INTRODUCTION

Advances in early diagnosis and comprehensive treatment of cystic fibrosis (CF) have caused an increase in the survival of these patients 1. One of the factors that has contributed to this phenomenon has been the improvement of the nutritional status through intensive nutritional intervention based on hypercaloric diets and nutritional supplements, as well as enteral nutrition and pancreatic enzymes for the control of steatorrhea.

On the other hand, patients with CF are not free from the prevailing sedentariness in our current society, which, combined to the improvements in medical and nutritional treatment, has led to the existence of a potential risk for excessive weight gain in some of these patients.

There are few data regarding the actual prevalence of overweight in CF. Recently published studies in Toronto and the USA indicate a prevalence of overweight between 15 and 18% (in children and adults respectively) and up to 8% for obesity 2) (3.

Obesity is widely recognized as an important risk factor for the development of metabolic complications such as insulin resistance, hypertension, and dyslipidemia, which may increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes. However, the presence of these obesity-related metabolic disturbances varies widely among obese individuals. Accordingly, a unique subset of obese individuals has been described in the medical literature that appears to be protected or more resistant to the development of metabolic abnormalities associated with obesity. These individuals, now known as "metabolically healthy but obese", despite having excessive body fatness, display a favorable metabolic profile characterized by high levels of insulin sensitivity, no hypertension, as well as normal lipid, inflammation, hormonal and immune profiles 4.

In contrast to the general population, CF patients who are overweight or obese have good pulmonary function 5. However, recent studies suggest that after certain thresholds, body mass index (BMI) is inversely correlated with pulmonary function 6. On the other hand, the effects of excess weight at the cardiovascular level are unknown in this population. For CF patients, absolute BMI should be maintained at or above 22 kg/m2 in females and 23 kg/m2 in males. For children, the 50th percentile is optimal 7.

The objective of our study was to establish the prevalence of overweight and obese status, as well as its association with pulmonary function, vitamin D and total cholesterol in our population of CF patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a multicenter descriptive and cross-sectional study that was done from November 1st 2012 to April 30th 2014 during the months of November to April (when vitamin D levels were at nadirs). Clinically stable CF patients over four years old, in absence of pulmonary exacerbation, in 12 Spanish university hospitals were enrolled. Ethical approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Principality of Asturias, reference number (no. 45/15). Patients and guardians received written, complete and detailed information of the study, and all of them signed their informed consent for the study. All patients were treated according to published European CF guidelines 8.

Each patient was identified with a code assigned to the hospital and the case. Information was taken from the patients' medical files.

The date of birth, gender, race, the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene genetic test, as well as whether they had been diagnosed using neonatal screening, were also recorded.

The investigators measured the morning weight and height, patients being barefoot and in underwear, using instruments with a precision of 50 g and 0.5 cm respectively, and calculated BMI. All somatometric data were classified (z-score) according to the WHO references 9. The nutritional status of each patient was classified according to the BMI in adults (≥ 18 years old) and the BMI percentile in children, as follows: malnourished (< 18.5 kg/m2, < P10), nutritional risk (18.5-21.9 kg/m2 for female, 18.5-22.9 for male kg/m2; P10-p49), normally nourished (22-24.9 kg/m2 for female, 23-24.9 kg/m2 for male; P50-84), overweight (25-29.9 kg/m2, P85-94) and obese (≥ 30 kg/m2, ≥ P95). Those with growth failure were also considered as malnourished (height < P3) 8)(10.

Pancreatic function was established with the determination of fecal elastase-1 (E-1) levels. Information was taken from the medical file of the patients. Those with concentrations less than 200 μg/g were considered to have pancreatic insufficiency (PI) 11.

The daily dose of vitamin D received by patients was quantified in IU/day. Vitamin D levels in the form of serum 25 OH vitamin D were measured by chemiluminescence immunoassays (CLIA) in each hospital. Levels of 25 OH vitamin D less than 30 ng/ml and 20 ng/ml were considered to be insufficient and as deficiency, respectively 12. Total cholesterol levels were quantified in mg/dl form and hypercholesterolemia was considered when levels were above 200 mg/dl. The measurements were taken while fasting.

Pulmonary function was analyzed as the forced expiratory volume in the first second of expiration (FEV1) using forced spirometry. Percentages were calculated from the absolute values expected for healthy individuals with the same age, gender and height as the patient 13.

The data collected were exported to a statistical data management program (STATA version 13.0). Basic statistical techniques for descriptive analysis were applied for the study. Pearson and Spearman correlation tests were used to analyze the joint behavior of the quantitative variables. Two-tailed t-tests were used for comparison of the averages of two groups, as well as one-factor ANOVA and Bonferroni post-hoc tests for comparison of the averages of three or more groups. For comparison of proportions, Chi-squared tests were used. To analyze the association between nutritional status, FEV1, cholesterol and 25 OH vitamin D, a linear regression analysis was conducted with multivariate adjustment (by sex, age, PI, CFTR gene, screening). If some of the variables did not meet some of the requirements of normality, non-parametric tests were applied (Mann-Whitney test). The differences were considered as statistically significant when the probability value was p < 0.05.

RESULTS

DESCRIPTIVE CHARACTERISTICS

A total of 451 patients with CF aged 4-57 years old (median age [Md] 12.3 years old) were included in this study. Table I shows the main anthropometric characteristics and data of the 451 patients analyzed.

NUTRITIONAL STATUS

When analyzing the nutritional status of our patients according to BMI and height, 12% were malnourished, 57% were at nutritional risk, 24% were normally nourished, 6% were overweight and 1% were obese. If we use BMI as the only nutritional criterion, two of the patients classified as normally nourished (0.5%) and 14 of the patients classified as being at nutritional risk (3%) must be classified as malnourished given that their height was less than P3.

Patients who were overweight or obese (excess weight group) were between five and 49 years old, with a Md of 12 and an interquartile range (IQR) between ten and 16 years. Twenty-seven per cent were homozygous carriers of the DF508 mutation, 43% were heterozygous carriers and 30% were not carriers of said mutation on any of their alleles. Fifty-two per cent were males. The age, gender distribution and genetic background of the patients who were overweight or obese were similar to those of the rest of the sample. A greater proportion of pancreatic sufficient (PS) was observed, 55% vs 15% (p < 0.001), as well as a lower proportion of patients receiving vitamin D supplements, 76% vs 93% (p < 0.001).

Regarding vitamin D, 8% of patients, all of them pancreatic sufficient, did not receive daily supplementation. In those who received it, the median dose was 962 IU/day of vitamin D (IQR 800-1,600 IU/day).

NUTRITIONAL STATUS AND PULMONARY FUNCTION

In pediatric patients, an association was observed between BMI (z score) and FEV1 (%) (r = 0.250, p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Pulmonary function in patients who were excess weight (overweight or obese) (91 ± 19%) was better than in malnourished patients (77 ± 24%) (p = 0.017). However, differences were not observed between excess weight and those who were at nutritional risk (86 ± 19%) or normally nourished (90 ± 22%) (Fig. 2).

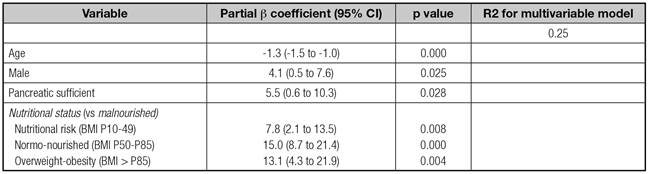

The association between nutritional status and FEV1 was analyzed using a linear regression analysis. The variables that were kept in the model were: male gender; age; PS and malnutrition (Table II).

TOTAL CHOLESTEROL AND VITAMIN D IN OVERWEIGHT CF PATIENTS

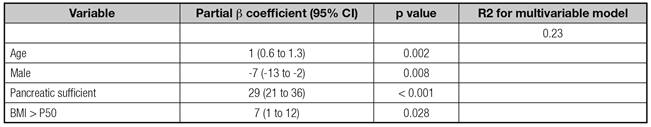

Levels of total cholesterol were between 58 and 265 mg/dl, with a Md of 130 mg/dl (IQR 111-152.5 mg/dl). Only 5% of the patients had levels of total cholesterol above 200 mg/dl. Thirty-three per cent of obese patients had hypercholesterolemia; Md cholesterol in this group was 169 mg/dl (IQR 153-228 mg/dl). The proportion of hypercholesterolemia was greater in adult patients 11% vs 3% (p = 0.003). Patients who were excess weight compared with non-overweight neither obese had elevated levels of total cholesterol: 154 ± 8 vs 130 ± 1 mg/dl (p = 0.0049) and a greater proportion of hypercholesterolemia 16% vs 3% (p = 0.001). However, those associations were not maintained in the multivariate analysis (Table III).

Table III Results of multivariable linear regression for associations of subject characteristics with total cholesterol

Levels of vitamin D were between five and 95 ng/ml with a Md of 26 ng/ml (IQR 20-33.5 ng/ml). Sixty-four per cent had insufficient levels, and 25% of these had levels lower than 20 ng/ml. In obese, the Md was 23 ng/ml (IQR 22-25 ng/ml). The patients who were excess weight compared with non-overweight neither obese had lower levels of vitamin D (24 ± 2 vs 28 ± 1) ng/ml (p = 0.058). Adjusting for confounding factors and modifiers such as age, exocrine pancreatic function and vitamin D dose received, the patients who were overweight maintained lower levels of 25 OH vitamin D but it was not statistically significant: b = -5.28 (CI 95% -10.51 and 0.09) (p = 0.054) ng/ml.

DISCUSSION

Obesity and weight gain have become a genuine epidemic, whose prevalence has doubled in developed countries in the last 20 years. In Spain, 30% of children between six and 12 years old are overweight, and 10% are obese 14. The phenomenon is primarily related to exogenous causes, such as an increase in energy consumed in the diet, combined with a reduction in the activities that involve energy expenditure and an increase in those of the sedentary type, and it is also associated with genetic and epigenetic factors. This tendency in lifestyle is not exclusive to the general population. It also affects patients with chronic diseases such as CF, probably with greater intensity.

In our study we observed that 7% of patients carried excess weight (6% overweight and 1% obese), about half the number of malnourished patients (12%), while the majority presented normal nutritional status. If we keep in mind the physiopathology of this disease, this prevalence seems to be elevated; however, our numbers are lower when we compare them to North American data, where prevalence reaches 23% (15% overweight and 8% obese) 3. These results could be explained by the differences in lifestyle and diet between both countries. There are also methodological differences between the two analyses: in contrast to our study, the North American series only uses body mass index, without accounting for growth failure as a malnutrition criteria. Consequently, patients who are actually malnourished could be categorized incorrectly as normally nourished or overweight. Another important factor could be age, excess weight is mostly described in adults CF patients with mild phenotypes and SP.

Advances in the genetic knowledge of this disease and the implementation of neonatal screening have allowed more frequent diagnosis of patients with less aggressive phenotypes and PS. In our study, the proportion of patients with PS was greater in those who were overweight or obese (> 50%), a fact already described by Stephenson et al. 2 in a longitudinal study in adults with CF, wherein overweight status is associated with PS, advanced age, good pulmonary function and male gender. These PI patients have energy requirements that are similar to those of the general population; however, the majority of guides do not make distinctions, and specific nutritional recommendations do not exist for these types of patients. However, excess weight is not exclusively associated to milder clinical forms. In our case, more than 25% of patients who were overweight or obese were homozygous carriers of the DF508 mutation and presented exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI). This circumstance was previously described by Kastner-Cole 5 in a study conducted on 3,000 pediatric and adult patients who were homozygous carriers of the DF508 mutation, in which up to 9% were observed to be overweight and 1% obese.

The positive association between nutritional status and pulmonary function is well-known in this disease. Additionally, in contrast to the general population, patients who are overweight and obese have good pulmonary function. In our analyses, we observe a positive association between BMI and FEV1, as well as the negative effect of malnutrition on pulmonary function. However, the patients who were overweight and obese did not have better pulmonary function than those who were normally nourished or at nutritional risk. Moreover, in the multivariate analysis we observed how, in those who maintained a BMI between P50 and P85, this had a superior effect on pulmonary function compared to those who were overweight or obese. Recent publications in adults suggest that the positive association between BMI and FEV1 is reversed from BMI values > 25 kg/m2 (2) (6. On the other hand, it has been observed that the parameter best associated with pulmonary function, from the nutritional point of view in these patients, is the fat-free mass index 15) (16. However, given the difficulties in accessing the body composition tests, we consider that the use of BMI between P50 and P85 as a nutritional objective can be helpful in usual clinical practice.

The association between overweight and obese status and vitamin D deficiency has been described in the general population. The mechanism is not exactly known, but it is believed that it is due to the decrease in the bioavailability of vitamin D secondary to the increase in adiposity of obese patients 17. To our knowledge, to date vitamin D levels have not been analyzed in patients with CF and overweight or obese status. In our study we observe how, independently of factors that affect levels of vitamin D in this disease, such as exocrine pancreatic function, age, dose of vitamin D, and chronic inflammation (all were in absence of pulmonary exacerbation), patients with excess weight had an average of 5 ng/ml less of 25 OH vitamin D (p = 0.054). Given the increase in the prevalence of overweight status in this disease, we consider that this is another factor that should be kept in mind when the serum levels of this fat-soluble vitamin are analyzed.

Cholesterol levels in patients with CF are generally lower compared to the general population. In our study, only 5% had hypercholesterolemia, with endocrine pancreatic function being the variable that best determined levels of cholesterol, in such a way that PS patients had between 21 and 36 mg/dl more total cholesterol than PI patients. These differences are explained primarily because patients with PI, even when receiving enzyme supplementation, present fat malabsorption as well as greater chronic inflammation. The atherogenic lipid profile characterized by elevation of LDL cholesterol and the total cholesterol/HDL ratio has been observed in 50% of PS adult patients and up to 24% of IP patients 18. An association between BMI and LDL cholesterol in adult CF patients was recently described 19. Even though data on the HDL and LDL cholesterol fractions is not available, hypercholesterolemia values are above those published in our study, probably due to the lower age of our patients.

Microvascular complications have been described in patients who presented cystic fibrosis-related diabetes 20. However, only isolated published cases of macrovascular complications in adults with CF are known 21. Even when receiving a hypercaloric diet 22, the apparent absence of atherosclerosis is explained by the low levels of cholesterol as well as by the difficulty patients have surviving into the 5th and 6th decade of life, the age at which peak incidence of these diseases occurs in the general population. However, the increase in life expectancy, as well as overweight and obese status, and the presence of more atherogenic lipid profiles in patients with PS, must alert us to the risk of developing metabolic problems not described to date in patients with CF.

Our study is one of the broadest published to date that analyses the prevalence of overweight and obese status in pediatric and adult patients with CF, as well as the first to analyze the association between vitamin D and excess weight in these patients. Despite the results, we are conscious of the methodological limitations of the study. The cross-sectional nature of this study does not allow us to conclude if the excess weight is the cause or the consequence. Nutritional evaluation with exclusively anthropometric data does not provide exact information on the real body composition of the patients; however, in contrast to other projects, we have included the evaluation of height to avoid under-diagnosing malnutrition. The multicentric nature, while necessary to obtain a sufficient sample size in a low prevalence disease such as CF, together with the retrospective collection of the data, may cause bias when analyzing serum levels and somatometric data, but close follow-up at specific units for this disease considerably reduces these errors. Another limitation was the small number of adults enrolled. Nowadays, half of patients of CF units are adults and up to one third are diagnosed at this age group, so the prevalence of overweight and obese as well as hypercholesterolemia may be increased in next years.

In summary, in the last few years we have observed an increase in nutritional problems due to excess weight in patients with CF. The benefits for pulmonary function, when compared to normally nourished patients, do not appear to be as significant as it was initially thought. Dietary recommendations based on hypercaloric diets must continue to be the basis of nutritional support, however, they must be personalized according to the characteristics of the patient. If we do not keep these circumstances in mind, in the near future we could face the appearance of metabolic problems not described to date in patients with CF.