Mental health disparities in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people are quite well documented in the literature. Several studies have reported differences between sexual minorities and heterosexual individuals in mental health disorders, substance use problems, and suicidality, among others (Gonzales & Henning-Smith, 2017; King et al., 2008; Marshal et al., 2008, 2011; Meyer & Frost, 2013; Plöderl et al., 2006; Plöderl & Tremblay, 2015; Raifman et al., 2020; Ruiz-Palomino et al., 2020; Spittlehouse et al., 2020).

Overall, studies conducted with sexual minority adolescents also demonstrate these differences. Across sexual minority subgroups, research shows, among other things, elevated levels of depression (Bostwick et al., 2014; Denny et al., 2016; Johnson et al., 2011; Marshal et al., 2013; Pesola et al., 2014; Spittlehouse et al., 2020), anxiety disorders (Bostwick et al., 2014; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2008; Spittlehouse et al., 2020), and alcohol and drug-related problems (Birkett et al., 2009; Pesola et al., 2014). Suicidal behavior in particular has consistently been found to be more prevalent in sexual minority youth in several studies (Bostwick et al., 2014; Denny et al., 2016; Duncan & Hatzenbuehler, 2014; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2014; Meyer et al., 2021; Raifman et al., 2020; Salway et al., 2019).

In the scientific literature, a relatively widely accepted explanation for the high prevalence of mental problems among sexual minority individuals is the underlying excessive exposure to stress due to their minority position (Meyer, 1995, 2003; Meyer & Frost, 2013). In addition, this stress can be influenced by the effect of other variables, such as gender or the specific sexual orientation group (e.g., lesbian/gay vs. bisexual) to which the individual belongs (Grollman, 2014).

The evidence about gender, for instance, shows that sexual minority men report more symptoms of poor mental health than women (Moya & Moya-Garófano, 2020; Semlyen et al., 2016). However, these gender differences have not been observed across all age groups. For depression, for example, different studies have reported larger effects in sexual minority men than women (see Plöderl & Tremblay, 2015 for a review). Nonetheless, some research conducted with adolescents has not shown these gender differences (e.g., Almeida et al., 2009; Pesola et al., 2014). Results are much clearer for suicidal behavior as the majority of studies have detected larger effects in men than in women in both adult (see Plöderl & Tremblay, 2015) and adolescent populations (e.g., Almeida et al., 2009; O'Connor et al., 2014; Saewyc et al., 2007).

Regarding differences between sexual orientation subgroups, prior research reveals that bisexual adolescents generally obtain higher scores on mental health problems than lesbian/gay and heterosexual groups, with the lesbian/gay group usually falling between the other two groups. This is the case, for example, of depression (Denny et al., 2016; Marshal et al., 2013) and suicidal behavior (Denny et al., 2016; Hatzenbuehler, 2011; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2014). However, most of the studies have compared combined lesbian/gay/bisexual groups to heterosexuals, without considering the heterogeneity of the non-heterosexual group (e.g., Jorm et al., 2002; McDonald, 2018). Indeed, few studies have considered questioning individuals (e.g., Birkett et al., 2009). These methodological decisions make it difficult to examine possible variations between different sexual minority groups.

Additionally, it is important to indicate that, to the best of our knowledge, most of these studies analyze difficulties by examining depression, anxiety disorders, and suicidal behavior. They do not include other indicators of mental health difficulties, such as psychotic experiences or general indicators of emotional and behavioral difficulties, which are prevalent and relevant in a stage of ontogenetic development such as adolescence (Ortuño et al., 2018). Furthermore, it has become particularly important to analyze mental health not only from a risk-based approach, but also from an approach focused on health, well-being, and quality of life (Malhi et al, 2019; Oliva et al., 2010; Park et al., 2004). Therefore, it would be necessary to incorporate variables in this direction, such as psychological well-being and self-esteem.

In line with this need to adopt a positive approach, it is important to note that the potential impact of social discrimination depends on the balance between risk and protective factors (Chaudoir et al., 2017; Cook et al., 2014). We need to examine how they interact to increase predictive strength (Cuijpers et al., 2021). Therefore, apart from investigating the factors (i.e., being a male) that can place a sexual minority individual at a greater risk of mental health problems, it is necessary to pay attention to constructs that can ameliorate and reduce the stress associated with stigma. One of the most well-known and consolidated protection factors is social support. As Bostwick et al. (2014) proposed, social support may buffer the negative effects of identity-based stressors such as sexual orientation.

Particularly, family support is fundamental in the development of the adolescent's sense of self, and it is especially relevant in sexual minority adolescents, who typically face more stress and violence throughout their youth (Myers et al., 2020). Specifically, previous studies have found that perceived support from family could play a protective role against some indicators of poor mental health, such as suicidal behavior and substance use or abuse (Mustanski & Liu, 2013; Padilla et al., 2010). Analyzing the protective role of family support could help to identify the needs of these adolescents and provide the basis for the development of workable interventions to support these youth.

Consequently, two objectives guide the present study. First, the purpose is to examine, in a representative sample of adolescents, whether the sexual orientation is related to an increased risk of mental health problems and poor psychological well-being. We analyze the relationship between the sexual orientation and indicators of emotional and behavioral problems, depression symptoms, psychotic-like experiences, suicidal behavior, personal well-being, and self-esteem. We also examine differences in mental health indicators across four sexual orientation subgroups and gender. Second, the possible moderation effect of parental support between the sexual orientation and suicidal behavior is also analyzed. Moreover, we will also introduce participants´ gender as a potential moderator in this model. In other words, we will examine whether this moderation is different for boys and girls.

We hypothesize that non-heterosexuals, compared to heterosexuals, will show poorer mental health indicators. Moreover, based on previous literature, bisexual participants and boys are expected to show weaker psychological well-being. Additionally, we hypothesize that levels of parental support would moderate the association between sexual minority status on adolescents' mental health. The moderated moderation by gender is considered exploratory, given the scarcity of previous research.

Method

Participants

Stratified random cluster sampling was conducted with the classroom as the sampling unit from a population of 15000 students in the region of La Rioja (northern Spain). The layers were created as a function of the geographical zone and the educational stage. An initial sample was composed of 1972 students. Students with more than one point (n = 146) on the Oviedo Infrequency Scale-Revisited (Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2019) or an age of more than 19 years (n = 36) were eliminated. Thus, the final sample was composed of 1790 students, 816 boys (45.6%), 961 (53.7%), girls and 13 (0.7%) with gender diversity. Regarding sexual orientation, measured by the sexual attraction, the results revealed that 1640 participants (92.3%) reported being other-gender attracted or mostly other-gender attracted, 46 (2.6%), same-gender attracted or mostly same-gender attracted, 49 (2.8%) both-gender attracted, and 42 (2.5%) questioning or unsure of their sexual orientation. Adolescents belonged to 30 schools and a total of 98 classrooms. Mean age was 15.70 years (SD= 1.26), with ages ranging between 14 and 18 years. Distribution of nationality was as follows: 89.4% Spain, 2.5% Romania, 1.9% Central and South American countries (Bolivia, Argentina, Colombia, and Ecuador), 1.4% Morocco, 0.8% Pakistan, 0.3% Portugal, and 3.8% other countries.

Instruments

Scale of Sexual orientation

To examine sexual orientation, a modified version of the Kinsey Scale (Kinsey et al., 1948) was used. The Kinsey Scale is a widely used index for measuring heterosexual and lesbian/gay behavior, and it introduces distinct sexual-orientation categories, designating a sexual continuum ranging from exclusively opposite-sex to exclusively same-sex attraction, with degrees of non-exclusivity in between. Participants were presented with the sentence “Normally you feel physical and loving attraction to..”, and they were asked to choose one option from the following: 1) always attracted to boys, 2) most of the time attracted to boys and sometimes to girls, 3) attracted to boys and girls similarly, 4) most of the time attracted to girls and sometimes to boys, 5) always attracted to girls, 6) I am not sure. Although some researchers (e.g., Haslam, 1997; Savin-Williams, 2014) claim that sexual orientation is best represented by a continuum, for methodological reasons (too many categories could have the effect of limiting the sample in each category) and following other sex researchers (e.g., Bailey et al., 2016), four categories were defined as sexual attraction patterns: heterosexual (options 1 and 2 for girls and 4 and 5 for boys), lesbian/gay (options 1 and 2 for boys and 4 and 5 for girls), bisexual (option 3 for boys and girls), and questioning.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (Goodman, 1997)

The SDQ is a self-report questionnaire that is widely used for the assessment of different emotional and behavioral difficulties related to mental health in adolescents. It is made up of a total of 25 statements distributed across five subscales: Emotional symptoms, Conduct problems, Hyperactivity, Peer problems, and Prosocial behavior. The first four subscales yield a Total difficulties score. Sentences are presented in a Likert-type response format with three options (0 = not true; 1= somewhat true; 2 = certainly true). The Spanish version for adolescents was used in this study (Ortuño-Sierra et al., 2015). In this study the ordinal alpha for the Total difficulties score was .84, ranging between .71 and .75 for the SDQ subscales.

Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale-Short Form (RADS-SF) (Reynolds, 2002)

The RADS-SF is a self-report that measures the severity of depressive symptomatology in adolescents. It consists of 10 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = almost never; 4 = almost always). In this study the Spanish version for adolescents was used (Ortuño-Sierra et al., 2017). The ordinal alpha for the total score for the present study was .89.

Prodromal Questionnaire-Brief (PQ-B) (Loewy et al., 2011)

The PQ-B is a self-report instrument composed of 21 items that assess prodromal symptoms of positive psychosis. The items are formulated in a true/false dichotomous format. If the participant answers the item affirmatively, he/she must indicate the degree of concern or discomfort caused by the experience on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). A higher score indicates a greater number of psychotic experiences, as well as greater severity. In the present study, Spanish version was used (Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2021), with an ordinal alpha of .91.

Adolescent Suicidal Behavior Assessment Scale (SENTIA) (Díez-Gómez et al., 2020)

SENTIA is a tool designed and validated for the assessment of suicidal behavior in adolescents. It is composed of 16 items in a dichotomous format (yes/no). Its bifactor structure is specified in a general suicidal behavioral factor plus three specific factors (Ideation, Communication, and Act/Planning). In the present study, the ordinal alpha value for the total score was .91, .92 for Ideation, .84 for Communication, and .94 for Act/Planning.

Personal Well-being Index-School Children (PWI-SC) (Cummins & Lau, 2005)

This scale contains eight items, with response options ranging from 0 (completely dissatisfied) to 10 (completely satisfied). The PWI-SC items assess subjective satisfaction with a specific area of life in a relatively generic and abstract way. The first item on the scale analyzes "life as a whole". The other seven items assess satisfaction with different life domains: standard of living, health, life achievements, relationships, safety, community-connectedness, and future security. The Spanish version of the PWI-SC was used in the present study (Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2018), where Cronbach's alpha for the total score was .83.

Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (RSS) (Rosenberg, 1965)

This instrument was developed to assess self-esteem. It consists of 10 items scored on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree”; 4 = “strongly agree”). The Spanish version (Oliva et al., 2011) was used in the present study. The scale showed good reliability in this sample (α = .87).

Parental Support

A measure derived from the ESTUDES survey (Survey on drug use in Secondary Education in Spain) and the ESPAD questionnaire (European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs) was used to analyze "parental regulation" and "parental emotional support". The original version is composed of five items. Four items are designed to assess parental regulation (rule-setting and monitoring), and they were adapted from a parental-control scale developed by Alsaker et al. (1991) and modified by Thorlindsson and Bjarnason (1998). Of these four items, two items measure parental rule-setting (“My parent(s) set definite rules about what I can do at home /outside the home”) and two items allow to evaluate parental monitoring (“My parent(s) whom I am with in the evenings”, “My parent(s) know where I am in the evenings”). Finally, a fifth item is derived from Bjarnason (1994) and evaluates parental emotional support (“I can easily get warmth and caring from my mother and/or father”). The scale is answered in a dichotomous format (1 = always, almost always; 2 = sometimes, rarely, or never). For this study, only the monitoring and emotional support items were included as a measure of parental support.

Oviedo Infrequency Scale-Revised (INF-OV-R) (Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2009; Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2019)

This scale allows to detect participants who respond in a random, pseudorandom, or dishonest manner. It is composed of 10 items. Students with two or more incorrect responses were eliminated from the sample.

Procedure

First, a researcher visited the headmasters of the randomly selected schools and explained the research project. Those who agreed to participate received informed consent forms for participants and parents (participants under 18). Subsequently, the research team visited the schools. They administered the assessment tools collectively through personal computers in groups of 10 to 30 students during normal school hours (50 minutes) and in a classroom especially prepared for this purpose. The study fulfilled the ethical values for human research and was approved by the Educational Government of La Rioja and the Ethical Committee of Clinical Research of La Rioja (Ref. CEImLAR P.I. 337). Participants were informed of the confidentiality of their responses and the voluntary nature of the study.

Data Analyses

First, descriptive statistics for all the study variables were calculated.

Second, the effects of sexual orientation and gender on mental health and the personal well-being indicators were analyzed using multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA). Age was used as covariate. Partial eta squared (partial η²) was used to calculate effect size.

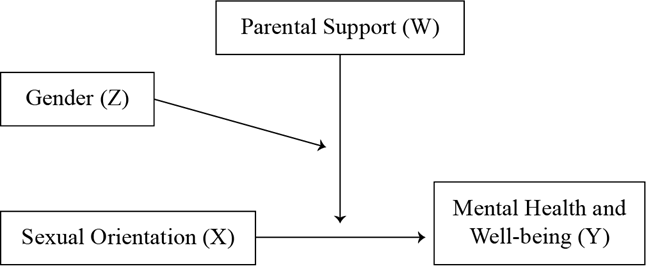

Third, moderated moderation analyses were conducted. The PROCESS macro for SPSS was used (Hayes, 2013). The hypothesized moderated moderation model examined whether the effect of sexual orientation (X) on mental health and well-being indicators (Y, SDQ, RADS-SF, PQ-B, SENTIA, PWI-SC, RSS) was moderated by parental support (W), and whether this moderation was different for boys and girls (Z, gender as a moderator). To control for sources of covariation within the moderation model, age in years was included as a covariate. Figure 1 represents the conceptual diagram of this model.

To test this model and considering the multi-categorical nature of the independent variable (X, sexual orientation), seven regression models were estimated for each of the seven mental health and well-being indicators using an indicator or dummy system and following Hayes & Montoya's (2017) recommendations for moderation analysis with multi-categorical independent variables. According to these authors, a multi-categorical independent variable with k = 4 categories (i.e., heterosexual, lesbian/gay, bisexual, questioning) can be used as a predictor in a regression if it is properly represented with k - 1 = 3 variables coding the groups represented in the multi-categorical variable. In the present case, when using an indicator or dummy system, the heterosexual orientation was the baseline category (X1 = X2 = X3 = 0), with X1 as the lesbian/gay category (X1 = 1, X2 = X3 = 0), X2 as the bisexual category (X1 = 0, X2 = 1, X3 = 0), and X3 as the questioning category (X1 = X2 = 0, X3 = 1). The three-way interactions were tested by using the Johnson-Neyman technique implemented in PROCESS (Hayes & Montoya, 2017). The analyses were carried out using the statistical package SPSS v26 (IBM Corp Released, 2019) and the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2013).

Results

Sexual Orientation, Gender, and Mental Health

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) for all the study variables by sexual orientation and gender.

Table 1. Means and Standard Deviations for All the Mental Health Indicators by Sexual Orientation and Gender.

| Heterosexual (He) | Lesbian/Gay (LG) | Bisexual (B) | Questioning (Q) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | T n = 1640 | G n = 864 | B n = 776 | T n = 46 | G n = 24 | B n = 22 | T n = 49 | G n = 41 | B n = 8 | T n = 42 | G n = 32 | B n = 10 |

| SDQ | 10.73 (4.99) | 11.44 (5.07) | 9.93 (4.79) | 14.11 (5.93) | 15.64 (6.85) | 12.45 (4.28) | 14.29 (5.03) | 14.22 (4.41) | 14.63 (7.89) | 12.12 (5.51) | 11.5 (5.06) | 14.10 (2.17) |

| RADS-SF | 16.13 (4.27) | 16.81 (4.59) | 15.37 (3.76) | 19.33 (5.55) | 21.17 (5.99) | 17.32 (4.30) | 20.41 (5.80) | 20.85 (5.73) | 18.13 (5.99) | 17.57 (4.04) | 17.97 (4.05) | 16.30 (3.95) |

| PQ-B | 5.10 (4.19) | 5.70 (4.24) | 4.44 (4.03) | 8.26 (4.23) | 8.67 (4.25) | 7.82 (4.68) | 7.80 (4.68) | 7.66 (4.54) | 8.50 (5.61) | 6.17 (3.75) | 6.03 (4.00) | 6.60 (2.95) |

| SENTIA | 1.05 (2.41) | 1.29 (2.69) | .78 (2.02) | 2.74 (3.73) | 3.92 (4.09) | 1.45 (2.87) | 3.37 (4.23) | 3.63 (4.35) | 2.00 (3.42) | 1.12 (1.97) | 1.38 (2.17) | .30 (.68) |

| PWI-SC | 7.85 (1.78) | 7.55 (1.88) | 8.18 (1.61) | 6.74 (2.43) | 6.00 (2.52) | 7.55 (2.09) | 6.43 (2.36) | 6.29 (2.40) | 7.13 (2.17) | 7.10 (1.92) | 7.00 (2.10) | 7.40 (1.27) |

| RSS | 31.07 (5.43) | 29.68 (5.49) | 32.62 (1.12) | 27.63 (7.04) | 25.17 (6.77) | 30.32 (6.45) | 27.35 (5.68) | 27.10 (5.59) | 28.63 (6.35) | 29.98 (5.17) | 29.59 (5.62) | 31.20 (3.29) |

| Parental Support | 2.58 (.74) | 2.77 (0.67) | 2.47 (.80) | 2.26 (1.08) | 2.08 (1.21) | 2.45 (.91) | 2.45 (.77) | 2.46 (.78) | 2.37 (.74) | 2.62 (.76) | 2.78 (.42) | 2.10 (1.29) |

Note.SDQ = Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; RADS-SF = Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale-Short Form; PQ-B = Prodromal Questionnaire-Brief; SENTIA = Adolescent Suicidal Behavior Assessment Scale; PWI-SC = Personal Well-being Index-School Children; RSS = Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale; T = Total; G = Girls; B = Boys.

A MANCOVA was carried out with mental health and protective indicators as dependent variables (i.e., SDQ, RADS-SF, PQ-B, SENTIA, PWI-SC, RSS, Parental Support), sexual orientation and gender as fixed factors, and age as covariate.

The MANCOVA revealed statistically significant main effects for sexual orientation group [Wilk´s λ= 0.960, F (21, 5037.09)= 3.457;p< 0.001;partial η²= .014] and gender [Wilk´s λ= 0.981, F (7, 1754)= 4.777;p< .001;partial η²= .019]. It also showed a significant interaction between sexual orientation and gender [Wilk´s λ= 0.978, F (21, 5037,09)= 1.827;p< .05;partial η²= .007]. Small effect sizes were found (see Table 2).

Table 2. ANOVAs for All the Study Variables for Sexual Orientation and Gender.

| Sexual Orientation | Gender | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | F | p | Partial η2 | Post hoc comparisons | F | p | Partial η2 | Post hoc comparisons |

| SDQ | 12.758 | <.001 | .021 | He < LG, B; Q < B | .401 | .527 | .000 | |

| RADS-SF | 13.488 | <.001 | .022 | He < LG, B, Q; Q < B | 14.151 | <.001 | .008 | F > M |

| PQ-B | 7.410 | <.001 | .012 | He < LG, B, Q; Q < Ho | .118 | .731 | .000 | |

| SENTIA | 13.746 | <.001 | .023 | He, Q < LG, B | 14.722 | <.001 | .008 | F > M |

| PWI-SC | 9.942 | <.001 | .017 | He > LG, B, Q | 10.302 | .001 | .006 | F < M |

| RSS | 9.410 | <.001 | .016 | He > LG, B, Q; Q > B | 12.856 | <.001 | .007 | F < M |

| Parental Support | 3.012 | .029 | .005 | He, Q > LG | 1.676 | .196 | .001 | |

Note.SDQ = Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; RADS-SF = Reynolds Adolescent Depression Scale-Short Form; PQ-B = Prodromal Questionnaire-Brief; SENTIA = Adolescent Suicidal Behavior Assessment Scale; PWI-SC = Personal Well-being Index-School Children; RSS = Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale. He = Heterosexual; LG = Lesbian/Gay; B = Bisexual; Q = Questioning; G = Girls; B = Boys.

Bonferroni post-hoc analysis revealed that lesbian/gay and bisexual groups scored significantly higher on emotional and behavioral problems, depression symptoms, psychotic-like experiences, and suicidal behavior, and lower on personal well-being and self-esteem, compared to the heterosexual group. The lesbian/gay group also scored lower on parental support than the heterosexual and questioning groups, and higher on psychotic-like experiences than the questioning group. In addition, the bisexual group scored significantly higher on emotional and behavioral problems and depressive symptoms, and lower on self-esteem, compared to the questioning group.

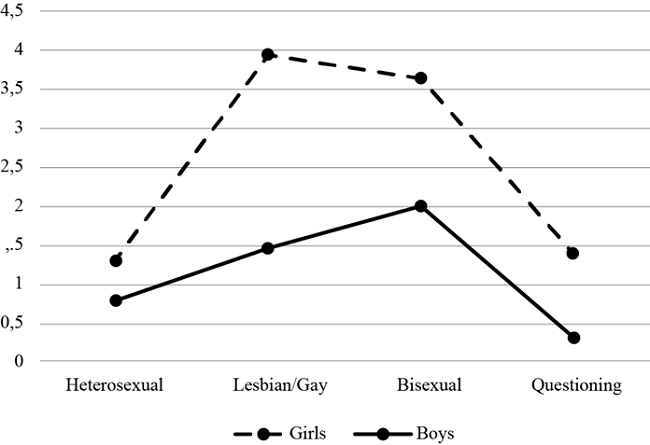

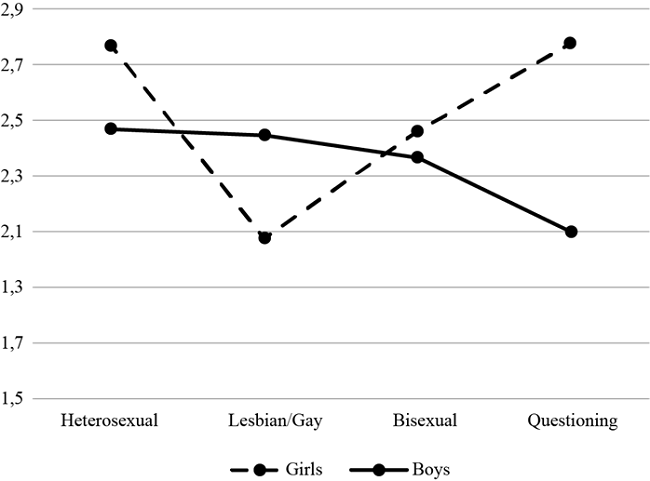

Independently of the sexual orientation group, girls scored significantly higher than boys on depressive symptoms suicidal behavior, and lower on personal well-being and self-esteem. Two interactions were found between sexual orientation and gender: one for suicidal behavior (F (3, 1760)= 2.755;p= .041;partial η²= .005) and the other for parental support (F (3, 1760)= 3.250;p= .021;partial η²= .006). Figure 2 and Figure 3 show these interactions. Results indicate that the risk of suicidal behavior is higher when the adolescent is a lesbian or bisexual girl. Additionally, results showed that, compared to other groups, lesbian girls and questioning boys presented the lowest scores on parental support.

Moderating Role of Parental Support and Gender

To test the potential moderating role of parental support in the relationship between sexual orientation and mental health indicators, several regression models were conducted. Given the results for the differences between boys and girls on mental health outcomes, independently of sexual orientation, and based on previous studies, gender was also included as a potential moderator. Thus, seven moderated moderation models examined whether the effect of sexual orientation (X) on the different indicators of mental health (Y) was moderated by parental support (W), and whether this moderation was gender dependent (Z) (as represented previously in Figure 1). Age in years was included as a covariate.

Table 3 presents the results of these moderated moderation models. To facilitate interpretation, only significant simple and interaction effects are shown. As Table 3 shows, same-gender attraction had a positive association with emotional and behavioral problems, symptoms of depression, psychotic-like experiences, and suicidal behavior, and a negative association with personal well-being. Neither the bisexual nor the questioning orientation had an effect on any of the seven mental health indicators. Parental Support had a negative effect on suicidal behavior. Gender influenced all the dependent variables. This effect was positive for the indicators of psychological maladjustment (i.e., SDQ, RADS-SF, PQ-B and SENTIA) and negative for the indicators of well-being (i.e., PWI-SC and RSS). Thus, being a girls was a predictor of mental health difficulties. Age had a positive effect on all the dependent variables except PQ-B and RSS. An interaction was showed between the lesbian/gay group and Parental Support for PQ-B, SENTIA, and PWI-SC, and with gender for PQ-B and SENTIA. Parental Support also showed an interaction with gender for all the dependent variables, with the exception of SDQ. A three-way interaction between the lesbian/gay group, parental support, and gender was found for SENTIA. Given the purpose of the tested moderated moderation models, this three-way interaction was further explored.

Table 3. Regression Model Coefficients (Standard Errors in Parentheses).

| SDQ | RADS-SF | PQ-B | SENTIA | PWI-SC | Self-esteem | |

| Coefficient (SE) | ||||||

| Intercept | 4.18 (1.97)* | 11.18 (1.69)** | --- | -3.37 (.99)* | 11.14 (.71)** | 39.04 (2.11)** |

| Lesbian/Gay | --- | --- | 15.32 (5.52)* | 11.42 (3.26)* | -5.30 (2.35)* | --- |

| Parental Support (PS) | --- | --- | --- | -.68 (.25)* | --- | --- |

| Gender | 3.49 (.89)** | 3.48 (.76)** | 2.87 (.75)** | 2.69 (.44)** | -1.59 (.32)** | -6.01 (.95)** |

| Age | .30 (.09)** | .17 (.08)* | --- | .11 (.05)* | -.12 (.03)** | --- |

| Lesbian/Gay x PS | --- | --- | -4.49 (2.13)* | -4.90 (1.26)* | 2.01 (.91)* | --- |

| Lesbian/Gay x Gender | --- | --- | -7.02 (3.17)* | -4.74 (1.87)* | --- | --- |

| Parental Support x Gender | -.65 (.33)* | -.70 (.28)* | -.55 (.28)* | -.80 (.17)** | .34 (.12)* | 1.10 (.35)* |

| Lesbian/Gay x PS x Gender | --- | --- | --- | 2.47 (.73)* | --- | --- |

| Model R2 | .098** | .124** | .074** | .097** | .116** | .126** |

| Interaction ( R2 | .001 | .003 | .003 | .007* | .005* | .002 |

Note. *p < .05;

**p < .001.

Only significant results are reported (though all were tested).

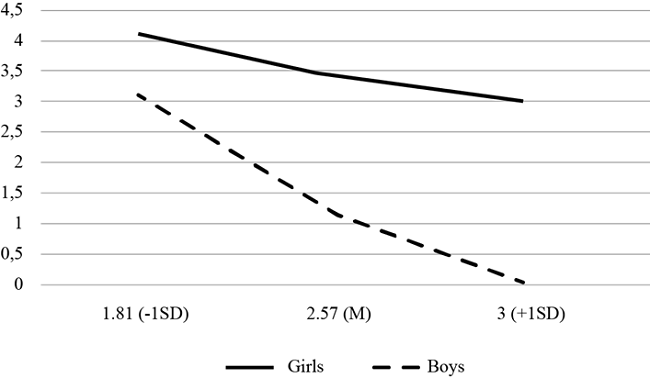

The three-way interaction was formally tested by using the Johnson-Neyman technique implemented in PROCESS (Hayes & Montoya, 2017). Figure 4 plots the conditional effect of the lesbian/gay group on suicidal behavior (SENTIA) as a function of parental support and gender. In men, the effect of the same-gender attraction on SENTIA was moderated by parental support [F (3, 1760) = 6.875, p <.001], whereas in girls parental support did not moderate the effect of the same-gender attraction on suicidal behavior [F (3, 1760) = .5028, p = .680]. The effect of the same-gender attraction on suicidal behavior in men with low parental support was positive and significant [Effect = 2.01, SE = 0.64, p < .01], whereas it was negative and non-significant for men with high parental support [Effect = -0.61, SE = 0.61, p = .32].

Discussion

Previous research indicates that sexual minority individuals can experience higher levels of mental health difficulties than heterosexual people. Describing these difficulties, delineating high-risk subgroups, and identifying potential protective factors might lead to a deeper understanding of the needs of these groups and guide future interventions aimed at promoting their emotional well-being. Thus, the present study was designed to analyze the relationship between sexual orientation and mental health indicators in a representative sample of adolescents. Additionally, we intended to examine the potential buffering role of parental support on mental health, as well as the potential moderator effect of the participant´s gender in these relationships.

Regarding the first study goal, results show that sexual minority individuals reported poorer mental health than heterosexuals on a range of indicators of psychological well-being and mental health. Same-gender and both-gender attraction was associated with higher emotional and behavioral problems, symptoms of depression, psychotic-like experiences, and suicidal behavior, than the other-gender attraction. Moreover, adolescents who report bisexual and lesbian/gay attraction presented lower personal well-being and self-esteem than those from the heterosexual group. Prior research conducted in adolescents and adults found similar results, indicating a higher prevalence of psychological problems among sexual minority groups. For example, Raifman et al. (2020) found that adolescents from sexual minorities were three times more likely to attempt suicide compared to heterosexual students. Gonzales and Henning-Smith (2017), using a national survey in the USA, indicated that lesbian/gay and bisexual adults were more likely to experience a range of impaired health outcomes, including mental distress and depression.

The present study also reveals a similar situation for different sexual minority groups: bisexual, lesbian/gay, and questioning. In fact, disparities were found equally in bisexual and lesbian/gay adolescents, with no differences between them. These results are congruent with some studies that found no differences between these groups. For example, Denny et al. (2016) found that bisexual students reported the highest rates of suicide attempts, compared to lesbian/gay students and heterosexuals, but similar rates of general suicidality and depressive symptoms as lesbian/gay students, with both groups differing significantly from the heterosexual group. However, research generally reveals more disparities in bisexual groups than in lesbian/gay groups, frequently showing that, compared to heterosexuals and gay men, bisexuals reported some of the worst mental health outcomes in both adults (Bostwick et al., 2010; Jorm et al., 2002) and adolescents (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2014; Marshal et al., 2013).

This study included the category of questioning, or youths who are unsure about their sexual orientation, in the analysis. Results showed that, excluding suicidal behavior, questioning youths presented poorer mental health indicators than the heterosexual group. Evidence about this group is limited. Most studies, even the most recent ones, tend to omit questioning people from their analyses (e.g., Bostwick et al., 2014; Denny et al., 2016). Nevertheless, when studies include this category, results also show higher rates of mood and anxiety disorders (Birkett et al., 2009; Bostwick et al., 2010) and risk of suicide (Birkett et al., 2009; Hatzenbuehler, 2014), compared to the heterosexual group.

Differences among studies could be explained by the mental health indicators examined and the measures used. Moreover, further research is required in this regard, given that most of the studies tended to group non-heterosexual individuals together for data analysis. According to some authors (e.g., Jorm et al., 2002; McDonald, 2018), previous research may have overstated the risk of mental health problems in some specific groups.

Regarding gender, the present study showed that girls reported higher scores on symptoms of depression and suicidal behavior and lower scores on psychological well-being and self-esteem. However, this effect was not moderated by the sexual orientation. Except for suicidal behavior, for which bisexual and lesbian girls showed higher risk. Coherent with this finding was the study conducted by Almazan et al. (2014) with young adults. They found that the sexual minority status had significant associations with increased suicidal thoughts in women and men, but with increased suicide attempts only in women. Padilla et al. (2010) also found that a high percentage of sexual minority youths had seriously thought about taking their own life, with the highest percentage found in lesbian youths. In this regard, our study failed to show the repeated finding about gender and sexual orientation. As McDonald (2018) highlights, the scientific literature generally shows that men from sexual minorities have a higher risk of mental health difficulties (Fergusson et al., 2005; Plöderl & Tremblay, 2015). For instance, King et al. (2008) found that lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts was especially high in gay and bisexual men. Bostwick et al. (2010) detected that being a man from a sexual orientation minority was associated with a higher prevalence of lifetime mood and anxiety disorders. For women, the results were much inconsistent. Therefore, differences based on gender need a deeper analysis in studies that distinguish between sexual orientation subgroups, as well as analyses that differentiate adults from adolescents and a wide variety of mental health indicators.

The present study also revealed differences in personal well-being and self-esteem. However, research on these variables is quite limited. Padilla et al. (2010) observed higher levels of self-esteem in gay, lesbian, and bisexual adolescents. Espada et al. (2012) found that no heterosexual adolescents presented a better self-concept of physical ability and a lower self-concept of honesty than heterosexuals. These hypotheses require a deeper analysis in future research.

In relation to the second study goal, we intended to examine the potential buffering role of parental support in mental health and the possible moderator effect of participants' gender on this relationship. Results indicated that lesbians were more exposed to risk, as they did not seem to be protected by parental support. For gays, however, parental support worked as a buffer of the impact of same-gender attraction on suicidal behavior. This result is in line with other studies that show the protective power of parental support against mental health problems. For example, Padilla et al. (2010) established that adolescents' perception of parental acceptance of their sexual identity (especially the mother´s acceptance) played a protective role against LGB suicidal ideation and drug use in the context of life stressors. Mustanski and Liu (2013) showed that parental support was negatively related to the lifetime history of attempted suicide, hopelessness, and depression symptoms. Otherwise, lack of parental support and caregiver rejecting behaviors have been associated with serious health problems and less educational achievement (D'Augelli et al., 2006; Ryan et al., 2009, 2018). Hence, parental support could be an essential source of help for people facing this crucial developmental moment with the stressful challenge of defining themselves as sexually diverse, at least for boys.

Results seem to support the initial proposal by Meyer (2003), followed by multiple authors such as Baiocco (2021), Bostwick et al. (2014), or Hatzenbuehler (2009). According to these authors, mental health differences are not determined solely by individual factors (i.e., personality), but they are also socially derived and determined by conditions in the environment and the complex interplay between individual factors and the socio-cultural context where individuals reside (Douglass & Conlin, 2020). Prejudice and discrimination behaviors could act as stressors in the lives of minority people. In turn, exposure to multiple forms of discrimination could increases the likelihood that they will be exposed to discriminatory treatment (Grollman, 2012, 2014).

Results derived from the present research also suggest that parental support could moderate the impact of these stress conditions on mental health for some groups. As Mustanski and Liu (2013) acknowledged, designing interventions that strengthen sexuality support and involve families could be a way to increase the well-being and mental health of LGBT adolescents. Undoubtedly, additional research is needed to explore what kind of support (i.e., from peers, family, or school) and directed to which subgroup (depending on their sexuality or gender identity) could help adolescents face their developing individuality under stress. Educational settings for these interventions can provide the right conditions, given that safe school environments have been associated with improved sexual minority adolescent mental health (Denny et al., 2016; Hatzenbuehler et al., 2014; Poteat et al., 2013).

Even beyond the LGTB reality, it must be taken into consideration models of suicidal behavior both in the explanation and understanding of the complexity of the suicidal behavior process. In that regard, the additive effect of multiple interrelated risk factors that an individual may face across individual, family, and environmental contexts (Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2022a, 2022b), must be acknowledged. In accordance with this, suicide prevention strategies should adopt a socio-ecological perspective that involves multiple level interventions different in all the settings within the individual develops (Fonseca-Pedrero et al., 2022a), especially in the family context.

The present study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, self-reports, with their well-known biases, were used. Second, as previous research has indicated (e.g., Wolff et al., 2017), sexual orientation is a complex, multidimensional construct (Fernández et al., 2006) often composed of identity, attraction, and behavior. This study only assessed sexual attraction and this methodological decision must be taken into consideration. Third, we used a cross-sectional design, and so we cannot establish the causal pathways for the observed associations between sexual orientation and health. Longitudinal studies would show whether sexual orientation is causally related to mental health disparities. Fourth, as other researchers have pointed out (e.g., Baiocco et al., 2014; Bostwick et al., 2010; Gonzales & Henning-Smith, 2017; Jorm et al., 2002; Martxueta & Etxeberria, 2014) some potentially important risk factors, such as feelings of stigma, non-disclosure of sexual orientation to significant others, or experiences of discrimination and victimization such as bullying or childhood sexual abuse, were not measured and are expected to influence the relationship between sexual orientation and health outcomes. Finally, the sample was limited to a particular geographical region in Spain, therefore impacting the generalizability of the results.

Notwithstanding these limitations, this study adds to the mounting evidence of health disparities based on sexual orientation. A large amount of previous research has relied on data from non-random convenience samples of LGBT people, especially those associated with LGBT-friendly organizations. However, the present study was carried out with a representative sample of adolescents, with distinctions between sexual minority and gender groups. In addition, the study uses a wide set of validated measures to assess indicators of mental health and psychological well-being.

Taken together, our results suggest that sexual minority adolescents are at risk of unhealthy maturation, highlighting the need for developing workable interventions to support them.