INTRODUCTION

Recent changes in the nutritional profile of the population, such as the significant increase in overweight and obesity prevalence, are a reflection of the nutritional transition occurring over the past decades (1). Obesity is a chronic non-communicable disease (NCD) defined as abnormal fat accumulation. It is diagnosed by measuring body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference, which are important predictors of cardiovascular disease. Obesity has a multifactorial etiology and is associated with genetic, environmental, and behavioral factors, hindering management and control (2).

Of the environmental factors influencing obesity, emotional aspects and stress are those most closely related to weight gain. Stress leads to increased levels of glucocorticoids, which can contribute to the increase in visceral fat and subsequent development of metabolic syndrome components (3). A vicious cycle is formed: stress enhances glucocorticoid action, leading to weight gain, which, in turn, contributes to stress. Cortisol levels are also increased in obese patients, being related to increased caloric intake (4). Obese individuals are psychologically affected by social prejudices and stigma, factors associated with morbidity and mortality, regardless of weight or BMI (5). Some obese individuals may adopt calorie-restricted or other types of restricted diets (6), predisposing to binge eating (7).

The binge-eating disorder (BED) is formally recognized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - Fifth Edition (DSM-5) (7). Binge eating is characterized by recurrent consumption of food in large quantities, accompanied by a feeling of loss of control and anguish. There are no compensatory behaviors after binge eating episodes (e.g., induced vomiting, use of laxatives, or physical exercise), and it is detached from the goal of weight control (7,8). BED is frequently observed in overweight and obese individuals who seek medical treatment, with a prevalence of more than 20 % in this population (1). The term adherence is defined as the extent to which patients consent to the treatment recommended by health professionals and is an important component for successful weight loss (9). Binge eating is positively associated with low adherence to dietary treatment in obese individuals and NCD patients, the opposite of instituting a diet based on food preferences. There are several factors that hinder adherence to dietary treatment by this group. Considering that the adoption of a healthy lifestyle directly influences weight (10) and that obesity has a negative impact on life expectancy, it is of paramount importance to identify barriers to treatment success. Thus, this study aimed to evaluate whether BED may be an obstacle to diet adherence in obese patients referred for dietary treatment.

METHODS

This is a cohort study conducted at a nutrition and metabolic disease outpatient unit of a general hospital in Porto Alegre, in the south of Brazil, between September 2018 and November 2019. The sample comprised 73 obese individuals (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) (11) of both sexes aged 18 years and over who agreed to participate in the study and signed an informed consent form. Patients without cognitive capacity to answer the questionnaires and those unable to perform anthropometric measurements, such as amputees, wheelchair users, and morbidly obese individuals, were excluded from the study.

Data collection was performed on two occasions, at baseline and follow-up. At first contact, participants were assessed by the nutrition team during a standard clinical visit and received an individualized eating plan and nutritional recommendations for the treatment of obesity (12). The second data collection took place three months later.

Anthropometric measurements, sociodemographic and clinical variables, eating habits, and physical activity level were analyzed. In the anthropometric assessment, participants were evaluated for body weight (kg), height (cm), waist circumference (cm), and neck circumference (cm). Body weight and height data were used to calculate BMI values. Body weight and height were measured using a calibrated anthropometric scale coupled to a stadiometer. Waist and neck circumferences were recorded to the nearest centimeter using a 150 cm inelastic tape. Waist circumference was measured at the midpoint between the last rib and the iliac crest, and neck circumference at the midpoint of the neck (13).

Physical activity was assessed using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ). Participants were categorized as sedentary, active, or very active (14).

Eating habits were recorded on a three-day food diary comprising two weekdays and one weekend day. Food intake data were then analyzed using DietWin® software (Porto Alegre, Brazil). The total energy intake (kcal) was calculated, and macronutrient (carbohydrate, protein, and total fat) and saturated fat intakes were quantified as percentage contributions to the total energy value. When present in food recalls, the energy delivered by alcohol was considered. Fiber intake was calculated in grams and cholesterol intake in milligrams. The amount of oil used during at-home meal preparation was not recorded on food diaries. Instead, we adopted a fixed amount of vegetable oil consumed per person per day. This decision was made taking into account data from the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics based on the Brazilian Household Budget Survey showing that the foods with the lowest variation in consumption are vegetable oil and fats, which account for 12.7 % of the total energy intake in Brazil (15). The total quantity of nutrients consumed during the three-day record period was calculated and divided by three to obtain mean values. Differences between recommended and actual energy and nutrient intakes were used to assess adherence to dietary treatment. The calorie/day recommendation was around 1,000 to 1,500 kcal/day for women and 1,200-1,800 kcal/day for men. The distribution of nutrients was as follows: 20 % to 30 % of fats, 55 % to 60 % of carbohydrates and 15 % to 20 % of proteins (2).

BED was identified using the Binge-Eating Scale (BES). On the basis of BES scores, participants were divided into two groups, BED (BES score ≥ 17) and non-BED controls (BES score < 17) (16).

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Santa Casa de Misericórdia, Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil (protocol no. 2,538,206). The study posed minimal risk to patients, and all procedures were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and national and international guidelines for research involving human beings.

SAMPLE SIZE CALCULATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Sample size was calculated using WinPEPI for Windows version 11.43, according to Masheb et al. (17) and Yanovski et al. (18). Assuming a level of significance of 5 %, power of 80 %, weight loss of 1.5 kg in the BED group and 3 kg in the control, and effect size of 0.7 standard deviations between groups, we found a minimum sample size of 68 patients.

Quantitative variables are reported as mean and standard deviation. Categorical variables are presented in absolute and relative frequencies. Differences in categorical variables between groups were analyzed using Pearson's Chi-squared or Fisher's exact tests, and differences in age were assessed using Student's t-test. Generalized estimating equation models with Bonferroni correction were used to examine changes in quantitative parameters over time according to BED presence or absence. These results are presented as mean and 95 % confidence intervals. McNemar's test was used to assess changes in physical activity within groups. Treatment adherence within groups was analyzed using one-sample Student's t-tests (difference = 0), whereas independent Student's t-tests were used to compare differences from the recommended values between groups. The level of significance adopted for all analyses was 5 % (p < 0.05). Data were entered in an Excel spreadsheet, and analyses were performed using SPSS software version 25.0.

RESULTS

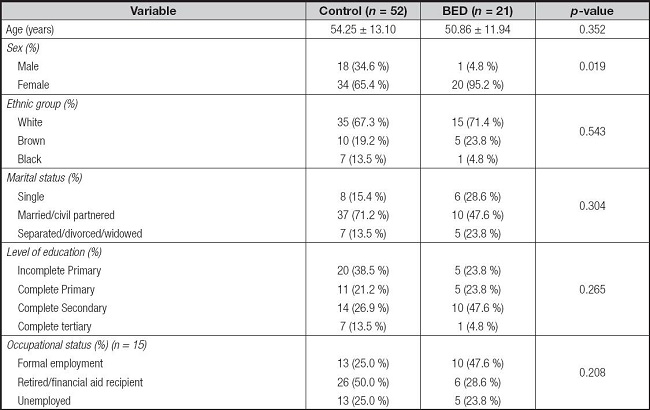

A total of 73 patients participated in the study, 28.7 % of which had BED. The mean age was 52.5 ± 12.5 years, 74 % (n = 54) were women, 81 % (n = 56) were from the Porto Alegre metropolitan area, 68.5 % (n = 50) were white, and 64 % (n = 47) were married or partnered. Regarding level of schooling and source of income, 34 % (n = 25) had incomplete primary education and 44 % (n = 32) received retirement or disability income. Table I describes the sociodemographic profile of BED and control patients. It was observed that 37 % (n = 20) of women had the disorder. Of all individuals with BED, 95 % were women (p = 0.019).

Table I. Sociodemographic characteristics of study participants according to the presence of binge-eating disorder (BED). Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, 2019.

Quantitative data are presented as mean and standard deviation and qualitative data as absolute and relative frequencies. Differences between groups were assessed by Student's t-test for quantitative data and by the Chi-squared test for qualitative data, both at p < 0.05.

No significant differences in comorbidity prevalence were observed between groups. We assessed the presence of type 1 diabetes mellitus (p = 0.318), type 2 diabetes mellitus (p = 1.000), systemic arterial hypertension (p = 0.153), dyslipidemia (p = 0.404), increased triglycerides (p = 0.142), cardiovascular diseases (p = 0.494), and other endocrine diseases (p = 0.713).

Of patients without BED, 30.8 % reported having a restrictive diet without professional advice and 48.1 % reported having consulted with nutritionists. About that, in the BED group, 69.2 % reported having a restrictive diet without professional advice and 51.9 % reported having consulted with nutritionists. Adoption of restrictive diets was significant in the BED group (p = 0.028).

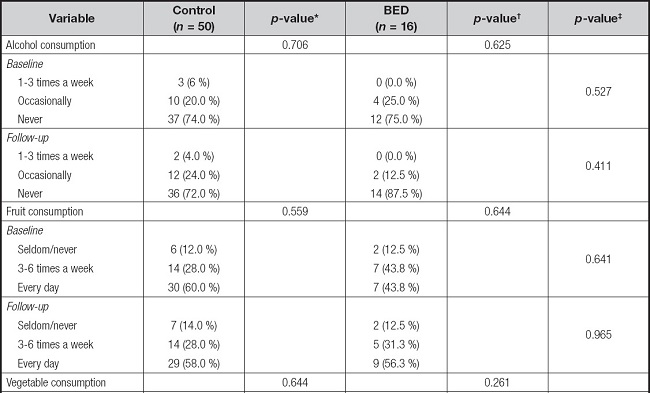

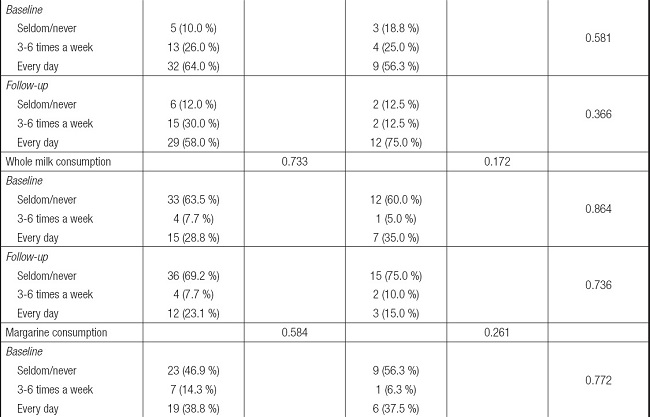

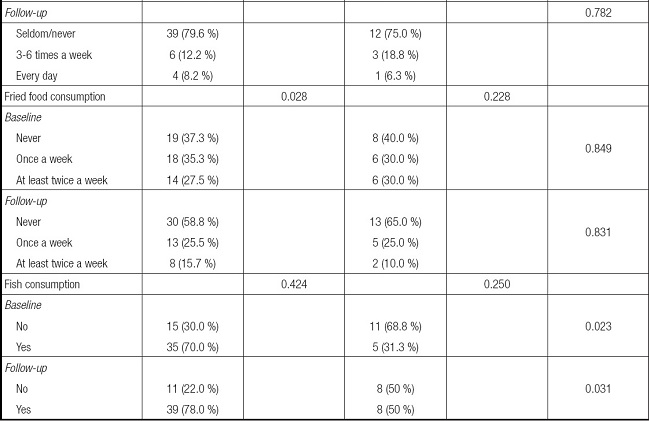

Table II describes the dietary habits of obese individuals with and without BED at baseline and follow-up. There were significant differences in fatty meat (p = 0.035) and chicken skin (p = 0.006) consumption between groups, with higher levels in the BED group. Fish consumption was also more frequent among BED individuals. This behavior was observed both at baseline and follow-up. Fried food consumption decreased significantly in the BED group at follow-up. Most participants (60.3 %) reported never having smoked (p = 0.485). No differences in changes in physical activity were observed between groups (p = 0.951).

Table II. Alcohol consumption and dietary habits of obese individuals at baseline and 3-month follow-up, stratified by presence of binge-eating disorder (BED). Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, 2019.

Table II (Cont.). Alcohol consumption and dietary habits of obese individuals at baseline and 3-month follow-up, stratified by presence of binge-eating disorder (BED). Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, 2019.

Table II (Cont.). Alcohol consumption and dietary habits of obese individuals at baseline and 3-month follow-up, stratified by presence of binge-eating disorder (BED). Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, 2019.

Qualitative data are presented as absolute and relative frequencies. Baseline and follow-up results were compared by McNemar's test. Differences between BED and control individuals were assessed by the Chi-squared test. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

*Comparison between baseline and follow-up results of the control group.

†Comparison between baseline and follow-up results of the BED group.

‡Comparison between BED and control groups.

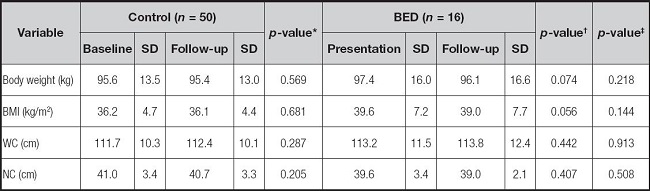

Table III shows the anthropometric measurements of BED and control groups at baseline and follow-up. Body weight, BMI, and waist circumference were numerically higher in the BED group at both times. Anthropometric measurements were numerically lower at follow-up, but differences were not significant.

Table III. Anthropometric measurements of obese individuals at baseline and 3-month follow-up, stratified by presence of binge-eating disorder (BED). Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, 2019.

BMI: body mass index; WC: waist circumference; NC: neck circumference. Values are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD). Differences between baseline and follow-up results were analyzed using generalized estimating equation models with Bonferroni correction.

*Comparison between baseline and follow-up results of the control group.

†Comparison between baseline and follow-up results of the BED group.

‡Comparison between BED and control groups.

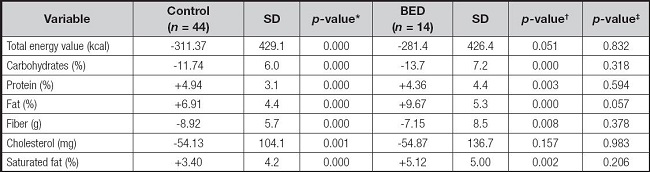

Table IV shows the differences between nutritional recommendations and effective consumption, as estimated by food records. Adherence was measured by differences between recommended and actual intakes and compared between groups. In the control group, there was a lower intake of total energy, carbohydrates, fiber, and cholesterol but a higher intake of protein, total fat, and saturated fat at follow-up. In the BED group, similar reductions were observed at follow-up, except for total energy and cholesterol intake.

Table IV. Differences between recommended and actual intake of macronutrients, fibers, cholesterol, and saturated fat in obese individuals, stratified by presence of binge-eating disorder (BED). Porto Alegre, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, 2019.

Adherence to dietary treatment was assessed within and between groups by one-sample and independent Student's t-tests, respectively.

*Comparison between baseline and follow-up results of the control group.

†Comparison between baseline and follow-up results of the BED group.

‡Comparison between BED and control groups.

DISCUSSION

We observed no differences in adherence to dietary treatment, energy intake, or changes in anthropometric measurements between obese patients with and without BED. The prevalence of BED observed here was similar to that reported in previous studies (1,19), in which 24-30 % of overweight/obese patients seeking treatment for weight loss had BED. Kessler et al. (26) observed an even higher prevalence among grade I obese individuals. Most participants of the current study (BED and control groups) were classified as having grade II obesity, and our results differed from those of the previously mentioned study (20). Because BED and obesity are public health problems, it is suggested to include questions related to eating problems in medical records to increase the access of individuals with BED to adequate treatment (20-22).

The odds ratio of BED in women is up to three times greater than that in men (23), in agreement with our results. These findings can be attributed to the fact that men are less likely to seek health care (24) because of individual and social issues (25).

Given that this study took place in a nutrition outpatient unit, the vast majority of participants had at least one comorbidity associated with obesity. Therefore, it was not possible to identify significant differences in the presence of metabolic syndrome components between BED and non-BED individuals. Such results indicate that obesity alone greatly affects quality of life, being a risk factor for metabolic comorbidities, regardless of binge eating (19). Leone et al. (26) argued that the development of metabolic syndrome and its components in patients with BED is due to obesity and inadequate lifestyle.

Effective total energy intake was lower than the recommended in both groups, although a significant difference was only observed in the control group, attributed to the adoption of restricted diets. Overall, two- and one-third of individuals with and without BED, respectively, reported having adopted calorie-restricted diets in the past. There were no significant differences in calorie restriction between groups, as also observed in a study by Ricca (19). Biagio et al. found that 71 % of a group of obese individuals had already performed this restriction prior to outpatient care (27). We must take into account the possibility of underreporting of food intake, a behavior that is closely associated with obesity and dietary restriction. Underreporting energy intake may lead to the underreporting of macronutrient intake, as previously observed for carbohydrate consumption (28).

In line with the results of the current study, Raymond et al. (29) did not observe differences in total energy intake between obese women with and without BED. The authors also found an increase in fat intake on days when binge eating episodes occurred. Although we did not evaluate the occurrence of binge episodes in BED individuals, we found that this group had higher fat intake. Another study observed an increase in the consumption of this macronutrient with emotional eating (27).

Few studies have investigated the relationship between eating habits and BED. Wilson et al. (30) observed that women with BED have a higher BMI and tend to consume more fat and fewer fruits and vegetables. In the present study, although the BED group had a numerically higher fat intake, no significant differences were observed in the consumption of fatty foods between groups at either time of data collection. Similarly, fruit and vegetable consumption did not differ between groups. Therefore, it was not possible to identify a specific relationship between food intake and the presence of BED.

Eating disorders are positively correlated with other psychiatric disorders, such as alcohol use. BED may increase the possibility of alcohol consumption by 2.2 % (21). It is suggested that the same mechanism that predisposes to high food consumption, driven by compulsion, relief, compensation, and emotional numbness, may promote excessive alcohol consumption (31). However, no significant difference in alcohol consumption was observed between groups. This may be due to the fact that the analyzed patients are part of a multidisciplinary support network that constantly recommends reducing alcohol consumption, given that weight is a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases (32).

Considering that the presence of BED did not significantly affect adherence to dietary treatment and that, even with the lower-than-targeted intake of energy and carbohydrates, there were no major changes in anthropometric patterns, it is unclear why this group of patients did not adhere to the diet, as evidenced by the low intake of fiber and high intake of total and saturated fats, and what can be done to change this outcome.

Eating behavior is influenced by various aspects, and there is a fusion of social, cognitive, and emotional factors. Low food quality, urbanization, greater inclusion of women in the labor market, economy, and globalization are some of the factors that favor obesity development (33). Chea and Mobley (34) highlighted the impact of low income on dietary patterns; low-income individuals were shown to have difficulty in correctly identifying whole foods, which interferes with their food choices. However, little has been said about other eating behavior determinants, such as motivation, whether internal or external. It is necessary to recognize the need to change eating habits to improve one's health, and, often, only internal motivation makes this possible (8,35).

The transtheoretical model of behavior change may assist health professionals in providing nutritional guidance and identifying the patient's stage of change at presentation (36). The model contributes to nutritional education planning, leading individuals to lasting improvements (7). Its use has led to a decrease in high-sugar and high-fat food consumption, weight loss, and improved body perception (37).

The motivational interview is a method focused on the patient and aimed to expand internal motivation for change. The patient does not just follow guidelines, but walks with the health professional towards change. Health professionals, together with patients, need to define goals and devise strategies. The professional must listen, be understanding, and not act prescriptively. In this case, low adherence is not seen as a result of the individual's reluctance but as a behavior to be improved (38). Selçuk-Tosun et al. (39), in a randomized clinical study, observed that individuals participating in a motivational interview intervention had better outcomes in relation to self-efficacy and metabolic control. The intervention also increased the number of individuals at the maintenance stage of change toward healthy eating.

Thus, identifying the stage of change at which patients find themselves and defining the best intervention method for each case by taking into account the whole context could promote patient adherence to dietary treatment, given that interventions that only focus on nutritional changes have proven ineffective (19). Another suggestion is to promote collective treatment and group meetings, strategies that were found to improve adherence in the study of Inelmen et al. (40).

STRENGTH AND LIMITS

The strength of our work is in the emphasis that obesity is a multifactorial disease and must be treated in this way. For the nutritional recommendation to be successful, we must use other approaches that are decisive in eating behavior. A limitation of this study was the small sample size. Furthermore, food records are subject to underestimation of portion size, a pattern known as the flat-slope syndrome, associated with difficulties in correctly estimating food portions.

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT?

It was known that binge eating favors low adherence to nutritional guidelines. Considering obesity as a worldwide epidemic, we would like to know if BED itself was an obstacle to diet adherence within this group.

WHAT YOUR STUDY ADDS?

As a result of this study, we observed that, although BED is, in isolation, a barrier to nutritional adherence, obesity itself also contributes negatively to adherence to dietary treatment, requiring more than a prescriptive treatment in the treatment of obese individuals. We suggest that health professionals working in the obesity scenario apply tools such as the Transtheoretical Model of Behavior Change and the motivational interview, in order to positively assist in the adherence to nutritional interventions.

CONCLUSION

It was not possible to observe a relationship between BED and adherence to dietary treatment. Obese individuals with BED did not have a higher presence of metabolic comorbidities or specific eating patterns compared with obese individuals without BED. Thus, we found that obesity is a contributing factor to the difficulty of adhering to dietary recommendations. More studies are needed to confirm the importance of applying cognitive methods to this patient group to improve the effectiveness of dietary treatment.