decrease among patients under 35 years of age compared with earlier years, thanks to improved resolution capacity among PC physicians), unnecessary changes in the follow-up protocols once the diagnosis was established, and the quality of the relationship with the PC physician. In this regard, two groups were identified: Those patients who claimed to be trustful and considered that the PC physician understood their problems, and a second group expressing distrust of the capacity of the PC physician. The most demanded information was regarding the prognosis of the disease and the clarification of doubts referring to the diet and kinds of food that could be consumed. The patient findings were consistent with those of other studies in that more information was called for in order to overcome difficulties in the workplace, program leisure activities (21) and evaluate alternative medicine options (22). In the case of our healthcare system, such difficulties related to the patient-physician relationship were accompanied by delays in diagnostic tests as a further barrier facing patients in the care process associated to IBS. In contrast to other studies, our patients were reluctant to be referred to mental health units, complained of incomprehension if they reported to the emergency service, and expressed their preference for having a specialist in digestive diseases as reference physician. This study also considered the opinion of the professionals. A lack of adherence to therapy and persistence in the established follow-up protocol, along with constant changes and mistakes regarding eating habits on the part of the patients, were the factors that worried the professionals most.

In this regard, the interviews confirmed the data obtained in the first phase of the study, with 7 out of 10 patients having received enough information about their disease. These findings are very similar to those published by Ringström (23) in Sweden. However, the patients expressed a wish for more information regarding the diet and how it affects them, together with recommendations on how to cope with the symptoms in daily life (particularly at work), information related to the prognosis of the disease, and greater empathy and understanding on the part of the professionals. This data corroborates the findings of a study carried out in the United Kingdom (20) and in Boston in the United States (24), involving similar methodology. Self-care in IBS contributes to improve patient quality of life (25). This data is relevant, since it underscores the information shortcomings that make it difficult to implicate patients in their own care.

Patients do not want their symptoms to be trivialized, and call for greater treatment resolution in PC. This situation is similar to that found in other healthcare systems with organizational models similar to our own (19). According to the literature, one of the main problems is failure to adequately appreciate the patient discomfort, and this has a negative impact upon the patient-physician relationship, thereby complicating correct diagnosis and treatment (26,27).

The percentage of patients in this study who claimed to be satisfied with the care received was greater than the 13% satisfaction rate reported by Olafsdottir et al. (21). In this regard, the percentage of patients who claimed to be satisfied with the care received was more similar to that published by Drossman et al. (14). The data trend suggested slightly greater satisfaction with the gastroenterologist, though statistical significance was not reached. In this case the scale used was briefer and therefore easier to apply in the clinical context than the 38-item IBS-SAT (12), and the validity and consistency data were adequate in this respect.

The symptoms of the patients in our study were similar to those described in other publications (28). Nevertheless, the present study has some limitations. Although we attempted to ensure representation of the different patient profiles, the number of subjects was limited, in the same way as in most studies on IBS patient perception published to date. We did not codify age, gender or educational level for ensuring anonymity of the participants. Likewise, we did not contemplate access to the patient case histories. As a result, we did not have information on comorbidities, diagnostic tests or treatment. Since the patients had been attended in the PC setting at least 5 years ago, their assessments do not reflect the current state of primary care practice.

Patients with IBS question the resolution capacity of PC physicians and wish to receive more information on eating habits and on how to deal with the symptoms of their disease in the workplace. Future studies could determine whether the activation of these patients can contribute to reduce the characteristic symptoms of IBS.

In conclusion, our study summarizes the care problems found in IBS from the patient perspective. The incorporation of these data to the management of patients with IBS must be considered from both the individual clinical perspective (patient-physician relationship) and the organizational point of view.

Acknowledgements: This study would not have been possible without the voluntary and altruistic contribution of its participants.

References

1. Mearin F, Badia X, Balboa A, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome prevalence varies enormously depending on the employed diagnostic criteria: Comparison of Rome II versus previous criteria in a general population. Scand J Gastroenterol 2001;36:1155-61. [ Links ]

2. Peris F, Martínez E, Badia X, et al. Iatrogenic cost factors incorporating mild and moderate adverse events in the economic comparison of aceclofenac and other NSAIDs. Pharmacoeconomics 2001;19:779-90. [ Links ]

3. Almansa C, Rey E. The burden and management of patients with IBS: Results from a survey in Spanish gastroenterologists. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2011;103:570-5. [ Links ]

4. Halder SL, Locke GR, Talley NJ, et al. Impact of functional gastrointestinal disorders on health-related quality of life: A population-based case-control study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2004;19:233-42. [ Links ]

5. Faresjo A, Grodzinsky E, Johansson S, et al. A population-based case-control study of work and psychosocial problems in patients with irritable bowel syndrome - women are more seriously affected than men. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:371-9. [ Links ]

6. Ford AC, Forman D, Bailey AG, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome: A 10-yr natural history of symptoms and factors that influence consultation behavior. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:1229-39. [ Links ]

7. Johansson PA, Farup PG, Bracco A, et al. How does comorbidity affect cost of health care in patients with irritable bowel syndrome? A cohort study in general practice. BMC Gastroenterol 2010;10:31. [ Links ]

8. Di Palma JA, Herrera JL. The role of effective clinician-patient communication in the management of irritable bowel syndrome and chronic constipation. J Clin Gastroenterol 2012;46:748-51. [ Links ]

9. Levy S, Segev M, Reicher-Atir R, et al. Perceptions of gastroenterologists and patients regarding irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;26:40-6. doi:10.1097/MEG.0b013e328365ac70. [ Links ]

10. Harris LR, Roberts L. Treatments for irritable bowel syndrome: Patients' attitudes and acceptability. BMC Complement Altern Med 2008;19;8:65. [ Links ]

11. Denters MJ, Schreuder M, Depla AC, et al. Patients' perception of colonoscopy: Patients with inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome experience the largest burden. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;25:964-72. [ Links ]

12. Dorn SD, Morris CB, Schneck SE, et al. Development and validation of the irritable bowel syndrome satisfaction with care scale. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;9:1065-71.e1-2. [ Links ]

13. Drossman DA, Patrick DL, Whitehead WE, et al. Further validation of the IBS-QOL: A disease-specific quality-of-life questionnaire. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:999-1007. [ Links ]

14. Drossman D, Morris CB, Schneck S, et al. International survey of patients with IBS: Symptom features and their severity, health status, treatments, and risk taking to achieve clinical benefit. J Clin Gastroenterol 2009;43:541-50. [ Links ]

15. Halpert A, Godena E. Irritable bowel syndrome patients' perspectives on their relationships with healthcare providers. Scand J Gastroenterol 2011;46:823-30. [ Links ]

16. Black N. Patient reported outcome measures could help transform healthcare. BMJ. 2013;346:f167. [ Links ]

17. Black N, Varaganum M, Hutchings A. Relationship between patient reported experience (PREMs) and patient reported outcomes (PROMs) in elective surgery. BMJ Qual Saf 2014;0:1-9. [ Links ]

18. Mira JJ, Pérez-Jover V, Lorenzo S, et al. investigación cualitativa: una alternativa también válida. Atención Primaria 2004;34:161-9. [ Links ]

19. Mira JJ, Tomás O, Pérez-Jover V, Nebot C, et al. Predictors of patient satisfaction in surgery. Surgery 2009;145:536-41. [ Links ]

20. Jones R, Hunt C, Stevens R, et al. Management of common gastrointestinal disorders: Quality criteria based on patients' views and practice guidelines. British Journal of General Practice 2009;59:415-21. [ Links ]

21. Lacy BE, Weiser K, Noddin L, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome: Patients' attitudes, concerns and level of knowledge. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007;25:1329-41. [ Links ]

22. Harris LR, Roberts L. Treatments for irritable bowel syndrome: Patients' attitudes and acceptability. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2008;8:65. [ Links ]

23. Ringström G, Agerforz P, Lindh A, et al. What do patients with irritable bowel syndrome know about their disorder and how do they use their knowledge? Gastroenterol Nurs 2009;32:284-92. [ Links ]

24. Halpert A, Dalton CB, Palsson O, et al. What patients know about irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and what they would like to know. National Survey on Patient Educational Needs in IBS and development and validation of the Patient Educational Needs Questionnaire (PEQ). Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:1972-82. [ Links ]

25. Dorn S. Systematic review: Self-management support interventions for irritable bowel síndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010;32:513-21. [ Links ]

26. Rey E, Garcia-Alonso MO, Moreno-Ortega M, et al. Determinants of quality of life in irritable bowel syndrome. J Clin Gastroenterol 2008;42:1003-9. [ Links ]

27. Olafsdottir LB, Gudjonsson H, Jonsdottir HH, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome: Physicians' awareness and patients' experience. World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:3715-20. [ Links ]

28. Drossman D, Morris C, Schneck S, et al. International survey of patients with IBS: Symptom features and their severity, health status, treatments, and risk taking to achieve clinical benefit. J Clin Gastroenterol 2009;43:541-50. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Mercedes Guilabert.

Department of Health Psychology.

Universidad Miguel Hernández.

Avenida de la Universidad, s/n.

03202 Elche, Alicante. Spain

e-mail:

mguilabert@umh.es

Received: 12-10-2014

Accepted: 29-01-2015

texto en

texto en