Introduction

In the last years, there has been an increasing interest in healthcare professionals' inner life, which has given rise to the definition of several terms aiming at facilitating an omni-comprehension of the healing relationship established between clinician and person who suffers. One of these traditional concepts is burnout, which has been defined as a syndrome characterized by emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and lack of accomplishment (Maslach & Jackson, 1981). Healthcare professionals represent a highly vulnerable group that suffers from burnout syndrome, as evidenced by its high prevalence (Parola, Coelho, Cardoso, Sandgren, & Apóstolo, 2017). But burnout syndrome is not the only consequence derived from the helping relationship established between clinician and suffering person. When studying professionals' emotional problems derived from working with patients, other processes have been recently defined, such as compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction (Stamm, 2002).

Under the term professional quality of life, Stamm (2010) groups burnout syndrome, compassion fatigue, and compassion satisfaction. Compassion fatigue is defined as the negative effect caused when assisting traumatized people (Bride, Radey, & Figley, 2007), debilitating fatigue derived from the empathic responses to others' suffering (LaRowe, 2005), which diminishes professionals' ability for compassionate care (Coetzee & Klopper, 2010). Compassion satisfaction, in its turn, has been defined as the opposite of compassion fatigue and has been defined as the joy resulting from helping others (Kearney, Weininger, Vachon, Harrison, & Mount, 2009). An in-depth understanding of the variables that influence professional quality of life, as well as the study of the effectiveness of intervention programs, are well-justified needs, since improvements in these areas have shown an increase in patients' satisfaction and in the quality of the care provided (Krasner et al., 2009; Salyers et al., 2017). For example, Dasan, Gohil, Cornelius, and Taylor (2015) found a relation between compassion fatigue, work stress, irritability with patients and colleagues, and a reduction in the standards of care.

From bibliography we know the impact of variables such as awareness or mindfulness and the capacity for compassion on professionals' quality of life. Specifically, a negative relationship has been observed between mindfulness and burnout syndrome and compassion fatigue, and a positive relationship with compassion satisfaction (Sansó et al., 2015). Mindfulness is a state of mind characterized by focusing attention on the present moment with acceptance and without judgment (Morrison, Goolsarran, Rogers, & Jha, 2014). This ability can be trained and improved through meditation (Coffey, Hartman, & Fredrickson, 2010). Several studies offer evidence about how contemplative and meditation training improves psychological well-being (Ruiz-Robledillo & Moya-Albiol, 2015; Sansó et al., 2018; Soler et al., 2014) and helps develop attitudes of calm, clarity, concentration, and resilience (Oñate & Calvete, 2017; Walsh & Shapiro, 2006). Dos Santos et al. (2016), for example, found a positive relationship between a mindfulness meditation based stress reduction program in Brazilian nursing professionals and an improvement in nursing activities. A recent review of the topic has showed the development of mindfulness through MBIs in the workplace, which in turn led to favorable results for anxiety, stress, and distress/anger (Lomas et al., 2017). Results for burnout were, however, more equivocal, with some of the MBIs failing to observe a significant improvement in this variable. This same research group found contradictory results regarding the improvement of mindfulness in review studies centered on healthcare professionals, with important variations in the results in each of the dimensions (Lomas, Medina, Ivtzan, Rupprecht, & Eiroa-Orosa, 2018). Results on burnout were, again, even less clear, with half of the reviewed interventions reporting significant improvements and the other half reporting no significant change.

As regards compassion, it has been defined as the feeling that arises from witnessing suffering and involves a great desire to help (Goetz, Keltner, & Simon-Thomas, 2010), that is to say, it implies awareness of oneself and other beings'suffering, along with the desire to avoid it (Gilbert, 2015).

Within programs addressed to improve either mindfulness or compassion, we can find generic programs, focused on stress reduction (traditionally known as Mindful-Based Stress Reduction Training, MBSTR), and specific programs, oriented to compassion, such as the Compassion Cultivation Training (CCT) (Amutio-Kareaga, García-Campayo, Delgado, Hermosilla, & Martínez-Taboada, 2017; Orellana-Rios et al., 2018). There is scientific evidence showing that mindfulness-based programs and compassion cultivation training can reduce the stress perceived by professionals and improve the level of mindfulness and emotional regulation (Aranda et al. al., 2018; Burton, Burgess, Dean, Koutsopoulou, & Hugh-Jones, 2017; Jazaieri et al., 2014). For example, CCT proved significant improvements in scores of self-compassion, mindfulness, and interpersonal conflict in healthcare professionals' (Scarlet, Altmeyer, Knier, & Harpin, 2017).

Although the wide bulk of literature studying the efficacy of these programs on healthcare professionals and other many populations, we have found few studies comparing different training programs. Only a recent publication carried out by Brito, Campos, and Cebolla (2018) compares the effect of two training programs: MBSTR and CCT. In this study, both programs obtained good results on participants' well-being. However, results were better for CCT when it came to increasing compassion skills. To date, we are not aware that a similar study has been carried out specifically in healthcare professionals.

Taking previous research into account, the aim of this study is twofold. Firstly, to assess the effectiveness of two interventions based on contemplative practices, MBSRT and CCT, to increase the levels of mindfulness, empathy, and self-compassion in healthcare professionals and, through these improvements, to enhance professional quality of life and its dimensions: burnout syndrome, compassion fatigue, and compassion satisfaction. Our second aim is to compare this effectiveness, in order to provide evidence on what specific type of intervention is more useful in this context.

The working hypotheses, then, are as follows:

H1: Both interventions, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Training (MBSRT) and Compassion Cultivation Training (CCT), will improve healthcare professionals' levels of mindfulness, empathy, and, self-compassion.

H2: As healthcare professionals' levels of mindfulness, empathy, and self-compassion seem to be related to their professional quality of life, both interventions, MBSRT and CCT, will also improve participants' professional quality of life.

H3: The CCT group will have a higher increase in their levels of the variables related to compassion cultivation, that is empathy, self-compassion, and dimensions of professional quality of life related to compassion, which are compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue.

Method

Design and Procedure

Primary care healthcare professionals from the Official Association of Physicians in the Balearic Islands were invited to participate in two training programs, MBSRT and CCT, both of 60-hour duration. The programs were developed during October 2016 and May 2017, each of them in a three-month period, in which participants realized three intensive weekend workshops and also practical weekly sessions. Data of the first time point was gathered in the first session of each of the programs, and data of the second time point or post-intervention was gathered in the last session of the programs.

Inclusion criteria included being an active worker in the Balearic Islands healthcare system. In order to improve participants' engagement with the training, the allocation was non-randomized; instead, professionals could choose the training they preferred by inscription order. All the participants received the intervention of their preference.

Participants

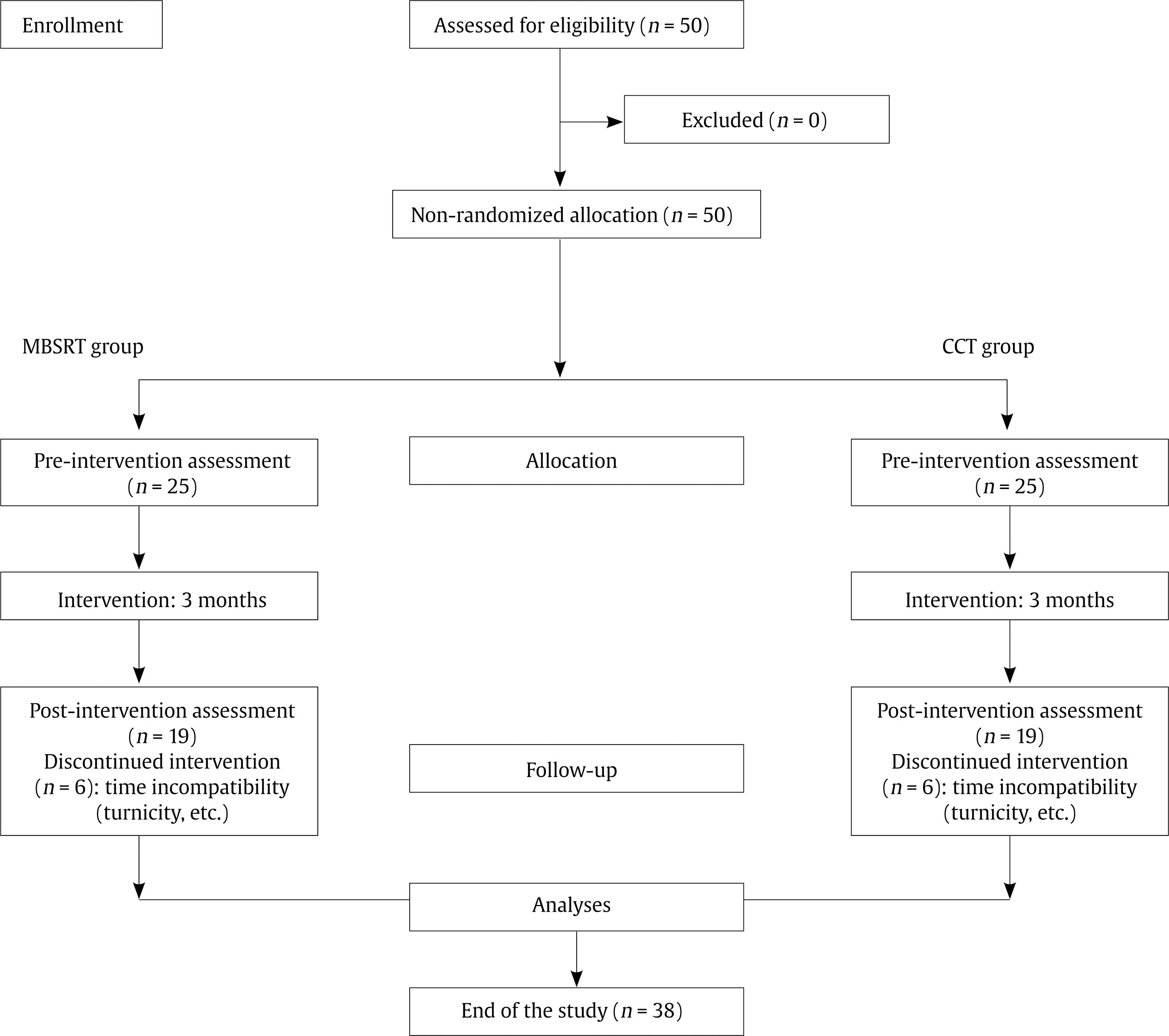

Nineteen out of the 25 participants of each group of intervention completed successfully the training and answered pre- and post-survey intervention (see Figure 1). In Table 1 there is a description of participants'characteristics for each intervention group.

Measurement Instruments

Together with the sociodemographic data, we included instruments measuring mindfulness, empathy, self-compassion, and professional quality of life.

Five-Facets Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Baer, Smith, Hopkins, Krietemeyer, & Toney, 2006) to assess mindfulness. This instrument is composed of 39 items, scoring on a five-point Likert-type scale, from 1, never or very rarely true, to 5, very often or always true. The aim of the FFMQ is to assess mindfulness in a comprehensive way, with five dimensions: observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judgement of inner experience, and non-reactivity to inner experience. Estimations of reliability using Cronbach's alpha were .79 for observing, .91 for describing, .81 for acting with awareness, .93 for non-judgement, and .85 for non-reacting.

The Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI; Davis, 1980, 1983) was used to assess empathy. This instrument includes 28 self-report items which score on a Likert-type scale of five points, from 1, does not describe me well, to 5, describes me very well. The items are grouped into four subscales assessing four dimensions of empathy: perspective taking, fantasy, empathic concern, and personal distress. Cronbach's alpha in this study was .66 for perspective taking, .70 for fantasy, .65 for empathic concern, and .83 for personal distress.

The Self-Compassion Scale (SCS; Neff, 2003) was used to establish self-compassion levels. The SCS is formed by 12 items scoring from 1, 'almost never', to 5, 'almost always', in a Likert-type scale. It assesses three main components: self-kindness (and its opposite, self-judgment/self-criticism), common humanity (and its opposite, isolation) and mindfulness (and its opposite, over-identification). Self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness conform the positive self-compassion, with an estimation of Cronbach's alpha of .86 in this study; whereas their opposites, self-judgment, isolation, and overidentification conform negative self-compassion, with a Cronbach's alpha of .84 in the study.

Short version of the Professional Quality of Life Scale (Short ProQol; Galiana et al., 2019). This short version of the ProQol (Stamm, 2010) evaluates the same three dimensions of the original scale: compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout syndrome, but with only three items per factor. It has shown adequate psychometric properties in samples of Spanish, Argentinian, and Brazilian healthcare professionals (Galiana et al., 2019). Internal consistency estimates for this study were .84 for compassion satisfaction, .78 for compassion fatigue, and .79 for burnout syndrome.

Data Analyses

To study the effectiveness of each intervention, four mixed multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) were carried out. In each of them, the within-subjects independent variable was time, with two categories (pre- and post-intervention), and the between-subjects independent variables was group, also with two categories (MBSRT vs CCT training). The first MANOVA included the dimensions of mindfulness as dependent variables – observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judgement of inner experience, and non-reactivity to inner experience . In the second MANOVA, the dependent variables were the dimensions of self-compassion – self-kindness, mindfulness, common humanity, over-identification, isolation, and self-judgment. The third MANOVA included the dimensions of empathy as dependent variables – perspective taking, fantasy, empathetic concern, and personal distress. And the last MANOVA included the dimensions of professional quality of life as dependent variables – compassion satisfaction, compassion fatigue, and burnout syndrome.

MANOVA evaluates differences in the means of dependent variables for the different categories of independent variables, and also for the effect of interaction. The effect of time will indicate if interventions are, in general, effective; group effect will indicate if there are differences between groups in the general mean, without taking into account the temporal point; it will be the effect of interaction time * group the one that indicates if there are differences due to the type of training. Taking the proposed hypotheses into account, the effect of time will respond to hypotheses 1 and 2, and the effect of the interaction to hypothesis 3.

Within the different multivariate criteria to study the effects of independent variables, we chose Pillai's criteria, since they are the most robust ones for violations of statistical assumptions (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2007). The effect size was estimated with partial eta-squared (η2). Cohen's effect size cut-offs criteria were used for descriptive ends: 02, .13, and .26, for small, medium, and big effects, respectively (Cohen, 1992).

Results

First of all, groups were compared in their sociodemographic characteristics and main outcome variables at baseline level. Groups showed no differences regarding gender distribution, η2(1) = 1.393, p = .238. They showed, however, differences in age, t(35) = 2.285, p = .028. However, as far as we know, there is no evidence of differential effects of neither Mindful-Based Stress Reduction Training (MBSRT) nor Compassion Cultivation Training (CCT) depending on the age group. Regarding the comparison on the main outcome variables, no statistically significant differences were found, except for levels of burnout, which were higher for MBSRT group (see Table 2). The influence of differences in the pre-intervention time point were, however, controlled for in the analyses testing the intervention effect.

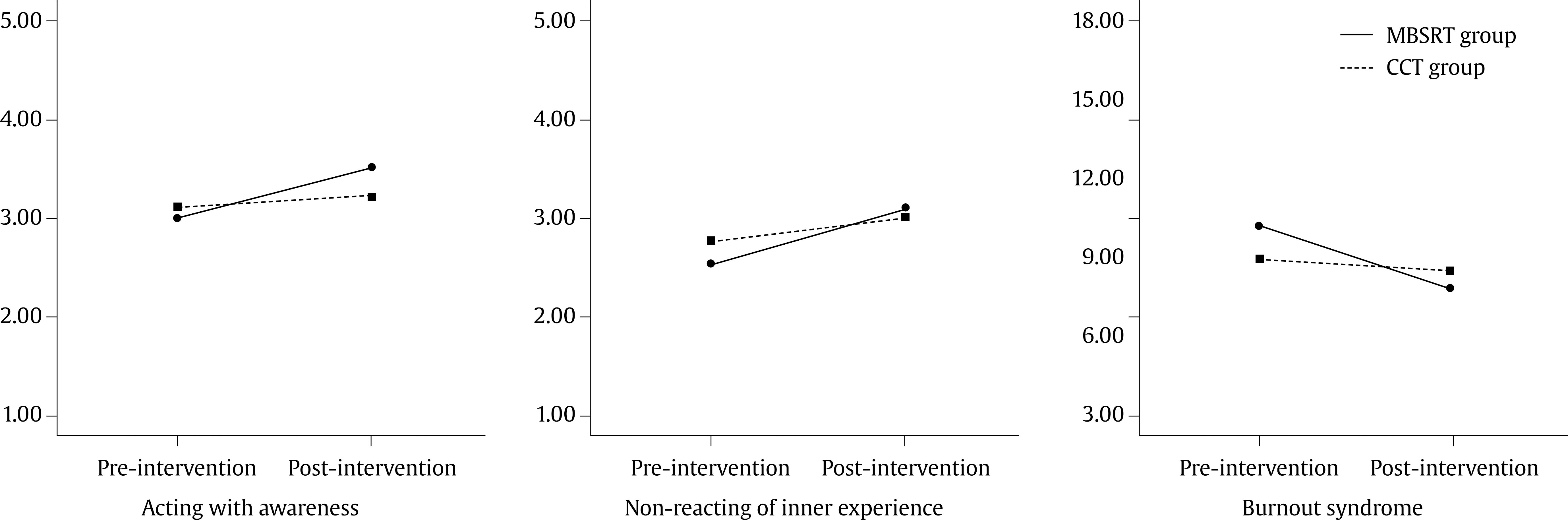

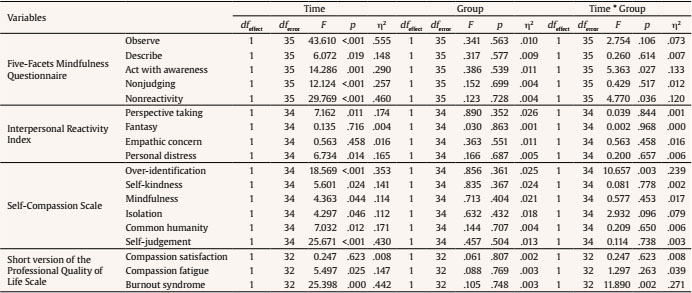

The first MANOVA studied the effect of time and group variables and their interaction in FFMQ dimensions. Results showed a statistically significant and big effect size of time, Pillai's trace = .714, F(5, 31) = 15.494, p < .001, η2 =.714, a statistically non-significant and small effect size of group, Pillai's trace = .071, F(5, 31) = 0.403, p = .793, η2 = .071, and a statistically significant and big effect size of the interaction time * group, Pillai's trace = .306, F(5, 31) = 2.734, p = .037, η2 = .306. The statistically significant effect of time showed the effectiveness of treatments for improving mindfulness. The statistically significant effect of the interaction, in turn, showed that such effectiveness varied across groups or, in this case, type of training. As shown in Table 3, follow-up ANOVAs showed a differential effect of training in two dimensions of mindfulness: acting with awareness and non-reacting to inner experience. In both cases, as can be seen in Figure 2, the effect favored the MBSRT group, whose participants started the training (pre-intervention time point) with lower levels in the two dimensions of mindfulness and ended with higher levels, compared to CCT group. That is to say, MBSR training had a higher effect on mindfulness. Means'details can be consulted in Table 4.

Figure 2. Marginal Means Estimated for the MBSRT Group and the CCT Group in the Pre-Intervention and Post-Intervention Time Points, for the Dimensions with Statistically Significant Interaction Effect.

Table 3. Follow-up ANOVAs for the Effects of Time, Group, and the Interaction on the Dependent Variables

Table 4. Variable Means and Standard Deviations for the Two Time Points (before and after the Interventions) for the MBSRT Group and the CCT Group

MANOVA studying the effect of the independent variables on the dimensions of empathy showed a statistically significant and big effect of time, Pillai's trace = .330, F(4, 31) = 3.819, p = .012, η2 = .330, but not for group, Pillai's trace = .276, F(4, 31) = 1.845, p = .125, η2 = .276, neither for the interaction time * group (Pillai's trace = .259, F(4, 31) = 1.687, p = .160, η2 = .259. Therefore, the interventions improved healthcare professionals'levels of empathy, and in the same amount (with no differential effectiveness depending on the type of training).

The third MANOVA studied the effect of the independent variables on self-compassion dimensions and showed a statistically significant and big effect of time, Pillai's trace = .636, F(6, 29) = 8.454, p < .001, η2 =. 636, but no statistically significant effects for group, Pillai's trace = .033, F(6, 29) = 0.261, p = .901, η2 = .033. Again, training did successfully increase levels of self-compassion, and in the same amount.

Finally, the last MANOVA studied the effect of the two trainings on the professional quality of life. Results showed statistically significant and big effects of time, Pillai's trace = .498, F(3, 30) = 9.925, p < .001, η2 = .498, and the interaction of time * group (Pillais' trace = .304, F(3, 30) = 4.359, p = .012, η2 = .304, but the effect of group was statistically non-significant and small, Pillai's trace = .031, F(3, 30) = 0.324, p = .808, η2 = .031. As it happened with the MANOVA studying the effect of independent variables on mindfulness dimensions, the statistically significant effect of time showed the effectiveness of treatments for improving professional quality of life, and the statistically significant effect of the interaction, in turn, showed that such effectiveness varied depending on the type of training. Follow-up ANOVAs for time * group interaction effect showed a differential effect of training for only one dimension of professional quality of life: burnout syndrome (see Table 3). This effect favored MBSRT group, in the line of results found when mindfulness was studied. Participants of MBSR training's levels of burnout syndrome showed a higher decrease when compared to the decrease of the levels of the participants in the CC training (see Figure 2). The details of burnout syndrome means for both groups can be seen in Table 4.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to test three hypotheses related to the effect of two different contemplative-based trainings, Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction Training (MBSRT) and Compassion Cultivation Training (CCT).

First of all, we hypothesized a positive effect of both interventions on healthcare professionals' levels of mindfulness, empathy, and self-compassion. For this purpose, we studied the effect of time in the means of both MBSRT and CCT groups, with our results showing statistically significant effects in the three variables under study. In each of the variables, the time effect size was big, especially in the case of self-compassion and mindfulness. In a recent review, Lamothea, Rondeaua, Malboeuf-Hurtubiseb, Duvala, & Sultana (2016) found that five out of seven studies offered evidence that MBSR improved healthcare professionals' empathy (Barbosa et al., 2013; Bazarko, Cate, Azocar, & Kreitzer, 2013; Krasner et al., 2009; Martin-Asuero et al., 2014; Shapiro, Astin, Bishop, & Cordova, 2005). Regarding mindfulness level, several studies have shown that MBSR improved mindfulness level (Brooker et al., 2013; Martin-Asuero et al., 2014; Sansó et al., 2018; Shapiro, Brown, & Biegel, 2007; Suyi, Meredith, & Khan, 2017), like the present study. Also, the increase found in self-compassion levels for MBSR training participants was expected, as it is in line with previous studies (Bazarko et al., 2013; Erogul, Singer, McIntyre, & Stefanov, 2014; Kuyken et al., 2010; Sansó et al., 2018). This was also the case for CCT, that effectively enhanced mindfulness (Brito et al., 2018; Delaney, 2018; Jazaieri et al., 2014; Neff & Germer, 2013), self-compassion (Brito et al., 2018; Delaney, 2018), and empathy (Brito et al., 2018) across literature.

Our second hypothesis claimed for an effect of both interventions on the levels of participants' professional quality of life, with results showing a big and statistically significant effect of the programs on this variable. In fact, the independent variable time explained almost half of the variance of professionals' quality of life. We found several studies proving the effect of both kinds of programs (CCT and MBSRT) on any of the three dimensions of professionals' quality of life (burnout syndrome, compassion satisfaction, and compassion fatigue) (Delaney, 2018; Olson, Kemper, & Mahan, 2015; Potter et al., 2013; Rabb, 2014; Sansó et al., 2015, 2018). In most of them, the main measure to assess their effectiveness on quality of life was the Professional Quality of life (ProQol) (Stamm, 2010). For instance, Delaney (2018) examined the effect of an eight-week mindful self-compassion training intervention on nurses' compassion fatigue and resilience and participants' lived experience of the effect of training. Potter et al. (2013), in turn, evaluated a resilience program designed to train oncology nurses in compassion fatigue in Midwestern United States. Nurses attended a five-week program involving five 90-minute sessions on compassion fatigue resiliency, with results showing an improvement of their professional quality of life. Also Sansó et al. (2018), this time in a sample of palliative care professionals, offered evidence of the improvement of professional quality of life after a brief mindfulness training program on mindful attention. Our second hypothesis was, then, confirmed, and confirms the role of this type of interventions when the goal is to improve healthcare professionals' quality of life.

Finally, our third and last hypothesis predicted a higher increase in the levels of the variables related to compassion cultivation in the CCT group when compared to the MBSRT group. Specifically, a statistically significant effect of the time * group interaction, favoring CCT group, was expected in the variables of empathy, self-compassion, and two of the dimensions of professional quality of life: compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue. This hypothesis was based on how compassion is addressed in the two trainings tested. MBSRT intends to implicitly teach compassion, whereas in CCT the cultivation of compassion is the aim itself. Following Brito et al.'s (2018) results, in which participants of CCT showed statistically significant higher improvements in compassion skills (including empathy and self-compassion) when compared to MBSRT participants, we hypothesized that CCT will have greater effect on variables related to compassion (empathy, self-compassion, compassion fatigue, and compassion satisfaction). However, this hypothesis was not supported by the data, as results showed a statistically significant effect of time * group interaction, but favoring MBSRT group and in the variables of mindfulness and burnout syndrome. These results can be interpreted in many different ways. On one hand, it seems that compassion can be taught implicitly, as both MBSRT and CCT can enhance participants' levels of empathy, self-compassion, compassion fatigue, and compassion satisfaction, and they do it in the same way. On the other hand, our evidence shows that what seems necessary to be taught explicitly, at least in healthcare professionals, is the power of mindfulness and the resources to cope with the burnout syndrome. Whereas compassion is easily achieved, no matter the program people attend, higher levels of mindfulness and a higher decrease in burnout levels in healthcare professionals are found when MBSRT is implemented.

The generalization of these results has to be cautious, because of the specificity of the sample and the non-randomized allocation of the participants. Healthcare professionals are considered conduits of compassion themselves (Sinclair et al., 2018), being compassion intrinsic to the delivery of care. Because of that, compassionate skills, such as empathy or self-compassion, may be abilities which healthcare professionals already dispose of, or at least they have been working with for a long time. In the case of compassion satisfaction and compassion fatigue, the effect of both interventions was the same and small, what could be explained by a ceiling effect: participants of both groups showed even in the pre-intervention assessment high levels of compassion satisfaction and low levels of compassion fatigue.

As regards the lack of a randomized allocation of participants, this is of course a limitation of the study. However, it helped to increase professionals' engagement in the courses, as they freely chose the one they preferred to attend, and resulted in a quite low experimental death, with more than 75% of participants completing the programs, whereas in similar studies this percentage ranged from 30% to 40% (Burton et al., 2017). In fact, in similar studies in which random allocation was done, participants changed groups at convenience (Brito et al., 2018; Burton et al., 2017).

It seems that both MBSRT and CCT are tools to improve healthcare levels of mindfulness, empathy, self-compassion, and professional quality of life, with MBSRT interventions having greater effects on mindfulness and the burnout syndrome. Taking into account that the burnout syndrome rate is around 50% in healthcare professionals (Burton et al., 2017; Grawitch, Ballard, & Erb, 2015; West, Dyrbye, Erwin, & Shanafelt, 2016), these programs should be a must in the healthcare system. Once their efficacy has been proved, these types of psychosocial interventions are, in the authors' view, perfectly extendable to key vulnerable groups, as informal caregivers (González-Fraile et al., 2018).