INTRODUCTION

Enteral nutrition therapy, defined as nutrition provided through the gastrointestinal tract via a tube, catheter, or stoma that delivers nutrients distal to the oral cavity 1, is indicated for individuals with preserved gastrointestinal tract function in clinical situations when oral intake is insufficient or contraindicated 2. At the bedside, the feeding tube is inserted through the nose or mouth into the stomach or duodenum 3. Prior to using the tube, correct positioning should be confirmed by an abdominal radiograph to ensure that the distal end is in the gastrointestinal tract 4,5. The main complications of enteral tube feeding include tube displacement, inadvertent respiratory placement of feeding tubes, and microaspiration 6. In addition, tube displacement may lead to delayed feeding and increased costs due to time spent in tube repositioning and radiographic confirmation 7.

The frequency of accidental tube dislodgement is an important indicator of quality of care. It is defined as an unintentional removal of the tube by the patient due to psychomotor agitation, coughing, nausea, or vomiting, by the nursing staff during manipulation of the patient to perform procedures or examinations and administer medication, or by the patient's companion 8. In our institution, audits conducted in 2016 indicated that, on average, 41.3% of feeding tubes were accidentally removed. The recommended international targets are up to 10% in the ward 9,10. To prevent dislodgement, feeding tubes are secured to the skin on the nose or forehead using adhesive tape. Traditionally, the adhesive tape is wrapped around the tube as a "tie" 11 and again attached to the patient's nose. However, the rate of tube dislodgement with this technique can reach up to 62% 12,13. In addition, the use of adhesive tape can cause patient discomfort, nasal tip necrosis, skin lesions and skin sensitivity reactions.

A study conducted in 1995 with a convenience sample of 103 medical intensive care patients evaluated three different methods for securing feeding tubes: pink tape, clear tape and "butterfly". The authors found a significant difference between groups in the mean time until failure of the securing methods, ranging from 30 hours with the "butterfly" to 100 hours with pink tape 14. More recently, the use of nasal bridles, whereby an anchor of the enteral feeding tube is placed around the vomer bone or nasal septum, has been described as more effective in securing enteral feeding tubes in place than the traditional use of adhesive tape 15. However, nasal bridles are not available in Brazil. In our country, only the feeding tube attachment device (FTAD) from Hollister® is available as an alternative to the traditional method of using adhesive tape alone, but its effectiveness in preventing accidental tube removal has not been described in prospective studies.

The current trial was therefore designed to evaluate the impact of using the Hollister® FTAD compared with the traditional securing method with adhesive tape on the occurrence of accidental enteral feeding tube dislodgement. We tested the hypothesis that the rate of inadvertent enteral feeding tube removal would be lower in patients using the dedicated FTAD than in patients using the traditional method with adhesive tape.

METHODS

STUDY DESIGN

This was a single-center, unblinded, randomized clinical trial of hospitalized adult patients in a clinical ward. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Research Ethics Committee of the hospital institution approved the research protocol. All patients gave their written informed consent before study enrollment. The trial is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (http://clinicaltrials.gov), number NCT03262493.

PARTICIPANTS

Potentially eligible patients were selected from clinical wards (sixth floor south and seventh floor north) at a tertiary care university hospital in Southern Brazil, from June to December 2017. All adults aged 18 years and older in an open enteral feeding system were eligible for inclusion. The exclusion criterion was enteral nutrition by gastrostomy or jejunostomy.

RANDOMIZATION AND BLINDING

Participants were randomly assigned to the dedicated FTAD group or the adhesive tape group using a randomization sequence created on the website http://www.randomization.com. Due to the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to blind the investigators, staff or patients in this study.

INTERVENTIONS

The intervention group had the enteral feeding tube secured with the FTAD (stock number 9786; Hollister Inc., Libertyville, IL, USA), which consists of a layer of hydrocolloid adhesive material over the skin on the back of the nose and a polyurethane clamp for attachment around the enteral feeding tube. The placement of the FTAD followed the manufacturer's instructions. The device was placed in all patients by a research nurse who was previously trained by the manufacturer. The manufacturer provided free of charge the total number of devices needed to perform the study. Replacement of the device occurred every seven days or in the presence of dirt, oiliness, detachment or material deterioration.

The control group had the enteral feeding tube secured with adhesive tape alone placed according to the "tie" technique, as recommended by the hospital standard operating protocol. Replacement of the adhesive tape occurred every 24 hours or in the presence of dirt, oiliness, or detachment. This group was followed by the research nurse regarding the adhesive tape replacement that was routinely performed by the nursing assistants of the institution.

OUTCOMES

The primary endpoint was the number (percentage) of inadvertent enteral feeding tube removal per patient from randomization until the end of follow-up. As secondary outcomes, we evaluated the number (percentage) of patients receiving an enteral nutrition volume ≥ 70% of the prescribed volume and evidence of complications related to each type of intervention (adhesive tape or FTAD), such as nasal necrosis, skin lesions and skin sensitivity reactions.

STUDY LOGISTICS

Patients listed in the hospital management system as receiving enteral nutrition were assessed daily in the clinical wards. These data were tabulated in an eligibility screening worksheet. After inclusion in the study, the investigator informed patients of their allocation group. Sociodemographic and clinical data were collected using a structured questionnaire: age, sex, reason for current hospitalization, comorbidities, use of mechanical restraint, and enteral tube feeding (type of tube, place and date of insertion, securing method, and date when the tube was last attached to the skin).

The incidence rate of accidental enteral feeding tube removal per patient was assessed by reviewing daily records on the patient's electronic medical record, enteral feeding tube re-insertion records, and confirmatory/control radiographs. The volume of enteral nutrition prescribed was collected from the "diet map", available in the hospital management system. This map shows the volume of enteral nutrition prescribed by the dietitian. The actual volume of enteral nutrition delivered was obtained from the records made by the nurse on the patient's electronic medical record.

Patients were followed until the discontinuation of enteral feeding, discharge, or death. Therefore, the follow-up period was the duration of the use of the enteral feeding tube.

SAMPLE SIZE

Sample size was calculated using WinPepi based on a systematic review that compared the effectiveness of nasal bridles with the traditional method of adhesive tape alone and found a rate of accidental tube removal of 40.7% (odds ratio, 0.16) in the adhesive tape group 15. For a power of 80% and a significance level of 5%, a sample size of 52 patients per group was required.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Continuous variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD); those with asymmetrical distribution, as median (25th and 75th percentiles). Categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages. The analysis followed the intention-to-treat principle. Regarding baseline characteristics and intervention effects, Student's t test or Mann-Whitney test were used for continuous variables and the Chi-square test was used for categorical variables. The incidence rate of accidental enteral feeding tube removal was calculated according to the following formula: [(number of accidental tube removals / total number of patients * mean duration of tube use)*100] 16. A two-sided p value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Analyses were performed using PASW (SPSS Inc., Quarry Bay, Hong Kong, China), version 20.0.

RESULTS

POPULATION STUDIED

Of the 137 patients who were screened, 104 met the inclusion criteria and consented to participate in the study (Fig. 1), being evenly distributed in both groups for intervention. The main reason for exclusion was the use of gastrostomy. After randomization, two patients died in the FTAD group and three in the adhesive tape group. Deaths during the follow-up period were not related to accidental tube removal, but to the patient's clinical complications. Therefore, these deaths were not attributed to effects related to the research protocol.

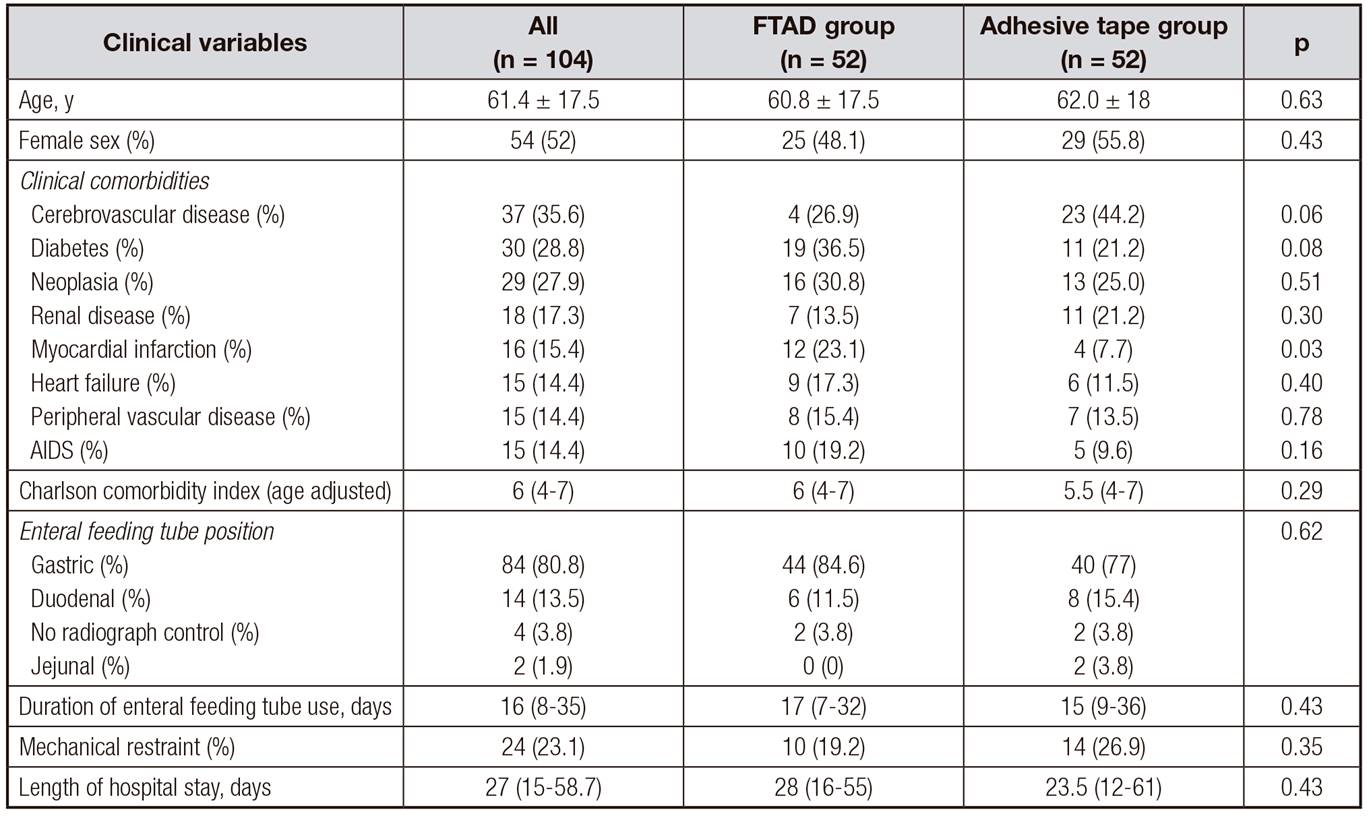

Most patients were women with cerebrovascular disease (35.6%), diabetes (28.8%) and neoplasia (27.9%). There were more cases of acute myocardial infarction in the FTAD group, but other baseline clinical characteristics were similar between the two groups, including Charlson comorbidity index, use of mechanical restraint, and duration of enteral feeding tube use (Table 1).

Table I. Clinical characteristics of the study population

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, frequency (%) or median (25th percentile, 75th percentile). FTAD: feeding tube attachment device.

EFFECT OF INTERVENTION STRATEGIES ON ACCIDENTAL ENTERAL FEEDING TUBE REMOVAL

Of the 39 (37.5%) cases of accidental tube removal, 16 (30.8%) occurred in the FTAD group and 23 (44.2%) in the adhesive tape group (p = 0.22) (Fig. 2). The overall incidence rate of inadvertent enteral feeding tube removal was 1.7%. The rate per group was 1.9% in the adhesive tape group vs 1.4% in the FTAD group. When evaluating the number of times each patient had an inadvertent tube removal, in 50.0% (n = 8) of cases in the FTAD group the tube was removed only once; in 37.6% (n = 6), twice; in 6.2% (n = 1), four times; and in 6.2% (n = 1), ten times. In the adhesive tape group, in 56.5% (n = 13) of cases the tube was removed only once; in 26.1% (n = 6), twice; in 8.7% (n = 2), five times; and in 8.7% (n = 2), eight times (p = 0.33). The number of times the accidental enteral feeding removal was not different between groups (p = 0.43). In most cases, the tube was dislodged by the patient (88.0%), followed by dislodgement by the nursing staff during bathing (9.4%) and transportation for examinations (2.6%).

SECONDARY OUTCOMES

The mean percentage of enteral nutrition delivered to patients was 58.5% (SD, 23.5%) of the prescribed volume. Patients in the FTAD group received a mean of 60.0% (SD, 21.0%) of the prescribed volume, while patients in the adhesive tape group received a mean of 57.0% (SD, 25.0%) (p = 0.61). Only 43 patients (41.3%) received a minimum of 70% of the volume of enteral nutrition prescribed, with no significant difference between the groups: 42.3% in the FTAD group vs 40.4% in the adhesive tape group (p = 0.84).

Three patients developed skin lesions due to the tube securement practice. One patient developed nasal necrosis in the FTAD group, while in the adhesive tape group, one patient had nasal necrosis and another patient had hyperemia.

DISCUSSION

The present study found an overall rate of 37.5% of accidental enteral feeding tube removal, with no difference between the FTAD and adhesive tape groups. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the impact of using the Hollister® FTAD in clinical practice compared with the traditional method of using adhesive tape on the accidental dislodgement of enteral feeding tubes.

A rate of approximately 40% has been reported for accidental enteral feeding tube removal with the use adhesive tape as the securing method 17,18. In the present study, similar to the findings of Cervo et al. 16 in clinical patients, the rate of accidental tube dislodgement with the use of adhesive tape was 44.2%. Pereira et al. 19, however, found a rate of 56% in critically ill patients. Brandt and Mittendorf 20 reported a reduction from 38.1% to 4.2% in the proportion of accidental tube dislodgement with the use of nasal bridles.

Enteral nutrition therapy plays an important role in preventing malnutrition, which is associated with increased length of hospital stay, mortality, and health care costs 21. Tube dislodgement delays the administration of enteral nutrition due to time spent replacing or repositioning tubes and confirmation of the tube position. Consequently, patients may receive less than prescribed enteral nutrition. Studies of critically ill patients report that it is common not to achieve goal feeding rates due to the performance of examinations, procedures, and tube malposition 22,23. A multicenter study found that patients on enteral nutrition received only 59% of their energy needs 24. Other studies reported that, for different reasons, patients received less than 40% of the volume of enteral nutrition prescribed 25,26,27. Our data showed that fewer than half of the patients (41.3%) received at least 70% of their prescribed enteral nutrition.

The occurrence of skin-related adverse events at the tube insertion site did not differ between the FTAD and adhesive tape groups. In the study conducted by Cervo et al. 16, the enteral feeding tube was secured in the traditional manner by adhesive tape alone in all patients and no type of skin lesion was reported.

Our study has potential limitations. One is related to the follow-up time and mental status in some patients requiring mechanical restraint to avoid accidental withdrawal of the enteral feeding tube. However, this is the first study to evaluate the use of a dedicated FTAD for securing enteral feeding tubes. In addition, in adults, a dedicated FTAD may be an option for individuals with allergy to adhesive tape or those who are uncomfortable with the traditional securing method with adhesive tape. Finally, because this study is the first to evaluate the performance of the Hollister® FTAD, our findings may be of great value in future studies for comparison purposes and for investigation in other patients, such as surgical patients and intensive care patients.