Technological advancements and constant interaction with electronic devices have acquired an essential role in the general population and, especially, in the daily lives of adolescents. Currently, 70% of Spanish adolescents have a smartphone at the age of 12 (Cánovas, García-dePablo, Oliaga, & Aboy, 2014), and 98% at the age of 14 (Ditrendia Digital Marketing Trends, 2016). In fact, Spain is the European country with the largest percentage of access to the Internet via smartphones (European Commission, 2015).

Undoubtedly, the exposure to and use of the new Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) by younger children and teenagers involves serious threats (Arnaiz, Cerezo, Giménez, & Maquilón, 2016; Garaigordobil, 2017), among which cyberbullying stands out. This type of abusive behavior among peers is characterized by the use of electronic devices, mainly smartphones and the Internet, to deliberately and reiteratively harass and intimidate a victim who cannot defend him/herself easily (Giumetti & Kowalski, 2016; Smith et al., 2008).

In the past decade, a significant increase in cyberbullying in the population of children and adolescents has been confirmed in the digitalized countries in the world (Buelga, Martínez-Ferrer, & Cava, 2017). The prevalence rate of cybervictimization varies across studies from 2% to 57% (Álvarez-García, Barreiro-Collado, Núñez, & Dobarro, 2016; Arnaiz et al., 2016; Garaigordobil, 2011), with a mean prevalence of 23% (Hamm et al., 2015). Although research is not conclusive, a large number of investigations find a greater percentage of cybervictims among girls (Zych, Ortega-Ruiz, & Marín-López, 2016) and younger teenagers in the first years of Compulsory Secondary Education (7th and 8th grades) (Buelga, Cava, & Musitu, 2010; Stewart, Drescher, Maack, Ebesutani, & Young, 2014).

Cyberbullying and Traditional School Bullying

A direct link has been found between cyberbullying and traditional school bullying (Buelga et al., 2017; Mitchell & Jones, 2015). So, more than 80% of victims and bullies in school are also cybervictims and cyberbullies on the Internet (Giumetti & Kowalski, 2016; Olweus, 2013), and the consequences of this double harassment seriously affect the psychosocial adjustment and wellbeing of adolescents (Garaigordobil, 2017; Larrañaga, Yubero, Ovejero, & Navarro, 2016; Navarro, Yubero, & Larrañaga, 2018). The characteristics of technological devices increase the harm caused to the victim (García-Fernández, Romera-Félix, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2016; Navarro, Ruiz-Oliva, Larrañaga, & Yubero, 2015 Ortega-Barón, Buelga, Cava, & Torralba, 2017). According to Bauman, Toomey, and Walker (2013), the invisibility, unpredictability, and speed of cyber-aggressions are some of the factors that elevate cybervictims' psychological distress. In this way, the fact that a victim can be abused anonymously 24 hours a day and from any part of the world, without being able to predict from whom or when cyber-aggressions are going to occur, increases victims' feeling of hopelessness and lack of control over their lives. Moreover, the fact that cyber-aggressions are viral and can be seen and reproduced by an unlimited number of spectators contributes negatively to diminishing victims' psychological wellbeing.

Cyberbullying and Psychosocial Maladjustment

Numerous studies have found a significant link between cybervictimization and depressive symptomatology (Buelga, Martínez-Ferrer, Cava, & Ortega-Barón, 2019; Tokunaga, 2010), perceived stress (Garaigordobil, 2011; Shpiegel, Klomet, & Apter, 2015), low self-esteem (Cénat et al., 2014), low life satisfaction (Bili, Buljan-Flander, & Rafajac, 2014; Povedano, Hendry, Ramos, & Varela, 2011), and fatalism (Navarro et al., 2018). Cybervictimization has a very serious impact on the psychosocial adjustment of the victims, who also show high levels of loneliness. In fact, cybervictimization has been strongly related to greater social isolation (Hoff & Mitchell, 2009; Smahel, Brown, & Blinka, 2012), and numerous previous studies have linked bullying victimization to loneliness (Ostrov & Kamper, 2015; Pereda & Sicilia, 2017).

Cyberbullying victimization has also been linked to suicide ideation (Mitchell et al., 2018; Nixon, 2014; Young, Subramanian, Miles, Hinnant, & Andsager, 2016). Suicide ideation occurs when an individual repeatedly thinks about, plans, and desires to commit suicide (Beck, Kovacs, & Weissman, 1979). Van Geel, Vedder, and Tanilon's (2014) meta-analysis reveals that the relationship between suicide ideation and cyberbullying is greater than the one found with traditional bullying. These authors found that 20% of adolescents victimized through electronic devices have thought of suicide as a way to solve their problems and escape from the suffering they are experiencing. In fact, suicide ideation has been shown to be a precedent of suicidal behavior (Sánchez-Sosa, Villarreal-González, Musitu-Ochoa, & Martínez-Ferrer, 2010), and a predictor of future suicide attempts in cyberbullying victims (Hinduja & Patchin, 2010).

Some psychosocial maladjustment variables associated with bullying and cyberbullying victimization, such as loneliness, could contribute to the suicide ideation. The lack of social integration as a factor linked to suicide was initially suggested by Durkheim (1951). More recently, the interpersonal theory of suicide by Thomas E. Joiner highlighted the lack of feelings of belongingness as one of the main risk factors associated with suicide (Calati et al., 2019; Joiner, 2005). Loneliness, defined as the subjective feeling of being alone or without the desired level of social relationships (Ernst & Cacioppo, 1999), is strongly related to suicide ideation. McKinnon, Gariépy, Sentenac, and Elgar (2016), using data from 32 countries, indicated that loneliness is the main risk factor for suicide ideation among adolescents. However, the possible mediating role of loneliness in the relationship between cyberbullying victimization and suicide ideation has not previously been explored.

Other variables linked to cyberbullying victimization, such as perceived stress, depressive symptomatology, and psychological distress, could also have a mediating role in the relationship between cyberbullying victimization and suicidal ideation. Previous studies have suggested that the effects of traditional and cyberbullying victimization on suicide ideation are mediated by depressive symptoms (Mitchell et al., 2018; Reed, Nugent, & Cooper, 2015). The possible mediating role of depressive symptomatology and perceived stress in the relationship between cyberbullying victimization and suicide ideation has not previously been explored, but these variables have been related to both cyberbullying victimization and suicidal ideation (Kim, Kimber, Boyle, & Georgiades, 2018; Reed et al., 2015; Shpiegel et al., 2015; Tokunaga, 2010).

The Present Study

The main aims of the present study were: 1) to study the relationship between school bullying and cyberbullying victimization, analyzing the direct link of these variables with suicide ideation; 2) to analyze the indirect relationships between cybervictimization and suicide ideation through perceived stress, loneliness, depressive symptomatology, and psychological distress. We believe that no previous study has analyzed the links between cybervictimization and suicide ideation while taking into account in this analysis the combined and simultaneous weight of these psychosocial adjustment variables. These analyses provide new observations to clarify the direct role that cybervictimization plays in suicide ideation, as well as indirectly through some variables indicating difficulties in psychosocial adjustment. The initial hypotheses of this study were: a) cyberbullying victimization and school bullying victimization are directly related to each other; b) cyberbullying victimization and school bullying victimization have a direct effect on suicide ideation; and c) cybervictimization has an indirect effect on suicide ideation through the variables of perceived stress, loneliness, psychological distress, and depressive symptomatology. These hypotheses can be observed in Figure 1.

Method

Participants

The reference population was adolescents studying Secondary Education in Valencia Region (Spain). The selection of the participants was carried out through stratified cluster sampling, with the sampling units being secondary schools. Four secondary schools with different sizes and located in different areas of this region were selected. Three of these secondary schools were public, and one was private. The sample size - with a sampling error of ± 3.4%, a confidence level of 95%, and p = q = .5, (N = 190,773) - was estimated at 1,061 students. A total of 1,068 adolescents participated in this study, six of whom were excluded for responding systematically in the same way to the scales. Finally, the sample was composed of 1,062 adolescents, 547 boys (51.5%) and 515 girls (48.5%), ranging in age from 12 to 18 years old (M = 14.51, SD = 1.62). Of these adolescents, 44.8% were enrolled in the first cycle of Compulsory Secondary Education (CSE) (lower secondary), 39.5% were enrolled in the second cycle of CSE (upper secondary), and 15.7% were enrolled in pre-university studies. More specifically, 19.1% (n = 203) of the participants were in 7th grade, 25.6% (n = 272) in 8th grade, 19.1% (n = 203) in 9th grade, and 20.4% (n = 217) in 10th grade. Regarding pre-university studies (Bachiller), 8.9% (n = 94) of the participants were in the first year (11th grade), and 6.9% (n = 73) were in the second year (12th grade).

Instruments

Adolescent Victimization through Mobile Phone and Internet Scale (CYBVIC; Buelga et al., 2010; Buelga, Cava, & Musitu, 2012). This scale consists of 18 items rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always). The scale measures an adolescent's experience as a victim of cyberbullying through a mobile phone and the Internet in the past 12 months. The scale consists of two subscales: mobile phone victimization (e.g., "Someone called me and hung up") and Internet victimization (e.g., "Someone went into my private accounts, and I couldn't do anything about it"). The CFA using the maximum likelihood estimation method confirmed the fit of the proposed measurement model (S-Bχ2 = 238.90, df = 124, p < .001, CFI = .927, NNFI = .910, RMSEA = .030, 90% CI [.024, .035]) and the internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = .89).

School Bullying Victimization Scale (Cava, Musitu, & Murgui, 2007). This scale uses 20 items to evaluate how often adolescents have experienced situations of bullying victimization at school in the past year. The scale is composed of three factors: relational victimization, consisting of 10 items describing situations such as being a victim of malicious rumors or being socially isolated (e.g., "A classmate told others not to have anything to do with me"); physical victimization, 4 items describing situations such as being hit or pushed (e.g., "A classmate hit or slapped me"); and verbal victimization, 6 items describing situations such as being insulted or called a nickname (e.g., "A classmate insulted me"). The response range of the items is from 1 (never) to 4 (many times). The internal consistency of these factors was .64 for physical victimization, .85 for verbal victimization, and .90 for relational victimization.

Depressive Symptomatology Scale (Herrero & Meneses, 2006). This scale is composed of 7 items (e.g., "During the past month, I felt like everything I did required an effort") that evaluate, with a response range from 1 (never) to 4 (always), the presence of depressive symptomatology in the past month. The Cronbach alpha coefficient for the reliability of this instrument in this study was .80.

Perceived Stress Scale (Herrero & Meneses, 2006). This scale consists of 4 items that evaluate, with a response range from 1 (never) to 5 (always), the perception of stressful situations in the past month (e.g., "I have felt like difficulties pile up without being able to solve them"). In this study, the Cronbach alpha coefficient for the reliability of this scale was .63.

Loneliness Scale (Expósito & Moya, 1999). This scale contains 20 items that measure, with a response range from 1 (never) to 4 (always), the feeling of loneliness experienced by an adolescent (e.g., "How often do you think there isn't anybody you can ask for help"). The Cronbach alpha coefficient for the reliability of this scale in this study was .89.

Psychological Distress Scale (Alonso, Herdman, Pinto, & Vilagut, 2010). This scale contains 10 items that evaluate, with a response range from 1 (never) to 5 (always), the presence of depression and anxiety symptoms in the past month (e.g., "How often have you felt desperate?"). In this study, the Cronbach alpha coefficient for the reliability of this scale was .84.

Suicide Ideation Scale (Mariño, Medina, Chaparro, & González-Forteza, 1993). This instrument consists of 4 items that measure suicide ideation thoughts (e.g., "I thought about killing myself"). The subject has to indicate, in a response range from 0 to 4, (0 days, 1-2 days, 3-4 days, 5-7days, respectively), the number of days on which she/he had suicidal thoughts or desires in the past week. In the current study, the Cronbach alpha coefficient for the reliability of the scale was .74.

Procedure

An informative seminar was held with the participating schools in order to explain the aim of the project to the teachers and principals. After obtaining parental authorization for their children's participation in the study, research team members administered the instruments during school hours. Filling out the scales took participants about 50 minutes. The students were informed that their participation in this research was voluntary and anonymous, that their data were confidential, and that they could drop out of the study at any time. The privacy of their answers was guaranteed in order to avoid possible social desirability effects. Thus, students responded anonymously without any identification, and their anonymous information was used only by the research team, who were present during this session and collected the scales once they had been completed by the students. The data collection in the participating schools lasted two weeks.

Data Analysis

The research design is non-experimental, correlational, and cross-sectional. The data analyses used for this study were the following: first, the correlations among all the study variables were calculated with the Pearson correlation index, as well as the means, standard deviations, and differences in means through Student's t-test of these variables according to gender; next, a structural equation modeling was tested with the EQS 6.0 program (Bentler, 1995) in order to explore the direct and indirect effects of cyberbullying on suicide ideation. The factors included in the model were six observable variables (cyberbullying victimization, perceived stress, depressive symptomatology, psychological distress, loneliness, and suicide ideation) and a latent factor composed of three observable variables (physical bullying, verbal bullying, and relational bullying). Because of the data's deviation from multinormality (Mardia normalized coefficient = 32.78), robust estimators were used to determine the goodness of fit of the model and the statistical significance of the coefficients. In addition, given that the use of only one global fit measure of the model is not recommended (Hu & Bentler, 1999), CFI, GFI, TLI, AGFI, RMSEA, and χ2/df were calculated. A model fits the observed data well when the ratio between the chi-squared statistic and the degrees of freedom is less than three, the fit indexes are equal to or above .95, and the RMSEA is below .05 (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The general assumptions about the use of structural equation modeling (linearity of the relations maintained, relevance of the variables included, absence of multicollinearity) were also taken into account in the analysis. The standardized regression coefficients included in the model were estimated, analyzing their significance level. Finally, a multigroup analysis was carried out in order to verify whether the relationships observed between the variables tested in the model remained invariant across gender.

Results

Table 1 presents the correlations matrix of the study variables, as well as the means, standard deviations, and Student's t-test results based on gender.

Table 1. Correlations among Variables, Means, Standard Deviations, and Results of the t-Test according to Gender

Note. CYB = cyberbullying victimization; PB = physical bullying victimization; VB = verbal bullying victimization; RB = relational bullying victimization; PS = perceived stress; L = loneliness; DS = depressive symptomatology; PD = psychological distress; SI = suicide ideation; B/G = boys/girls; M = mean; SD = standard deviation; t = Student's t-test. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

The correlational analysis shows that there are statistically significant correlations among all the variables considered in this study. Cyberbullying victimization was found to correlate higher with relational bullying victimization (r = .65 p < .01), verbal bullying victimization (r = .57, p < .01), and physical bullying victimization (r = .45 p < .01). There are also significant correlations between cyberbullying victimization and all the psychological maladjustment indicators. The highest correlations are observed with psychological distress (r = .42, p < .01), depressive symptomatology (r = .36, p < .01), and suicide ideation (r = .34, p < .01). Regarding the differences according to gender, data indicate that there are statistically significant differences in all the variables, with the exception of verbal bullying victimization and loneliness, where there are no differences between boys and girls. The mean of girls is significantly higher in all these variables, with the exception of physical bullying victimization where the mean of boys is higher.

Later, a structural equation modeling was calculated with the purpose of analyzing the effects of cyberbullying victimization on suicide ideation, also taking into account the direct influence of school bullying victimization on the final variable. The calculated model is composed of six observable variables (cyberbullying, perceived stress, loneliness, depressive symptomatology, psychological distress, and suicide ideation) and a latent factor (school bullying victimization) formed by the observable variables of physical bullying victimization, relational bullying victimization, and verbal bullying victimization. Their factor saturations are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Estimations of Parameters, Standard Errors, and Associated Probability

Note. Robust statistics; standard error in parentheses; 1set at 1.00 during the estimation. ***p < .001 (bilateral).

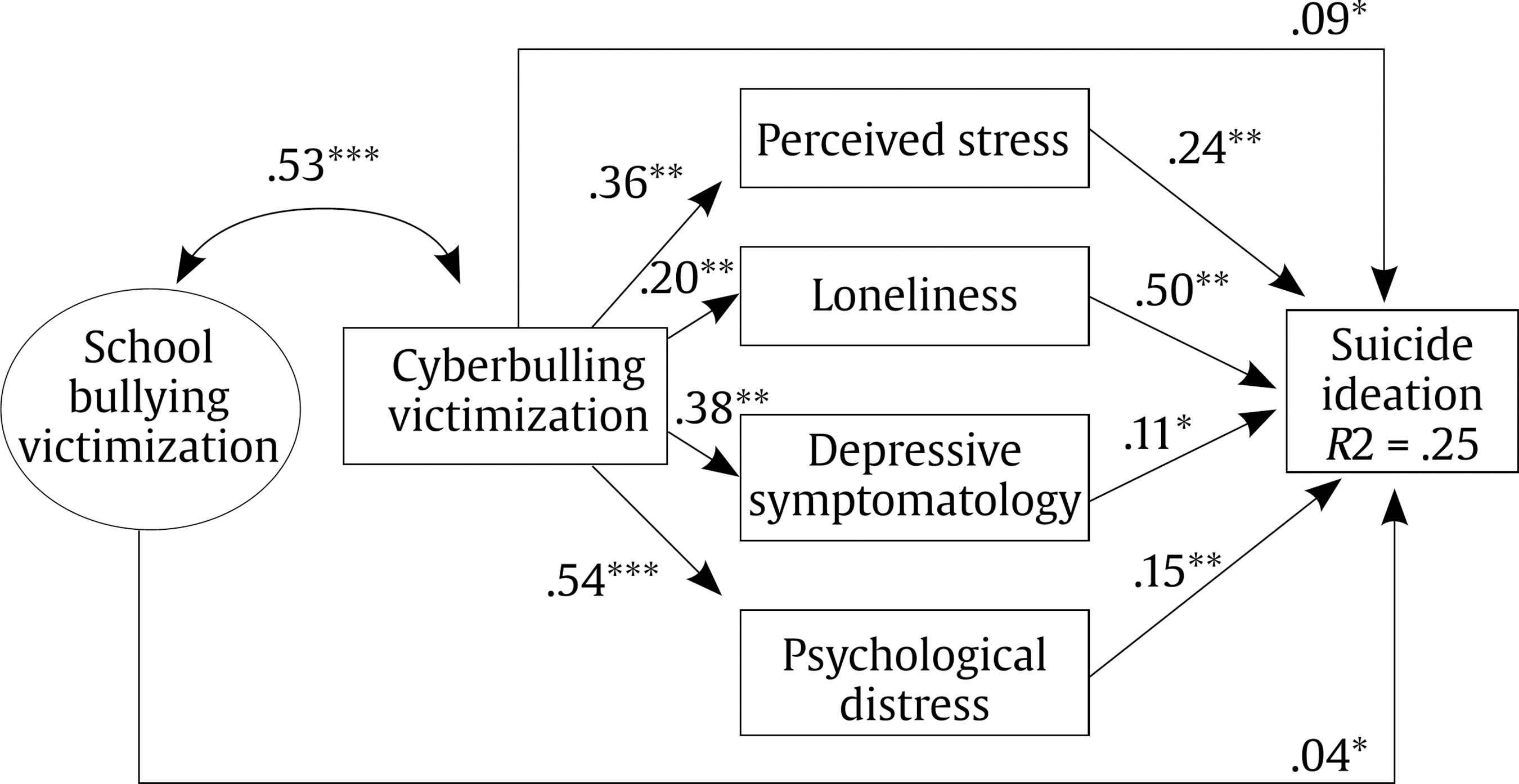

The results of the hypothesized model analysis indicated that this model showed an adequate fit to the data. The indexes obtained were CFI = .98, GFI = .99, TLI = .98, AGFI = .98, RMSEA = .04, and χ2/df = 2.7. This model explains 25% of the final variable, suicide ideation. Figure 2 shows the graphic representation of the final structural model with the standardized coefficients and their associated statistical significance levels.

Figure 2. Final Model of the Direct and Indirect Effects of Cyberbullying Victimization on Suicide Ideation.*p < .05, **p <.01, ***p < .001.

First, the obtained results confirm that school bullying victimization and cyberbullying victimization correlate positively with each other (r = .53, p < .001), and also that there are direct effects of school bullying victimization (β = .04, p < .05) and cyberbullying victimization (β = .09, p < .05) on suicide ideation. Also, the results of the model suggest significant indirect relationships between cyberbullying victimization and suicide ideation through the variables of perceived stress, loneliness, depressive symptomatology, and psychological distress. The results of the coefficients (see Figure 2) indicate a significant positive direct relationship between cyberbullying victimization and perceived stress (b = .36, p < .01), loneliness (b = .20, p < .01), depressive symptomatology (b = .38, p < .01), and psychological distress (b = .54, p < .001). Moreover, perceived stress (b = .24, p < .01), loneliness (b = .05, p < .05), depressive symptomatology (b = .11, p < .05), and psychological distress (b = .15, p < .01) are positively related to suicide ideation.

Finally, a multigroup analysis was carried out to test the structural invariance of the calculated model based on gender (boys and girls). For this purpose, two models were compared: the first, with constrictions, assumes that all the relationships between the variables are equal for boys and girls, whereas the second model, without constrictions, estimates all the coefficients in both groups. If the statistical comparison of the two models reveals no differences between them, the model with more degrees of freedom is the most appropriate. As Table 3 shows, no significant differences were found between the model with no restrictions and the restricted model, S-Bc2 (11, 1062) = 18.27, p = .075. Thus, the model with restrictions was found to be statistically equivalent for both groups.

Table 3. S-Bχ2, Degrees of Freedom, Associated Probability, and Model Comparisons

Note. The model comparisons based on the Satorra-Bentler χ2 were carried out following the procedure described in Crawford and Henry (2003).

Discussion

The main goal of the present study was to analyze the relationships between cyberbullying victimization and suicide ideation in adolescents. The results suggest that cybervictimization has a direct effect on suicide ideation. Likewise, they show that cybervictimization has an indirect effect on suicide ideation through perceived stress, loneliness, depressive symptomatology, and psychological distress. Moreover, the first hypothesis of our study was confirmed, which proposed that cyberbullying and school bullying victimization were directly related to each other. This result coincides with numerous scientific studies that show the existence of a continuity between school bullying and cyberbullying victimization (Giumetti & Kowalski, 2016; Kowalsky & Limber, 2013; Yubero, Navarro, Elche, Larrañaga, & Ovejero, 2017). As Hemphill et al. (2012) indicate, school bullying victimization is a risk factor that increases a victim's probability of being a target of bullying in another context, in this case, the virtual environment.

Both modalities of violence toward a victim have, as confirmed in our study, some negative consequences for his/her psychosocial adjustment. Thus, there is confirmation of the existence of a direct effect of school bullying victimization, on the one hand, and cyberbullying victimization, on the other, on suicide ideation. Our results also reveal, consistent with Van Geel et al. (2014), that the relationship between cyberbullying victimization and suicide ideation is higher than the one found with school bullying. The negative impact of cybervictimization seems, therefore, to cause a greater state of desperation in victims than the one produced by traditional bullying, and this desperation is directly related to the ideation of recurrent suicidal thoughts. As Navarro et al. (2018) indicate, one's meaning in life can be seriously harmed by repeated experiences of cyberbullying, leading to feelings of impotence and the inability to resolve the problem in victims, as well as helplessness due to the feeling that no one can help them to escape the situation of cybernetic abuse.

With regard to the main aims of this study related to the effects of cybervictimization on suicide ideation, the results indicate that the relationship between cyberbullying and self-destructive thoughts is higher when emotional distress is specifically considered in this association. Thus, the results of the present study confirm our third hypothesis, which proposes that cyberbullying victimization has an indirect effect, through perceived stress, loneliness, psychological distress, and depressive symptomatology, that increases suicide ideation. Our results indicate that cyberbullying victimization is strongly related to some variables of psychosocial maladjustment, such as the psychological distress that evaluates the presence of depression and anxiety symptomatology, being an indicator of emotional distress. Psychological distress shows the highest relationship with cyberbullying victimization. In addition, a high association between cibervictimization and depressive symptomatology can be observed. Previous research also finds high rates of depressive symptomatology and desperation in victims of cyberbullying (Aboujaoude, Savage, Starcevic, & Salame, 2015). In this regard, Raskauskas and Stolz (2007) show that almost all (93%) of the adolescents bullied through ICTs present depressive symptoms. Regarding the relationship found between cyberbullying victimization and perceived stress, this may be due to cybervictims' high level of constant alertness due to the inability to escape the cybernetic bullying and control their lives (Kowalski, Giumetti, Schroeder, & Lattanner, 2014; Ortega-Barón, Buelga, Ayllón, Martínez-Ferrer, & Cava, 2019). In fact, in a very interesting study, González-Cabrera, Calvete, León-Mejía, Pérez-Sancho, and Peinado (2017) found that victims of cyberbullying present high levels of secretion of the stress hormone (cortisol), which seems to confirm the constant level of activation that occurs as a consequence of cyberbullying.

In addition to these psychological distress indicators, our results also point to the existence of significant relationships between cyberbullying victimization and perceived loneliness. This finding is consistent with previous studies that also find a close connection between cyber victimization and feelings of loneliness in victims (Heiman, Olenik-Shemesh, & Eden, 2015; Larrañaga et al., 2016). Unpopularity and rejection by peers in an especially important stage like adolescence (Buelga & Pons, 2012; Crespo-Ramos, Romero-Abrio, Martínez-Ferrer, & Musitu, 2017) produces strong feelings of loneliness and social isolation in cybervictims (Arnaiz et al., 2016; Martínez-Ferrer, Romero-Abrio, Moreno-Ruiz, & Musitu, 2018), which leads them to experience an existential emptiness about the meaning of their lives (Stillman et al., 2009).

Moreover, our results reveal that all of the psychological maladjustment indicators have a significant effect on suicide ideation. These data are consistent with previous studies that identify these psychological variables as risk factors or antecedents of suicide ideation (Hinduja & Patchin, 2010; Sánchez-Sosa et al., 2010). Hopelessness and the presence of mood state disorders are identified as some of the variables that most influence the transition from suicide ideation to the first suicide attempt or to consummated suicide (Ganz, Braquehais, & Sher, 2010; Sánchez, Muela, & García, 2014). The results of this study also support the interpersonal theory of suicide (Calati et al., 2019; Joiner, 2005) because loneliness is the variable with the highest direct effect on the suicide ideation of adolescents who experience cybervictimization. Our data confirm that cyberbullying victimization produces a strong emotional impact and feelings of loneliness in victims, with a significant effect on their suicide ideation.

Finally, this study contributes novel results about the relationships between cyberbullying and suicide ideation in the adolescent population, making it possible to advance the knowledge about the impact of this serious technological abuse problem on victims. The role of loneliness as a mediating variable in the relationship between cyberbullying victimization and suicide ideation, observed in the present study, can be especially useful for developing prevention strategies. In this regard, interventions with cybervictims should focus on reducing their emotional distress and feelings of loneliness in order to diminish the negative consequences of the victimization. Furthermore, some recent intervention programs designed to reduce bullying and cyberbullying (Ortega-Barón et al., 2019) have developed specific activities to encourage bystanders to support a victim when harassment occurs. This increase in social support for victims can be a useful way to prevent the negative consequences of cyberbullying, including suicide ideation.

However, this study presents some limitations that have to be mentioned. The cross-sectional and correlational design of this study does not allow us to establish causal relationships between the variables analyzed. A longitudinal study would make it possible to clarify the relationships established between the different study variables. It would also be interesting to include other variables in future studies, such as impulse control, which has been shown to be highly related to suicide ideation. Impulse control, depression, and hopelessness are, in fact, high risk factors in the transition from suicide ideation to planning an attempt and committing suicide (Sánchez et al., 2014). It would also be of interest to analyze not only psychological variables, but also the role played by family as a protector factor of children's wellbeing (Garaigordobil & Machimbarrena, 2017; Martínez-Ferrer et al., 2018; Muñiz, 2017; Ortega-Barón, Postigo, Iranzo, Buelga, & Carrascosa, 2019; Pereda & Sicilia, 2017).

In sum, in spite of its limitations, this study provides suggestive ideas for future studies, where qualitative techniques could also be used to understand the effect of cyberbullying on wellbeing and mental health from victims' perspective. Finally, the present study can be useful in designing and promoting policies for the prevention and eradication of the growing worldwide problem of cyberbullying in the population of children and adolescents.