Introduction

Medication errors (ME) are important contributors to patient morbidity and mortality, and are associated with inadequate patient safety measures1. The severity of an ME can be graded according to its impact on the patient and/or its potential future risk to patients and the healthcare organization. This approach has the advantage that it can classify and analyse the severity of MEs that pass unnoticed because they have no effect on the patient. Moreover, this type of assessment is useful for prioritizing cases that require special monitoring, analysis, or urgent solutions2.

The National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) designed a risk matrix for grading MEs according to their potential future risk to patients and the healthcare organization. This matrix has two categories: likelihood of recurrence; and most likely consequences. However, details were not provided on the criteria by which a specific type of ME is classified according to its likelihood of recurrence and consequences3. Thus, the lack of definition allows room for subjectivity and researchers will interpret the risk matrix according to their knowledge and expertise4.

Subjectivity can be reduced by standardizing the classification of the potential risk of an ME. In a previous article, we adapted the NPSA risk matrix to medication errors in medication administration records (ME-MAR). The definition of each grade of the likelihood of ME-MAR recurrence was based on the incidence of ME-MAR in our hospital, and that of the most likely consequences was based on the type of ME-MAR and the medication involved. We found that this adaptation was reliable. However, during this process, the degree of agreement differed according to the medication involved in the error. The highest degree of agreement was achieved on high-risk medications5.

All medications can cause adverse events if they are incorrectly used. Nonetheless, certain medications are more dangerous than others and can have very severe or even catastrophic effects on patient health6. The Institute of Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) has provided a list of high-risk medications in hospitals7,8. However, lists of low-and medium-risk medications are not available. The hospital pharmacotherapeutic guide (HPG) not only includes high-risk medications but also unclassified medications, which may range from low to high risk. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to stratify medications in the HPG according to their potential risk.

Methods

The study was conducted between October 2015 and March 2016 in a 947-bed teaching hospital. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method (RAM)9,10 was used to stratify medications in the HPG according to their potential risk. The medications included in the HPG are classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system11 , and so the medications were evaluated per ATC subgroup.

The first step in the RAM was to identify scenarios, which were subsequently assessed by an expert panel in 2 consecutive rounds.

Information search and development of scenarios

In order to develop the scenarios (i.e., the stratification of the ATC subgroups according their potential risk), we conducted a review of MedLine publications (October 2005 to October 2015) on medications and their potential risk to inpatients. The search was restricted to the English and Spanish languages (see search strategy in Table 1). We selected studies that stratify medication risk or those that meet the following criteria: a) contain information on incidents caused by the clinical use of medications; b) report the number or percentage of incidents associated with each different medication /medication class, or provide sufficient information to calculate the number or percentage; and c) report the severity or the potential risk of these incidents.

This information was supplemented by searching the websites of safety organizations for bulletins and alerts referring to severe MEs12-15, by consulting recent drug information16,17, and by reviewing high-alert medications lists published for hospitals by the ISMP 8.

Expert panel selection

The panel was selected according to the following criteria: a) expertise in medication and patient safety and management; b) expertise in medication use process (physicians, pharmacists, and nurses).

The panel comprised 9 experts: 3 physicians (a geriatrician, an internist, and a pharmacologist); 3 hospital pharmacists with clinical experience in geriatrics, paediatrics and rheumatology, and intensive medicine, respectively; and 3 nurses (the inpatient care chief nurse, the emergency department nurse manager, and the traumatology department nurse manager).

Expert panel evaluation

The experts participated in two consecutive evaluation rounds. In the first round, they received the following documents by email: the identified scenarios, the evidence-based summary, the definitions of terms, and instructions for rating.

The experts were asked to assess the appropriateness of the ATC subgroup to the assigned scenario. Their appropriateness was rated on a 9-point scale, where 1 indicated “completely inappropriate” and 9 indicated “completely appropriate”. Agreement was defined as no more than 2 panel members rating the indicator as being outside the same 3-point region as the observed median (i.e., 1-3, 4-6, 7-9). The median panel rating and interquartile range were calculated. Any median ratings that fell exactly between the 3-point boundaries (3.5 and 6.5) were included in the higher appropriateness category.

ATC subgroups with a median rating in the top third of the scale (7-9) without disagreement were classified as appropriate, those with intermediate median ratings (4-6) or any median with disagreement were classified as uncertain, and those with median ratings in the bottom third (1-3) without disagreement were classified as inappropriate.

The second round comprised a face-to-face meeting during which the results of the first round were presented. Each panel member received an individualized evaluation questionnaire with the panellist’s own rating from round one, the overall panel median rating from round one, and the anonymised frequency distribution of the ratings for purposes of comparison. During the meeting, the moderator introduced the ATC subgroups that had been classified as inappropriate or uncertain during round one. The experts discussed each of these ATC subgroups with the option of changing the assigned scenario. Changes were made by panel consensus. Finally, the members individually and anonymously reevaluated the ATC subgroups. The results obtained from the second round were analysed and classified using the same methods as those used in the first round.

Results

Review of information and definition of scenarios

A total of 593 articles were reviewed, of which 38 were initially selected based on the title and abstract screening. After reviewing the full text of the articles, 19 were finally selected. The main reasons for exclusion were not reporting the number or percentage of incidents associated with each medication (n = 8), not reporting the severity or the potential risk of the incidents associated with each medication /medication class (n = 7), or not including in-hospital events (n = 4).

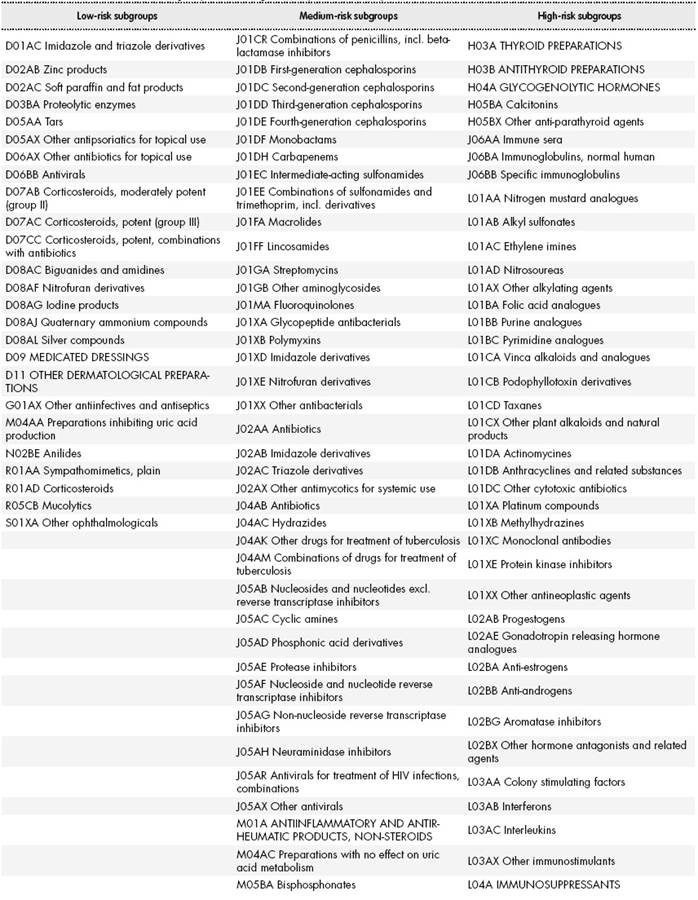

The scenarios comprised three lists: low-risk (scenario 1), medium-risk (scenario 2), and high-risk medications (scenario 3). The low-risk list contained the ATC subgroups unlikely to cause patient discomfort or clinical deterioration; medium-risk list contained the ATC subgroups with the potential to cause moderate discomfort or clinical deterioration; and high-risk list contained the ATC subgroups with the potential to cause severe discomfort or clinical deterioration.

The literature review and web search yielded 47 subgroups that were classified as low-risk, 136 subgroups as medium-risk, and 115 subgroups as high-risk.

Results of the evaluation rounds

A total of 298 ATC groups were evaluated and rated. Sixty-one (21%) of the ATC subgroups included in the HPG were classified as low-risk, 126 (42%) as medium-risk, and 111 (37%) as high-risk. The most frequent ATC subgroups in the low-risk list belonged to group A “Alimentary tract and metabolism” (44%, n = 27), the most frequent in the medium-risk list belonged to group J “Antiinfectives for systemic use” (32%, n = 40), and the most frequent in the high-risk list belonged to groups L “Antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents” (29%, n = 32) and N “Nervous system” (26%, n = 29) (see Figure 1).

Nine experts were selected to serve on the panel. All 9 completed the first round and 8 completed the second.

In the first round, 266 ATC subgroups were classified as appropriate, 32 were classified as uncertain, and none were classified as inappropriate. In the second round, the experts met face-to-face to re-evaluate the ATC subgroups classified as uncertain. After discussion, 12 subgroups remained in the same class, whereas 20 subgroups changed class by consensus (Table 2). The final rating panel classified all subgroups as appropriate.

Table 3-1, Table 3-2, Table 3-3 and Table 3-4 shows the final lists of ATC subgroups according to their potential risk.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to stratify medications used in hospital care according to their potential risk (low to high-risk). The RAM was used to classify the ATC subgroups included in the HPG into low, medium, and high potential risk. In the first evaluation round, 32 groups were classified as uncertain. Because the potential risk of a medication is driven by the clinical characteristics of the patient18, the majority of the disagreements between experts could have been due to their experience in attending and treating different types of patients. However, we believe that the final results were enriched by the different criteria applied by the experts.

Some subgroups classified as uncertain were subject to further discussion. These subgroups included some dermatological subgroups, some subgroups which belong to group C10 “Lipid-modifying agents”, and some anti-Parkinson drug subgroups. The dermatological subgroups were finally reclassified as low-risk. This classification is consistent with those reported by other studies that consider this group to have no association with patient harm19,20. The subgroups that belong to group C10 “Lipid-modifying agents” were also reclassified as low-risk. The expert panel considered that the potential risk for inpatients was low. Authors such as Saeder et al.21 have also classified fibrates as low risk. The anti-Parkinson drug subgroups were reclassified as medium-risk, although the nervous system group is associated with severe adverse events22. According to the clinical experience of the experts, severe adverse events are uncommon with anti-Parkinson drugs. This reclassification is consistent with the high-alert medication list for patients with chronic disease, which excluded anti-Parkinson drugs (see Otero et al.23).

The methodology used in this study has some limitations. Firstly, although the RAM has objective characteristics, it also has subjective ones because it measures opinions24. However, this method has advantages over other methods used to reach consensus, because it uses confidential ratings and group discussion. It has good reproducibility and is considered to be a rigorous method that can be used whenever a combination of scientific evidence and expert opinion is required9,23,25. Secondly, the results of the RAM always depend on the composition of the expert panel9. The RAM panel included physicians and nurses from different medical specialities, and pharmacists with different types of clinical expertise. Thus, several fields were covered by experts with deep knowledge of all medications assessed in this study.

The lists that were created provide an objective measure that could be used during routine data collection of MEs in order to reduce subjectivity and provide a standard by which the severity of an ME can be assessed and measured. These medication lists could be a useful tool for future patient/medication safety studies, leading to better prevention measures and the improved management of follow-up activities after the detection of an ME.

Ideally, these lists could be integrated into an electronic tool to facilitate resource allocation for patients at high risk of severe MEs. It is relevant to individualize the risk assessment for each patient undergoing drug therapy21,26. Given that resources are limited, the same intervention is currently provided to all patients in our hospital, even though they may receive medications with a higher risk of adverse events. The integration of these lists into an electronic tool would assist in patient stratification.

A RAM was used to classify ATC subgroups by their potential risk (low, medium, or high). The main contribution of this study is to make these reference lists available. These lists can be integrated into a risk-scoring tool for future patient/medication safety studies.

Contribution to scientific literature

All medications can cause adverse events if they are incorrectly used. Nonetheless, certain medications are more dangerous than others. A list of high-risk medications has been published, but lists of low- and medium-risk medications are not available. This study is the first to classify medications used in hospital settings according to their potential risk. This classification is of relevance to future patient/medication safety studies and for patient resource allocation according to treatment.