INTRODUCTION

The recent economic and financial crisis has affected most Western countries, especially in families of low socioeconomic classes (LSC). Some reports have revealed a significant impact on the eating habits in children from families in poverty 1. UNICEF report on Spain in 2013 and others have found that families with children have suffered more intensively the economic restraints than the remainder of the population 2,3.

It was already well-known that, in industrialized countries, LSC are more likely to be obese than their high-socioeconomic group peers 4,5,6. Spain has one of the highest prevalence of excess of weight in children in school age across Europe: overweight prevalence 23.2% (22.4% in boys, 23.9% in girls) and obesity prevalence 18.1% (20.4% boys, 15.8% in girls) 7. Figures may slightly be modified according to the criteria used to define the excess of weight.

Contrary to what was expected by mass media, that is, an increase in undernourished children or children with nutritional deficiencies, our hypothesis was that worsening of socioeconomic condition associated with the crisis would increase obesity, mainly in disadvantaged families. A change in current feeding habits could be also expected.

In order to answer those questions, a cross-sectional study was designed to evaluate the nutritional status as well as the feeding patterns of school-aged children attending public schools in Madrid City. The study took place in the last trimester of 2014 and was study was carried out in collaboration with the local City Council.

METHODS

Cross-sectional study based on a questionnaire that was filled by parents/legal guardians of those children participating in the study.

SAMPLING SELECTION AND PROCEDURES

In Madrid City, 290,111 children, aged three to 12 years old, attended public school during the term 2014-2015. The study was done only in public schools as the local authorities are responsible of the functioning of those centers, and because of the feasibility of the study at those centers. A stratified weighted sample was randomly chosen, taking into account age (grade), city district and schools.

Thirty-two schools were selected, and two classes (3-5 years, Primary School; 6-12 years, Secondary School) of each center were included. After a meeting with the chief director of all schools explaining the project, the questionnaires were distributed by the teacher responsible of each class. Written informed consent was requested to parents or legal guardians prior to delivering the form.

In total, 1,211 filled questionnaires from 64 classes (32 schools) were retrieved. Three of them were incomplete and then excluded from the final analysis.

In order to obtain clearer information according to the main characteristics of the city, the centers were grouped in four areas: North, Central, Southwest and Southeast.

MEASUREMENTS

The questionnaire included weight and height (auto-reported) 8, dietary report (weekly frequency of intake), as well as socioeconomic variables (modified Family Affluence Scale [FAS] score 9: number of cars in the family, individual rooms at home, home away holidays in the last 12 months and number of computers at home; each item pointed 0-2). Families were classified according to previous questions as low socioeconomic status (0-3 points), middle socioeconomic status (4-5 points), and high socioeconomic status (6-7 points). Number of household members, country of origin, and employment status were also recorded.

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated based on the weight in kg and the height in meters reported by the participants. A child was considered to be undernourished when BMI Z-score was < -2, while they were considered to have excess of weight when BMI Z-score was > +1.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Categorical variables were summarized as relative frequencies (%) and range, while quantitative variables, as mean and standard deviations. Associations between categorical variables were assessed using the Chi-square test, as required. A p value < 0.05 was deemed statistically significant. All analyses were conducted with STAR for Windows 2.3.

RESULTS

In all, 1,208 questionnaires were evaluated. Half of participants were boys and half girls; 42% were younger than five years, 35% were between six and eight years, and 23% were older than eight. These figures were slightly different than the proportion of children according to age in data from the National Institute of Statistics (INE, 2014). Although most children were born in Spain (91%), their parents' nationality was 57% Spanish and 43% foreigners. Ecuador (19%), Morocco (14%) and Dominican Republic (11%) were the most frequent countries of origin. Forty three percent (43%) of families were composed by four members, and 22% were single-parent (in 93% the mother was the adult in charge). According to the origin, 46% of families with five or more members were from abroad, versus 23% in those of Spanish origin. According to the socioeconomic status, 34% had low, 41% had middle and 25%, high. Low socioeconomic status was more frequently present in families form non-Spanish origin, as well as in those living in the southern part of the city.

In 46% of the homes at least one of the parents was unemployed (40% in Spanish-origin families vs 54% in non-Spanish, p > 0.0001), and in 12% both parents were unemployed. Single-parent families reported "having trouble to make end of the month" in a higher percentage than the others (42% vs 32%, ns).

Nutritional status evaluation presented the following results: undernutrition was present in 5.0% of the sample, and excess of weight (overweight + obesity) in 36.7% (Fig. 1). Undernutrition was higher in children under the age of six (9.1%), with no differences between genders. We could not find any relationship between undernutrition and the characteristics of the families, or the perception of having economic problems at the end of the month, but it was slightly higher in those families where both parents were unemployed. Excess of weight was higher in children of non-Spaniard parents (44% vs 32%, p < 0.0001), as well as in those families with economic problems (41% vs 31%, p = 0.0005). There was a trend in increased excess of weight with age, both in boys and in girls.

Figure 1. Nutritional status of the whole sample. Malnutrition: BMI < -2 SD; overweight: BMI > +1 SD; obesity: BMI > +2 SD.

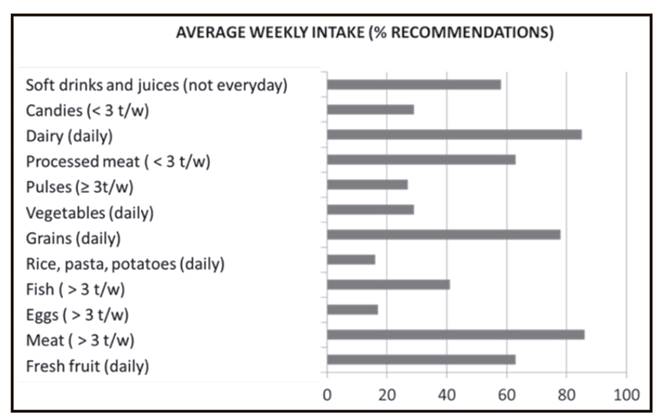

Regarding feeding habits, 96% of the sample had breakfast daily, although only 88% were children from families where one of the parents was unemployed. A whole breakfast (grains, dairy and fruits) was taken only by 40%. Two thirds of the participants had lunch at school (63%), with a higher percentage (67%) in single-parent families as well as in families with economic difficulties. Only for meat, grains and dairy, the weekly intake was close to the recommendations (80% of the sample followed recommendations (Fig. 2). On the other hand, weekly intake of soda or soft drinks was clearly above recommendations: 2.3 times/week. This intake was higher in siblings of foreign couples (2.42), and in siblings from families where the father was unemployed (2.51), as well as in those with obesity in the anthropometric evaluation (2.42).

DISCUSSION

By the end of the 2000s, the economic situation in many European countries started to deteriorate, leading to social insecurity and to worse health status. According to the UNICEF report, child poverty increased in Spain between 2007 and 2013, during the economic downturn that affected most part of Europe. This fact was associated with a decrease in family expenditure, changes in feeding habits, loss of housing and rising social inequity. Most studies suggested that the economic crisis has harmed children's health, and disproportionately affected the most vulnerable groups 10. We chose to perform the study only in public schools in Madrid, as probably the highly risk population attend them.

In adults, a shift towards less healthy behaviors was noticeable after the starting of the economic crisis 11. In an Italian study with representative samples of the Italian population, comparing periods 2005-2007 and 2009-2012, a reduction of meat, fruit and vegetable consumption, increase on snacks and legumes frequencies and less fish and meat presence on diet were observed, but with wide differences according to social position, as well as geographical area 12.

Home environment is a key factor in the development of obesity in children 13. In our study, as well as in others performed in different parts of Spain 14 or in other countries 5,15,16, children from lower income households were at a higher risk of being overweight compared with their peers from higher-income households. It is well-known that there are clear differences among social classes when comparing food habits. Subjects from LSC have a higher trend to consume an unhealthy diet, and to eat less fruits and vegetables 17,18. This situation is called food poverty or food insecurity 19. In Spain, this trend was even previous to the economic turndown, but highlighted in the last 10-12 years. At the same time, lower family income is usually associated with lower fitness score. Nevertheless, complex patterns in the association between socioeconomic status and overweight exist; age, country family precedence, as well as prevalence of obesity among parents, which were not addressed in our study and merit further research, have their influence.

This situation may even worsen during economic constraints. In Greece, food insecurity levels in low socioeconomic areas, measured using the Food Security Survey Model, were as high as 64.2% in 2012-2013 20, and similar data were obtained in Spain 13.

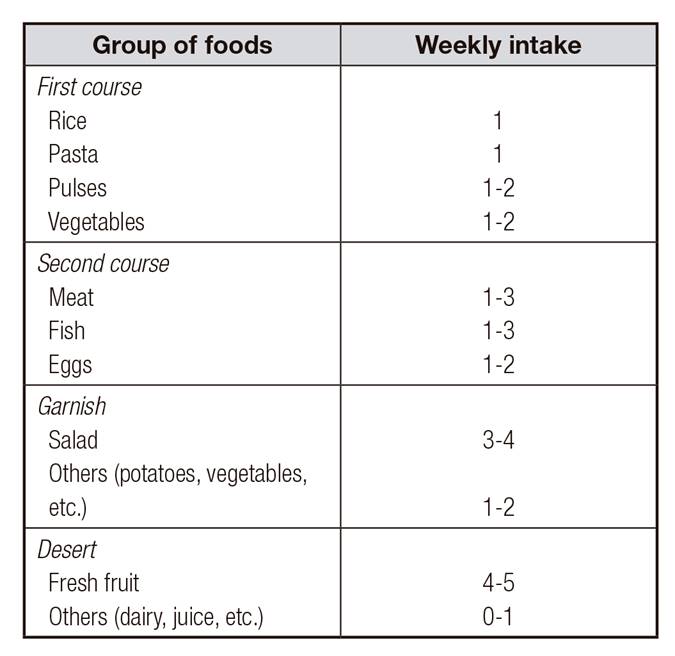

Sixty-three percent (63%) of children in our survey had lunch at school. Participation in a school-based food aid program may reduce food insecurity for children and their families. This may be especially true in times of economic hardship 21. Thus, the results in our survey regarding feeding habits may be modified by the fact of having lunch at schools in near 2/3 of the sample. Although legislation on school lunch has a local scope in Spain, in 2010 a group of experts under the supervision of the Spanish Agency in Food Security agreed on the general guidelines that should be followed regarding foods to be served in schools (lunchrooms, cafeteria and vending machines) 22 (Table 1). The school food environment plays an important role in children's consumption pattern, so efforts to improve lunches at school or to facilitate the access to school lunch in families with economic difficulties may have a great impact on children's health and well-being 23. Schools are a key setting for preventing childhood obesity 24.

The major strength in the study was the stratification in the whole city and all ages as well as the sample size. One of its major limitations was that weight and height were not measured but reported. Some studies indicate that children and adults tend to underestimate their weight and to underestimate their height, so the impact to our data will be that our figures of overweight and obesity should be biased towards an underestimation of the problem. In addition, the sample may not be representative of school children all over the country or even the city, as only public school attendants were considered. Nevertheless, it is a good start point to design strategies involving schools as well as families to improve dietary patterns and to fight against obesity in the same direction that V. Fuster pointed in the editorial of JACC early this year: "Communities and families need to band together to support each other when they attempt to improve their eating habits" 25.