Schizophrenia is a serious, and often lifelong mental disorder characterized by the presence of positive psychotic symptoms, negative psychotic symptoms and neurocognitive symptoms that seriously affect the quality and functioning in different areas of these people's lives (Tomotake, 2011). Neurocognition impairments in schizophrenia are related to both the development and the prognosis of the disease, affecting up to 80% of people with this disease (Addington et al., 2017). Within neurocognition, processing speed (PS) and sustained attention (SA) are of special importance since they can interfere with the development of other domains of neurocognition. PS and SA are basic cognitive processes underlying more complex domains such as memory, working memory, and executive functioning (Agnew-Blais & Seidman, 2013; Rodríguez-Sánchez et al., 2007). Thus, impairments in PS or SA result in greater difficulties in daily activities that require complex cognitive processes such as using transportation (e.g., understanding public transportation schedules, using maps), financial management (e.g., using ATMs or implementing a budget), and occupational functioning (e.g., assessed through role-play tasks; Shi et al., 2013). Over the last two decades, several meta-analyses have highlighted pronounced impairments in PS and SA in people with schizophrenia (Dickinson et al., 2007; Heinrichs & Zakzanis, 1998; Schaefer et al., 2013). Results of these meta-analyses were based on a heterogenous collection of neurocognition tests, since the use of a consensus battery for cognitive assessment in schizophrenia is a relatively recent implementation (Dickinson et al., 2007; Schaefer et al., 2013). At present, however, interest in PS and SA impairments has led to growing evidence that slow processing affects personal, social, and occupational functioning in schizophrenia (Bezdicek et al., 2020; Sánchez et al., 2009), and other important processes such as effective problem solving (Revheim et al., 2006) and social skills (Harvey et al., 2009). Along these lines, cognitive rehabilitation studies in people with schizophrenia demonstrate a relationship between improved PS and improved global functioning (Peña et al., 2018). This makes sense if we consider the importance of PS when it comes to capturing, processing, and retrieving relevant information needed for everyday tasks such as having a conversation, solving an interpersonal difficulty, providing answers to a problem, or generating efficient solutions (Lindenmayer et al., 2017).

In addition to impairments in neurocognition, meta-analyses have also demonstrated marked impairments in social cognition (SC) in schizophrenia (Savla et al., 2013), with different effect sizes due, in part, to methodological heterogeneity across studies, an issue that has thus far received more attention in the field of neurocognition. Despite this methodological heterogeneity, there is a strong established relationship between impairment in SC and impaired functioning in schizophrenia (Fett et al., 2011; Halverson et al., 2019). Importantly, SC is an important determinant across different domains of functioning including community functioning (e.g., independent living, social behavior, occupational functioning), social skills, and social problem solving (Couture et al., 2006; Irani et al., 2012).

Along these lines, there is an increasing focus in the field on understanding the structure and relationships between neurocognition, SC, and functioning (Halverson et al., 2019). There is some evidence that SC is a potential mediator of the relationship between neurocognition and functioning, with SC explaining up to 20% of variability in functioning (Schmidt et al., 2011). This mediating effect of SC has been found in the relationship between functional outcomes and different cognitive domains including: verbal and visual memory (Horton & Silverstein, 2008), attention and vigilance (Meyer & Kurtz, 2009), composite neurocognition with cross-sectional study designs (Addington et al., 2010; Addington et al., 2006; Bell et al., 2009; Couture et al., 2011; Gard et al., 2009; Vaskinn et al., 2008; Vauth et al., 2004), and composite neurocognition with longitudinal study designs (Brekke et al., 2005).

To our knowledge, the relationship between PS, SA, SC, and functioning has not been studied through careful mediation analysis, an approach necessary for a comprehensive understanding of how these different domains relate to potential treatment implications. A similar conceptual approach was applied to measures of early visual processing and vigilance measures (Meyer & Kurtz, 2009) using an apprehension amplitude task (Horton & Silverstein, 2008), a visual masking task (Rassovsky et al., 2011; Sergi et al., 2006), or a general movement task (Brittain et al., 2010), where an indirect effect of visual processing and attention on functioning has been observed through CS in people with schizophrenia. However, few studies to date have attempted to precisely elucidate the magnitude and direction of PS, SA, SC and their influence on daily functioning.

Our hypotheses are: a) clinically stable people diagnosed with schizophrenia perform poorer than healthy controls in PS, SA, and SC (H1); b) higher levels of PS and SA deficits are associated with worse levels of functioning (H2), although the total effect is influenced by the effect of PS and SA deficits on SC (i.e., that PS and SA predicts SC in people with schizophrenia (H3) which in turn predicts worse functioning (H4) in these people).

Method

Participants

Ninety clinically stable outpatients between 18 and 65 years of age with a diagnosis of schizophrenia according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5th Edition (APA-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and 100 people without a psychiatric diagnosis (i.e., healthy controls) participated in this study. Sample size was estimated taking into account previous data on sample size provided by 1) similar healthcare studies with comparable methodological criteria (Montag et al., 2011; van Hooren et al., 2008); and 2) statistical criteria related to keeping an appropriate ratio of number of observations per variables and paths of interest (10:1). To determine clinical stability, participants were required to have a minimum period of four weeks without changes in psychopharmacological treatment, in accordance with previous studies (Lindenmayer et al., 2017). Exclusion criteria included any current comorbid psychiatric disorder except tobacco or caffeine use disorder, extrapyramidal symptoms with pharmacological origin according to the Simpson-Angus Akathisia Scale (SAS; score > 3), intellectual disability (Intellectual Quotient [IQ] < 70), neurological disorder, history of brain injury or severe medical illness, and functional illiteracy. Psychiatric comorbidity was assessed through clinical interviews and chart reviews. The healthy control group consisted of people without: current Axis I diagnoses, neurological disorder, history of brain injury or severe medical illness, and functional illiteracy. The healthy control group was not significantly different in sex, age or education level compared to people with schizophrenia.

Instruments

Clinical Symptoms

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Kay et al., 1989), Spanish version (Peralta-Martín & Cuesta-Zorita, 1994), assessed clinical symptoms. The Spanish version of the PANSS previously demonstrated reliability of .71 (positive subscale), .80 (negative subscale), and .56 (general subscale; Peralta-Martín & Cuesta-Zorita, 1994).

The Simpson-Angus Scale - Short Version (SAS; Simpson & Angus, 1970), Spanish translation (Calvo-Gómez et al., 2006), assessed extrapyramidal symptoms. The SAS has adequate test-retest reliability, interrater reliability, concurrent validity, and sensitivity values above .80.

Processing Speed

Three instruments included in the MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB; Nuechterlein et al., 2008), Spanish translation (Rodriguez-Jimenez et al., 2012), were administered to assess PS. The Trail Making Test, Part A (TMTa; Partington & Leiter, 1949) is a brief, timed pencil-and-paper test that assesses visual scanning and visuomotor tracking and psychomotor slowing, with a test-retest reliability of .76 (Shi et al., 2015). The Animal Naming task (Benton & Hamsher, 1978) is a verbal fluency test that evaluates the spontaneous and rapid production of words that can be considered within the category "animals" for 60 seconds. The Intraclass Correlation demonstrated test-retest reliability of .78 (Shi et al., 2015). The Symbol Encoding subtest from the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS; Keefe, 1999) is a 90 second test that requires participants to write numbers corresponding to a set of symbols as quickly as possible. This instrument has demonstrated a good concurrent validity (r > .70) (Segarra et al., 2011).

Sustained Attention

The Continuous Performance Test Identical Pairs (CPT-IP; Rapisarda et al., 2014) from the MCCB assessed SA. The CPT-IP is a computerized measure of SA that involves detecting a series of digits that appear briefly on a computer monitor. The CPT-IP demonstrates good psychometric properties, with a test-retest reliability of .89 (Shi et al., 2015).

Social Cognition

Two measures, a static facial emotion task and a dynamic audiovisual task, assessed SC. The Penn Emotion Recognition Test (ER40; Gur et al., 2002) asks participants to correctly identify the corresponding emotion presented in 40 photographs among five options: happiness, sadness, anger, fear, or neutral emotional expressions. The ER40 has previously demonstrated a reliability of .71 (patients) and .679 (controls) with expert consensus to assess emotional processing in schizophrenia (Pinkham et al., 2018). Correct performance (i.e., total number of correctly identified emotions) and response time (i.e., time spent to complete each item; Cornacchio et al., 2017) were recorded as outcomes.

The Movie for the Assessment of Social Cognition (MASC; Dziobek et al., 2006), Spanish validation (Lahera et al., 2014), also assessed SC. The MASC is a 45-minute audiovisual task that assesses global SC. The MASC produces four SC scores: a hit score (i.e., correct description of character mental state), and three types of errors; hypermentalization (excess attribution in the ability to mentalize), hypomentalization (deficit attribution in the ability to mentalize) and non-mentalization (absence of attribution in the ability to mentalize). The MASC has demonstrates optimal internal consistency (.86) and good test-retest realiability (Lahera et al., 2014). For this study, both performance scores (hits and errors) and response time per item were recorded.

Functioning

The Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP; Morosini et al., 2000), Spanish validation (García-Portilla et al., 2011), was administered by trained raters to assess functioning. The PSP has demonstrated a reliability of .79 in people with schizophrenia (Brissos et al., 2012).

Procedure

Participants in this study were recruited from June 2016 to August 2017 through a consecutive and intentional sampling for the schizophrenia group and an intentional type for the control group. People with schizophrenia enrolled as outpatients of the Alcalá de Henares Hospital (Madrid, Spain) participated in this study. Thirty-six people refused to participate in the study. A trained clinical psychologist administered the cognitive and social cognitive tests and completed measures of global functioning for approximately 60 minutes at the mental health center. The control group were healthy volunteers recruited from the community through advertisements and followed the same evaluation procedure, except for the clinical variables and functionality. The Ethics Committee at the Príncipe de Asturias University Hospital approved the study protocol (OE 08/2016). The present study complied with the ethical standards of the responsible human experimentation committee in accordance with the World Medical Association and the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent to voluntarily participate in the study.

Data Analysis

Data were explored prior to any statistical treatment to assess variables' distribution, normality and homoscedasticity, and to check for potential outliers (not detected). Mean and standard deviations were calculated for continuous data and percentages were provided as descriptives for categorical data. To test for differences between groups, t- or non-parametric tests were used according to the distribution of the variables, and associated effect sizes were calculated using the standardized regression coefficient β.

Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMMs) using quasi-likelihood estimation were fitted to assess the relative effect of clinical, PS, and SA, on SC (both groups) and on functioning (schizophrenia group only). GLMMs were selected based on the distribution of response variables which did not meet the assumption of normality needed for standard linear modeling. Use of GLMMs also allowed for inclusion of random sources of variation (i.e., variability associated with each individual was treated as a random effect). All statistical analyses were carried out by using the R software (R core Team, 2020). For GLMMs we used the glmm. PQL function of the MASS package.

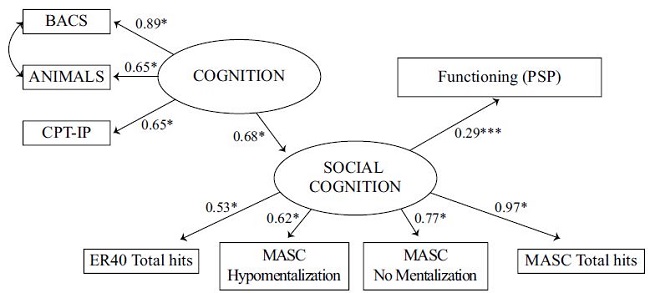

To evaluate the hypothesis that SC is a mediator in the association between PS, SA, and functioning in people with schizophrenia, we used Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), an extension of regression and path analysis. SEM can be used to test multivariate hypotheses and allows for the inclusion of latent variables (Shipley, 2016), which is especially pertinent in studies of psychiatric health (van Rooijen et al., 2019). In this study, two SEM models were evaluated: 1) a basic model, which hypothesized the existence a direct and positive effect of cognition (i.e., a latent variable composed of the PS and SA variables) on functioning (i.e., PSP); 2) a mediation model, which hypothesized that there is a positive effect of cognition on SC (specified as a latent variable composed of ER40 Total Hits, MASC Total Hits, MASC Hypo Mentalization and MASC No Mentalization), and a positive effect of SC on functioning. This second model analyzed the possible indirect effect of PS and SA on functioning with SC as a mediator. We could not test the potential effect of PS and SA and the potential effect of SC on functioning simultaneously due to the high multicollinearity among the whole set of variables. To correct for non-normal distribution of variables, Diagonally Weighted Least Squares (DWLS) estimation was used, a robust alternative for analyzing data that do not adequately fit a normal distribution (Mindrila, 2010). Correlation analysis and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) were conducted to ensure that the variables included in the latent variables were not redundant and sufficiently informative. Therefore, to avoid redundancy in the models, TMTa was not included in the latent variable “Cognition”, given the high negative correlation (close to 1) with both BACS and ANIMALES. In line with this, MASC Hyper Mentalizacion and Time per item in the test ER40 and MASC were excluded from the model due to low factor loading weights. All the variables finally considered in the SEM added significant information to their respective latent constructs (factor loading for every item was 0.5 or higher). Model fit was assessed according to a variety of indices typically used in SEM: the model chi-square (X2) goodness-of-fit test, which indicates a good fit with a p-value greater than .05 (Shipley, 2016); the comparative fit index (CFI) and the Tucker Lewis index (TLI), which indicate a good fit with values greater than .90 (Fan et al., 1999; Byrne, 1994); the Root Mean Square of Approximation (RMSEA) and a Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), which are commonly assumed to indicate a good fit with values of less than .08 (Streiner, 2006). CFA and SEM analyses were conducted using the lavaan package (v. 6.0-7) of R. Missing data were handled with the default option in lavaan, which is listwise deletion (final N=86).

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

Demographic and clinical characteristics between groups are shown in Table 1. Healthy controls had sociodemographic characteristics similar to the schizophrenia group. In general, people with schizophrenia exhibited impaired performance compared with healthy controls on all SC and cognition outcomes including PS (TMTa, Animals, BACS), SA (CPT-IP), emotion recognition (ER40), and global SC (MASC), with effect sizes ranging from β = -0.53 to β = 0.95 (see Table 1).

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Participants (N = 190).

| Schizophrenia Group (n = 90) | Healthy Control Group (n = 100) | Mean Dif. | p | β | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | (%) | N | (%) | ||||

| Female | 22.0 | 24.4 | 37.0 | 37.0 | 1.9 | .061 | |

| Ethnicity, % white | 90 | 100 | 100 | 100 | - | - | |

| Level of education | |||||||

| No formal education | 2.0 | 2.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | -1.4 | -158 | |

| Primary | 37.0 | 41.1 | 28.0 | 28.0 | -1.9 | 0.59 | |

| High school | 4.0 | 44.4 | 53.0 | 53.0 | 1.2 | .241 | |

| University | 11.0 | 12.2 | 19.0 | 19.0 | 1.3 | .199 | |

| Marital status | |||||||

| Never married | 68 | 75.6 | 54 | 54 | -3.2 | .002 | |

| Currently married | 16 | 17.8 | 38 | 38 | 3.2 | .002 | |

| Ever married | 6 | 6.6 | 8 | 8 | -0.4 | .726 | |

| Residential status | |||||||

| Alone | 12 | 13.3 | 18 | 18 | 0.9 | .381 | |

| Parental | 53 | 58.9 | 24 | 24 | -5.2 | .000 | |

| Conjugal | 20 | 22.2 | 58 | 58 | 5.4 | .000 | |

| Sheltered living | 5 | 5.5 | 0 | 0 | -2.3 | .203 | |

| Employment status | |||||||

| Employment | 16 | 17.8 | 80 | 80 | 10.9 | .000 | |

| None | 22 | 24.4 | 12 | 12 | -2.2 | .028 | |

| Pensionary | 52 | 57.8 | 8 | 8 | 8.7 | .000 | |

| M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| Age (y) | 44.1 | 9.7 | 41.5 | 12.1 | -1.7 | .097 | |

| Age of illness onset (y) | 27.3 | 9.2 | |||||

| Illness duration (y) | 16.9 | 8.7 | |||||

| Hospital admissions | 2.0 | 2.5 | |||||

| Antipsychotic dose (median mg. equivalents of olanzapinea) | 10.0 | ||||||

| Psychiatric symptoms | |||||||

| PANSS Positive | 9.8 | 3.2 | - | - | - | - | |

| PANSS Negative | 10.1 | 3.1 | - | - | - | - | |

| PANSS General | 20.4 | 4.5 | - | - | - | - | |

| PANSS Total | 40.4 | 9.4 | - | - | - | - | |

| PSP Functioning | 53.6 | 15.4 | - | - | - | - | |

| Processing Speed | |||||||

| BACS | 34.9 | 13.8 | 51.1 | 12.1 | 8.6 | <.001 | -0.070 |

| Animals | 18.4 | 6.3 | 24.3 | 6.6 | 6.3 | <.001 | -0.835 |

| TMTa (sec.) | 42.5 | 22.6 | 25.9 | 1.5 | -6.5 | <.001 | 0.856 |

| Sustained Attention | |||||||

| CPT-IP (2 digit) | 2.8 | 1.1 | 3.7 | 0.6 | 6.6 | <.001 | -0.871 |

| Social Cognition | |||||||

| ER40 Total Hits | 29.2 | 4.5 | 32.0 | 3.2 | 3.7 | <.001 | -0.532 |

| ER40 Time/item (sec.) | 3.5 | 5.0 | 2.1 | 1.6 | -4.0 | <.001 | 0.571 |

| MASC Total Hits | 20.9 | 7.1 | 29.9 | 5.3 | 9.3 | <.001 | -1.126 |

| MASC Hypomentalization | 10.8 | 4.4 | 5.3 | 2.8 | -7.3 | <.001 | 0.947 |

| MASC Hypermentalization | 7.2 | 3.2 | 7.3 | 3.1 | 0.8 | .849 | |

| MASC No Mentalization | 5.9 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 2.0 | -7.3 | <.001 | 0.947 |

| MASC Time/item (sec.) | 13.6 | 4.7 | 9.8 | 2.9 | -6.7 | <.001 | 0.948 |

Note:aLeucht et al. (2015); statistically significant p-values (p<.05) highlighted in bold; t-tests used as significance tests for the sociodemographic variables and onset and duration of ilness; Mann-Whitney U tests used as significance tests for the variables: Processing speed (BACS, animals and TMTa), sustained attention (CPT-IP: Dprime 2 digits), emotion recognition (ER40), and global social cognition (MASC).

Effect sizes estimated for the hypothesis testing between groups: using the standardized regression coefficient (β) with negative values indicating that the mean is lower in the schizophrenia group and positive values indicating that the mean is higher in the schizophrenia group.

Processing Speed, Sustained Attention, Social Cognition, and Functioning

Table 2 shows the relationships between PS, SA and SC across groups. In the schizophrenia group, PS was associated with both SC outcomes (ER40 and MASC), in terms of performance and response time. In the schizophrenia group, better PS performance was associated with more accurate and faster performance on measures of SC. Likewise, faster performance on the MASC test was associated with higher hit scores. SA was only significantly related to emotion recognition; no significant relationships were observed on the MASC test or on response times in SC. In contrast, in the healthy control group, SA was significantly related to SC and PS was significantly associated with MASC response time, but not with MASC performance. In the schizophrenia group, better performance on PS outcomes were associated with better global functioning and occupational functioning but no significant associations were observed between functioning and SA (see Table 2). In the reduced statistical models, a significant effect of SC (MASC; t = 2.23, p = .027) on functioning was detected.

Table 2. Relationships Between Social Cognition (MASC and ER40), Processing Speed, Sustained Attention and Functioning.

| Processing Speed | Attention | Time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BACS | TMTa | Animals | CPT-IP | ER40 | MASC | |

| Schizophrenia (n = 90) | ||||||

| ER40 | 1.17 (.264) | -0.7 (.488) | 2.2 (.028) | 3.2 (.002) | 0.0 (.985) | - |

| Time ER40 | -0.1 (.956) | 0.9 (.355) | -2.1 (.042) | -0.1 (.927) | - | - |

| MASC | 0.8 (.435) | -1.9 (.056) | 3.3 (.002) | 1.3 (.196) | - | -2.2 (.028) |

| Time MASC | -1.9 (.054) | 1.3 (.184) | -2.9 (.004) | 0.7 (.481) | - | - |

| PSP | 2.6 (.010) | -2.3 (.025) | 0.4 (.689) | 1.7 (.082) | - | - |

| PSP Occupational | -3.3 (.002) | 2.6 (.011) | -0.0 (.979) | -1.9 (.060) | - | - |

| Healthy Controls (n = 100) | ||||||

| ER40 | 0.5 (.612) | 0.1 (.910) | 0.1 (.845) | 0.7 (.484) | 0.3 (.755) | - |

| Time ER40 | 0.9 (.340) | -0.1 (.911) | 0.1 (.921) | 1.0 (.317) | - | - |

| MASC | 1.2 (.226) | -1.1 (.235) | 1.9 (.052) | 2.9 (.004) | - | 0.8 (.421) |

| Time MASC | -3.5 (.001) | 0.8 (.422) | -2.0 (.046) | 0.1 (.878) | - | - |

Note:Results of the GLMMs presented for each of the predictor variables: 1) processing speed (BACS, TMTa, and Animals), 2) sustained attention (CPT-IP: 2-digit Dprime); and the response variables: 1) emotion recognition (ER40), 2) global social cognition (MASC), 3) emotion recognition response time (ER40), 4) global social cognition response time (MASC), 5) functioning (PSP), and 6) occupational functioning (PSP).

In all cases, a Poisson distribution of the error (link function “log”) has been assumed.

t-statistics and corresponding p-values (in parentheses) are presented in each cell. Statistically significant p-values (p < .05) are highlighted in bold.

Social Cognition as a Mediator Between Processing Speed, Sustained Attention and Functioning

The SEM models (i.e., basic model and mediation model) demonstrated good model fit to the study data (see Figures 1 and 2 for model results and fit indices). In the basic model (Figure 1), PS and SA explained 9.6% of the variance in functioning (β = 0.32, p = .03), with a larger effect size for PS (BACS), with respect to SA tests (see Figure 2 for all the factor load weights). In the mediation model (Figure 2), SC - more strongly represented by the MASC test (β = 0.97; see Figure 2 the rest of factor load weights) - explained 8,4% of the variance in functioning (β = 0.29, p = .000). In turn, PS and SA accounted for 46% of the variance in SC (β = 0.68, p <.001), with the BACS constituting the largest effect size.

Figure 1. Basic Model Estimating the Relationship Between Processing Speed, Sustained Attention and Functioning in the Schizophrenia Group (n = 90).

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to better understand the relationships between PS, SA, SC, and functioning in schizophrenia. To this end, relationships between these domains were examined with a basic model investigating the influence of PS and SA on functioning and a mediation model with SC as the mediator. Results of this study confirmed the role of SC as a mediator of the relationship between PS, SA and functioning. When SC was included as a mediator, the percentage of explained variance in global functioning slightly increased with respect to the basic model. These data are consistent with previous studies indicating that SC explain between 7% and 80% of the variance in functioning when included as a mediator (Schmidt et al., 2011; Addington et al., 2010), which is a relevant result regardless of the level of significance (using the threshold of p <.05) of those paths (Hurlbert et al., 2019).

Results of the SEM models highlighted PS as the most informative neurocognition process in relation to functioning (BACS; β = 0.90) and SC (BACS; β = 0.89). The ANIMALS subtest showed a smaller strength of relationship than the BACS subtest. Our results support the idea that SC and functioning are more related to the psychomotor aspects of PS than to verbal fluency (more related to memory). It is worth noting that, despite their level of significance, these effect sizes are higher than those reported in previous SEM studies that evaluated the mediating role of SC with different neurocognition domains, such as working memory (β = 0.68) or verbal memory (β = 0.79; Vauth et al., 2004). The most explanatory SC outcome for functioning was the MASC test (β = 0.97), in line with previous studies (Horton & Silverstein, 2008; Fett et al., 2011).

At a conceptual level, our results suggest that impaired PS and SA have an important influence on SC, which is already impaired in schizophrenia (Dickinson et al., 2007). Impairments in domains of neurocognition and SC, in turn, interfere in both a synergistic and summative way in the daily functioning of people with schizophrenia. These findings are consistent with a small but growing literature of research (e.g., early mediation studies with early visual processing tests [Brittain et al., 2010; Horton & Silverstein, 2008; Rassovsky et al., 2011; Sergi et al., 2006], more recent studies with early psychosis [Ayesa-Arriola et al., 2016], and with chronic schizophrenia [Torio et al., 2014; Tsotsi et al., 2015]).

A recent study carried out with the MASC test also supports the finding that PS is an influential neurocognition domain for SC performance (Andrade-González et al., 2021). Previous studies have found similar effects with different neurocognition domains such as working memory, episodic memory, attention, problem solving, and executive functioning (Catalan et al., 2018; Sjølie et al., 2020; Thibaudeau et al., 2019). A potential explanation for different findings across studies is the lack of homogeneity in tests of SC. Heterogeneity of SC assessment makes it difficult to compare results across studies. In the present study, the finding that global SC was a better fit to the mediation model than emotion recognition may be because the dynamic audiovisual format of the MASC better reflects daily performance and functioning. The MASC, in contrast to the use of static photographs of emotional expression in the ER40, may demonstrate more ecological validity (e.g., representation of social settings through changing stimuli similar to real life occurrences).

In general, people with schizophrenia had more impaired performance on PS, SA, and SC outcomes compared with healthy controls, which is consistent with previous research (Savla et al., 2013; Schaefer et al, 2013). The strong relationship observed between PS and SC in the schizophrenia group was not replicated in the healthy control group which is in contrast to previous studies (Deckler et al., 2018). Results of the present study also demonstrated significant relationships between SC performance and response times demonstrated with the MASC test; people with schizophrenia who were slower to identify mental states also made more mistakes, consistent with study hypotheses. Relatedly, SA was only associated with emotion recognition in the schizophrenia group, while in the healthy control group SA was only associated with MASC performance. These findings support previous work highlighting the importance of attention in facial emotion recognition (Couture et al., 2011) and suggest cognitive domains may be distinct in their effects depending on the task and the characteristics of the subject (e.g., the more demanding the SC tasks is for an individual, the greater the involvement of specific cognitive processes such as PS).

The results of the present study should be considered within the context of its limitations and strengths. A main strength of this study is the comprehensive clinical and cognitive evaluation (e.g., use of consensus measures for both neurocognition and SC) of a consecutive and representative inclusion of outpatients with schizophrenia and a healthy control group. In our study, to assess PS and SA, we used tests included in the consensus neuropsychological battery recommended by the research group for the improvement of cognition in schizophrenia of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (Nuechterlein et al., 2008). In this line more recent studies have also proposed more current neurocognitive batteries, such as the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB) that allow measuring the relationship between information processing and global functioning adequately in people with schizophrenia (Barnett et al., 2010). Another main strength of this study is the use of a dynamic audiovisual SC task (i.e., MASC), which may be more representative of real-world social interactions where rapid changes in emotional and cognitive processing are key elements.

One limitation of the present study is the assessment of functioning using a single score (i.e., PSP general score). A thorough evaluation of each of the subdomains of the PSP in the schizophrenia and healthy control group may provide a more nuanced understanding of the relationships between PS, SA, SC, and specific domains of functioning. However, the aim of this study was focused on a comprehensive understanding of the relationship and structure between PS, SA, SC and global functioning in people with schizophrenia (versus domains of functioning). A second limitation of the present study is potential effects from different pharmacological treatments in the schizophrenia group. However, meta-analyses have addressed potential pharmacological effects and found that psychotropic medications do not appear to amplify PS (Schaefer et al., 2013) or emotional perception impairments (Kohler et al., 2009).

To our knowledge, this is the first study that specifically analyzes the relationship between PS, SA, and functioning, with SC as a mediator. Findings of the present study demonstrating strong relationships between these domains with SC as a mediator makes ecological sense considering the quick and dynamic nature of social situations in everyday life, where both accuracy and speed in emotional processing are imperative (Hogarty et al., 2006; Peña et al., 2018). In people with schizophrenia, difficulties in PS may magnify impairments in identifying and processing a large number of socioemotional stimuli.

The relationships observed in the present study have clear implications for clinical practice. Impaired PS and consequential increased cognitive effort to process information in people with schizophrenia can compound SC impairments (e.g., difficulty identifying mental states), and may lead to attention and memory failures, motivational loss, or communication conflicts due to interpretation errors. Thus, people with schizophrenia may experience social interactions more negatively which can lead to feelings of low self-efficacy, more impaired social competence, and ultimately increased social isolation. However, our findings indicate that cognitive rehabilitation may be a compelling intervention to combat this negative social interaction cycle. As proposed by Cassetta et al. (2018), cognitive rehabilitation targeting PS may have long-term benefits on SC and psychosocial functioning in people with schizophrenia. The strong relationships demonstrated in the present study between PS, SA, SC, and functioning, and the difficulties observed in other studies in improving functioning when targeting only neurocognition, highlights the need to include both SC and neurocognition as intervention targets within functional recovery programs. In this way, our results support the empirical evidence demonstrated by multimodal treatment programs (e.g., Integrated Psychological Therapy [Brenner et al., 1994]) that address the multiple affected areas in psychosis (Fonseca et al., 2021). The present study also suggests a future direction with respect to the assessment of SC. The use of dynamic audiovisual stimuli in the MASC may be a better proxy for real world functioning than static stimuli presented in most SC assessments and thus represents a promising future direction for how to assess SC with improved ecological validity.