Introduction

Epidemiological studies allowed us to conclude that the worldwide prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) ranges from 2% to 10% (Catalá-López et al., 2012; Danielson et al., 2018; Polanczyk et al., 2007; Rowland et al., 2002; Song et al., 2021). ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by pervasive inattentive symptoms (impaired attention abilities), disorganization, and impulsive/hyperactivity (American Psychological Association [APA, 2013]). A specific ADHD subtype (inattentive or hyperactive subtype) can be diagnosed depending on the predominance of inattentive or hyperactivity symptoms, while a combined subtype of ADHD can be diagnosed when an individual presents pervasive symptoms of both types (Epstein & Loren, 2013).

Several meta-analyses and systematic reviews have linked ADHD with violence proneness and/or antisocial behaviors, establishing a positive association between both (Mohr-Jensen & Steinhausen, 2016; Pratt et al., 2002; Saylor & Amann, 2016). From a neurodevelopmental perspective, the absence of a correct early ADHD diagnosis and its concurrent treatment during childhood might entail a considerable risk for the onset of antisocial behaviors during adolescence and adulthood, which is reflected by the number of arrests and/or incarcerations, as well as recidivism rates after incarceration or interventions (Mohr-Jensen & Steinhausen, 2016; Pratt et al., 2002; Saylor and Amann, 2016). Moreover, the type of violence perpetrated by ADHD individuals tend to be characterized by reactivity and/or impulsivity, more often perpetrated by individuals with a combined subtype ADHD (Saylor & Amann, 2016), that is, individuals with concurrent inattention and hyperactivity symptoms.

Due to the fact that emotional and behavioral dysregulation (e.g., violence proneness, antisocial behaviors…) tend to be affected by the severity of ADHD symptoms (Mansour et al., 2017), a correct diagnosis of ADHD becomes of great clinical interest as it could reduce reoffending or recidivism after an individual completes tailored interventions or their prison sentence (Loyer Carbonneau et al., 2021). In this regard, the rate of criminal recidivism decreased among those patients who were diagnosed with ADHD and were receiving their corresponding treatment (e.g., receiving stimulants, psychotherapy, etc.) (Buitelaar et al., 2014; Lichtenstein & Larsson, 2013; Pappadopulos et al., 2006). The deeper our knowledge regarding the main causes of violence (e.g., correct ADHD diagnosis and moderator factors), the better our ability for designing more specific interventions and therefore reducing recidivism rates.

In recent years, the importance of ADHD for perpetrating or being a victim of intimate partner violence (IPV) has been highlighted (Buitelaar et al., 2020; Buitelaar et al., 2014; Fang et al., 2010; Theriault and Holmberg, 2001; Wymbs et al., 2012; Wymbs et al., 2017). Most of this violence among heterosexual couples is perpetrated by male against their female partners. Estimates of worldwide prevalence of this kind of violence revealed that approximately 27% of women aged 15 to 49 years have suffered some type of physical or sexual violence from their male partner throughout their life (Martín-Fernández et al., 2019, 2020; World Health Organization [WHO, 2021]).

It cannot be concluded that ADHD necessarily or directly facilitates IPV perpetration. Alcohol and drug misuse and type B personality traits (e.g., antisocial, borderline, etc.), among others, may act as confounding factors, that is, ADHD in combination with the above-mentioned factors might drive individuals to carry out risky behaviors such as violence, and avoiding those confounding variables considerably diminishes the ability of ADHD to predict IPV (Buitelaar et al., 2020). However, these variables (e.g., alcohol or drug misuse, antisocial personality traits, etc.) do not offer too much information regarding the cognitive processing of surrounding information of individuals affected by this disorder. Therefore, it becomes important to explore cognitive variables that clarify how individuals with ADHD might be prone to violence, given that these processes are closely and/or directly related with behavioral and emotional regulation, which in turn, affect violence proneness.

Applying a cognitive model for understanding which mechanisms explain violence proneness in individuals affected by ADHD, it can be stated the existence of considerable differences between individuals affected by ADHD and those unaffected by this or other disorders in several cognitive domains such as IQ, processing speed, working memory, attention, cognitive flexibility, planning, and inhibition abilities (Loyer-Carbonneau et al., 2021; Pievsky & McGrath, 2018), as well as in facial emotion recognition (Bora & Pantelis, 2016). The broader the cognitive deficits in ADHD individuals, the higher their proneness to anger expression (McDonagh et al., 2019) and emotional dysregulations (Banaschewski et al., 2012). Additionally, cognitive deficits have also been associated with IPV proneness (Humenik et al., 2020; Romero-Martínez, Lila, et al., 2022; Romero-Martínez, Santirso, et al., 2022). This can be explained by a reduced ability to process surrounding information and act or make consequent decisions with this analysis. In other words, when IPV perpetrators present a lowered ability for processing emotional stimulus, verbalizing inner states, coping with stressful stimulus, or making decisions, there are a greater risk of IPV perpetration (Expósito-Álvarez et al., 2021; Howieson, 2019; Humenik et al., 2020; Lezak et al., 2012). Their low ability for coping with ambiguous stimulus (e.g., couple arguments, stressful workplace situations, etc.) might facilitate violence intake when those deficits are combined with other hostile cognitive schemas (e.g., low perceived severity of IPV, sexism, etc.; Juarros-Basterretxea et al., 2022; Martín-Fernández et al., 2022), and a lack of abilities for searching alternative ways to respond. Assessing neuropsychological variables might clarify the association between ADHD and IPV recidivism, which in turn, would help us to prevent or reduce it. Unfortunately, to date there is a gap in the scientific literature regarding how these variables explain the potential association between ADHD and IPV.

One of the main problems with IPV perpetrators is the considerable percentage of them that abandon standard batterer interventions prematurely (i.e., dropout; Arce et al., 2020; Lila et al., 2020; Santirso, Gilchrist, et al., 2020; Soleymani et al., 2018). This is a key problem for IPV perpetrators, as dropout constitutes a valuable factor when predicting IPV perpetrators' recidivism (Lila et al., 2019). Nonetheless, as far as we know, the usefulness of ADHD symptoms to explain dropout in IPV perpetrators has not yet been analyzed. However, there is evidence that highlights ADHD as a risk factor for recidivism (Buitelaar et al., 2014; Lichtenstein & Larsson, 2013; Pappadopulos et al., 2006) and points out how cognitive deficits might allow to partly explain IPV perpetrators' dropout and recidivism (Romero-Martínez et al., 2021; Romero-Martínez, Lila, et al., 2022; Romero-Martínez, Santirso, et al., 2022). Hence, it would be necessary to conduct empirical research to assess whether ADHD in combination with cognitive deficits in IPV perpetrators considerably increases our ability to explain dropout and recidivism in those men.

In sum, the present study was aimed primarily at answering three questions: 1) whether IPV perpetrators affected by ADHD would present a differentiated neuropsychological profile from IPV perpetrators without ADHD and, especially, in comparison with non-violent men (or controls). In line with what has been previously concluded in this field of research (Bora & Pantelis, 2016; Loyer-Carbonneau et al., 2021; Pievsky & McGrath, 2018), we expected that ADHD IPV perpetrators (combined type) would present higher cognitive impairments (i.e., working memory, attention, cognitive flexibility, planning abilities, and emotion decoding) than IPV perpetrators without ADHD and controls, but not in comparison with IPV perpetrators affected by ADHD inattentive type; 2) we also aimed to assess whether to abandon the intervention program before it ends (dropout) and recidivism was directly related to an ADHD diagnosis in IPV perpetrators; accordingly, based on previous empirical research in this field (Mohr-Jensen & Steinhausen, 2016; Pratt et al., 2002; Saylor & Amann, 2016), we hypothesized that the higher the severity of the diagnosis (e.g., ADHD combined subtype vs unaffected or inattentive subtype), the greater the dropout, and official recidivism rates; last, 3) the main novelty of this study was to measure whether neuropsychological impairments would mediate the association between ADHD symptoms with dropout and recidivism among IPV perpetrators. To date, a scarce number of studies have explored the mediator role of neuropsychological deficits between the above-mentioned variables. However, neuropsychological deficits have been demonstrated to have a considerable predictor value for dropout and recidivism in violent individuals, including IPV perpetrators (Hundozi et al., 2016; Meijers et al., 2017; Miura & Fuchigami, 2017; Norman et al., 2022; Romero-Martínez et al., 2021; Romero-Martínez, 2022; Sánchez de Ribera et al., 2021). Therefore, we consider that neuropsychological deficits, specifically executive functioning, would mediate the association between ADHD, specifically the combined subtype, with dropout and recidivism.

Method

Participants

The calculation of power analysis determined a minimum sample size of 385 participants for our study. This number was based on the male population in Spain, considering a confidence level of 95%, a margin error of 5% (α = .05, 1-β = .95), and a response distribution of 50% for generalized linear models (Maxwell & Delaney, 2004). From an initial sample of 445 participants who agreed to participate, only 427 were finally included in our study because they completed all the measures of interest for this study. Hence, the number of participants satisfied the statistical criterion for conducting this study.

Initially 340 IPV perpetrators were screened, but only 324 were finally included. The main cause for removing participants was the missing data on the neuropsychological variables. From 105 controls initially interviewed, only 103 were included. Two participants were removed because their performance in Conners Continuous Performance-III (CPT-3; Conners, 2015) presented a strong indication of ADHD symptoms and we did not have enough controls for an additional ADHD group.

IPV perpetrators were classified into ADHD subtype according to their performance in CPT-3. Men classified as combined subtype (n = 66) presented a strong indication of attention deficits and impulsivity. Moreover, they scored above 20 on the Plutchik Impulsivity Scale (Plutchik & Van Praag, 1989; Rubio-Valladolid et al., 1999). This diagnosis was later corroborated by facilitators from the CONTEXTO program according to criterion established in the DSM-5 for diagnosing ADHD (APA, 2013). Participants were classified as ADHD inattention subtype (n = 95) when they only presented a strong indication for attention deficits, without impulsivity and scored below 20 on the Plutchik Impulsivity Scale. This diagnosis was again corroborated by facilitators from the CONTEXTO program. Last, three IPV perpetrators were classified as impulsive type and were removed from statistical analysis because it was not possible to form an additional group.

To take part in this study, participants had to be over 18 years old and have no physical or mental/cognitive problems (e.g., schizophrenia, severe traumatic brain injury, strokes with severe brain damage, etc.) and/or substance use disorders.

IPV perpetrators received an alternative measure to prison as part of their IPV sentence on the condition that they would attend an intervention program designed specifically for this kind of violent population. These men received this alternative measure because their prison sentence was under two years and they had no previous criminal record. IPV perpetrators received a court mandated psycho-educational and community-based treatment program (CONTEXTO) at our university. The CONTEXTO intervention is a cognitive behavioral treatment that also includes motivational strategies to increase treatment compliance and promote change, which has been manualized (see Lila et al., 2018; Romero-Martínez et al., 2019; Santirso, Lila et al., 2020), for a more exhaustive description of this intervention.

Regarding controls, advertisements to take part in a study in our university were posted online. As a result, men participating in the study were first contacted by e-mail. Subsequently, an initial interview was arranged for screening purposes. The inclusion criteria for this control group were not having a criminal record of violence against their partner or another individual, which was verified based on a criminal record certificate issued by a public institution; scoring below 1 on the Conflict Tactics Scale-II (Muñoz-Rivas et al., 2007; Straus et al., 1996) and absence of ADHD (did not present strong indication for ADHD in CPT-3 performance), and scoring below 20 in the Plutchik Impulsivity Scale (Plutchik & Van Praag, 1989; Rubio-Valladolid et al., 1999). In addition, they had to present similar age and sociodemographic characteristics to those of the IPV perpetrators included in our study.

Participation in the study was voluntary, and participants previously gave their written informed consent, following the Declaration of Helsinki. IPV perpetrators were informed that refusing to participate in our study would not affect their legal status or their sentence. This project was also approved by the University Ethics Committee (assigned codes: H1348835571691 and H1537520365110).

Procedure

After signing their informed consent before an initial telephone screening process, all men participated in two sessions in the Faculty of Psychology. Information for IPV perpetrators was collected before starting the Standard Batterer Intervention Program (CONTEXTO program). During the first session, participants were interviewed to exclude any individuals with physical or mental illnesses that could seriously disrupt the results of our study. Sociodemographic and drug misuse data were collected during this session and the CPT-3 was administered to classify participants according to their performance, impulsivity score, and facilitators' criterion. During a second session, a set of neuropsychological tests were administered. This session took place the following day between 10 a.m. and 2 p.m., to minimize possible effects of fatigue later in the day. After arriving at the laboratory, participants were taken to a room where the neuropsychological tests and self-reports were administered, which took approximately 90 minutes.

Finally, dropout data was collected across the duration of the CONTEXTO program (35 weeks, one day per week), and official recidivism data was based on official records collected during the first year after the intervention program ended.

Instruments

ADHD symptoms were measured with Conners' Continuous Performance Test-III (CPT-3; Conners, 2015), employed to assess inattention, impulsivity, sustained attention, and vigilance. This instrument is considered the ‘gold standard' for diagnosing ADHD, as these patients tend to present a characteristic profile (Lee et al., 2008). For 14 minutes, participants have to press the space bar on the computer when any letter except “X” appears on the screen.

Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test (K-BIT; Kaufman & Kaufman, 1997)

This test was used for assessing verbal and non-verbal abilities (IQ) and contains two subtests: vocabulary and matrices. The vocabulary subtest measures expressive vocabulary and definitions, whereas the matrices consist of a series of abstract figures in which participants must understand the logic that follow the sequence of figures that researchers present to them. This screening test is useful to assess intelligence in children as well as in adolescents and adults and requires a minimum of 15 and a maximum of 90 minutes for its administration.

Digit Span Subscale of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale-III (WAIS-III; Wechsler, 1999)

This scale was used to assess working memory. Participants have to repeat the sequence of digits after a researcher reads them in forward and backward order. For this study, we employed the total score (forward + backward subscales).

TF-A-S Verbal Phonemic Fluency Task

It was employed for verbal fluency. To complete this test, it is necessary to verbalize as many words as possible for each letter (F, A, and S) for 60 seconds. In addition, verbal semantic fluency was assessed in a similar way. Individuals had to name as many animals as possible in 60 seconds. In both cases, a total score was obtained by adding one point for each correct response. Thus, the higher the total score, the better the verbal phonemic and semantic fluency (Del Ser Quijano et al., 2004).

Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST)

It was used to measure cognitive flexibility. This test consists of four stimulus cards and 128 response cards containing various stimulus such as colors, shapes, and numbers of figures (Heaton et al., 1993). For this study, we employed the number of trials, total errors, perseverative errors, and number of categories completed. Low cognitive flexibility or worse performance is characterized by a high number of trials and errors, as well as a low number of completed categories.

Key Test

This test was considered for measuring planning abilities, which is part of the behavioural assessment of the dysexecutive syndrome (Wilson et al., 1996). Participants have to draw an itinerary to discover a lost key. For this test, we included three scales: the total score and the time spent planning and executing the task. A higher score, meaning spending shorter times is interpreted as better planning abilities.

Eyes Test

The Eyes Test was employed to measure emotion decoding. Participants were shown 36 black and white photographs that show the eye region of different men and women and asked to indicate which feeling or thought better fits each person. Each photograph consists of a picture of the eye region with four words in each of its corners which describe feelings and/or thoughts. The total score, which ranges from 0 to 36 points, is obtained by adding up the number of correct answers (Baron-Cohen et al., 2001), with a higher score indicating stronger emotion decoding abilities. Cronbach alpha for this study was .60, which is in line with previous studies in this field (Oakley et al., 2016; Romero-Martínez, Lila, et al., 2022).

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (Saunders et al., 1993)

For measuring alcohol abuse we employed the Spanish version (Contell-Guillamón et al., 1999) of the to check for the quantity and frequency of alcohol use in adults. This test contains 10 self-report items ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (daily or almost daily), obtaining a maximum score of 40. Internal consistency of the test in this study was good, α = .84.

Severity Dependence Scale

We modified the Spanish version to assess cannabis and cocaine misuse, conveniently adapting it to each drug (Miele et al., 2000; Vélez-Moreno et al., 2013). This test contains 5 items, each ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (always). A higher score is interpreted as high risk of presenting a substance use disorder. Cronbach's alpha for both scales were above .88.

Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2) (Muñoz-Rivas et al., 2007; Straus et al., 1996)

The Spanish version of this scale was employed to assess how individuals tend to solve their relationship conflicts (e.g., negotiation, sexual coercion, physical abuse, etc.). Participants report on their own behaviors and those of their partners during conflicts. The measure consists of 78 items rated on an 8-point Likert-type scale, where 0 represents this has never happened and 6 represents more than 20 times in the past year; however, 7 represents not in the past year, but it has happened before. Cronbach's alphas for the present study were above .70.

Plutchik Scale (Plutchik and Van Praag, 1989)

The Spanish adaptation (Rubio-Valladolid et al., 1999) was used to assess impulsivity. This questionnaire consists of 15 items, with a response scale of 4 points (from 0, never, to 3, almost always). A total score was obtained with the sum of all the items, considering that some of them are inverse, with a higher score being interpreted as greater impulsiveness. For this study we considered a cut-off score of 20. Confidence for this study was .70.

For assessing dropout (or treatment compliance) participants were dummy coded as completers (0) if they finished the intervention, or dropout (1) if they left the intervention before it ended.

To assess official recidivism, we employed the VioGen database, which is the monitoring system of the Spanish Ministry of the Interior. Specifically, IPV perpetrators were coded with 0 (if the participant did not reoffend) and 1 (if he reoffended).

Data Analysis Plan

After checking for group differences in age and demographic variables, we conducted one-way ANOVAs and chi-square analyses depending on the nature of these variables. The variables which differ between groups were then included as covariates in posterior analysis.

For assessing the first objective of the study, we initially checked for normal distribution of neuropsychological performance, log transforming those variables which did not adjust to normal distribution. Furthermore, analyses employing ANCOVAs including ‘group', ‘alcohol and drug misuse' as covariates were repeated.

With regard to the second objective, logistic regression analyses for assessing the effect of ‘group' in dropout and official recidivism were applied. Afterwards, chi-square analyses were employed as post hoc.

Regarding the third objective of this study, after calculating Pearson or Spearman correlation analyses, logistic regressions with those neuropsychological variables which were significantly associated with dropout and official recidivism, including ‘group', ‘alcohol and drug misuse' as covariates, were conducted. Last, a moderation analysis was conducted, as recommended by Preacher et al. (2007). Specifically, we employed PROCESS v3.5, including the neuropsychological variable as the independent variable, dropout, and official recidivism as dependent variables, and group as potential moderating variable.

Data analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 26.0 (Armonk, NY, USA). P values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

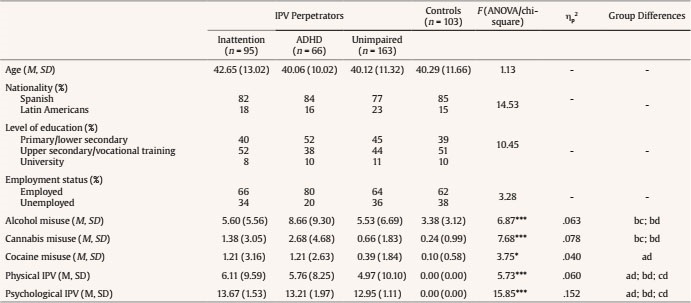

As can be seen in Table 1, we checked for differences in age, demographic variables, alcohol, and drug misuse between groups. Even though there were no differences in any of the variables considered, that is, age, number of children, educational level, nationality, and/or working status, groups differed in terms of alcohol, drug misuse, and physical and psychological IPV perpetration. Thus, alcohol and drug misuse were considered in a later analysis to control their potential role.

Table 1. Means, Standard Deviations, Percentages, and Means Comparisons for Socio-Demographic and Psychological Variables for All Groups.

Note.ADHD = attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; IPV = intimate partner violence; group differences = a (inattention IPV perpetrators), b (ADHD IPV perpetrators), c (unimpaired IPV perpetrators), d (controls).

*p < .05,

***p < .001.

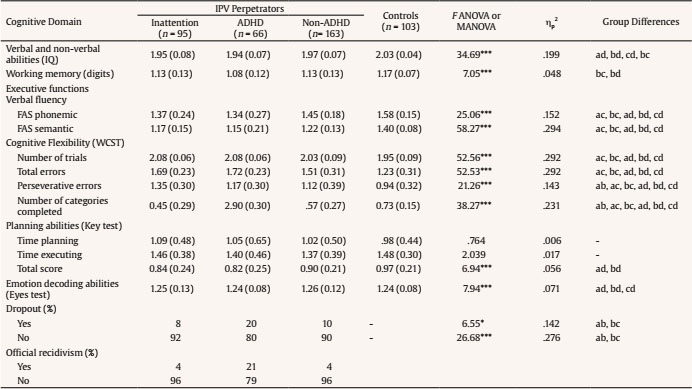

Neuropsychological Performance

Regarding verbal and non-verbal abilities (IQ), a group effect was found, F(3, 425) = 34.69, p < .001, ηp2 = .199, with all groups of IPV perpetrators (inattention, ADHD and unimpaired) presenting lower performance than controls (t = -0.083, p < .001, d = 1.26; t = -0.091, p < .001, d = 1.58; and t = -0.064, p < .001, d = 1.18, respectively). ADHD IPV perpetrators also presented lower verbal and non-verbal abilities than unimpaired IPV perpetrators (t = -0.031, p = .011, d = 0.46). After including alcohol and drug misuse, the ‘group' effect remained significant, F(3, 425) = 10.83, p < .001, ηp2 = .110 (Table 2).

Table 2. Means, Standard Deviations, and Mean Comparisons for Neuropsychological Variables and Percentages of Dropout and Official Recidivism for All IPVAW and Controls.

Note.IPV = intimate partner violence; WCST = Wisconsin Card Sorting Test. Group differences: a (inattention IPV perpetrators); b (ADHD IPV perpetrators); c (unimpaired IPV perpetrators); d (controls).

*p < .05,

***p < .001.

With regard to working memory performance, group differences significantly emerged in digit span, F(3, 425) = 7.05, p < .001, ηp2 = .048. Post hoc analyses revealed that ADHD participants obtained worse performance than unimpaired IPV perpetrators and controls (t = -0.048, p = .036, d = 0.42 and t = -0.085, p < .001, d = 0.92, respectively). After including alcohol and drug misuse, the ‘group' effect was still significant, F(3, 425) = 2.76, p = .043, ηp2 = .030 (Table 2).

Regarding executive functioning, we initially checked differences in the verbal fluency between groups of IPV perpetrators and controls. Several significant differences were observed in verbal fluency (phonemic), F(3, 425) = 25.06, p < .001, ηp2 = .152, and semantic, F(3, 425) = 58.27, p < .001, ηp2 = .294. The post-hoc analysis revealed that all groups of IPV perpetrators (inattention, with ADHD and unimpaired) presented worse performance than controls in phonemic (t = -0.21, p < .001, d = 1.04; t = -0.25, p < .001, d = 1.09; and t = -0.13, p < .001, d = 0.78, respectively) and semantic (t = -0.23, p < .001, d = 1.91; t = 0.25, p < .001, d = 1.57; and t = 0.18, p < .001, d = 1.58, respectively). Furthermore, differences were found between ADHD IPV perpetrators and those with inattention compared to unimpaired IPV perpetrators in phonemic (t = -0.12, p = .001, d = 0.52 and t = -0.07, p = .028, d = 0.38, respectively), but only between ADHD IPV perpetrators and unimpaired IPV perpetrators in semantic (t = -0.07, p = .005, d = 0.39). After including alcohol and drug misuse, group differences remain significant for phonemic, F(3, 425) = 13.53, p < .001, ηp2 = .133, and semantic performance, F(3, 425) = 30.91, p < .001, ηp2 = .261 (Table 2).

With regard to the cognitive flexibility measure (WCST), specifically the number of trials, F(3, 425) = 52.56, p < .001, ηp2 = .292, total errors, F(3, 425) = 52.53, p < .001, ηp2 = .292, perseverative errors, F(3, 425) = 21.63, p < .001, ηp2 = .143, and completed categories, F(3, 425) = 38.27, p < .001, ηp2 = .231, the post-hoc analysis revealed that all groups of IPV perpetrators (inattention deficits, with ADHD and unimpaired) needed more trials (t = 0.14, p < .001, d = 1.70; t = 0.14, p < .001, d = 1.70; and t = 0.09, p < .001, d = 0.89, and respectively), made more total errors (t = 0.46, p < .001, d = 1.76; t = 0.28, p < .001, d = 0.95; and t = 0.49, p < .001, d = 1.90, respectively), perseverative errors (t = 0.41, p < .001, d = 1.35; t = 0.17, p < .001, d = 2.39; and t = 0.24, p < .001, d = 0.79, respectively), and completed less categories than controls (t = 0.28, p < .001, d = 1.26; t = 0.43, p < .001, d = 1.86; and t = 0.16, p < .001, d = 0.73, respectively). Unimpaired IPV perpetrators needed less trials (t = -0.05, p < .001, d = 0.65 and t = -0.05, p = .001, d = 1.26, respectively), made fewer errors (t = -0.18, p < .001, d = 0.66 and t = -0.21, p < .001, d = 0.77, respectively), perseverative errors (t = -0.23, p < .001, d = 0.17), and completed more categories (t = 0.12, p < .001, d = 0.47 and t = 0.28, p < .001, d = 0.98, respectively) than IPV perpetrators with inattention and those with ADHD, except for perseverative errors in which only differences between unimpaired IPV perpetrators and those with ADHD were found. Finally, IPV perpetrators with inattention completed less categories than those with ADHD (t = -0.16, p = .004, d = 0.54). After including covariates, differences between groups still reached significance for the number of trials, F(3, 425) = 24.65, p < .001, ηp2 = .231, total errors, F(3, 425) = 26.04, p < .001, ηp2 = .241], perseverative errors, F(3, 425) = 10.40, p < .001, ηp2 = .113, and completed categories, F(3, 425) = 12.38, p < .001, ηp2 = .135 (Table 2).

The assessment of planning abilities revealed that the groups differed on total score, F(3, 425) = 6.94, p < .001, ηp2 = .056, with IPV perpetrators with inattention and those with ADHD presenting lower scores than controls (t = -.13, p = .002, d = 0.58 and t = -0.15, p = .001, d = 0.56, respectively). After including covariates, the ‘group' effect still remained significant, F(3, 425) = 4.21, p = .006, ηp2 = .055 (Table 2).

Regarding emotion decoding (eyes test), a significant group effect was found, F(2, 425) = 7.94, p < .001, ηp2 = .071, with all groups of IPV perpetrators (without ADHD, with inattention deficits and with ADHD) presenting lower scores than controls (t = 0.09, p < .001, d = 1.01; t = 0.09, p < .001, d = 1.29; and t = 0.08, p < .001, d = .81, respectively). After including covariates, differences between groups still reached significance, F(2, 425) = 9.44, p < .001, ηp2 = .102 (Table 2).

Group Differences in Dropout and Official Recidivism

A significant effect for ‘group' was found for dropout, Wald(1) = 4.19, SE = 0.14, p = .041; Exp(β) = 1.34; 95% CI [1.01, 1.76], with the group effect remaining significant after including alcohol and drug misuse as covariates, Wald(1) = 9.61, SE = 0.18, p = .002, Exp(β) = 1.75, 95% CI [1.23, 2.49]. The post hoc analysis revealed that a higher percentage of ADHD IPV perpetrators (20%) abandoned the treatment before its end compared to those with inattention (8%) or unimpaired (10%,) χ2(1) = 5.44, p = .020, Vcramer = .184 and χ2(1) = 4.15, p = .042, Vcramer = .135, respectively (Table 2).

With regard to official recidivism, a significant ‘group' effect was also found, Wald(1) = 8.01, SE = 0.14, p = .005, Exp(β) = 1.49, 95% CI [1.13, 1.97], remaining significant after including covariates, Wald(1) = 7.91, SE = 0.16, p = .005, Exp(β) = 1.58, 95% CI [1.15, 2.18]. The post hoc analysis revealed that a higher percentage of ADHD IPV perpetrators (21%) reoffended in comparison with those IPV perpetrators with inattention (4%) and those unimpaired (4%), χ2(1) = 11.34, p = .001, Vcramer = .265 and χ2(1) = 18.11, p < .001, Vcramer = .281, respectively (Table 2).

Neuropsychological Performance of IPV Perpetrators as Predictors of Dropout and Official Recidivism

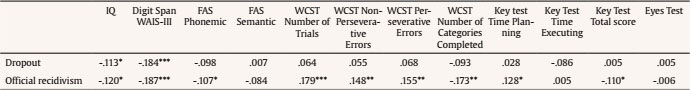

After conducting a correlational analysis (Table 3), several logistic regressions were conducted to assess whether those neuropsychological variables significantly related to dropout and official recidivism still explain those variables after including ‘alcohol and drug misuse' as covariates.

Table 3. Correlations of Neuropsychological Variables with Dropout, and Official Recidivism for the IPV Perpetrators.

Note.IPV = intimate partner violence; IQ = intelligence quotient; WCST = Wisconsin Card Sorting Test.

*p < .05,

**p < .01,

***p < .001.

With regard to dropout, IQ, Wald(1) = 4.43, SE = 2.57, p = .035, Exp(β) = .005, 95% CI = .00 to .69), and digit span, Wald(1) = 11.71, SE = 1.51, p = .001, Exp(β) = .006, 95% CI [.00, .11], still predict dropout.

For official recidivism, we also found a significant main effect of IQ after including covariates, Wald(1) = 5.99, SE = 2.72, p = .014, Exp(β) = .001, 95% CI [.00, .27]. This was similar for digit span after including covariates, Wald(1) = 5.71, SE = 1.56, p = .017, Exp(β) = .02, 95% CI [.001, .51). The WCST non-perseverative errors, Wald(1) = 5.13, SE = 1.12, p = .024, Exp(β) = 12.59, 95% CI [1.41, 112.65], the number of categories completed, Wald(1) = 8.83, SE = .87, p = .003, Exp(β)= .075, 95% CI [01, .42], and key test time planning, Wald(1) = 4.17, SE = .54, p = .041, Exp(β)= 3.03, 95% CI [1.05, 8.78], also remained significant after including covariates.

Moderation Role of ‘Group' between Neuropsychological Performance and Dropout and Official Recidivism

After conducting moderation models, the interaction between IQ and digit span and group did not increase the amount of explained variance of dropout (McFadden = .11, coeff = -3.73, SE = 2.75, Z = -1.36, p = .18, and McFadden = .15, coeff = -.67, SE = 1.33, Z = -0.50, p = .62; respectively).

Regarding official recidivism, the interaction between group with IQ did not increase the amount of explained variance of official recidivism (McFadden = .14, coeff = -3.47, SE = 2.46, Z = -1.41, p =.16). The interaction between group digit span (McFadden = .13, coeff = -1.33, SE = 1.31, Z = -1.02, p = .31), WCST non-perseverative errors (McFadden = .17, coeff = .30, SE = .68, Z = 0.44, p = .66), number of categories completed (McFadden = .17, coeff = -.66, SE = .65, Z = -1.02, p = 31), and key test time planning (McFadden = .20, coeff = -.09, SE = .38, Z = 0.23, p = .82) also failed to reach significance for predicting official recidivism. Therefore, ‘group' did not moderate the association between neuropsychological functioning and dropout and/or official recidivism.

Discussion

The main three objectives of our study were: 1) to find out whether IPV perpetrators with and without ADHD differed among themselves and compared to non-violent men in several cognitive domains evaluated by neuropsychological tests, 2) whether there were differences between IPV perpetrators (with and without ADHD) relative to dropout (treatment compliance) and official recidivism and, most importantly, 3) if the ADHD diagnosis and neuropsychological performance interact to predict dropout and official recidivism among IPV perpetrators.

Our results indicate that all the groups of IPV perpetrators (with and without ADHD) presented worse performance in all cognitive domains assessed (i.e., IQ, working memory, verbal fluency, cognitive flexibility, planning abilities, and emotion decoding abilities) than controls. Additionally, ADHD IPV perpetrators presented worse performance in all cognitive domains than unimpaired IPV perpetrators, but not in comparison with inattention IPV perpetrators. Additionally, IPV perpetrators affected by ADHD presented the highest rate of dropout and official recidivism. Lastly, even though neuropsychological impairments and IPV perpetrators' group variables separately significantly explained dropout and official recidivism, their interaction did not increase the amount of explained variance and, therefore, were not significant to predict each one. All these results remained significant after controlling the effect of drug misuse.

We initially hypothesized that ADHD IPV perpetrators (combined subtype) would present worse performance compared to unimpaired IPV perpetrators and controls, but not among subtypes of ADHD groups, which was in line with previous research in this field (Loyer-Carbonneau et al., 2021; Pievsky & McGrath, 2018). Sure enough, our data pointed out that IPV perpetrators with ADHD combined subtype presented neuropsychological differences in all cognitive domains in comparison with unimpaired IPV perpetrators and controls, planning abilities and emotion decoding abilities compared to unimpaired IPV perpetrators. Moreover, it was particularly interesting that only a group of IPV perpetrators, specifically ADHD IPV perpetrators, presented worse working memory performance compared to unimpaired IPV perpetrators and controls. Our data also reinforced that all groups of IPV perpetrators presented worse neuropsychological performance than controls, as it has been previously stated (Babcock et al., 2008; Cohen et al., 2003; Easton et al., 2008; Romero-Martínez, Lila, et al., 2022; Walling et al., 2012), with the effect size of these differences being moderate or large, specifically, for verbal fluency and cognitive flexibility, and low for the rest of the variables. Therefore, IPV perpetrators' performance could not be considered as a deficit (1.5-2 SD below performance of control group), situating their performance slightly below the control group. A priori, those neuropsychological differences could be attributed to different patterns of alcohol and/or drug misuse acting as confounding factors. In fact, the presence of a substance use disorder might be masking the performance of individuals affected by ADHD (Slobodin, 2020). Curiously all these differences remained significant after controlling their effect. Thus, we could consider both factors as complementary risk factors instead of drugs developing a moderator role between ADHD and IPV, as their inclusion in statistical analysis increased the amount of explained variance without affecting the significant effect of group above neuropsychological performance.

Results of the rate of dropout and recidivism among IPV perpetrators with different severity of ADHD symptoms were in line with conclusions proposed by Wymbs et al. (2017) but contrasted with those obtained by the same authors (Wymbs et al., 2019; Wymbs et al., 2015). That is, our study highlighted that ADHD (combined subtype) presented the highest rate of dropout and recidivism, even after controlling the effect of alcohol and drug misuse. Hence, as stated above, alcohol and drug misuse should be considered a relatively independent factor in the association between ADHD and IPV perpetration. In any case, we need to keep in mind that we assessed two final intervention outcomes (e.g., dropout and official recidivism) instead of IPV levels. Furthermore, we considered a sample of adults convicted of IPV, whose drug misuse levels tend to be higher than normative population (Hines & McDouglas, 2012), instead of young normative adults without IPV conviction as Wymbs et al. (2015), Wymbs et al. (2017), and Wymbs et al. (2019) did before. Given that we cannot attribute violence proneness in ADHD individuals to drug misuse, our data highlighted the need to incorporate or develop coadjutant intervention strategies focused on ADHD symptoms differentiated from others, paying attention to substance use disorders, although this does not mean or contradict that certain individuals need both intervention strategies together to reduce dropout and recidivism by attending to individual needs.

The main novelty of this research was the results related to the third objective, to measure whether neuropsychological performance joined with the ADHD diagnosis to explain dropout and official recidivism. We hypothesized that ADHD, particularly combined subtype, with the highest neuropsychological deficits would explain IPV perpetrators' dropout, as well as official recidivism. Contrary to our expectations, the inclusion of both factors increased the amount of explained variance, but the interaction between both did not reach significance for explaining the above-mentioned dependent variables. Thus, as stated before, we cannot consider that the neuropsychological deficits mediate and/or moderate the association between ADHD symptoms and dropout and official recidivism for all the IPV perpetrators with combined or inattention subtypes, being, hence, both risk factors relatively independent. Thus, these factors should be treated independently (e.g., pharmacological + cognitive training).

Working memory functioning explained dropout, whereas IQ, working memory, and cognitive flexibility significantly explained official recidivism. To understand the reduced rate of treatment compliance, we can speculate that ADHD IPV perpetrators might feel overwhelmed by the content of intervention programs, as they did not have the appropriate cognitive skills to deal with a complex content such as interrogating their own feelings, changing hostile cognitive schemas regarding women, improving decision-making processes, etc. In this sense, working memory processes sustain other more complex processes for making and planning decisions. This, in turn, might considerably increase the risk of recidivism, given that they do not change certain hostile cognitive schemas or behavioral regulation, among others, to deal appropriately with certain conflictive and demanding context.

Our study highlights the need for complementing current standard batterer programs with cognitive training attending to IPV perpetrators' cognitive needs in order to decrease the risk of dropout and official recidivism. In this sense, there is an example of a randomized controlled pilot study, which compared a standard intervention with another group of IPV perpetrators receiving this program in combination with cognitive training (e.g., including pen and pencil tasks and videos, among others). This last group experienced considerable improvements in several cognitive domains, such as speed processing and cognitive flexibility, as well as a considerable reduction in the risk of reoffending (Romero-Martínez, Santirso, et al., 2022). Cognitive training has also been concluded to present a certain, although limited, positive impact by reducing working memory and executive functioning deficits in people affected by ADHD, which also has an impact on reducing the severity of ADHD behavioral dysregulation (Cortese et al., 2015). Hence, an initial neuropsychological assessment to identify cognitive needs and other neurological diagnosis and, consequently, implementing coadjutant intervention programs should be incorporated.

The present study had several strengths and offer an interesting perspective of IPV, but there were also several limitations which should be kept in mind for conducting future research. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study design and the relatively reduced sample limited the causality of the associations between the variables. Thus, it would be necessary to replicate the results in future studies with a longitudinal study and a larger sample size. Second, we would like to point out that it would be suitable for future studies to measure temporal stability of ADHD diagnosis. Furthermore, it would be important to take into account previous ADHD diagnosis from other mental health professionals or whether participants were diagnosed during their childhood or adolescence. Particularly, whether IPV perpetrators experience notorious changes in several cognitive abilities after intervention. Furthermore, it would be important to include other ADHD screening tools during the initial assessment of IPV perpetrators to further complement the diagnosis by facilitators. In fact, the role of CPT-3 performance to clearly differentiate ADHD from other disorder diagnosis, such as reading disorders or dyslexia, has been criticized (McGee et al., 2000; Miranda et al., 2012). Third, it would be important to consider a larger number of neuropsychological tests to determine whether IPV perpetrator typologies clearly differ in their cognitive profiles (e.g., decision-making, inhibitory control, planning abilities with more complex tests, etc.). In this sense, we would like to highlight the need for developing new instruments for assessing emotion decoding abilities, as the Eyes Test showed poor internal consistency, but in line with what is indicated in a systematic review (Oakley et al., 2016). It is important to bear in mind that this low internal consistency reduces the value for conclusions. Four, participants were codified as reoffenders and non-reoffenders, but this did not offer too much information regarding the type of re-offense (e.g., physical, psychological violence, violation of a restraining order, etc.). This would help in future studies for a wider understanding of reoffending/recidivism. Five, it would be important to include other groups of IPV perpetrators (e.g., ADHD impulsive subtype) and/or controls affected by ADHD but without IPV conviction for contrasting and complementing current results. Furthermore, we considered it particularly important to assess how neuropsychological performance of IPV perpetrators would be associated with different strategies when coping with couple arguments in future research.

In conclusion, our data underline the importance of ADHD, especially the combined subtype, and the neuropsychological deficits for explaining dropout and official recidivism in IPV perpetrators, independently of alcohol and drug misuse. Moreover, we support the need for developing coadjutant cognitive training programs for neuropsychological dysfunctions and treatment for ADHD symptoms, which clearly interfere with current adherence to intervention programs for IPV perpetrators and recidivism. In addition, we do not reject incorporating other alternatives such as pharmacological strategies and non-invasive brain techniques, when necessary, which could increase the success of current interventions because they make it possible to increase the success of psychological interventions. Thus, future research in this field should consider all these variables, which will allow us to build a biopsychosocial model of treatment compliance and recidivism.