Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Anales de Psicología

versión On-line ISSN 1695-2294versión impresa ISSN 0212-9728

Anal. Psicol. vol.32 no.2 Murcia may. 2016

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.32.2.197991

Action-Emotion Style, Learning Approach and Coping Strategies, in Undergraduate University Students

Estilo de Acción-Emoción, enfoque de aprendizaje y estrategias de afrontamiento en estudiante universitarios no graduados

Jesús de la Fuente1, José Manuel Martínez-Vicente1, José Luis Salmerón2, Manuel M. Vera3 and María Cardelle-Elawar4

1 University of Almería (Spain).

2 Psychologist (Spain).

3 University of Granada (Spain)

4 Arizona State University (USA).

This research was carried out within the framework of R & D Project ref. EDU2011-24805 (2012-2015), MICINN and FEDER Funds.

ABSTRAC

Action-Emotion Style (AES) is an affective-motivational construct that describes the achievement motivation that is characteristic of students in their interaction with stressful situations. Using elements from the Type-A Behavior Pattern (TABP), characteristics of competitiveness and overwork occur in different combinations with emotions of impatience and hostility, leading to a classification containing five categories of action-emotion style (Type B, Impatient-hostile type, Medium type, Competitive-Overworking type and Type A). The objective of the present research is to establish how characteristics of action-emotion style relate to learning approach (deep and surface approaches) and to coping strategies (emotion-focused and problem-focused). The sample was composed of 225 students from the Psychology degree program. Pearson correlation analyses, ANOVAs and MANOVAs were used. Results showed that competitiveness-overwork characteristics have a significant positive association with the deep approach and with problem-focused strategies, while impatience-hostility is thus related to surface approach and emotion-focused strategies. The level of action-emotion style had a significant main effect. The results verified our hypotheses with reference to the relationships between action-emotion style, learning approaches and coping strategies.

Key words: Type-a behavior pattern; learning approach; coping strategies; stress; ex post facto study.

RESUMEN

El Estilo Acción-Emoción (EAE) es un constructo psicológico de tipo motivacional-afectivo referido a la motivación de logro, basado en el Patrón de Conducta tipo A (pCTA), característico de los alumnos, en interacción con situaciones de estrés. La combinación de la competitividad y la sobrecarga laboral, con las emociones de la impaciencia y hostilidad, conduce a una clasificación en cinco categorías de estilo de acción-emoción (Tipo B, tipo Impaciente-hostil, Tipo Medio, Tipo Competitivo-Sobrecarga Laboral y Tipo A). El objetivo de la presente investigación fue establecer la relación entre las características del EAE con los enfoques de aprendizaje (enfoque profundo y enfoque superficial) y las estrategias de afrontamiento (centradas en la emoción y centradas en el problema). La muestra estuvo compuesta por 225 estudiantes del Programa de Licenciatura en Psicología. Se realizaron análisis de correlaciones bivariados de Pearson y análisis multivariados. Los resultados mostraron una asociación positiva y significativa de las características de la competitividad-sobrecarga con el enfoque profundo y las estrategias centradas en el problema, así como de la impaciencia-hostilidad con el enfoque superficial y las estrategias centradas en la emoción. El nivel de estilo de acción-emoción tuvo un efecto principal significativo. Los resultados obtenidos verifican las hipótesis planteadas referidas a la relación entre el estilo de acción-emoción, los enfoques de aprendizaje y las estrategias de afrontamiento.

Palabras clave: Estilo de acción-emoción; patrón de conducta tipo-A; enfoques de aprendizaje; estrategias de afrontamiento; estrés académico.

Introduction

The study of stress in the academic environment is an important research focus for defining personal and contextual factors that influence the individual's response. One highly current topic in this line of research is the impact of emotional processes on the student's academic process (Minarro, Gilar y Castejon, 2014). Pekrun and Stephens (2012) affirm that academic emotions have not been adequately addressed in Educational Psychology, in contrast to the attention they have received in other scientific disciplines such as neuroscience and the humanities. However, they are critically important, because they affect the other learning processes, whether cognitive (attention and use of strategies) or motivational (goals and self-regulation). The experience of positive emotions can help students to set goals, solve problems creatively and use self-regulation, while negative emotions may interfere with academic achievement, test performance, and even affect one's health (Zeinder & Matthews, 2011). For all these reasons, emotions are very important for students and for teachers (Schutz & Pekrun, 2007).

The teaching-learning context at university can involve a number of stressful situations, since students may not fully master the new environment. This leads to stress responses, and in the worst cases to academic failure (Álvarez, Aguilar & Lorenzo, 2012; González, 2006). Research in this area has revealed high rates of stress in university student populations, especially in the first years of their degree, and just before testing periods. The most notable academic stressors are excessive homework, final exams, and final exam preparation (Martín, 2007). Exams and assessment situations have important consequences for students in that they can actually determine the course of the student's academic and vocational career. Being able to effectively cope with these situations, both cognitively and emotionally, is therefore important to the student's psychological well-being and to achievement of their goals (Zeidner, 1995).

Action-Emotion Style as a motivational-affective, presage variable of academic stress

The construct Action-Emotion Style, AES (de la Fuente, 2008; de la Fuente, 2011, de la Fuente et al, 2013) is a variable based on the psychological construct referred to as Type-A Behavior Pattern, TABP (de la Fuente & de la Fuente, 1995, 1998; Friedman, & Rosenman, 1974; Matthews, 1982; Moyano et al., 2011). However, there are certain differences. The TABP emerged within the healthcare context, in order to explain certain characteristics, or a certain behavioral pattern in response to stress, found in subjects with high coronary risk, attempting to establish which elements of this behavior are harmful or protective (Chida, & Steptoe, 2009; Kardum, & JHudek-Knezevic, 2012; Robinson, & Wilkowski, 2010; Steptoe, et al., 2010). Action-emotion style, however, has emerged in the educational context, to explain differences in students' achievement motivation. It assumes that the components involved are found in different combinations within the population, and can explain academic performance. In fact, a clear relationship has already been demonstrated between characteristic behaviors of the competitive-hardworking component, and academic performance in university students (de la Fuente & Cardelle-Elawar, 2009).

De la Fuente (2008) described Action-Emotion Style as an interactive personal variable of achievement motivation, resulting from the combined interrelation of the different components of the Type-A behaviour pattern, when interacting with the academic learning process at university. Not all components that form part of the construct were found to have the same effect on learning. This fact left open the possibility of establishing different student profiles with different combinations of elements, based on relatively stable behaviours and emotions -or achievement motivation styles -which students manifest to a greater or lesser degree when performing learning activities. Prior studies clearly established different student groups in terms of their achievement motivation style with type-A or type-B constructs (Berrios-Martos & García-Martínez, 2006; Moyano et al., 2011) or they studied the components in achievement motivation (Sanchez-Elvira, Bermudez, & Perez-Garcia, 1990). However, if we combine the motivational-affective characteristics of competitiveness and overwork, with emotions of impatience and hostility, the result is a classification with five categories of action-emotion style:

Type 1. Type-B Action-Emotion Style (TB). This type of subject has been studied often in classic research, being the conceptual opposite of Type-A. These students are characterized by an absence or low level of the characteristic emotional dimensions that define the TABP: low in competitiveness-overwork and impatience-hostility.

Type 2. Impatient-Hostile Action-Emotion Style (IH). This category includes students characterized by the following behaviors: low in competitiveness-overwork and high in impatience-hostility dimensions of the TABP.

Type 3. Medium Action-Emotion Style (M). As the name indicates, this category includes those students who have medium scores on all the behavioral strategies, both in terms of motivational and affective-emotional strategies, and also attitudinal strategies. The bulk of the population falls into this category. This type, medium in competitiveness-overwork and impatience-hostility dimensions of TABP, has received little attention in the classic studies on the TABP construct.

Type 4. Competitive-Overworking Style (CO). This behaviour characteristic has been studied in research on the TABP components, but the studies to date are much fewer than in the case of Type A or Type B styles. This category would include those students with the following behavioural characteristics: high in competitiveness-overwork and low in impatience-hostility dimensions of TABP.

Type 5. Type-A Action-Emotion Style (TA). This category includes students who are noted for a high presence of all the above components (competitiveness, overwork, impatience-hostility and a fast-paced life), thus configuring a complex personal style that results from several tendencies: high in competitiveness-overwork and impatience-hostility dimensions of TABP.

Differential relationships are sufficiently well-established between extreme groups of this behavior pattern (Type A and Type B) in their relation to stress (Lala, Bobirnac & Tipa, 2010) and emotionality (Lee, & Watanuki, 2007). There is also evidence that learning approaches are related to selfregulation (Beishuizen, Stoutjesdijk & Van Putten, 1994; Heikkiläa, & Lonka, 2006; Lonka & Lindblom-Ylanne, 1996), to anxiety, and resilience (de la Fuente et al., 2012). While possible relationships of action-emotion style to learning approaches and to coping strategies have yet to be explored, such relationships are plausible.

Learning approach as a motivational-affective variable in the learning process

Biggs (1988) defined learning approaches as learning processes that emerge from students' perceptions of the academic tasks, influenced by their own personal characteristics. Learning approaches are characterized by the influence of the metacognitive process as a mediating element between the student's intention or motive and the learning strategy used for studying. He indicates that two different levels of study are addressed by learning approaches (Biggs, 1993): one is more specific, directed toward a concrete task (approach as a process) and the other, more general (approach as a predisposition). Some studies have demonstrated that both surface approach and deep approach are determined by university students' perception of the learning context and by their motivation (Biggs, 2001; Watkins, 2004).

Coping strategies as stress-regulating variables

Lazarus and Folkman (1984) defined coping as the subject's constantly changing cognitive and behavioural efforts to manage specific external and/or internal demands that are considered to consume or exceed the person's resources. According to their classic model of transactional coping, discomfort is produced when persons perceive that the environmental demands exceed their capacities and available resources; hence, their appraisal of the stressor is what determines the level of stress that is experienced. Consequently, psychological well-being and health are more influenced by one's manner of coping than by the mere presence of difficult situations (Lazarus, 1983). Psychological stress "is a particular relationship between the person and the environment that is appraised by the person as taxing or exceeding his or her resources and endangering his or her wellbeing (1984, p. 19)". These authors conceive stress as resulting from a transaction between the individual and the environment, such that coping would be determined by the person, the environment, and the interaction between the two.

Folkman and Lazarus (1984) proposed two styles of coping, each with its corresponding strategies: coping that focuses on the problem -modifying the problem situation to make it less stressful-and coping focused on the emotion -reducing the tension, physiological activation and emotional reaction (Folkman, Lazarus, Dunkel-Shetter, DeLongis & Gruen, 1986). Both forms of coping are used in most stressful encounters, in proportions that depend on one's appraisal of the situation. For example, in Folkman and Lazarus's analysis of 1300 stressful episodes, people tended to use more problem-focused strategies in a situation appraised as changeable, and more emotion-focused strategies when the situation was appraised as not changeable, or less so (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980).

According to Lazarus and Folkman (1984), at least two types of factors directly influence how people appraise and cope with situations: individual characteristics and the characteristics of the situation. In the first group, for example, there are commitments (defining what is important and what is at stake for the individual), beliefs, and personal traits such as self-esteem (Rector & Roger, 1997). In the group of situational factors, there is the novelty or predictability of the situation, its uncertainty, timing issues (i.e., time generally intensifies the threat, but can also be an opportunity to think things through) or situational ambiguity (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). There is much recent evidence on the different adaptive value of the two strategy types (An, Chung & Park, 2012; Nielsen & Knardahl, 2014).

Aim and hypotheses

Based on this possible relationship, the general objective of this investigation was to determine how the construct actionemotion style may be bivariate associated and interdependent with learning approach and coping strategies. Based on previous evidence, it was hypothesized that:

1. The competitiveness-overwork dimension of the construct will show a positive association with deep approach and with problem-focused coping strategies. By contrast, the impatience-hostility dimension will show a positive association with surface approach variables and with emotion-focused strategies.

2. The five levels of the construct Action-Emotion Style (AES) will significantly determine the levels of these motivational-affective variables (learning approach and coping strategies). Specifically, Type 4 (competitive-overworking style) is expected to show higher scores in deep approach and problem-focused coping than will Type 2 (impatient-hostile). In contrast, the impatient-hostile type will show high scores in surface approach and emotion-focused coping strategies. Specifically, the impatient-hostile type will show significantly higher levels of emotion-focused coping strategies that have to do with emotional venting and avoidance.

Method

Participants

The sample was composed of 225 students (165 female and 60 male) in the 4th year of the Psychology Degree program at universities in the south of Spain, with a mean age of 21.06 years (SD= 3.10). Preliminary analyses showed an absence of significant main effects of the gender variable on the other variables studied.

Instruments

Action-emotion style. The Jenkins Activity Survey for students Form H (JASE-H) was used. This scale, used for measuring the TABP, has been adapted (Bermudez, Perez-Garcia & Sanchez-Elvira, 1990; Bermudez, Sanchez-Elvira & Perez-Garcia, 1991) from the Jenkins Activity Survey in its T version (Krantz, Glass & Snyder, 1974). It contains 4 factors: Impatience, Hostility, Competitiveness and Overwork. In total, the questionnaire contains 32 items, each with a six-point Likert-type response format, where the subject must choose the degree to which the item applies to him or her. A value of one means that it is not at all applicable to the subject, and six means it is totally applicable. The JASE-H offers both a global TABP score, obtained by adding the scores from all of the items, and specific measurements for each of the components that comprise the TABP. The JASE-H presents high internal consistency (alpha coefficient of 0.85 for the total scale, 0.81 for the Impatience-Hostility factor, 0.82 for Competitiveness and 0.70 for Overwork) and high stability over time, both for the complete scale (0.68) and for each of the above factors (0.61, 0.76 and 0.70 respectively). Reliability and Validity measures reported by the authors are consistent. The statistics are Alpha= .832, and Guttman Split-Half=.803.

Learning approach. The Revised Two-factor Study Process Questionnaire, R-SPQ-2F (Biggs, Kember, & Lerner, 2001) contains 20 items measuring two dimensions of learning approaches: Deep (e.g., I find that at times studying gives me a feeling of deep personal satisfaction') and Surface (e.g., "My aim is to pass the course while doing as little work as possible"). Students are asked to respond to these items on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 ("rarely true of me") to 5 ("always true of me"). The R-SPQ-2F was translated into Spanish, adapted to take cultural differences into account, then independently translated back and further modified where necessary. Justicia et al. (2008) showed a confirmatory factorial structure with a Spanish sample that was similar to the study by Biggs, Kember, & Lerner, (2001), with a first order factor structure of two factors. Both studies reported acceptable reliability coefficients. In the present study Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficients were acceptable (Deep α = .81; Surface α = .77).

Coping strategies. The Escala Estrategias de Coping, EEC [Coping strategies scale] (Sandín & Chorot, 1987) was used in its original version. This scale, based on the Lazarus and Folkman (1984) model, is adapted for university students and contains a total of 90 items. The Escala de Estrategias de Coping (EEC) was developed as a psychometric test that would assess a broad spectrum of ways to cope with stress. This scale was selected because of the wide range of coping behaviors that it assesses in university students. Prior to the present study, a validation study was carried out using this scale with a total of 429 subjects. For internal validity criteria, results from an exploratory factor analysis of main components showed that the questionnaire has a two-factor, second-level structure (forced) that explained 79.36% of the variance: emotion-focused coping strategies (38.58%) and problem-focused coping strategies (31.78%). Reliability of 0.93 was obtained for the complete scale, 0.93 was obtained for the first half, and 0.90 for the second half (Cronbach alpha). The Spearman-Brown and Guttman values were 0.84 and 0.80 respectively, for each dimension. In all cases, the factors of each dimension and their reliability exceed .80.

Procedure

All participants received the necessary information about the research and about how to complete the different questionnaires. Completion of questionnaires was voluntary, during class hours, and took place in the months of February to May, one scale per month, during academic year 2012-2013.

Data analysis

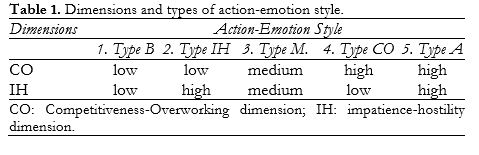

A cross-sectional, retrospective design was used, with attributional (or selection) variables, for predictive purposes (Ato, Lopez, & Benavente, 2013). Pearson bi-variate correlations (two-tailed) were carried out, as well as uni-variate analyses (ANOVAs) and multi-variate analyses (MANO-VAs). Cluster analysis was used to determine the type of AES, with three levels (low-medium-high) for each dimension being established (see Table 1).

Thus, the five groups were established as combinations of low and high levels. For example, Type 2 (impatient-hostile) is the combination of a high level of impatience-hostility and a low level of competitiveness-overwork. The remaining students that did not fit into the classification were discarded; a total of 69 students were dropped from the initial sample. This shows that a large number of subjects cannot be categorized within the proposed model. Students were assigned to the groups as follows: (1) Type-B students had low scores in competitiveness-overwork (between 1 and 3.12) and low scores in impatience-hostility (between 1 and 2.59), (2) Impatient-hostile students had low scores in competitiveness-overwork (between 1 and 3.12) and high scores in impatience-hostility (between 3.50 and 6.00), (3) Medium Type students showed medium scores on competitiveness-overwork (between 3.13 and 3.70) and medium scores on impatience-hostility (between 2.60 and 3.49), (4) Competitive-hardworking students had high scores in competitiveness-overwork (between 3.71 and 6.00) and low scores in impatience-hostility (between 1.00 and 2.59), and (5) Type-A students had high scores in competitiveness-overwork (between 3.71 and 6.00) and high scores in impatience-hostility (between 3.50 and 6.00).

At a second point in time, the correct distribution of each dimension into each group was verified through a MANOVA, using action-emotion style as independent variable, and the two dimensions of the construct as dependent variables. The result was a significant main effect [F (8,546) =140,149,p<.001, eta2 total= .673], and specific effects for the competitive-overworking dimension [F (4,273)=154,707, p<.001, eta2 partial= .694], and the impatience-hostility dimension [F(4,273)=315.693, p<.001, eta2 partial=.822]. Specifically, for Dimension 1, competitive-overworking, significant post-hoc (Sheffe test) differences appeared between all types (p<.001) except between Types 1 and 2, and between Types 4 and 5. Similarly, in Dimension 2, impatience-hostility, significant differences appeared between all types (p<.001), except between Types 1 and 4. Median values are shown in Table 2.

Results

Action-emotion style and learning approach

We find a significant, positive correlation between some of the dimensions of action-emotion style and learning approach. Specifically, the competitiveness-overwork dimension has the closest correlation to learning approach. See Table 3.

The MANOVA by factors of learning approach (dependent variable) was also significant [(Pillai=.241), F(16,912)=1.730 p<.05, eta2 total=.029], with a significant partial effect of AES (independent variable) on deep motivation, [F(4,228)=2.578 p<.05, eta2 partial=.043], deep strategy [F(4, 228)=3.328, p<.01, eta2 partial=.055 (2 < 4,5, p<.05)] surface motivation [F(4,228)=2.464, p<.05, eta2 partial=.043], and surface strategy [F(4,228)=4.181, p<.001, eta2 partial=.068 (2 > 1,3,5,p<.05; 2 < 4,p<.01)]. The MANOVA by dimensions of learning approach was also significant [(Pillai=.283), F(8,456)=3.001,p<.01, eta2 total=.050, with a significant partial effect of AES on deep approach [F(4,228)=3.508, p<.01, eta2 partial=.050 (2 <, 4 and5, p<.05)] and surface approach [F(4, 228)=3.836,p<.01, eta2 partial=.063 (2 >1, 3,4,5,p<.05)]. Direct values are shown below. See Table 4 and Figure 1.

Action-emotion style and coping strategies

Correlational analyses showed a relationship between total score on action-emotion style (AES) and coping strategies (CS), with a correlation of r=.135 (p<.01). Likewise, association relationships appeared between the competitiveness-overwork dimension and problem-focused strategies (r=.176, p<.001) and between the impatience-hostility dimension and emotion-focused strategies (r=.126, p<.01). Specifically, the competitiveness-overwork dimension correlated with factors belonging to problem-focused coping and some factors of emotion-focused coping, while the impatience-hostility dimension correlated exclusively with factors from emotion-focused coping. See Table 5.

MANOVAs that took action-emotion style (AES) as independent variable, and coping dimensions as dependent variables, showed a significant general main effect [(Pillai=.099), F(8,178)= 2.793, p<.01, eta2total=.139] on emotion-focused strategies, F(4,178)= 3.579, p<.01] and on problem-focused strategies [F(8,178)= 4.457, p<.001]. In this case, the impatient-hostile style appears with significantly fewer problem-focused strategies than Type-A and Medium styles.

A significant general effect also appeared for the coping factors, [(Pillai=.511), F(52,1824)= 2.793, p<.001, eta2 total= .128], with a significant partial effect on most factors (p<.01), except factor 3 and factor 11. In the emotion-focused strategies, impatient-hostile students reported fewer strategies of distraction and of seeking help for action, than did Medium and Type-A subjects. In problem-focused strategies, the impatient-hostile students used significantly fewer strategies of selfinstructions (F5) and of positive reappraisal and firmness (F10). However, the competitive-overworking students made greater use of problem-focused strategies (F5, selfinstructions; F10, positive reappraisal; F13, seeking alternative reinforcement), as well as certain emotion-focused strategies (F6, action directed at the causes and F10, preparing for the worst). The mean direct values and the significant differences in the types of students are shown in Table 6.

Finally, in a MANOVA between AES and the items from the significant factors, AES was seen to have a significant main effect on the latter, [F(32, 344)= 1.588, p<.01, eta2 partial=.129], for item 11 (I take out my bad mood on others), item 73 (I act irritable with people), item 82 (I try to feel better by eating, drinking, or taking some other kind of drug), item 10 (I think things will turn out bad no matter what I do), 40 (I myself seek out the information I need to solve my problems), item 63 (I generally avoid contact with people), item 81 (I become less communicative with others) and item 88 (when I have problems, the way I act changes completely). The effect of AES is especially notable on item 82 [F(4,90)=3.688, p<.008, eta2partial=.141], and on item 88 [F(4,90)=2.579, p<.05, eta2partial=.103]. Specifically, the impatient-hostile style produced significantly higher scores on these items, with respect to Type-B and Type CO (p<.05).

Discussion

Action-emotion Style and Learning Approach

The first research hypothesis was satisfied, being validated by the correlations found. Significant associations between different components of AES and learning approach have been confirmed, offering evidence of different motivational-affective achievement styles associated with different dimensions and factors of learning approach. It should be underscored that the competitiveness-overwork component is most associated with deep approach. In contrast, the impatience-hostility component is associated with surface approach. Once more, this evidence helps to corroborate that the competitive-overworking achievement motivation style is associated with a deep learning approach, and enhances performance (Autor & Autor, 2009). However, the impatient-hostile style is associated with the surface approach. This would suggest that the surface approach to learning (consisting of surface learning motivations and strategies) is also associated with negative emotionality experiences (impatience and hostility), as well as test anxiety. The latter was already demonstrated consistently in prior research on the components of the Type A Behaviour Pattern (de la Fuente & de la Fuente, 1995). This behavioural component would tend toward greater experiences of stress in academic situations.

Referring to the effect of action-emotion style, an interdependence relationship between the two constructs is confirmed. Specifically, as was hypothesized, the competitive-overworking students have higher levels of deep approach (deep strategy, especially), and are lower in surface approach; however, the impatience-hostility students have higher levels of surface approach (surface strategy, especially), and are lower in deep approach. This result is coherent with the idea of competitiveness-overwork behavior as a positive variable with a buffering effect against stress (Bermúdez, Pérez-García & Sánchez-Elvira, 1990; de la Fuente et al, 2012).

Action-Emotion Style and Coping Strategies

As for the second hypothesis, results are consistent in that the competitive-overworking style is associated with problem-focused strategies and with certain emotion-focused strategies, while the impatient-hostile style is associated only with emotion-focused strategies, confirming this hypothesis partially. This result provides evidence of the value of coping strategies for a better understanding of the dimensions of the AES construct. Moreover, it is consistent with other prior evidence that has shown the detriment of focusing exclusively on managing emotions as a way of coping, without using problem-focused strategies (de la Fuente et al, 2012). One noteworthy result relates to the use of religious experience as a form of coping. Some studies have shown the stress buffering effect of religious or spiritual experience in some persons (García-Berbén, Muñoz & Entrena, 2007). Results also lend evidence to the behavioural characteristics of impatience and hostility, since this type of student has an excessively negative emotional experience of stress, leading to the use of venting as a mechanism to relieve stress (Sánchez-Elvira, Bermúdez & Pérez García, 1990).

There is a general effect of action-emotion style on university students' coping strategies, although not all the desired significant differences were found. One of the possible reasons, which may be considered a limitation, is the sample used for the analysis, or the probable latent effect of gender, which was not taken into account in the analyses performed. In any case, a clear trend was seen in the impatient-hostile style in its association with the lowest levels of emotion- and problem-focused strategies, and its association with specific behaviors such as anxiety reduction strategies (through escape behaviors, especially) and emotional venting strategies (substance use and radical changes of behavior), consistent with the concept of this component's greater level of psychological reactance (Wortman, & Brehm, 1975). However, the desired effect of the competitive-overworking style on greater use of problem-focused strategies did not appear. This may be due to the fact that this style uses both types of coping strategies, in combination and selectively, as seen in the correlations, and as Lazarus and Folkman (1984) also established in their model.

Future research should clarify some of these issues, overcoming the limitations of our sample. Furthermore, the relationships and explanatory role of action-emotion style are yet to be determined with regard to other highly current variables that constitute presage variables in the learning process, such as personal self-regulation (de la Fuente & Cardelle-Elawar, 2011). In the specific case of the impatience-hostility dimension, results concur with existing evidence of the toxicity or danger of this behavioral dimension in coping with academic stress (Sánchez-Elvira, Bermúdez & Pérez García, 1990). This would be consistent with the relations found between a lack of personal self-regulation and health-risk behaviors (Miller & Brown, 1991; Neal & Carey, 2005) and the negative relation between using avoidant strategies for coping and healthful behaviors (Suls & Fletcher, 1985). For a complementary perspective, it would be interesting to establish the relationships between academic behavioral confidence as a presage variable, and students' coping strategies or resilience, during situations that expose them to achievement stress at university, using the context of the Self-Regulated Learning model (panadero, & Alonso-Tapia, 2014).

Implications

There are important implications of these results, associated with action-emotion style (AES), for understanding learning difficulties with a motivational-affective source, in the context of achievement motivation. Based on AES types, we can consider that students with an impatient-hostile achievement motivation style have a more surface approach. For this reason, students with an impatient-hostile style should be trained in personal self-regulation in general, and particularly in self-regulated learning strategies.

Despite sample limitations, this investigation has shown that the behavioral dimensions and the construct action-emotion style have value and power to establish associations with other motivational-affective variables, now considered classic, in university learning. Yet to be established are the relationships between this construct and coping styles, as a strategic variable in managing stress (putwain, 2011), as well as how this construct affects perception of teaching-learning processes at university (put-wain & Symes, 2011) and finally, how it mediates in engagement and achievement (Martin, 2008; Martin, & Liem, 2010; Skinner & Pitzer, 2012) or burnout (Caballero, Hederich, & Palacio, 2010; Jang, 2008).

In any case, coping strategies should have their proper place in current psycho-educational models of learning strategies, since we have seen their potential in helping us understand the role of motivational-affective strategies while learning under academic stress (Saklofske, et al., 2012).

References

1. Álvarez, J., Aguilar, J.M., & Lorenzo, J. J. (2012). Test Anxiety: relationships with personal and academic variables. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 10(1), 333-356. [ Links ]

2. An, H., Chung, S., & Park J. (2012). Novelty-seeking and avoidant coping strategies are associated with academic stress in Korean medical students. Psychiatry Research, 200(2-3), 464-468. [ Links ]

3. Ato, M., López, J., & Benavente, A. (2013). Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología (A classification system research designs in psychology). Anales de Psicología, 29(3), 1038-1059. [ Links ]

4. Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

5. Bermúdez, J., Pérez-García, A.M., & Sánchez-Elvira, A. (1990). Type-A Behavior Pattern and Attentional Performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 11, 13-18. [ Links ]

6. Bermúdez, J., Sánchez-Elvira, A., & Pérez-García, A.M. (1991). Medida del patrón de conducta Type-A en muestras españolas: Datos psicométricos del JAS para estudiantes. (Measuring the Type-A behavior pattern in Spanish samples. Psychometric data from the JAS for students.) Boletín de Psicología, 31, 41-77. [ Links ]

7. Berrios-Mastos, M.P., & García-Martínez, J.M. (2006). Efecto de la congruencia entre el patrón de conducta tipo A y el tipo de tarea en el rendimiento y la satisfacción. (The effect of congruence between the Type A behavior pattern and type of task on performance and satisfaction). Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 38 (2), 271-284. [ Links ]

8. Biggs, J. (1988). The role of metacognition in enhancing learning. Australian Journal of Education, 32, 127-138. [ Links ]

9. Biggs, J. (2001). Teaching for Quality Learning at University (3rd ed.) Buckingham: Open University Press. [ Links ]

10. Biggs, J. (1993). From Theory to practice: a cognitive systems approach. Higher Education Research and Development, 12, 73-86. [ Links ]

11. Biggs, J., Kember, D., & Leung, D. (2001). The revised two-factor Study Process Questionnaire: R-SPQ-2F. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 71, 133-149. [ Links ]

12. Caballero, C., Hederich, Ch., & Palacio, J. (2010). El burnout académico: delimitación del síndrome y factores asociados con su aparición. (Academic burnout: defining the syndrome and the factors associated with its appearance). Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 42, 131-146. [ Links ]

13. Chida, Y., & Steptoe, A. (2009). The Association of Anger and Hostility with Future Coronary Heart Disease A Meta-Analytic Review of Prospective Evidence. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 53(11), 936-946. [ Links ]

14. de la Fuente, J. (2008). Action-Emotion Style as Charasterictic of Achievement Motivation in University Students. In A. Valle, J.C. Núñez, R. González-Cabanach, J.A. González-Pienda, & S. Rodríguez (Eds.). Handbook of Instructional Resources and Their Applications in the classroom (pp. 297-310). New York: Nov Science Publishers. [ Links ]

15. de la Fuente, J. (2012). Factores motivacionales en el aprendizaje escolar. (Motivational factors in school learning.) In M.V. Trianes (Comp.), Psicología la Educación y del Desarrollo en contextos escolares (pp. 247-264). Madrid: Pirámide. [ Links ]

16. de la Fuente, J., & Cardelle-Elawar, M.C. (2009). Research on actionemotion style and study habits: Effects of individual differences on learning and academic performance of undergraduate students. Learning & Individual Differences, 19(5), 567-576. [ Links ]

17. de la Fuente, J., & Cardelle-Elawar, M. (2011). Personal Self-Regulation and Coping Style in University Students. In L.B. and R.A. Nichelson (Eds.), Psychology of Individual Differences (pp. 171-182). New York: Nova Science Publisher. [ Links ]

18. de la Fuente, J., Cardelle-Elawar, M., Sander, P. y Putwain, D. (2013). Action-Emotion Style, Test Anxiety and Resilience in Undergraduate Students. In C. Boyle (Ed.), Student Learning: Objectives, Opportunities and Outcomes (pp. 139-149). New York: Nova Science Publisher. [ Links ]

19. de la Fuente, J., & de la Fuente, M. (1995). Análisis componencial del Patrón de Conducta tipo-A y respuestas ansiógenas situacionales específicas. (Component analysis of the Type-A Behavior Pattern and specific situational anxiogenic responses). Psicothema, 7(2), 267-282. [ Links ]

20. de la Fuente, J., Martínez-Vicente, J.M., Zapata, L., Sander, P., Cardelle-Elawar, González-Torres, M.C., & Artuch, R. (2012). Action-emotion style as a presage of motivational-affective difficulties in university contexts with stress. Symposium presented to 21th Congress on Learning Disabilities. Oviedo: September 9-12. [ Links ]

21. Friedman, M., & Rosenman, R.H. (1974). Type A Behavior and your Heart. New York: Knopf. [ Links ]

22. Folkman, S., & Lazarus R. S. (1980). An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21, 219-239. [ Links ]

23. Folkman, S., Lazarus, R., Pimley, S., & Novacek, J. (1987). Age differences in stress and coping processes. Psychology Aging, 2, 171-184. [ Links ]

24. García-Berbén, A.B., Muñoz, & Entrena, J.A. (2007). Autorregulación, inteligencia emocional y espiritualidad. (Self-regulation, emotional intelligence and spirituality). In Proceedings from the 5th International Congress on Education and Society (pp. 1-7). Granada: Universidad de Granada. [ Links ]

25. González, I. (2006). Dimensions of assessing university quality in the European Higher Education Area. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 4(3), 445-468. [ Links ]

26. Heikkiläa, A., & Lonka, K. (2006). Studying in higher education: Students' approaches to learning, self-regulation, and cognitive strategies. Studies in Higher Education, 31, 99-117. doi: 10.1080/03075070500392433. [ Links ]

27. Jang, H. (2008). Supporting students' motivation, engagement, and learning during an uninteresting activity. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100, 798-811. [ Links ]

28. Justicia, F., Pichardo, M. C., Cano, F., Garcia-Berbén, A. B., & de la Fuente, J. (2008). The Revised Two-Factor Study Process Questionaire (R-SPQ-2F): Exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses at item level. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 3, 355-372. [ Links ]

29. Kardum, I., & JHudek-Knezevic, J. (2012). Relationships between five-factor personality traits and specific health-related personality dimensions. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 12(3), 373-387. [ Links ]

30. Krantz, D. S., Glass, D. C., & Snyder, M. L. (1974). Helplessness, stress level and coronary-prone behavior pattern. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 10, 284-300. [ Links ]

31. Lala, A., Bobirnac, G., & Tipa, R. (2010). Stress levels, alexithymia, type A and type C personality patterns in undergraduate students. Journal of Medicine Life, 3(2) 200-205. [ Links ]

32. Lazarus, R. S. (1983). Costs and benefits of denial. In S. Breznitz (Ed.) The denial of stress (pp. 1-30). New York: International Universities Press. [ Links ]

33. Lazarus, R.S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer. [ Links ]

34. Lee, J.M., & Watanuki, S. (2007). Cardiovascular responses of Type A and Type B behavior patterns to visual stimulation during rest, stress and recovery. Journal of Physiology Anthropolical, 26(1), 1-8. [ Links ]

35. Martín, I (2007). Estrés académico en estudiantes universitarios. (Academic stress in university students). Apuntes de Psicología, 25, 87-99. [ Links ]

36. Martin, A. (2008). Enhancing student motivation and engagement: The effects of a multidimensional intervention. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 33, 239-269. [ Links ]

37. Martin, A., & Liem, G. (2010). Academic personal bests (pBs), engagement, and achievement: A cross-lagged panel analysis. Learning and Individual Differences, 20, 265-270. [ Links ]

38. Matthews, K.M. (1982). Psychological perspectives on the Type A behavior pattern. Psychological Bulletin, 91(2), 293-323. [ Links ]

39. Miller, W.R., & Brown, J.M. (1991). Self-regulation as a conceptual basis for the prevention and treatment of addictive behaviours. In N. Heather, W.R. Miller and J. Greely (Eds.), Self-control and the addictive behaviours (pp. 3-79). Sydney: Maxwell Macmillan. [ Links ]

40. Miñano, P., Gilar, R., & Castejón, J. L. (2012). A structural model of cognitive-motivational variables as explanatory factors of academic achievement in Spanish language and mathematics. Anales de Psicología, 28, 45-54. [ Links ]

41. Moyano, E., Icaza, G., Mujica, V., Núñez, L., Leiva, E., & Vásquez, M. (2011). Patrón de comportamiento tipo A, ira y enfermedades cardiovasculares (ECV) en población urbana chilena. (Type A behavior pattern, anger and cardiovascular disease (CVD) in an urban population of Chile.) Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 43(3), 443-453. [ Links ]

42. Moyano, E., Icaza, G., Mujica, V., Núñez, L., Leiva, E., Vásquez, M., & Palomo, I. (2011). Patrón de comportamiento Tipo-A, ira y enfermedades cardiovasculares (ECV) en población urbana chilena (Type A Behavior Pattern, Anger and Cardiovascular Disease (CVD) in an urban population of Chile). Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 43(3), 443-453. [ Links ]

43. Neal, D.J., & Carey, K.B. (2005). A follow-up psychometric analysis of the Self-Regulation Questionnaire. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 19 (4). 414-422. [ Links ]

44. Nielsen, M.B., & Knardahl, S. (2014). Coping strategies: a prospective study of patterns, stability, and relationships with psychological distress. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 55(2),142-150. [ Links ]

45. Panadero E., & Alonso-Tapia, J. (2014). How do students self-regulate? Review of Zimmerman's cyclical model of self-regulated learning. Anales de Psicología, 30, 450-462. [ Links ]

46. Pekrun, R., & Stephens, E. J. (2012). Academic emotions. In K.R. Harris, S. Graham, & T. Urdan (EDs.), APA Educational Psychology Handbook (vol. 2, pp. 3-32). Washington, DC. [ Links ]

47. Putwain, D.W. (2011). Discourses of stress in secondary school students. Qualitative Studies in Education, 24(6), 717-731. Doi: 10.1080/09518398.2010.529840. [ Links ]

48. Putwain, D.W., & Symes, W. (2011) Teachers' use of fear appeals in the Mathematics classroom: worrying or motivating students? British Journal of Educational Psychology 81(3), 456-474. Doi: 10.1348/2044-8279.002005. [ Links ]

49. Rector, N. A., & Roger, D. (1997). The stress buffering effects of self-esteem. Personal and Individual Diferences, 23, 799-808. [ Links ]

50. Robinson, M., & Wilkowski, B. (2010). Personality Processes in Anger and Reactive Aggression: An Introduction. Journal of Personality, 78(1), 1-7. [ Links ]

51. Saklofske, D.H., Austin, E.J., Mastoras, S.H., Beaton, L., & Osborne, S.E. (2012). Relationships of personality, affect, emotional intelligence and coping with student stress and academic success: Different patterns of association for stress and success. Learning and Individual Differences, 22, 251-257. [ Links ]

52. Sánchez-Elvira, A., Bermúdez J., & Pérez-García, A.M. (1990). Patrón de conducta type-A y motivación de logro. Implicación de los componentes en la evaluación del rendimiento. (Type A Behavior Pattern and achievement motivation. Implications of its components in assessing performance). Boletín de Psicología, 27, 7-32. [ Links ]

53. Sandín, B., & Chorot, P. (1987). Escala EEC. (The EEC Scale.) Departamento de Psicología de la Personalidad. Madrid: Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia. [ Links ]

54. Schutz, P.A. & Perkrun, R. (Eds.) (2007). Emotion in education. Burlington, M.A.: Academic Press. [ Links ]

55. Skinner, E., & Pitzer, J. (2012). Developmental dynamics of student engagement, coping, and everyday resilience. In S. Christenson, A. Reschly & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Student Engagement (pp. 21-44). New York: Springer. [ Links ]

56. Steptoe, A., Hamer, M., O'Donnell, K., Venuraju, Sh., Marmot, M., & Lahiri, A. (2010). Socioeconomic Status and Subclinical Coronary Disease in the Whitehall II Epidemiological Study. Plus One, 5(1), 1-6. [ Links ]

57. Suls, J., & Fletcher, B. (1985). The relative efficacy of avoidant and non-avoidant coping strategies: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 4, 249-288. [ Links ]

58. Winne, P.H. (2004). Comments on Motivation in Real-Life, Dynamic and Interactive Learning Environments. European Psychologist, 9(4) 257-263. [ Links ]

59. Wortman, C.B., & Brehm, J.W. (1975). Response to uncontrollable outcomes: An integration of reactance theory and the learned helplessness model. In L. Berkowitz, (ed.). Advances in experimental social psychology (vol. 8, pp. 277-336). New York: Academic Press. [ Links ]

60. Zeidner, M. (1995). Adaptive coping with test situations: A review of the literature. Educational Psychologist, 30, 123-133. [ Links ]

61. Zeidner, M., & Matthews, G. (2011). Anxiety 101. New York, NY: Springer. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Jesús de la Fuente Arias,

Department of Psychology.

University of Almería.

Carretera de Sacramento, s/n.

CP 04120. La Cañada de San Urbano.

Almería (Spain).

E-mail: ifuente@ual.es

Article received: 12-05-2014;

Revised: 24-11-2014;

Accepted: 16-06-2015