Introduction

Pregnancy and having a baby are critical life-course stages for women, which is associated with substantial psychological and physical changes that prepare women for the challenges of motherhood (Dunkel-Schetter, 2011; Hoekzema et al., 2017; Hoekzema et al., 2020). Having a baby is a significant and possibly joyful time in life, but it also could be the most stressful transition for most women. In this sense, for many women having a baby can be a source of feelings of sadness that they find challenging to manage. These changes represent a vulnerable period to suffer mental health problems, with depression and anxiety being the most common.

Perinatal depression is an inclusive term for a spectrum of depressive conditions that can affect mothers during pregnancy and mothers up to twelve months postpartum. These depressive conditions include antenatal depression, postpartum depression, and postpartum psychosis (Gavin et al., 2005; Gelaye et al., 2016). Antenatal depression occurs during pregnancy, whereas postpartum depression occurs four weeks after delivery and even one year after delivery according to some authors (Yu et al., 2021).

Perinatal depression has been established as a major public health problem (Meaney, 2018; Miranda & Patel, 2005). Proper identification and treatment should be a priority for our healthcare system. Perinatal depression does not only affect the mother and her well-being with symptoms such as insomnia and irritability to loss of self, guilt, and shame. These symptoms can lead to an undermining of the mother's confidence, impair her social functioning, and reduce her quality of life, with repercussions for the baby as well. The consequences are not only related to psychological aspects or maternal and infant well-being. The literature has described how perinatal depression is associated with adverse perinatal outcomes, including increased risk of poor adherence to medical care, poor nutrition (inadequate or excessive gestational weight gain), loss of interpersonal and financial resources, and smoking and substance abuse with its attendant risks (Slomian et al., 2019).

Sometimes, barriers to treatment can appear in women due to lack of time, the associated stigma, or lack of knowledge about perinatal depression and its consequences, preventing them from seeking solutions to the situation they are experiencing (Bina & Glasser, 2019; Grissette et al., 2018). However, and this is more worrying, there are other institutional barriers such as lack of personal resources or inadequate training, lack of time for consultations, and simply lack of recognition of the problem by the health system that prevents women from receiving adequate treatment (Abrams et al., 2009; Prevatt & Desmasaris 2018), or suicidal attempts or ideations (Castelao et al, 2022).

Despite the prevalence and negative consequences, in our healthcare system this condition remains underdiagnosed and undertreated or treated below evidence-based standards. In response to this situation of lack of quality care in terms of assessment, prevention, and treatment, the General Council of Psychology of Spain convened a working group of experts in the field, including both academics and healthcare professionals, to review and propose recommendations based on evidence and best practices that can be applied. This group does not intend to establish new guidelines, but rather to systematize the existing ones and to call the attention of health managers so that this area does not continue to be under-diagnosed or under-treated.

Therefore, this consensus document aims, after reviewing the evidence, to establish the lines of action in the assessment, prevention, and treatment of perinatal depression, with special attention to the Spanish literature.

This document also pursues to promote the presence of the psychologist in the perinatal setting. Different professionals intervene in this period, though the presence of the psychologist is still merely anecdotal. These professionals should have specialized training in this field.

Finally, this document also aims to motivate an increase in research in this area in the Spanish context since, although it has increased in recent years, it is still scarce compared to other countries.

Method

This paper reports findings from a comprehensive narrative synthesis of previously published information on the topic of perinatal depression with special attention to what has been published in Spain.

A literature search focusing on perinatal depression was completed between 2000 and 2022 to identify relevant publications in this area.

The literature search utilized various databases (e.g., Medline, PsychInfo, and Google Scholar) using a combination of broad search terms, including peripartum depression (e.g., peripartum depression OR prepartum depression OR prenatal depression OR postpartum depression), AND diagnosis (e.g., diagnosis OR diagnostic criteria OR diagnostic tools), AND prevention (e.g., preventive interventions OR prevention OR prevention approaches), AND treatment (e.g., psychological treatment) AND (cost-effectiveness) AND (systematic review) AND (meta-analysis) AND (Clinical guidelines).

Prevalence

It is estimated that approximately one in five women develop a mental disorder during pregnancy and/or in the year following childbirth (National Childbirth Trust, 2017), with depression being the most common disorder (Dagher et al., 2021). Vulnerability to depression is increased in this period of a woman's life since childbirth is a life event associated with numerous biological, hormonal, psychological, familial, and social changes.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG, 2013) reports that depression is around 14-23% during gestation and 5-25% postpartum. Recent international data highlight prevalence rates of perinatal depression between 15-20% in the USA (Rafferty et al., 2019) and between 17-25% in China (Mu et al., 2019). A meta-analysis of the prevalence of perinatal depression in mainland China (Nisar et al., 2020), assessed by self-report scales, found it to be 16.3%, with antenatal depression at 19.7% and postpartum depression at 14.8%. An increasing trend in perinatal depression was also found in the last decade.

A meta-analysis of Japanese women (Tokumitsu et al., 2020) included studies in which depression was assessed by self-report. It was found that, during pregnancy, depression increased as the due date approached (14% in the second trimester and 16.3% in the third trimester), and decreased postpartum as time elapsed (14.3% at 1 month postpartum and 11.5% at 6-12 months postpartum). The prevalence of postpartum depression was higher in first-time mothers than in multiparous mothers with an adjusted relative risk of 1.76.

In a multicenter study conducted in Italy (Cena et al., 2021), where the prevalence of pre-and postnatal depression was assessed through the Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS), a prevalence of prenatal depression of 6.4% and 19.9% in the postpartum period was obtained. Importantly, they concluded that women with higher socioeconomic status were approximately five times less likely to develop prenatal depression and six times less likely to develop postpartum depression. This is in line with the finding regarding higher prevalence rates in developing countries relative to developed countries (Norhayati et al., 2015; Pereira et al., 2011).

Perinatal depression also affects other family members, not only women. A meta-analysis with data from 21 countries that assessed the presence of paternal perinatal depression (Rao et al., 2020) points out that perinatal depression is common among fathers as well. A prevalence of paternal depression was found to be 9.8% during a woman's pregnancy and 8.7% in the first year after delivery.

Antenatal Depression

In Spain, the prevalence of moderate and severe depressive symptoms during pregnancy was found to range from 14.8% (Rodríguez-Muñoz et al., 2019) to 15.2% (Marcos-Nájera et al., 2020) to 23.4% (Míguez & Vázquez, 2021a). Likewise, the prevalence differs according to the population studied, as the rate of antenatal depression is higher in immigrants, reaching 25.8% (Marcos-Nájera et al., 2020). In this regard, in a cross-cultural study conducted with women from Spain and Mexico (Marcos-Nájera et al., 2021), where the rates of antenatal depression were evaluated through the PHQ- 9 scale, a depression rate of 10% was found in Spanish women and 20.3% in Mexican women.

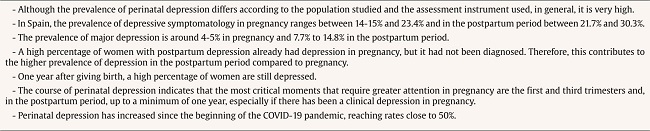

Regarding the trimesters with the highest prevalence, a longitudinal study conducted in our country (Míguez & Vázquez, 2021a) found a prevalence of depressive symptomatology, assessed with the EPDS, of 23.4% in the first trimester, 17% in the second trimester and 21.4% in the third trimester. Regarding the prevalence of major depression, this was 5.1%, 4.0%, and 4.7%, respectively. Thus, the prevalence of antenatal depression follows a V-shaped trajectory, with the highest levels being obtained in the first trimester, decreasing in the second trimester, and increasing in the third trimester, but without reaching the levels of the first trimester. (See Table 1).

Postpartum Depression

Postpartum depression is one of the most prevalent psychological disorders in women (Zivoder et al., 2019). One fact to note is that more than half of the women who suffer postpartum depression are not new cases, but have suffered depression in pregnancy that has not been detected and, consequently, has not received the necessary treatment and, therefore, they carry it into the postpartum period (Míguez et al., 2017). This leads to the fact that the prevalence of depression is usually higher in the puerperium than in pregnancy. Likewise, in first-time mothers, the percentage of postpartum depression is usually higher than in multiparous mothers and can reach rates of 35% (Kendall-Tackett, 2016).

Different studies in our country show that depressive symptomatology in the postpartum period is very high, being approximately between 26.7% (Besteiro et al., 2001) and 30.3% (Vázquez & Míguez, 2022). Regarding major depression, it ranges from 7.7% at 6 weeks postpartum (García-Esteve et al., 2014) to 14.8% at 1 year postpartum (Vázquez & Míguez, 2022). In a longitudinal study conducted throughout the first postpartum year (Vázquez & Míguez, 2022) depression was assessed at three-time points: 2 months, 6 months, and 1 year postpartum. The prevalence of depressive symptomatology assessed with the EPDS was 30.3%, 26.0%, and 25.3%, respectively, and that of major depression was 10.3%, 10.9%, and 14.8%, respectively. Thus, throughout the postpartum year, the prevalence of depressive symptomatology was highest at 2 months and followed a downward trajectory, although it remained very high, and that of major depression was highest at 1 year postpartum and followed an upward trajectory.

Perinatal Depression and COVID 19

Several studies have focused on exploring how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected the mental health of pregnant women. Concerning perinatal depression, an increase in rates has been found, as can be seen in two studies carried out in our country. In a cross-sectional study, the impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of pregnant and puerperal women (whose children were less than 6 months old) was evaluated through self-report scales (Perinatal Experiences of Coronavirus COPE-IS; Thomason et al., 2020) and the EPDS (Cox, 1994). A perinatal depression rate of 47.2% was found (Motrico, Domínguez-Salas, et al., 2022). In another study, Chaves et al. (2022) evaluated a sample of women at the time of gestation and after delivery. Depressive symptoms were reported by 58% of women.

Risk Factors and Comorbidity

Risk factors are those variables, characteristics, behaviors, or conditions that are associated with a higher probability of occurrence of a disease or health problem (Giannini et al., 2012). In the field of perinatal mental health, this means exploring which biopsychosocial factors may increase the rates of occurrence of certain mental disorders, the most common being emotional disorders (depressive, anxious, and related disorders), although problems such as substance abuse (alcohol or other drugs) and psychosis, among others, are also included (Howard & Khalifeh, 2020; Johnson et al., 2012).

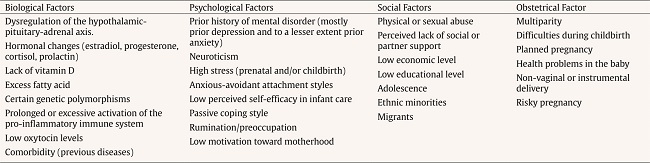

Currently, we have recent literature reviews on risk factors for perinatal mental health (Baron et al., 2017; Hutchens & Kearney, 2020; Míguez & Vazquez, 2021b; Yang et al., 2022), including in specific populations such as adolescent mothers (Recto & Champion, 2017) or military women (Klaman & Turner, 2016). In general, the first thing that different studies highlight in this regard is that the best predictor of depression at any time during the perinatal stage is the existence of previous and recent depressive symptomatology (Hutchens & Kearney, 2020). This points to the importance of an early assessment during the prenatal stage and detection that allows the implementation of secondary prevention programs that avoid the worsening of symptoms and thus minimize their consequences. The support of new information technologies will be key in this endeavor (Martínez-Borba et al., 2018).

In addition to a previous and recent history of mental health problems, review studies have evidenced that perinatal depression is particularly affected by the existence of physical or sexual abuse, for example in the form of male violence, whether current or previous (Van Niel & Payne, 2020). Studies suggest that male violence and previous and recent history of mental disorders could increase the probability of suffering perinatal depression problems by a factor of five (Yang et al., 2022).

Other biopsychosocial variables associated with increased likelihood of experiencing perinatal depression are health problems in the baby, a non-vaginal or instrumented delivery (Dekel et al., 2019), lack of social support (Racine et al., 2020), marital dissatisfaction (Whisman et al., 2011), low socioeconomic and educational status, ethnic minority background, high psychological, and biological stress (Glover et al., 2010; Lobel et al., 2022), high neuroticism (Martín-Santos et al., 2012), tendency to excessive rumination and worry (Osborne et al., 2021; Petrošanec et al., 2022), high perfectionism (Maia et al., 2012), anxious/insecure attachment styles and passive coping (Gutiérrez-Zotes et al., 2015; Warfa et al., 2014), such as a tendency to self-blame and distractibility and difficulty reframing problems in a positive way (Gutiérrez-Zotes et al., 2016), low self- and partner motivation to have a baby (Reut & Kanat-Maymon, 2018), the existence of a substance abuse disorder (Chapman & Wu, 2013), family history of depressive or anxiety disorders, or the experience of multiple, unwanted, particularly difficult or adolescent childbirth (Hutchens & Kearney, 2020; Meuti et al., 2015; Puyané et al., 2022; Soto-Balbuena et al., 2018;Van Niel & Payne, 2020). In the case of adolescent females, in addition, family criticism, self-esteem, and perceived self-efficacy seem to become particularly important (Recto & Champion, 2017).

Another variable is ambivalence towards motherhood, understood as the coexistence of positive and negative feelings associated with being a mother (Martín-Sánchez et al., 2022), which has been traditionally silenced in this field and has been shown to play an important role in predicting a worsening of symptoms throughout the perinatal stage (Santos et al., 2017).

Another population at particular risk for perinatal mental health problems, such as depression and perinatal post-traumatic stress disorder, are migrant women who have approximately twice the risk of suffering depression than non-migrant mothers (Anderson et al., 2017). It seems that poor social support, lack of competence in the language of the host country, low socioeconomic status, refugee or asylum seeker status, and belonging to minority ethnicities would be some variables related to the occurrence of these disorders (Chrzan-Dtko, et al., 2022). This may be particularly relevant in Spain given the increasing multiculturalism of this country due to different migratory movements experienced in recent decades (Ledoux et al., 2018; Martínez-Herreros et al., 2022).

Review studies more focused on biological aspects also point to variables such as a dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, lack of vitamin D, excess fatty acid, some genetic polymorphisms, and prolonged, excessive activation of the proinflammatory immune system visible in levels of the cytokine interleukin IL-6 or low levels of oxytocin as risk factors for perinatal depression (Serati et al., 2016; Thul et al., 2020).

Regarding the difference between prenatal and postpartum risk factors, the key seems to lie in the fact that, in the latter, factors related to complications during delivery and infant health characteristics may appear in the equation, as described above, although we would not find major differences in other aspects (Martinez-Borba et al., 2020; Silverman et al., 2017).

The studies carried out in our country point in the same direction as the systematic reviews referenced in the previous lines, with depression during pregnancy being the best predictor of postpartum depression in different studies (Marín-Morales et al., 2018; Martínez-Borba et al., 2020). Furthermore, the association between the personality trait of neuroticism and postpartum depression (Marín-Morales et al., 2014) and the importance of comorbidity between anxiety and depression (Peñacoba-Puente et al., 2016) are also confirmed. Also in our context, it has been shown that being an immigrant increases the risk of suffering perinatal depression problems (Marcos-Nájera et al., 2020).

In summary, as shown in Table 2, the literature has already evidenced numerous risk factors for perinatal depression, with a previous history of psychopathology and physical and sexual abuse being the factors that have received the most support and would play the most important role.

Diagnostic-Assessment Tools

Several national and international organizations have recognized the importance of routine screening of the population in this period. Thus, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG, 2013) has published reviews in which they recognize the benefits of screening and recommend that it be performed along with other obstetric tests during the gestational period. In the same vein, the American Academy of Pediatrics also upholds the need for population screening in the postpartum period (Earls et al., 2019). The Task Force and NICE Guidelines similarly pick up on the need to establish good population screening (O'Connor, 2016; NICE, 2014). A recent systematic review of Clinical Guidelines on postpartum depression indicates that, out of a total of fourteen guidelines analyzed, ten include specific recommendations on screening in this population (Motrico, Moreno-Peral, et al., 2022).

In Spain, although tangentially, the Clinical Practice Guideline on Pregnancy and puerperium care (Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad [MSSSI, 2014]) also includes the importance of establishing follow-ups related to maternal mental health.

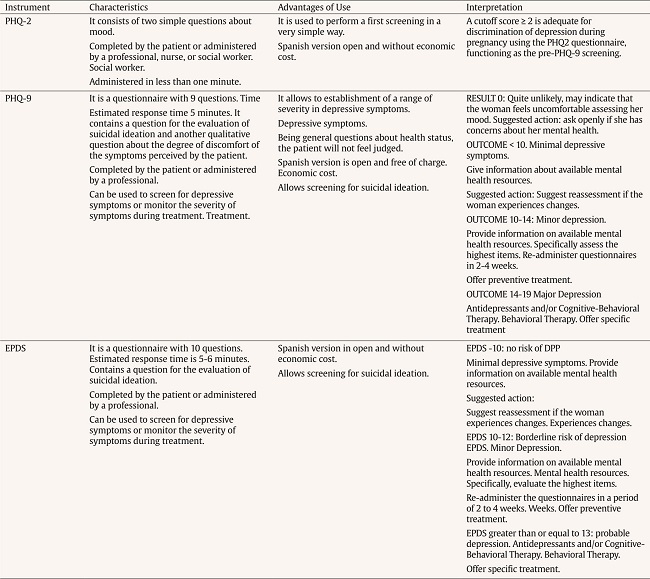

All these recommendations point to the need to use, in primary care settings, validated screening tools, including the PHQ-2 (Kroenke et al., 2003), the PHQ-9 (Kroenke & Spitzer, 2002; Manea et al., 2015), and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; Cox et al., 1987). Indeed, the literature argues that both obstetric (Rodríguez-Muñoz et al., 2017) and pediatric (Earls et al., 2019) settings may be appropriate venues for the establishment of routine screenings. These screenings would allow the detection of cases that should subsequently be evaluated with a clinical interview that would allow the establishment of an accurate diagnosis and, if necessary, intervention. The proposal for the screening of the perinatal population, included in this document, focuses on those questionnaires that have demonstrated good psychometric properties in Spanish samples. (See Table 3).

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke & Spitzer, 2002; Manea et al., 2015)

This questionnaire is used to assess depressive symptomatology and prevalence of antenatal depression (+; Kendig et al., 2017). The PHQ-9 is validated with Spanish-speaking populations and Spanish-pregnant women (Marcos-Nájera et al., 2018). Its nine items are based on the criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Disorders-5 (American Psychiatric Association [APA, 2013]). Responses are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale, where 0 is no day and 4 is almost every day. The PHQ-9 has good psychometric properties (Kroenker & Spritezer, 2002) good internal consistency and general health status questions patients report not feeling judged.

Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2; Kroenke et al., 2003)

Consisting of only two questions, this questionnaire has been proposed by the NICE Guideline (MSSSI, 2014) as the first screening instrument in this population. There is a study in Spain, adapted to the Spanish pregnant population (Rodríguez-Muñoz et al., 2017), which demonstrates the good properties of the questionnaire. Depending on the results obtained, if the score obtained is higher than the point established for the Spanish population, the PHQ-9 questionnaire (see Table 3) or the interview should be administered to be able to establish a more precise conclusion about the presence or not of depressive symptoms.

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; Cox et al., 1987)

This is the most widely used self-report scale to identify in women the risk of perinatal depression (Cox, 2019). The scale consists of 10 items that assess how women have been feeling during the previous week. Responses are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale, where 0 is no day and 4 is almost every day. This questionnaire has good psychometric properties (Cox & Holden, 1994). The EPDS scale has obtained good psychometric properties in Spanish samples both in pregnancy (Vázquez & Míguez, 2019) and postpartum (García-Esteve et al., 2003).

The EPDS includes anxiety symptoms, but excludes constitutional symptoms of depression, such as changes in sleep patterns, which may be common in pregnancy and postpartum and which could establish, if not adequately screened for, a higher number of false positives.

In any case, it should be emphasized that symptom screening is never a diagnosis and should be performed by a mental health professional. The European Clinical Guidelines (Motrico, Moreno-Peral, et al., 2022) also emphasize the need for diagnosis. Thus, of the fourteen guidelines collected in the study, eight establish diagnostic systems in the perinatal population.

The main objective of the assessment by the mental health professional is to make an exploration of the patient's psychological state. As secondary objectives, the aim is to identify risk and protective variables for the management of maternity as well as to begin to develop the therapeutic link.

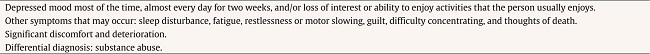

In the exploration, it is important to assess at what point in the perinatal period (pregnancy or postpartum) the presence of symptoms begins. The DSM5-TR (APA, 2022) includes it with the specificity “postpartum onset or peripartum onset” if the symptoms began during pregnancy or within 4 weeks after delivery. It is important to make a proper differential diagnosis concerning brief psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. It should not be forgotten that in the immediate postpartum period, the main differential diagnosis is postpartum sadness or melancholy (Rezaie-Keikhaie et al., 2020).

In mood episodes, it is very important to explore the history of depressive symptoms. We also know about the high comorbidity with an anxious clinic, especially of anxiety crises (Falah-Hassani et al., 2017), so it would be important to explore it at present and history. (See Table 4). Psychotic clinic may present within an anxious episode or psychotic process.

In addition to exploring the aforementioned disorders, it is also important to differentiate this diagnosis from organic processes such as metabolic alterations of the thyroid hormone (Bourget et al., 2007), changes in neurotransmitters (Vahdat et al, 2007), or iron deficiency that causes depressive symptoms and hyperactivity (Murray-Kolb & Beard, 2009).

As we pointed out, it would be advisable to also perform an assessment of risk and protective variables, which can help us in the diagnosis and future intervention. Table 2 presented in section 4 of this document can be a reference for such an assessment

Prevention

Preventive interventions in perinatal mental health are aimed at reducing risk factors and promoting protective factors in women without a diagnosis of perinatal depression, to reduce the incidence or onset of the mental health problem globally (Arango et al., 2018).

Prevention programs are classified into three types according to the type of population served: universal, selective, and indicated. First, universal prevention refers to programs focused on all women in the perinatal period regardless of whether or not they present risk factors for perinatal depression. Second, selective prevention programs narrow their focus to the more specific sector of women who, because of their characteristics or behaviors, would be more likely to develop perinatal depression. Third, indicated prevention programs focus on women who present symptoms but are in a subclinical state, therefore do not yet meet the criteria for a diagnosis of perinatal depression (Arango et al., 2018).

Universal Prevention

A holistic intervention that includes aspects of physical health and mental health during pregnancy and postpartum may be most appropriate within universal prevention programs for perinatal depression. Evidence suggests that promoting healthy lifestyles, especially physical exercise, can have positive effects on perinatal depression (Carter et al, 2019; McCurdy et al, 2017). In addition, psychoeducational interventions, including general pregnancy information, birth plan, and childbearing (adjusting expectations, working through myths, checking questions and answers, clarifying concepts), are advised for all mothers and their partners in the perinatal period. Evidence is also demonstrated for interventions that target the promotion of both emotional and instrumental social support (Dennis & Dowswell, 2013).

Selective and Indicated Prevention

Selective prevention is that which focuses on women who present psychosocial risk factors for perinatal depression in the perinatal context. It is recommended that at least the following risk factors be assessed: history of depression, anxiety symptoms, low socioeconomic status, teenage pregnancy, intimate partner violence, and the accumulation of stressful life events (Curry et al, 2019). These risk factors can be assessed with a clinical interview or standardized questionnaires such as the Postpartum Depression Predictors Inventory-Revised (PDPI-R; Rodríguez-Muñoz et al., 2017).

On the other hand, indicated prevention refers to women who experience depressive symptoms without meeting the criteria for a diagnosis of perinatal depression. Having symptoms of depression is in itself a risk factor for perinatal depression, so the evidence tends to recommend the same type of programs for both groups. In this sense, the studies conducted to date indicate that in those pregnant women who present risk factors and/or symptoms of depression, the application of psychological interventions is recommended, specifically cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and interpersonal therapy (IPT) (Curry et al, 2019; Rodríguez-Muñoz et al., 2021). Secondly, the application of psychosocial interventions, either at the individual or group level, is recommended during pregnancy and puerperium (Dennis & Dowswell, 2013).

In Spain, we have pioneering studies on the prevention of perinatal depression. Le et al. (2020) found that the “Moms and Babies” program was effective for the prevention of depression in pregnant women with risk factors at 3 and 6 months postpartum. This study collects the results of the cultural adaptation of the “Moms and Babies” program to the Spanish reality.

Treatment

Effective treatments for postpartum depression are essential for the public health system. Today there are empirically validated pharmacological and empirically validated psychological interventions for its treatment (O'Hara et al., 2015). The number of randomized controlled trials testing interventions has greatly increased since the 1990s. However, many women with perinatal depression do not receive proper treatment. This is due, in part, to difficulties in accessing mental health specialists and, in many cases, the absence of psychological measures in routine screening protocols in early care (Rodríguez-Muñoz et al., 2019).

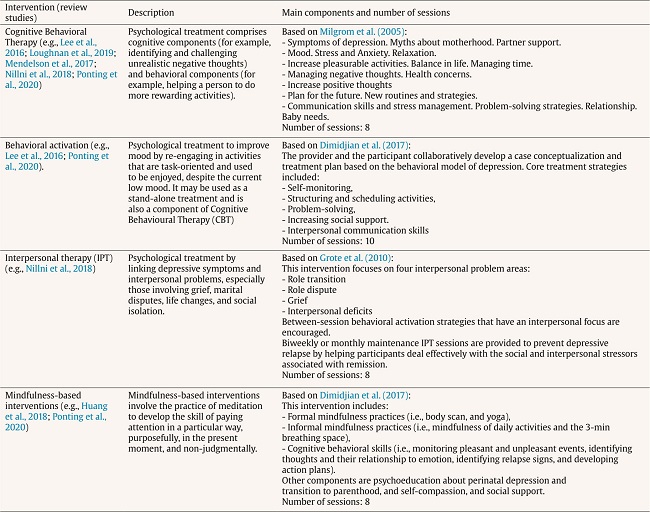

NICE (2014) guidelines emphasize the use of therapy in those patients with a previous history of depression or with moderate or severe levels. On the other hand, a recent review of clinical guidelines (Motrico, Moreno-Peral, et al., 2022) highlights how, out of 14 European guidelines on postpartum depression, 10 include information on psychological interventions. (See Table 5). Along the same lines, several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have endorsed the efficacy of psychological treatments to reduce symptoms of depression both prenatally and in the postpartum period (Branquinho et al., 2021; Cuijpers et al., 2021). These psychological interventions span approaches from CBT, behavioral activation (e.g., Lee et al., 2016; Ponting et al., 2020), IPT (e.g., Nillni et al., 2018), mindfulness-based interventions (e.g., Huang et al., 2018; Ponting et al., 2020), psychological or social support (e.g., Mendelson et al., 2017), and psychoeducation or education-based interventions (e.g., Nair et al., 2018). Overall, these interventions have shown a moderate to large effect (Cuijpers et al., 2021). Their results are positive in the short and long term (6-month follow-up). CBT has been shown to be the most effective intervention regardless of its type (e.g., individual vs. group; face-to-face vs. telematic) (Branquinho et al., 2021). CBT is included in evidence-based treatment guidelines as the first line of treatment for perinatal depression (NICE, 2014). In addition, the US Preventive Services Task Force in its review of more than 470 studies shows that the application of CBT in women with pre- and postpartum depression detected by screening represents a significant increase in the likelihood of referral compared to usual care, with absolute increases ranging from 6.2% to 34.6% (O'Connor et al., 2016). IPT has been shown to be effective to reduce perinatal depression although these results are inconsistent. It should be noted that contextual or third-generation behavioral interventions (e.g., mindfulness-based, compassion, ACT) have shown promising results, although there is not yet sufficient evidence on their efficacy for perinatal depression. Therefore, it is still early to compare their results with those of other widely used treatments, such as CBT or IPT (Branquinho et al., 2021). All these works have in common the inclusion of content on the mother-baby dyad, psychoeducation on postpartum depression, interpersonal communication skills, or the increase of pleasant activities or positive thoughts. Regarding the format of psychological interventions, different formats have been found effective (internet-delivered or face-to-face, individual or group) (Branquinho et al., 2021) Also it is important to note that a follow-up session has been highlighted as part of the intervention. The application of the treatment for perinatal depression must take into account the specific difficulties of this period. Women tend to have difficulties in attending sessions related to practical aspects (breastfeeding, mobility problems, etc.).

Regarding the most current proposals, we highlight the use of transdiagnostic psychological interventions, where the Unified Protocol (Barlow et al., 2018) for the treatment of perinatal anxious and depressive symptoms or disorders stands out. This CBT-based intervention focuses on the training of adaptive emotional regulation skills. Spain has been a pioneer in this line with the realization of the first adaptation of the Unified Protocol for the treatment of a case of perinatal depression (Crespo-Delgado et al., 2020). In the coming years, randomized clinical trials will be developed applying the Unified Protocol for the prevention and treatment of emotional disorders.

A Multidisciplinary Treatment

In relationship with pharmacological treatments, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the most prescribed (Brown et al., 2021; Kittel-Schneider et al., 2022; Wisner et al., 2006), although it should be pointed out that their efficacy depends to a large extent on adherence to treatment. There are still only a few randomized controlled trials on the use of antidepressants in the perinatal stage. Considering the lack of knowledge about the efficacy and safety of antidepressants during the prenatal stage and lactation and the concern about the effects that medication may have on the fetus or its infants during breastfeeding (Kim et al., 2011), pharmacotherapy is usually reserved for more severe cases (O'Hara et al., 2015). Likewise, it is important to highlight how psychological treatment is the treatment preferred by women in this period since they understand that it will not have side effects for the fetus or breastfeeding. It is for this reason that psychological interventions are the treatment of choice for many women in the perinatal stage, especially those with a first episode of depression (O'Connor et al., 2016). Therefore, it is essential to emphasize the need for psychology professionals specialized in the field. Coordination with other professionals (obstetricians, midwives, nursing staff, or primary care physicians) is a basic issue, but this should not make us forget that it is the psychologist who must perform the psychological interventions.

Cost-effectiveness

Despite the existence of effective psychological treatments for the management of perinatal depression, only about 10-15% of women have access to them (Gavin et al., 2005; Goodman & Tyer-Viola, 2010; Woolhouse et al., 2009). This situation, untreated maternal depression, results in a severe impact on the mother (e.g., chronification of symptoms, risk of suicide, loss of productivity, and decreased quality of life) and on the fetus/baby (e.g., premature delivery, increased pediatrician visits or increased hospital emergency department visits, emotional problems, behavioral problems, or poor school performance), which in turn translates into high economic costs for health and social care systems (Bauer et al., 2014). For example, in the United Kingdom (UK) the estimated total cost of a single case of PPD is around £74,000, where £23,000 relates to the mother and £51,000 related to adverse effects on the child (Bauer et al., 2014). Nevertheless, in Spain there are no studies on the topic and therefore the actual cost within the health care system is unknown.

Some recent studies show how psychological care offered during pregnancy and postpartum to vulnerable women significantly reduces the economic cost to health systems (Franta et al., 2022). Although more research is needed in this regard, as there is great heterogeneity in cost-effectiveness studies in the treatment of perinatal depression (Camacho & Shields, 2018), it seems clear that maternal mental health care offers great benefits both at the personal level and at the social and community levels. This is why having or providing specialized services for this population (both for prevention and treatment) within health systems is recommended.

Conclusions

Perinatal depression is a problem of global importance, with negative repercussions on the woman herself, the baby, family dynamics, and society (Slomian et al., 2019; Organización Mundial de la Salud [OMS, 2018]). This makes its identification and treatment a public health priority (Meaney, 2018). However, there are barriers to diagnosis and treatment such as women's lack of time, associated stigma, lack of knowledge about PPD, and lack of personal resources, training, or time in the consultation among others, which prevent providing quality care in the perinatal period. It is necessary to systematize the existing guidelines and establish lines of action in the evaluation, prevention, and treatment of PPD. In contrast to all the work published on perinatal depression in the Anglo-Saxon context, in which screening and treatment of the population are promoted, in Spain it is still a problem that is underdiagnosed and undertreated. There is also the problem of the scarce presence of psychology professionals in Spain in this area.

The narrative synthesis of this work compiled the results of previously published information on the subject of perinatal depression. It is described that approximately one in five women develops PPD (National Childbirth Trust, 2017), in turn, this disorder also appears in men, although the prevalence is lower, around 9% (Rao et al., 2020). Specifically in Spain, in women a prevalence of around 15% is observed in the antenatal period (Rodríguez-Muñoz et al., 2017), being higher in the first and third trimesters (Míguez & Vázquez, 2021a) and around 27% in the postnatal period (Besteiro et al., 2001), in which many of the cases are untreated depression in pregnancy. At two months postpartum, it seems to be the time of highest prevalence and decreases over time, except for cases of major depression which follows an upward trajectory (Vázquez & Míguez, 2022). After the pandemic caused by COVID-19, these figures have increased, reaching a prevalence of 47% (Motrico, Domínguez-Salas, et al., 2022).

Among the related risk factors, mental health history (Hutchens & Kearney, 2020) and the existence of current or previous physical or sexual abuse (Van Niel & Payne, 2020) stand out as the best predictors. Numerous studies have been conducted to detect risk factors related to the development of PPD, offering a multidimensional picture of perinatal depression, which is influenced by biological, psychological, social, and obstetric factors. Thus highlighting the relevance of a biopsychosocial approach and the need to evaluate in this period, a task for which new information and communication technologies could be a key tool (Martínez-Borba et al., 2018).

It has been proposed to assess as part of routine consultations during this period (ACOG, 2018), in that way to obtain a follow-up of maternal mental health (MSSSI, 2014) and an adequate screening. For this, the most relevant tools in the Spanish version would be the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Marcos-Nájera et al., 2018), the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2; Rodríguez-Muñoz et al., 2017), and the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; García-Estévez et al., 2003).

For its prevention, the aims of the interventions are to promote protective factors and reduce risk factors in women without a diagnosis of perinatal depression.

Firstly, universal prevention, aimed at all women in the perinatal period, would focus on promoting mental well-being through healthy lifestyles, psychoeducational interventions, especially focused on providing information and working on expectations about this stage, and interventions to promote socio-emotional support. Secondly, selective and indicated prevention focuses on women who are more vulnerable to the development of perinatal depression because they present risk factors or subclinical symptoms of depression. Psychological, CBT or IPT and psychosocial interventions are recommended for these women.

In terms of treatment, despite the availability of empirically validated psychological and pharmacological interventions for the treatment of perinatal depression, there are difficulties in accessing them, mainly due to the lack of human and material resources, due to the lack of early care screening protocols with the measurement of psychological variables, as well as difficulties in accessing mental health specialists.

In patients with a previous history of depression, psychological therapies are emphasized. Psychological treatments are effective in reducing pre- and postnatal depressive symptoms. The main psychological interventions are cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), interpersonal therapy (IPT), behavioral activation, mindfulness-based interventions, psychoeducational interventions, and psychological and social support. Of these, CBT is the first line of treatment for perinatal depression and has shown efficacy regardless of the format of application. Third-generation therapies are showing promising results but there is insufficient evidence for their application in perinatal depression.

The most effective therapies for clinical perinatal depression have the following common characteristics:

They include content on the mother-baby relationship.

Psychoeducation on postpartum depression.

Encouraging positive thinking and pleasurable activities.

Interpersonal communication skills.

Increased social support.

Increased maternal self-efficacy.

A follow-up session should be added to promote the effectiveness of the intervention. For the implementation of the treatment of perinatal depression, the peculiarities of this stage should be taken into account and adapted to them.

Untreated perinatal depression can have negative consequences on both mother and baby, as well as producing high health and social expenditure. As has been seen throughout the document, there are effective psychological treatments to address perinatal depression, but these reach a very small percentage of women (between 10-15%). Offering psychological care in the perinatal stage to vulnerable women has shown that it translates into significant economic savings for health systems. Therefore, it can be concluded that, although more studies are needed in this area, offering specialized maternal mental health care is beneficial at a personal, social, and community level.

All this evidence suggests that it is necessary to include psychological aspects in the perinatal period as another aspect of care. In our country, there are already experiences (Generalitat de Catalunya, 2018), both in the public health system and in private practice, of assistance in the perinatal period where psychological aspects are included. Likewise, at the academic level in recent years, a sufficient body of knowledge has been generated that allows us to know evidence related to the concept that concerns us, adapted to our sociocultural environment. However, despite these initiatives, there is still no systematized and widespread practice throughout the country with routine evaluations that would allow referrals to specialized professionals in the field. As has been pointed out in previous pages, not intervening has a high cost, both at an emotional level due to the consequences it generates, as well as costs in economic terms for the health system. For this reason, and at the request of the General Council of Psychology, with the collaboration of both academic and healthcare experts, this document has been prepared. It is time to place psychology in Spain in the perinatal period. To this end, as final recommendations, we advocate the following:

Establishment of mandatory screening protocols in all Autonomous Communities, at least once during pregnancy, and at least once again in the postpartum period.

Inclusion in maternal education of programs for the promotion of mental wellbeing and selective/indicated prevention carried out by a psychology professional with specialized training in the area.

Inclusion of contents in the field of reproductive and perinatal mental health in the training programs of the General Health Psychologist and Psychology and Psychiatry Residents.

Implementation of programs and/or specialized Perinatal Mental Health units in which a psychology professional is included.