INTRODUCTION

Swallowing is defined as the activity of transporting solid and liquid substances, as well as saliva, from the mouth to the stomach. It implies the coordinated participation of anatomical areas that, through movements and pressures, allow food to be conducted efficiently and safely through the digestive tract (1). Dysphagia represents any type of alteration or difficulty in swallowing, which can occur in any of its phases (oral, pharyngeal, or oesophageal). Depending on the swallowing phase that has been affected, we can classify it into preparatory oral dysphagia, oral phase dysphagia, pharyngeal dysphagia, and oesophageal dysphagia. However, from the practical point of view, dysphagia is classified into two large groups: oropharyngeal dysphagia and oesophageal dysphagia. From the pathophysiological perspective, functional and structural alterations can be the cause of this syndrome (2).

The prevalence of dysphagia varies depending on the definition used, the study population, and the sensitivity of the screening or diagnostic technique involved. It has been estimated that between 16 % and 22 % of the population over the age of 50 have dysphagia. The prevalence of swallowing disorders in those over 65 years is 40 %, and above 60 % among nursing home residents. The highest prevalence (> 80 %) has been found in hospitalised patients with dementia, especially in the more advanced stages of the disease (3,4). The ageing process causes anatomical, neurological, and muscular changes that result in a loss of functional capacity that may affect swallowing. In the elderly who do not have health problems, these changes are defined as presbyphagia, and are not necessarily pathological. However, when these changes in swallowing physiology occur in frail elderly people, with comorbidities and polymedication, the risk of dysphagia increases (5,6).

Dysphagia has a profound effect on nutritional status as a result of decreased intake due to a loss of swallowing efficacy and fear of eating. The most frequent type of malnutrition in patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia is the caloric one, with preservation of visceral protein and a significant depletion of muscle mass and the fatty compartment. In Spain, 40 % of hospitalised patients with dysphagia are at risk of malnutrition. When focusing only on patients who are 70 years of age or older, this percentage rises to 60 % (7). Because of this high risk of malnutrition, the European Society for Swallowing Disorders (ESSD) recommends continuous monitoring of the nutritional status of patients with dysphagia (8). However, despite the current ESSD recommendations, only one in four patients with dysphagia receive nutritional support (7). In addition, the decrease in fluid intake due to dysphagia causes an imbalance of body fluids that leads to increased mortality in hospitalised patients (9). One study found that daily water intake in patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia was only 22 % of the recommended amount for these patients (10).

Up to 50 % of neurological patients and the elderly have alterations in swallowing safety (penetrations and aspirations), with a high proportion of silent aspirations (not accompanied by cough), during videofluoroscopy, and a 50 % risk of developing aspirative pneumonia, which is associated with an increase in mortality for 50 % of these patients. These respiratory infections represent the main cause of mortality in patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia, and have also been associated with an increase in hospital stay and hospital readmissions (11).

Currently, there are multiple tests for the screening and diagnosis of dysphagia. One of the most commonly used is the Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10) questionnaire. This method, useful for the screening of dysphagia in patients with preserved cognitive levels, includes 10 questions about swallowing that the patient has to score from 0 (no problem) to 4 (a serious problem). A score greater than 3 denotes the potential presence of dysphagia (12). This tool is widely used in the ambulatory setting, but we have little data about its usefulness in hospitalised patients. We designed this study to establish the feasibility of using the EAT-10 as a screening tool for dysphagia in hospitalised patients, to determine the prevalence of dysphagia in key hospitalisation units where there are high-risk patients (such as Internal Medicine and Neurology), and to find out whether there is a relationship between EAT-10 results and nutritional status, hospital stay, in-hospital mortality, and readmissions at 30 days.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A cross-sectional study was designed to reach the objectives, and was developed in the acute hospitalisation wards of the Departments of Internal Medicine and Neurology of the University Hospital Complex at A Coruña. This tertiary hospital assists a reference population of 505,797 people, with 1,415 hospitalisation beds installed. The study took place between January and April 2019.

This study was carried out respecting the Helsinki Declaration of the World Medical Association, the Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine, and the Spanish legislation about human research. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the research ethics committee of the hospital.

A sample size of 118 patients was estimated, based on the prevalence of dysphagia obtained from the PREDYCES study (20.6 %), an estimate of 1500 patients admitted in the study period, a confidence level (1-α) of 95 %, and an accuracy of 7 % (7). Inclusion criteria included age over 18 years and scheduled or urgent admission to the Neurology and Internal Medicine hospitalisation units. Patients who had been hospitalised for less than 24 hours, patients admitted to the Neurology or Internal Medicine hospitalisation unit but in charge of other hospital services, and patients in terminal stages of their disease, in whom death was expected in the following hours, were excluded.

The recruitment was performed consecutively based on the patients admitted to the above-mentioned wards within the first 24 hours of hospitalisation, upon request of an informed consent. Patients admitted during the weekend or non-working days were recruited the next working day (maximum, 48 hours after admission).

The presence of dysphagia was screened using the EAT-10, and the risk of malnutrition was assessed using the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST). Both questionnaires were administered by the researchers. Height and weight were measured with the stadiometer and scales at each ward, which are periodically calibrated. When it was not possible to obtain these measures directly, researchers used the alternative measurements described by the British Association of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition (BAPEN) (13). The comorbidities of patients were measured using the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), considering a high comorbidity level when a result higher than 3 points was obtained (14). Data such as admission date, discharge date, main diagnosis, mortality during admission, and 30-day readmissions were obtained from the medical records.

Qualitative data were summarised as percentages. The normal distribution of quantitative data was checked with the Shapiro-Wilk test and summarised using mean and standard deviation. Qualitative variables (e.g., gender, mortality, readmissions, prevalence of malnutrition) were compared using the chi-squared test. Continuous quantitative variables (e.g., hospital length of stay or age) were compared using Student’s t-test for independent measurements (or the Mann-Whitney U-test). A p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

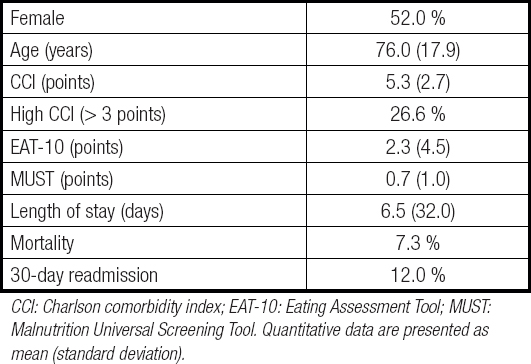

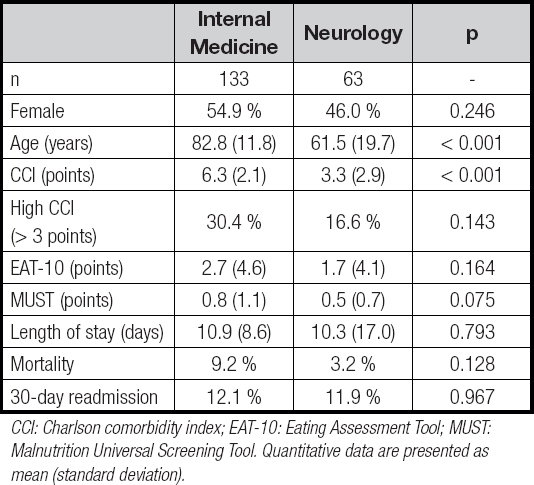

The study recruited 196 patients, whose general characteristics are presented in table I. Most patients were recruited at the Internal Medicine wards (67.9 %). The differences between patients in each ward are summarised in table II.

Table I. General characteristics of the patients

CCI: Charlson comorbidity index; EAT-10: Eating Assessment Tool; MUST: Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool. Quantitative data are presented as mean (standard deviation).

Table II. Comparison of patients admitted to the Neurology and Internal Medicine units

CCI: Charlson comorbidity index; EAT-10: Eating Assessment Tool; MUST: Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool. Quantitative data are presented as mean (standard deviation).

The EAT-10 was administered to 158 of the 196 patients included in the study (80.6 %), and was positive in 42 (26.6 %) of the 158 patients who could be screened. Patients where EAT-10 could not be administered were older (82.5 [18.0] yrs vs. 74.4 [17.5] yrs; p = 0.012) and had a higher CCI (6.3 [2.2] points vs. 5.1 [2.9] points; p = 0.018). Patients admitted to Internal Medicine were more frequently unable to answer the questionnaire (23.3 % vs. 11.1 %; p = 0.044). There were no significant differences in the prevalence of positive results in the EAT-10 according to hospitalization ward: Internal Medicine, 30.4 % vs. Neurology, 19.6 % (p = 0.143). The differences found between patients according to EAT-10 screening are analysed in table III.

Table III. Differences among patients according to the EAT-10 screening

CCI: Charlson comorbidity index; EAT-10: Eating Assessment Tool; MUST: Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool. Quantitative data are presented as mean (standard deviation).

According to MUST, 19.6 % of patients were at risk of malnutrition, without significant differences between hospitalisation units: Internal Medicine, 23.7 % vs. Neurology, 12.3 % (p = 0.084). There were no differences in the prevalence of patients with risk of malnutrition between patients with a positive or negative EAT-10 (15.8 % vs. 16.3 %, p = 0.936). MUST was more frequently positive among patients who could not answer the EAT-10 (58.3 % vs. 6.2 %, p < 0.001).

The results of the EAT-10 did not predict clinical outcomes: there were no differences in hospital length of stay [positive, 11.9 (13.3) [days vs. negative, 9.8 (11.2) days; p = 0.256], in-hospital mortality (positive, 4.9 % vs. negative, 4.3 %; p = 0.888), or readmission rate (positive, 9.4 % vs. negative, 12.9 %; p = 0.596). Mortality was higher in patients whose EAT-10 could not be performed (18.9 % vs. 4.5 %, p = 0.002).

DISCUSSION

In this cross-sectional study carried out in the Neurology and Internal Medicine hospitalisation units of a university hospital, the prevalence of patients at risk of dysphagia detected with the EAT-10 was 26.6 %, a higher rate than that obtained in the PREDyCES® study (20.5 %) (7). There were no differences in the prevalence of dysphagia between the two studied departments, in which presumably we can find patients at higher risk of swallowing disorders due to ageing, frailty, and neurological disorders (e.g., dementia, cerebrovascular disease). According to studies, any type of cognitive impairment is associated with dysphagia. The prevalence of swallowing disorders in patients with dementia could reach 93 % (3,15). In cerebrovascular disease, it is the most common cause of admission to the Neurology hospitalisation unit; prevalence increases to 37-45 % when questionnaires are used, and to 78 % when assessed with videofluoroscopy (3). The questionnaire was more frequently positive in women, unlike what was found in the study that validated the Spanish EAT-10, which could be possibly related to older age and higher morbidity (12).

The EAT-10 was realisable in 80.6 % of the studied patients. In the Neurology unit, 88.9 % of subjects could answer the questionnaire, compared to 76.7 % in the Internal Medicine unit. No differences were found between men and women when they were able to answer the questionnaire; however, differences were found in age. Thus, patients who cannot fill in the screening test were older and had a higher score in the CCI as well. Patients who could not perform the test exhibited a higher mortality rate than those who were able to fill it out. Many studies that used the EAT-10 as a screening tool excluded patients with cognitive impairment or serious neurological disease who were unable to answer the items in the questionnaire, so they did not test the actual feasibility of this tool in a hospital environment (12,16-18).

In this study, malnutrition, in-hospital mortality, mean hospital stay, and 30-day readmissions were not increased in patients with a positive EAT-10. These results are in contrast with what previous studies showed (3,16-18). In patients who were unable to perform the EAT-10 there was a higher mortality rate than in those who could perform it. Together, these data indicate that the EAT-10 cannot be used in patients at higher risk of worse clinical outcomes. In contrast, MUST could be performed in all the recruited patients. Both the weight and height of the patient can be indicated by the patient himself or by their family or caregiver. If they fail to provide the data, height can be estimated by the length of the ulna.

The study was carried out at a time of the year with a large number of patients admitted for influenza, so perhaps, if the study were repeated at another time of the year, the prevalence of dysphagia in Internal Medicine could change, and even the feasibility of the test, since there would be other types of patients admitted to this unit. In addition, a larger sample size would possibly reveal significant differences among some parameters related to dysphagia. As a strength of the study, we can highlight that patients with potential risk of dysphagia were not excluded, so the results show the real utility of the EAT-10 in the analysed hospital units.

CONCLUSIONS

The prevalence of dysphagia risk as estimated with the EAT-10 in our Neurology and Internal Medicine hospitalisation units is 26.6 %. The questionnaire was answered only by 80.6 % of the patients in these departments, and it was less frequently practicable in older patients, patients with more comorbidity, and patients at risk of malnutrition. The results of the EAT-10 were not related to worse clinical outcomes, such as hospital stay, mortality, and readmission. We can conclude that the EAT-10 has limited utility for inpatients at Internal Medicine and Neurology wards, and other strategies focused on the detection of dysphagia should be studied.