Introduction

The relationship between work and family has been conceptualised differently from various theoretical perspectives. Moreover, the significant number of reviews and meta-analyses on the topic (Allen, Herst, Bruck, & Sutton, 2000; Amstad, Meier, Fasel, Elfering, & Semmer, 2011; Byron, 2005; Ford, Heinen, & Langkamer, 2007; Hill, 2005; Zhang & Liu, 2011) is a testament to researchers’ interest in this area over time.

Traditionally, researchers have conceptualised the relationship between work and family as a type of inter-role conflict (Kahn, Wolfe, Quinn, Snoek, & Rosenthal, 1964) “in which the role pressures from the work and family domains are mutually incompatible in some respect, that is, participation in the work (family) role is made more difficult by virtue of participation in the family (work) role” (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985, p. 77). The conflict between work and family has been studied from the perspective of the ‘role stress theory’, which argues that managing multiple roles (e.g., spouse, parent, employee) is difficult and inevitably creates strain and conflict between the demands of work and family (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985).

The concept of work-family conflict has changed over time, with the work-family relationship being described as a one-dimensional or bidirectional construct often using a reductionist approach. Since researchers have acknowledged the direction of interference, work-family conflict has increasingly been recognised as consisting of two distinct, though related, concepts: work interference with family (WIF), which arises when work interferes with family life, and family interference with work (FIW), which occurs when family life interferes with work (Frone, 2003). Theory and research on WIF and FIW suggest that these two concepts may have different causes and effects (Frone, Russell, & Cooper, 1992a,1992b; Kelloway, Gottlieb, & Barham, 1999), and that individuals are more likely to experience work interference in their family lives than family interference at work (Bellavia & Frone, 2005; Frone, 2003).

Since the construct of work-family conflict was introduced, a large body of literature has examined its causes and consequences. Researchers (e.g., Byron, 2005; Eby, Casper, Lockwood, Bordeaux, & Brinley, 2005; Zhang & Liu, 2011) have divided its antecedents into three distinct categories: work-related or work domain variables (e.g., conflict, pressure and stress at work, job satisfaction, commitment, involvement, work engagement, organisational support); family-related or non-work domain variables (e.g., marital conflict, family support, number of hours spent on housework or childcare, having children at home, and age of youngest child); and demographic and individual variables (e.g., gender, personality, coping style, income). Several meta-analyses examining the work-family conflict also have identified various outcomes (Allen et al., 2000; Amstad et al., 2011; Ford et al., 2007). These potential consequences of work–family conflict can be divided into three distinct categories: work-related, family-related, and domain-unspecific outcomes (Amstad et al., 2011; Bellavia & Frone, 2005). Both directions of work–family conflict have been found to be associated with work-related outcomes, such as job satisfaction (see the meta-analyses of Bruck, Allen, & Spector, 2002), organisational commitment (e.g., Aryee, Srinivas, & Tan, 2005), engagement (e.g., Rothbard, 2001), job burnout (e.g., Peeters, Montgomery, Bakker, & Schaufeli, 2005), absenteeism (e.g., Kirchmeyer & Cohen, 1999), work-related strain (e.g., Netemeyer, Maxham, & Pullig, 2005), turnover and intent to quit (e.g., Rode, Rehg, Near, & Underhill, 2007), counterproductive work behaviour (e.g., Germeys & De Gieter, 2017), and organisational citizen behaviour (e.g., Netemeyer et al., 2005), as well as with family-related outcomes, such as marital satisfaction (e.g., Voydanoff, 2005), family satisfaction (e.g., Cardenas, Major, & Bernas, 2004), and family-related strain (e.g., Swanson & Power, 1999). Finally, the third category (domain-unspecific outcomes) has also been found to be related to both directions of work-family conflict; these outcomes include life satisfaction (e.g., Greenhaus, Collins, & Shaw, 2003), psychological strain (e.g., Kelloway et al., 1999), and somatic complaints (e.g., Peeters, de Jonge, Janssen, & van der Linden, 2004).

Among the work-related outcomes linked to work-family conflict, job satisfaction is the variable that has most frequently been studied (see the meta-analyses by Bruck et al., 2002) in diverse samples (Allen et al., 2000; Netemeyer, Boles, & McMurrian, 1996). Although there is debate about how the two directions of work-family conflict predict job satisfaction (Grandey, Cordeiro, & Crouter, 2005), several studies have shown that work-family conflict in both directions has a role in determining work dissatisfaction (Allen et al., 2000; Carlson, Grzywacz, & Kacmar, 2010; Perrewé, Hochwarter, & Kiewitz, 1999; Rode et al., 2007). More recently, some studies (Balmforth & Gardner, 2006; Boyar & Mosley, 2007; Gordon, Whelan-Berry, & Hamilton, 2007; Hill, 2005; Mauno, 2010; Nicklin & McNall, 2013) have instead considered the positive influences of the family and work relationship on job satisfaction (see the meta-analysis by McNall, Nicklin, & Masuda, 2010).

Since work-family research has been dominated by the role stress perspective, studying the benefits of multiple roles has been neglected. Although the benefits of multiple roles were already recognised in the 1970s (Marks, 1977; Sieber, 1974), the positive effects of the work-family interface has only recently begun to gain growing attention (Barnett, 1998; Rothbard, 2001; Ruderman, Ohlott, Panzer, & King, 2002). Several studies have introduced a perspective focusing on the construct of enhancement (Ruderman et al., 2002), which considers participation in multiple roles as a chance to implement opportunities and resources (Barnett, 1998) and perform enriching experiences (Rothbard, 2001). Labels such as ‘positive spillover’ (Barnett, 1998), ‘enrichment’ (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006; Rothbard, 2001), ‘enhancement’ (Ruderman et al., 2002), and ‘facilitation’ (Frone, 2003; Grzywacz & Butler, 2005; Hill, 2005) stress the positive consequences of relationships between work and family (Frone, 2003; Geurts & Demerouti, 2003). ‘Positive spillover’ describes experiences such as moods, skills, values, and behaviours transferred from one role to another (Carlson, Kacmar, Wayne, & Grzywacz, 2006). Positive spillover has recently enjoyed greater attention in the field of the work-family interface, with models on the topic continuing to be developed. According to ‘work-family enrichment’ theory, support and resources from one domain can enhance performance in others through instrumental (such as skills and money) and affective (positive moods and emotions) paths (Greenhaus & Powell, 2006). ‘Enhancement’ refers to the social and psychological resources acquired through participation in multiple life roles (Ruderman et al., 2002). As opposed to the role stress theory, the ‘role enhancement’ theory suggests that participation in multiple roles provides an individual with a greater number of opportunities and resources that can be used to promote growth and better functioning in other life domains (Barnett, 1998). It is based on the view that multiple role participation can lead to energy expansion (Marks, 1977), and will therefore provide individuals with enriching experiences (Rothbard, 2001).

In summary, research on work and family relationship has traditionally focused on the negative aspects of work-family conflict (Bellavia & Frone, 2005), but over the past 20 years many studies have also focused on the positive effects of work-family interface (Carlson et al., 2006; Frone, 2003; Greenhaus & Powell, 2006; Grzywacz & Butler, 2005; Hill, 2005; Ruderman et al., 2002). Frone (2003) articulated a multidimensional model of work-family balance incorporating work-to-family and family-to-work conflict and facilitation. The ‘work-family facilitation’ concept (Frone, 2003) asserts that participation in one domain is made easier by experiences, skills, and opportunities developed in another, in that participation in multiple roles provides contact with resources and experiences that contribute to personal realisation (Grzywacz & Butler, 2005).

Despite several international scales measuring the relationship between family and work domains (for example Frone et al., 1992a, 1992b; Geurts et al., 2005; Netemeyer et al., 1996), few are available in Italian, or they measure only the ‘bright side’ (Ghislieri, Martini, Gatti, & Colombo, 2011) or only the ‘negative side’ (Cortese, Colombo, & Ghislieri, 2010). We believe that it is necessary to integrate measurement tools in order to articulate a multidimensional model of work-family relationships that considers both negative and positive influences in the two directions, and is able to capture the complexity of the interaction between work and family roles (De Simone et al., 2014; Frone, 2003; Geurts & Demerouti, 2003; Wagena & Geurts, 2000).

Thus, the purpose of this study was to test the factorial structure and invariance of the work-family interface measure, developed by Kinnunen, Feldt, Geurts, & Pukkinen (2006) and adapted for Italian use (De Simone et al., 2014), which was designed to take into account positive and negative relationships between work and family demands in both directions. Our assessment was conducted in two different organisational contexts: a classic public administration and a public administration involved in a process of change management.

Organisational and structural changes in the workplace can reduce work-family conflict and increase working and family life fit (Kelly et al., 2014; Williams, 2001). Changes in working conditions and workplace policies can reduce work-family conflicts and associated inequality (ibid.). A study conducted in 2011 (Kelly, Moen, & Tranby, 2011) on 608 employees of a white-collar organisation demonstrated that organisational changes in the workplace positively affected work-family interference. The study highlighted the importance of implementing work management strategies that attempt to change the organisational culture to one in which the norm is flexibility as to when and where employees work. Flexible schedules do indeed generate less work-family conflict (Byron, 2005; Galinsky, Sakai, Wigton, & Summary, 2011; Kossek, Lautsch, & Eaton, 2006; Moen, Kelly, & Huang, 2008; Roeters, van der Lippe, & Kluwer, 2010) and a better work-life balance (Tausig & Fenwick, 2001). Hence, many organisations have implemented flexible working arrangements with the goal of supporting the balance between work and personal life (Anderson, Coffey, & Byerly, 2002; Kelly et al., 2011; Kossek et al., 2006). Several studies have shown the role played by support in managing work-family relationships (Kossek, Pichler, Bodner, & Hammer, 2011). In particular, managerial support, organisational time expectations, and career consequences associated with using work-family benefits have been shown to be related to work and family conflict (Thompson, Beauvais, & Lyness, 1999). A work-family culture that includes supervisory support, perceived negative career consequences, and organisational time demands was also found to affect work-family balance (Thompson et al., 1999). Negative career consequences and lack of managerial support are significant predictors of work and family conflict, even accounting for the effects of work schedule flexibility (Anderson et al., 2002). Organisational support for family issues helps to create a good work-family balance (Behson, 2002; Premeaux, Adkins, & Mossholder, 2007), while supervisors’ support has been shown to have a strong impact on family-work balance (Allen, 2001; Hammer, Kossek, Yragui, Bodner, & Hanson, 2009; Hill, 2005; Kossek et al., 2011; Lapierre & Allen, 2006). Organisational policies and benefits can reduce work-family conflict and improve organisational and individual outcomes (Thomas & Ganster, 1995). Formal and informal practices can create a supportive work environment and positively affect the work-family balance (Thomas & Ganster, 1995; Thompson et al., 1999). The work-family culture plays an important role in an employee’s well-being and work-family balance (see Mesmer-Magnus & Viswesvaran, 2006). Assuming that a family-friendly organisational culture positively influences the work-family interface (Eby et al., 2005), organisations should create an environment in which their employees can become more effective in both the work and family domains (Hall, 1990).

Confirmation of a four-factor model would demonstrate the existence of both positive and negative aspects on work-family and family-work interactions in public organisations either with or without a work-family balance orientation, and would support the use of a complex model when studying this topic (De Simone et al., 2014; Frone, 2003; Geurts & Demerouti, 2003; Wagena & Geurts, 2000).

The Present Studies

The main purpose of these studies were to investigate the psychometric properties of the Italian version of the Work-Family Interface Scale (WFIS; Kinnunen et al., 2006) and to test its multigroup invariance. In order to achieve this aim, an explorative factor analysis and a multigroup confirmatory analysis were applied (Byrne, 2008), based on the assumption that the questionnaire has the same theoretical structure and operates in the same manner in the studied groups. Furthermore, the concurrent validity of the features was assessed by examining their linear correlations with other measures validated in an Italian context: the Job Satisfaction Scale (Judge, Locke, Durham, & Kluger, 1998) and the Work-Family Interface assessed by a specific scale of the Organizational and Psychological Risk Assessment Questionnaire - OPRA (Magnani, Mancini, & Majer, 2009). These studies build on previous findings relating to this questionnaire (De Simone et al., 2014) that have demonstrated the utility of this measure in the assessment of organisational contexts.

Method

A total of 707 workers of public Italian administrations were recruited. We divided the employees in two samples, in order to carry out two studies; specifically, sample 1 was composed by 287 participants (M = 42.68 years, SD = 8.99, age range = 25-63, 45.22% women); sample 2 was characterised by 420 workers (M = 43.83 years, SD = 9.57, 47.20% women).

Participants

Study 1. Workers in the Study 1 have a seniority of about 17 years (M = 17.04, SD = 6.89). They worked an average of 35 hours per week (M = 34.67, SD = 8.84); 94.20% of participants have white-collar occupations (office workers); the remaining 5.80% performs other functions in the public administration. Among the participants, 33.85% are graduate, 66.15% have a secondary education. Almost 66% of participants have children (most commonly 2, range 0-4) (see Table 1).

Study 2. Data for the study 2 were collected from 420 public sector workers, with an average organisational seniority of 17.18 years (SD = 6.97). Specifically, participants were differentiated on the basis of their organisation: the first group worked in a classic Italian public administration (n = 237), the second in an Italian public administration undergoing a process of change management (n = 183). In terms of the organisations, the first group comprised task-oriented public administrations dealing with a broad range of administrative tasks and services, which had declared no specific interest in work-family balance issues. The second included organisations in the process of restructuring, among whose stated strategic goals was the creation of a work environment that was family-friendly and supportive of a work and family balance.

In the first organization there is 51.20% of women, in the second organization there is 42.30%. The mean age of workers in the first organization is 41.27 (SD = 9.91), while in the second organization it is 47.15 (SD = 17.55). The average weekly working hours are about 33 hours in the first organization (M = 33.16, SD = 9.54) and about 35 in the second one (M = 35.20, SD = 8.79). Almost two-thirds of the participants have a secondary school education (in Organization 1, 66%; in Organization 2, 70.7%). The percentage of clerks is over 90% in both organizations (in Organization 1, 92.30%; in Organization 2, 95.10%). Over 65% of participants have at least one child (Organization 1, 65.03%, Organization 2, 65.97%).

The descriptive statistics for all participants are presented in Table 1. Non-probability sampling was carried out, with participants being recruited on a voluntary basis.

Instruments and Procedure

Managers of the organisations were informed about the study and, after they had agreed to participate, all staff received a letter briefly describing the research. They were then informed of the study’s objectives through specific meetings with researchers, during which the procedures of the study were explained and the participants assured that their responses would remain confidential. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants.

In conducting the present research, ethical guidelines were followed. All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee, the Italian Association of Psychology (AIP), the American Psychological Association (APA), and the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its subsequent amendments. Our study received the Research Ethics Committee’s approval. Participation in the study was voluntary and the information provided was anonymous and confidential.

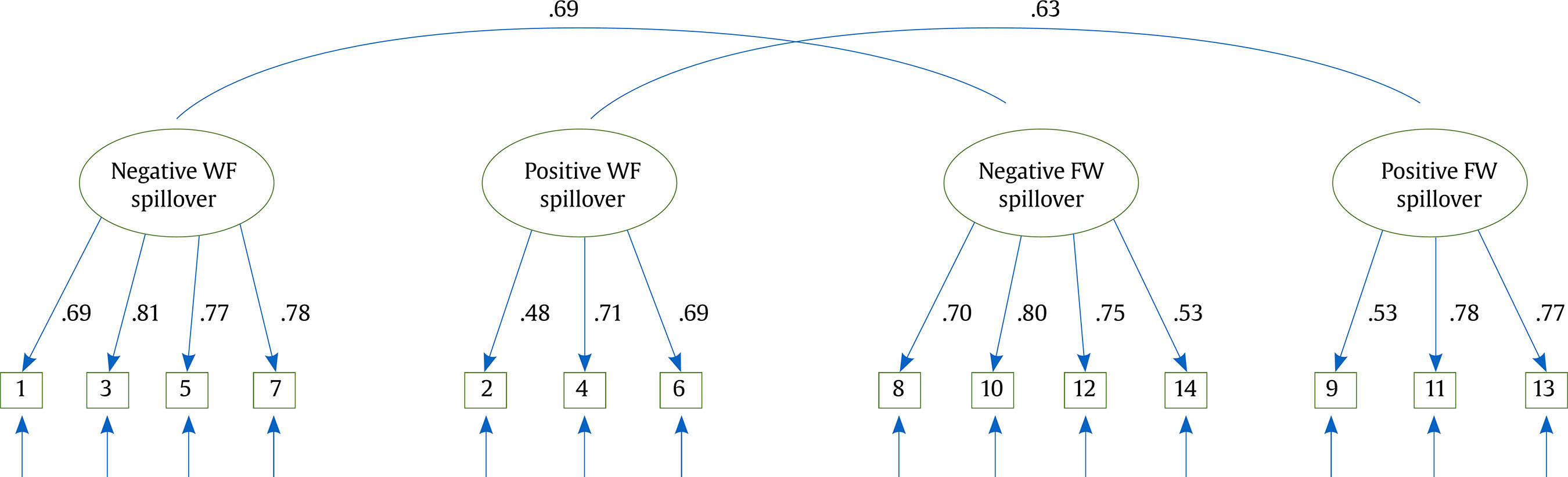

The Work-Family Interface Scale (Kinnunen et al., 2006) assesses positive and negative spillover between family and work in both directions. This questionnaire contains 14 items measured on a Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often) and covering four dimensions: the first dimension assesses negative work-to-family spillover (NEGWIF) through items 1-3-5-7, the second evaluates negative family-to-work spillover (NEGFIW) through items 8-10-12-14, the third measures positive work-to-family spillover (POSWIF) by way of items 2-4-6, and the fourth considers positive family-to-work spillover (POSFIW) using the items 9-11-13 (see Figure 1). The Work-Family Interface Scale (WFIS) in its Italian version can be found in the Appendix.

Note. Negative WF spillover = negative work family interface; positive WF spillover = positive work family interface; negative FW spillover = negative family work interface; positive FW spillover = positive family work interface.

Figure 1 Final Factor Structure of WFIS Questionnaire – Study 2.

Job satisfaction was measured using the Brief Overall Job Satisfaction measure II (De Simone et al., 2014; Judge et al., 1998). Participants’ perceived satisfaction with their current work was evaluated on a response scale of 1 to 7 (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree), on the basis of the following five items: “I feel fairly well satisfied with my present job”, “On most days I am enthusiastic about my work”, “Each day of work seems like it will never end”, “I really enjoy my work”, and “I consider my job rather unpleasant”.

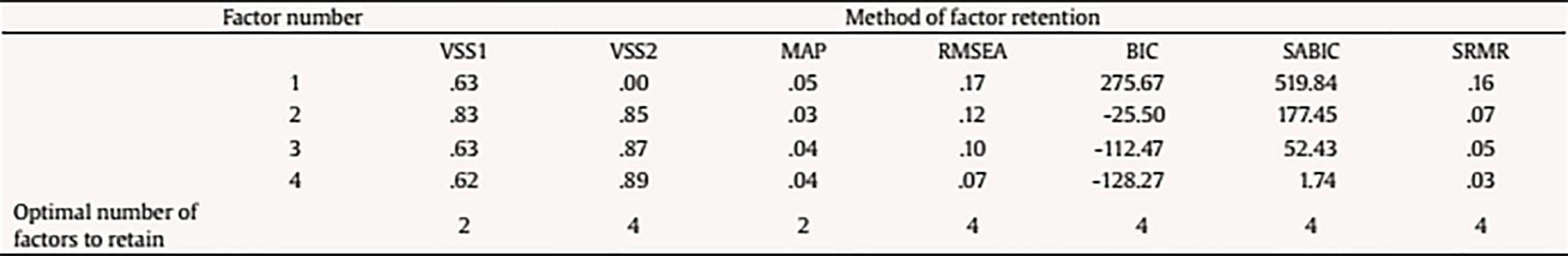

Table 2 Assessment of the Number of Factors to Retain in the Explorative Factor Analysis (EFA)

Note. VSS1 = very simple structure, complexity 1; VSS2 = very simple structure, complexity 2; MAP = minimum average partial test (MAP); RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; BIC = Bayesian information criterion; SABIC = sample size adjusted BIC; SRMR = standardized root mean square residual.

The work-family interface was assessed using a specific scale of the Organizational and Psychological Risk Assessment Questionnaire - OPRA (Magnani et al., 2009). OPRA is a multifactorial questionnaire used to assess work-related stress. It is structured in three parts (Risk Index, Inventory of Sources of Risk, and Mental and Physical Health) and evaluates different aspects of work experience on a five-point Likert scale (from never to always). The Work-Life Balance (WLB) Scale, included in the Inventory of Sources of Risk, comprises five items that assess the pressures from work to family and vice versa (e.g., “Relationships with family members and/or partners are problematic because of work”).

Data Analysis

Analyses were carried out using a multiple stage approach. In Study 1, we carried out the exploratory factor analysis (EFA), using the shiny package(Chi-Lin Yu & Ching-Fan Sheu. 2018) designed for R (R Core Team, 2017). In order to face the eminent problem related to determine the number of factors to retain in the EFA, we applied the following statistical methods: scree plot (Cattell, 1966), parallel analysis and quantile of parallel analysis (Horn, 1965), very simple structure complexity (VSS) (Revelle & Rocklin, 1979), Velicer’s minimum average partial test (MAP) (Velicer, 1976), RMSEA (root mean square error of approximation), BIC (Bayesian information criterion), and SRMR (standardised root mean square residual) (see Table 2). Then, to identify the factor structure underlying the Italian version of the WFIS questionnaire, the exploratory factor analysis was applied using the principal component analysis (PCA), whit the Oblimin rotation. We assessed the suitability of these data by the Kayser-Meyer-Olkin measure (KMO) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. We applied the Cronbach’s alpha to assess the internal consistency of each factor.

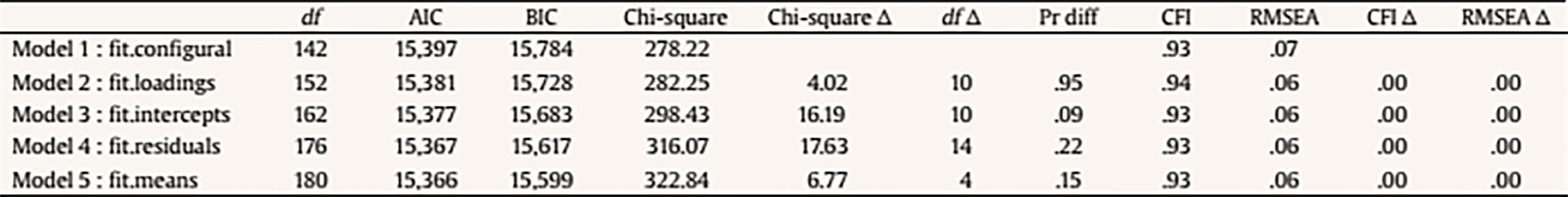

Then, in Study 2, the confirmative factor analysis (CFA) and the factorial invariance between the two organizations were evaluated to validate the results of the previous PCA. Indeed, the model highlighted by the PCA and hypothesised by Kinnunen et al. (2006) was applied (four correlated factors), in order to evaluate the fit in relation to the two groups of employees. The factorial invariance was assessed via multigroup confirmatory factor analysis (Byrne, 2008; Hirschfeld & Von Brachel, 2014), which makes it possible to simultaneously assess the data from different groups. This is achieved by constraining certain parameters to assume the same values in the samples. Using this procedure, measurement invariance can be assessed at different levels. A configural invariance indicates that the number of latent constructs and the patterns of factor loadings are analogous in the compared groups (see Table 5 - Model 1). A weak invariance implies that the previous conditions are satisfied and that there is metric invariance (i.e., the size of factor loading is comparable across the groups) (see Table 5 - Model 2). A strong invariance occurs when the previous requirements are satisfied and scalar invariance (i.e., the items’ intercepts are comparable across the groups) is achieved (see Table 5 - Model 3). A strict invariance is achieved when, in addition to the aforementioned conditions, residual variances are comparable across the groups (see Table 5 - Model 4). Finally, the last and most restrictive form of invariance implies that the means of the groups for each latent variable are also similar (see Table 5 - Model 5) (Hirschfeld & Von Brachel, 2014).

Table 5 Study 2 - Measurement Invariance Models

Note. AIC = Akaike information criterion; BIC = Bayesian information criterion; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation with confidence interval; CFI = comparative fit index; ∆ = differences in fit indices between the unconstrained baseline model and the stronger constrained models.

For each previously mentioned model the specific parameters were constrained to be equal across groups; the fit of each model was related to the strong measurement model of invariance. In order to decide on the invariance of measurement, changes in the fit indices were observed; specifically, the CFI and the ∆CFI were heavily used (∆CFI < .01 is the suggested cut-off point for deciding whether a more constrained model implies a considerable decrease in model fit with respect to a less constrained model) (Chen, 2007). We carried out confirmatory factor analyses (estimator ML) using R 3.4.1 (R Core Team, 2017); specifically, lavaan, semPlot, and semTools packages were applied (Epskamp, 2017; Jorgensen, Pornprasertmanit, Miller, Schoemann, & Rosseel, 2016; Rosseel, 2017).

Results

Study 1

Data from the first sample of 287 workers were examined with explorative factor analysis.

By the assessments of the above-mentioned multiple statistical criteria (scree plot, parallel analysis and quantile of parallel analysis, very simple structure complexity, Velicer’s minimum average partial test, RMSEA, BIC, and SRMR) (Chi-Lin Yu & Ching-Fan Sheu. 2018; Golino &Epskamp, 2017), we concluded that the number of optimal factors to retain in the WFIS was 4.

Then, we applied the principal component analysis (PCA) with Oblimin rotation (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy = .83, Bartlett’s test of sphericity chi-square = 1,749.11, df = 91, p < .0001). The four components explain 68.60% of the total variance and all items have a component load .30 or above (Table 3a). The assessment of the internal consistency was implemented by the application of Cronbach’s alpha (component 1, NEGWIF, negative work family interface, α = .87; component 2, POSFIW, positive family work interface, α = .83; component 3, POSWIF, positive work family interface, α = .66; component 4, NEGFIW, negative family work interface, α =.77)

Table 3a Item Descriptive Statistics. Results of Principal Component Analysis – Oblimin Rotation (component loadings and internal consistency) – Study 1 - Total Sample (N = 287)

Then, PCA was applied separately for men and women, to evaluate if the component structure remains stable in relation to the gender of the workers. For the subsample of men ((Table 3b) we applied the PCA with Oblimin rotation (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy = .82, Bartlett’s test of sphericity chi-square 964.39, df = 91, p < .0001). The solution explains 68.96 % of the total variance; component loadings were similar to the PCA applied in the total sample, confirming also the reliability of components (component 1, NEGWIF, α = .86; component 2, POSFIW, α = .80; component 3, NEGFIW, α = .64; component 4, POSWIF, α = .72). Likewise, for women, the PCA was carried out (Oblimin rotation, Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy = .81, Bartlett’s test of sphericity chi-square = 842.17, df = 91, p < .0001), highlighting the same solution of the men’s subsample (Table 3c). The total variance explained was 69.79%, the reliability was good for all components (component 1, NEGWIF, α = .87; component 2, POSFIW, α = .85; component 3, POSWIF, α = .66; component 4, NEGFIW, α = .72). Overall, the finding underlined a similar factorial structure for men and women.

Study 2

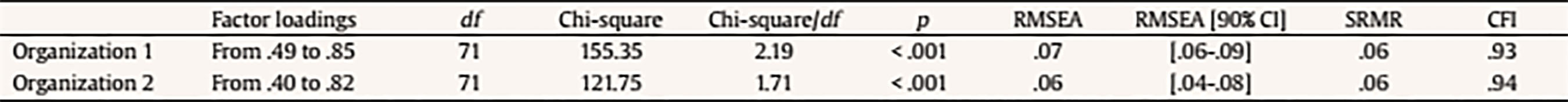

In the second study, confirmatory factor analyses (estimator ML) were applied separately for each group of employees; we examined the data fit in relation to the a priori model (four correlated factors) specified by the authors of the Work-Family Interface Scale (Kinnunen et al., 2006) and highlighted in the EFA. In order to assess the models, multiple indices were considered: ratio of chi square and its degrees of freedom, defined as being acceptable if it is below five (Wheaton, Muthen, Alwin, & Summers, 1977) and even better if below three (Schermelleh-Engel, Moosbrugger, & Müller, 2003); comparative fit index-CFI, for which higher than .90 is considered acceptable (Byrne, 2001); and, the indices root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and standardised root mean square residual (SRMR), for which lower than .08 is designated an adequate fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). The CFAs applied showed good fit indices for both groups (see Table 4), confirming the factor structure of the questionnaire.

Table 4 Study 2 - CFA for Each Participants’ Group

Note. RMSEA (90% CI) = root mean square error of approximation with confidence interval; SRMR = standardized root mean square residual; CFI = comparative fit index.

In the second step, we applied multigroup confirmatory factor analysis. This approach permits the measurement invariance of the scale to be assessed across groups of individuals that are expected to have the same levels of the latent construct (Byrne, 2008). Table 5 presents the fit indices of the nested CFA, applied in order to verify the invariance. The fit of the multigroup model is acceptable (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002); the differences in fit indices between the unconstrained baseline model and the stronger constrained models highlight a strict factorial invariance, confirming the validity and usefulness of this assessment instrument. Specifically, this evidence of invariance implies that the employees of both organisations conceptualise the work-family interface in the same way.

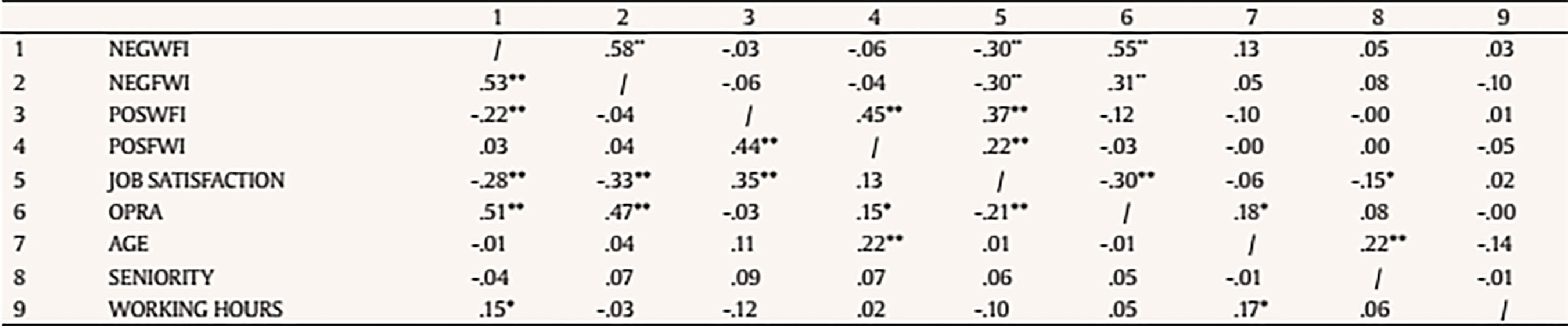

Additionally, linear correlations (Pearson’s r) between the assessed variables were computed, highlighting and confirming the relationships between the dimensions examined (Table 6a). Furthermore, applying the same correlations separately for men and women (Table 6b), we highlighted some interesting data. Both in the subsample of men and women we observed a significant positive correlation (p < .05, p < .001) between NEGFWI and NEGWFI (rm = .53, rw =.58); furthermore, in both subsamples, there is a significant positive correlation between POSWFI and POSFWI (rm = .44, rw = .58). Focusing on the correlations differing by gender, regarding the relationships between the scales of WFI questionnaire, only in men subsample there is a significant negative correlation between POSWFI and NEGWFI (rm = .44); the same variables are not correlated in the women sample. Observing the linear relationships between the scales of WFI questionnaire and the other dimensions inquired, we highlighted that only in women subsample there is a positive significant correlation between POSFWI and JOB SATISFACTION (rw = .22). Furthermore, only women show a significant positive correlation between OPRA and AGE (rw = .18), between AGE and WORK SENIORITY (rw = .22), a negative significant correlation between JOB SATISFACTION and SENIORITY (rw = -.15). In men’s subsample, we observed a positive significant correlation between AGE and POSFWI (rm = .22), OPRA and POSFWI (rm = .15); there is also a positive correlation between NEGWFI and WORKING HOURS (rm = .15). The correlations between JOB SATISFACTION and the scales of WFI questionnaire, OPRA and NEGWFI and NEGFWI, OPRA, and JOB SATISFACTION are analogous in men and women, as in the total sample.

Table 6a Pearson’s Correlation between Inquired Variables – Study 2 (total sample)

Note. NEGWFI = negative work family interface; NEGFWI = negative family work interface; POSWFI = positive work family interface; POSFWI = positive family work interface; OPRA = organizational and psychosocial risk assessment.

*p < .05 (2 tailed), **p < .01 (2 tailed).

Table 6b Pearson’s Correlation between Inquired Variables – Study 2 (men in the lower triangle/women in the upper triangle)

Note. NEGWFI = negative work family interface; NEGFWI = negative family work interface; POSWFI = positive work family interface; POSFWI = positive family work interface; OPRA = organizational and psychosocial risk assessment.

*p < .05 (2 tailed), **p < .01 (2 tailed).

Discussion and Conclusions

These studies were conducted within a theoretical framework that considered the complexity of interactions between work and family domains and analysed the effects of negative and positive work-to-family and family-to-work interfaces. The findings confirm the factorial structure and reliability of the questionnaire as devised by the authors (Kinnunen et al., 2006). In accordance with previous research (De Simone et al., 2014; Frone, 2003; Geurts & Demerouti, 2003; Wagena & Geurts, 2000), the results support the use of a multidimensional construct and four-factor model for studying this topic in public organisations, emphasising the importance of distinguishing between the four different dimensions when considering both negative and positive influences in the two directions (De Simone et al., 2014; Frone, 2003; Geurts & Demerouti, 2003) since these dimensions may have different antecedents and outcomes (Frone et al., 1992a, 1992b).

By the application of explorative and multigroup confirmative factorial analyses in the two studies, the questionnaire proved, respectively, their factor structure for men and women, then to be invariant between different groups of employees; taken together, these findings provide support for configural, metric, and scalar invariance across the groups of workers. The data demonstrates the existence of positive and negative aspects of work-to-family and family-to-work interactions both in public organisations oriented to a work-family balance and in traditional public organisations. Our results support the use in organisational studies of instruments such as the WFIS, which integrate both the positive and negative aspects of the work-family relationship (e.g., Barnett, 1998; Rothbard, 2001; Ruderman et al., 2002) and do not simply measure the ‘bright side’ (Ghislieri et al., 2011) or the ‘negative side’ (Cortese et al., 2010) only.

In addition, linear correlations between the scales of the questionnaire and related dimensions support the concurrent validity of this instrument, in the total sample and separately for men and women. Data analysis confirms the findings of previous studies that have shown negative correlations between negative aspects of work-family conflict in both directions and job satisfaction (e.g., Allen et al., 2000; Carlson et al., 2010; Perrewé et al., 1999; Rode et al., 2007), and a positive correlation between positive aspects of work-family relationship and job satisfaction (e.g., Balmforth & Gardner, 2006; Boyar & Mosley, 2007; Gordon et al., 2007; Hill, 2005; Mauno, 2010; Nicklin & McNall, 2013).

Research on the work-family interface is linked to changes in society, especially the increase in dual-earner couples and continuous modifications in family and working life. Work and family balance will continue to constitute a challenge in the future and will be central to further organisational studies, in terms of both negative and positive aspects, antecedents and consequences. Future research should use this instrument to gain a better understanding of the associations between family and work, and to plan actions and interventions in organisations.

This study has both extended our knowledge of work and family relationships and confirmed the importance of monitoring the work-family interface in order to improve job satisfaction. Given the validity and reliability of the WFIS in Italian contexts, this tool can be used to monitor positive and negative relationships between work and family in organisations, as they have a significant impact on various outcomes (Allen et al., 2000; Amstad et al., 2011; Ford et al., 2007), such as work-related, family-related, and domain-unspecific outcomes (Amstad et al., 2011; Bellavia & Frone, 2005). In particular, measuring the four dimensions of the work-family interface reliably and repeatedly over time would allow prevention and intervention actions to be planned.

Nevertheless, some limitations of the present research deserve to be mentioned. One potential weakness might be related to the (non-probability) sampling strategies applied; in other words, to the fact that only a single geographic area was used. Overall, the four-factor model derived from the 14-item Work-Family Interface appeared to fit the data well in an Italian context, showing invariance between two groups of workers belonging to different organisations.

In summary, this questionnaire could be a suitable research instrument for psychologists and researchers interested in capturing the complexity of relationships between work and family domains but who reject a reductionist approach. We consider this instrument to be capable of revealing the complexity of the interaction between work and family roles and, in our opinion, it should be the framework for future organisational studies seeking to clarify the specific nature of these interactions.