Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Anales de Psicología

versión On-line ISSN 1695-2294versión impresa ISSN 0212-9728

Anal. Psicol. vol.33 no.3 Murcia oct. 2017

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.33.3.251321

Design and validation of a questionnaire to assess cooperative learning in educational contexts

Diseño y validación de un cuestionario de medición del aprendizaje cooperativo en contextos educativos

Javier Fernández-Rio1, José A. Cecchini, Antonio Méndez-Giménez1, David Méndez-Alonso2 and José A. Prieto2

1 Facultad de Formación del Profesorado y Educación; Universidad de Oviedo (Spain).

2 Facultad Padre Ossó; Universidad de Oviedo (Spain).

ABSTRACT

The goal of the present study was to design and validate an instrument to assess the basic elements of cooperative learning, as well as a cooperation index. 11.202 primary education (grades 5, 6), secondary education and baccalaureate students (5.838 males, 5.364 females) from 68 different schools in 62 cities all over Spain agreed to participate. The age range was 11-18 years. The participating students had experienced several cooperative learning techniques during the last six months. The first version of the questionnaire was assessed by a group of experts. A pilot study with 60 students similar to the target sample was conducted on the second version of the instrument. The final version underwent several statistical tests. The Cooperative Learning Questionnaire included five subscales: Promotive Interaction, Positive Interdependence, Individual Accountability, Group Processing and Interpersonal skills. Factorial and confirmatory analysis showed that all reliability indices were acceptable, even under the most difficult conditions. The questionnaire showed adequate convergent, discriminant and concurrent validity. Results showed that it is an easy instrument to assess all the basic elements of cooperative learning in primary, secondary and baccalaureate students and obtain a global cooperation factor.

Key words: cooperation; primary; secondary; baccalaureate.

RESUMEN

El objetivo del estudio fue elaborar y validar un instrumento que pudiera evaluar los elementos fundamentales del aprendizaje cooperativo, así como proporcionar un factor de cooperación. Participaron 11.202 estudiantes de educación primaria (5o-6o curso), secundaria y bachillerato (5.838 varones, 5.364 mujeres) de 68 centros educativos en 62 ciudades españolas repartidas por toda su geografía. Las edades oscilaron entre los 11 y los 18 años. El único requisito para participar era haber experimentado varias técnicas de aprendizaje cooperativo en los últimos 6 meses. Tras elaborar una primera versión y ser sometida sucesivamente a un juicio de expertos y un estudio piloto se realizó un segundo estudio en el que se sometió la versión definitiva a diferentes pruebas estadísticas. El Cuestionario de Aprendizaje Cooperativo está formado por cinco sub-escalas: Interacción Promotora, Interdependencia Positiva, Responsabilidad Individual, Procesamiento Grupal y Habilidades Sociales. Los análisis factoriales confirmatorios mostraron que todos los índices de fiabilidad eran aceptables, incluso bajo las condiciones más exigentes. El cuestionario mostró una adecuada validez convergente, discriminante y concurrente. Se confirma como un instrumento sencillo para evaluar todos los elementos fundamentales del aprendizaje cooperativo en estudiantes de primaria, secundaria y bachillerato y proporcionar un factor de cooperación global.

Palabras clave: cooperación; primaria; secundaria; bachillerato.

Introduction

Cooperative learning has become very relevant in the last few years, but it has a long history of more than 50 years reflected in the works of Dewey (1915) or Deutsch (1949). There exits many definitions on cooperative learning, but it could be briefly defined as small groups where students work together to maximize their own and others' learning through common goals, depending on each other to achieve them (Johnson, Johnson & Holubec, 2013; Sharan, 2014). Several research works have showed the benefits of this framework to achieve different positive outcomes: performance, motivation and social skills (Gillies, 2014; Kyndt et al. 2013; Slav-in, 2014), in subjects as different as Maths (Pons, Prieto, Lomeli, Bermejo & Bulut, 2014), science (Howe, 2013), or physical education (Fernandez-Rio, Sanz, Fernandez-Cando & Santos, 2017). Based on these findings, cooperative learning is considered a methodological tool that can help solve XXIst century students' needs (Johnson & Johnson, 2014).

Four theoretical perspectives on cooperative learning have been highlighted (Slavin, 2014): (1) Motivational: it focuses on the goal structure developed by the teachers in the different tasks, because it can motivate students towards learning (Johnson & Johnson, 2009); (2) Social cohesion: the relations created among group members force students to help each other to learn (Cohen, 1994); (3) Cognitive: to learn, students must go through a cognitive restructuring of the new contents, and cooperative learning helps this reelaboration (Schunk, 2012); finally (4) Development: the interaction between students with different levels of developmental deeply stimulates the students' capacities than when the act individually (Damon, 1984). We must clarify that these 4 perspectives are not exclusive. On the contrary, they complement each other (Slavin, 2014).

Based on the aforementioned, there exist three approaches in cooperative learning: (a) Conceptual: it focuses on the development of global programs (theory and practice), and principles of action to help implement the model (Johnson & Johnson, 2009), (b) Curricular: it focuses on the development of specific and applicable resources to work the main contents of the different subjects (Slavin, 1995) and (c) Structural: it focuses in the organization on the teachinglearning context to promote student interaction (Kagan, 1992). Again, these approaches are not exclusive, they complement each other.

Despite the different approaches and frameworks, there is general consensus on the five basic or essential elements o characteristics that any cooperative learning structure must contain (Johnson & Johnson, 2013): Positive Interdependence. group members are dependent on each other to achieve the goal, Promotive Interaction: group members must be in direct contact with other to cheers and support during the task, Individual Accountability, each group member should be responsible of a piece of the global work, Group Processing, the group must reflect, debate, talk... process the information available, and Interpersonal Skills, as a consequence of the previous elements, group members will develop interpersonal communication skills (i.e., cheer, congratulate, actively listen...), management skills (i.e., respect, share, mediate...) or leadership skills (i.e., explain, suggest, direct...). Significant authors such as Kagan (1992) suggest that besides positive interdependence and individual accountability, there are two other elements that are fundamental in any cooperative learning structure. The first one is equal participation, which means that teachers should create frameworks where all students could have a similar participation time. The second one is simultaneous interaction it refers to the connections among students during the tasks, which are increased in cooperative learning through the small groups.

Over the last years, different instruments have been developed to assess cooperative learning and its elements in different educational contexts. The Classroom Life Management (Johnson & Johnson, 1983) includes subscales to assess the global cooperative learning, positive interdependence ad other elements such as assessment, teacher academic support or heterogeneity. Later, the Cooperative Learning Observational Schedule (Veenman, Benthum, Bootsma, Dieren & Kemp, 2002) was developed. It includes the five basic elements of cooperative learning previously explained. However, it was designed to be used by the external observers, not the participants, to assess the cooperative learning level. Afterwards, the Quality of Cooperative Learning y el Conditions for Cooperative Learning (Hijzen, Boekaerts & Vedder, 2006) are introduced. The first one assessed positive interdependence and interpersonal skills, and teaching behaviour or academic support tasks the second one. Lately, the Cooperative Learning process Scale (Bay & Çetin, 2012) was developed, and it includes all the basic elements. However, it has a large number of items (48) and it was validated using and very limited number of participants (177). Recently, two new instruments have been presented. The Cooperative Learning Application Scale (Atxurra, Villardón-Gallego & Calvete, 2015) includes four out of five basic elements (it does not include individual accountability), and others such as assessment or tutorship, and it was developed to be used with university students. Finally, the Learning Team Potency Questionnaire (León del barco, Mendo, Felipe-Castaño, Polo del Río & Fajardo-Bullón, 2017) was developed to assess the effects of cooperative learning techniques in university contexts and it does not assess its basic elements. Finally, there are other instruments that include the word cooperation in their title, but they really assess team work, the Questionnaire to Assess Cooperation in Higher Education (García, González & Merida, 2012) or the Self-Assessment Instrument of Group Interaction (Ibarra & Rodriguez, 2007).

All the previously described instruments can be included in a category called, second generation research (Melero & Fernandez, 1995), where the cooperative learning process itself and not its effects or outcomes is assessed to be able to see if there is a true cooperative learning group. Pujolás (2009, p. 234) developed the Degree of Cooperation of a group to assess "how cooperative it is" and this degree depends on two variables. the amount of time that the group works as a team (expressed in percentage) and the quality of this work (expressed through and quality index from 0=minimum to 6= maximum) based on the essential elements of cooperative learning (i.e., positive interdependence of ends, simultaneous interaction, self-assessment...). This assessment instrument has two weaknesses. on the one hand, as mentioned in a previous tool, an external observer, and not the participants, must assess the cooperative learning displayed, and, on the other hand, it does not assess all the essential elements.

Based on the aforementioned, that main goal of the present study was to design and validate an easy-to-use questionnaire to assess the five basic elements of cooperative learning in primary, secondary and baccalaureate students. A second goal was to obtain a global cooperation factor from the same instrument.

Method

Participants

A total of 11.202 students (5.838 males and 5.364 females) from Primary (1.203 grade 5, 1.667 grade 6), secondary (2.144 grade 7, 2.077 grade 8, 1.914 grade 9 and 1.688 grade 9), and baccalaureate (512) enrolled in 68 different schools from 62 Spanish cities in all the Spanish Autonomous Communities except Navarra and Extremadura agreed to participate. Age ranged from 11 to 18 years (M= 13.34, SD= 1.78). The only requirement to be able to participate in the study was to have experienced in their classes several cooperative learning techniques during the previous six months. To validate a research instrument, the scientific literature recommends a minimum of 5 observations for each free parameter to estimate, but the most adequate is no less than10 subjects (Rial, Varela, Abalo & Lávy, 2006). This last number has been widely exceeded in the present study.

Instruments

The Cooperative Learning Questionnaire (CAC). The initial version was elaborated by a group of university professors with ample research experience in Educational Sciences and Cooperative Learning following Muñiz, Fidalgo, García-Cueto, Martinez and Moreno (2005). To develop each item, all the existing questionnaires (presented in the introduction section) on cooperative learning were used. Each of the professors involved in the process created a set of items. This set was reviewed independently by each professor and later jointly to decide the final items to be included in the questionnaire. The initial version included a total of 30 items, 6 items per each of the five dimensions. interpersonal skills, group processing, positive interdependence, promotive interaction, and individual accountability. A 5-point likert scale was selected as the response format (from 1= totally disagree to 5= totally agree) because it is considered the best option for the age of the participants and for the validation process (Herrera, 2007). The stem: "In class..." was added at the beginning of the questionnaire. To assess the instrument's content validity and applicability, the first version underwent a process of double debugging:

1) Experts trial: six outstanding professors belonging to six different Spanish universities assessed item suitability using a 5-point likert scale (Mussio & Smith, 1973). Following Hernandez-Nieto (2002), the Content Validity Coefficient (CVC) was used to assess the degree of agreement among several experts (it is recommended between three and five). The mean average obtained on each item is calculated and the following formula is used: CVCi = Mx (mean average of the item)/Vmax (maximum possible score of the item). In the present study, the assigned error to each item was also calculated (0.00032), to reduce the possible bias introduced by any of the experts. The final CVC was calculated= CVCi-0.00032. In the present study, only items with a CVC ≥ 0.90. The second version of the questionnaire was reduced to 25 items.

2) Pilot study: 60 primary, secondary and baccalaureate students agreed to participate. The goal was to modify and/or eliminate items difficult to understand or with errors. One item per scale was eliminated, and the final version of the questionnaire was reduced to 20 items (Table 1).

The Cooperative Learning Application Scale (Atxurra et al., 2015). To assess the concurrent validity of 4 out of the 5 sub-scales of our questionnaire, the following dimensions of the CLAS were used: social skills (4 items), group processing (4 items), positive interdependence (4 items) and promotive interaction (4 items). Participants are asked to remember when they feel more successful at school: "I feel successful at school when...". They answered in a 5-point likert scale from (5) totally agree to (1) totally disagree. The different subscales showed adequate internal consistency (≥ 0.70).

Personal and Social Responsibility Questionnaire (Escartí, Pascual & Gutierrez, 2011). To assess the concurrent validity of the sub-scale individual accountability of our questionnaire, the responsibility subscale (4 items) of this questionnaire was used. It has always showed adequate internal consistency (≥ 0.70). In our study, any mention to a particular subject was erased (the original version was develop for physical education).

Procedure

First, permission was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the researchers' university. Second, the largest number of schools that were using cooperative learning in the last grades on primary education, secondary education and baccalaureate in Spain was contacted. Two selection criteria were set: (1) participating students had experienced at least five different cooperative learning techniques in one or several subjects over the last six months prior to data collection, and (2) the participating students' teacher had to demonstrate specific training on cooperative learning (a minimum of 50 hours of theory and practice). The goal was to select schools who were implementing, at least in one of their subjects, cooperative learning on a regular basis. The aim of the study was explained to them and their collaboration was asked. At the same time, an on-line version of the questionnaire was developed to provide an easy access to the participants. Permission from all the schools was obtained, as well as an written consent from the participating students' parents or tutors. Finally, access to the on-line version of the questionnaire was granted to the students.

Statistical analyses

All data was analyzed using the statistical package SPSS, version 22.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL). A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to assess the questionnaire, which consisted of 5 sub-scales or latent factors, composed of 4 items or indicators. Later, a second-level confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to define a global cooperative learning factor, determined by 5 latent factors.

Initial analyses examined the multivariate analysis of the indicators. Results of the multiple kurtosis coefficient (Mardia's coefficient = 104.50) indicated that the sample did not follow a normal distribution (Mardia, 1974). Based on this result, the program EQS 6.2 was used (Bentler, 2005). Therefore, analyses were based on the Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square statistic (S-Bχ2; Satorra & Bentler, 1988), rather than the usual MLχ2 statistic, as it serves as a correction for χ2 when distributional assumptions are violated (Curran, West & Finch, 1996; Byrne, 2008).

The evaluation of the sample's goodness-of-fit data was performed using multiple criteria (Byrne, 2008): the robust versions of the Comparative Fit Index (*CFI; Bentler, 1990), the Root Mean-Square Error of Approximation (*RMSEA; Browne & Cudeck, 1993), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). To complete the analysis, the confidence interval to 90% provided by *RMSEA was also included (Steiger, 1990).

To assess the convergent validity the statistical significant of each construct's indicator was examined. Cronbach's alpha was also calculated to assess the scores' validity (Nunnally, 1978).

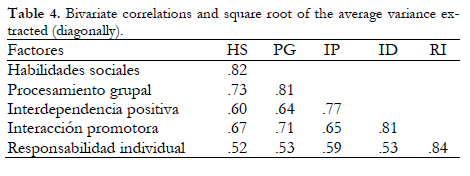

Discriminant validity was assessed comparing the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) with the correlation among constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Due to the large sample, no complementary analysis was conducted to determine if the number of participants was adequate.

To contrast the factor structure of the questionnaire a multigroup confirmatory factor analysis was conducted. It allows the assessment of the factor structure invariance using different samples based on gender (male, female), and age (11-13 years, 14-17 years), which produced four groups (Byrne, 1998).

To assess if the model parameters remained invariant through the four samples, an invariance multistep was conducted (Bollen, 1989; Marsh, 1993). Following Byrne (1998) the first step is to establish a reference model for all the groups in one sample. The invariance test begins with the least restrictive model, where only one reference model is included. It is a non-variant step and it produces a firm base for the later comparison between models (Marsh, 1993). The factor loadings are forced to remain invariant among groups. The next step is to limit the covariance matrix among groups, with the factor loadings restricted. In the following step the variances among groups are restricted, with the factor loadings and the co-variances still restricted. Finally, the singularity (error) is established equally among groups, with the factorial loadings, the covariances and the variances still restricted.

Results

Confirmatory factor analyses

All the fit indices showed that the model had a good fit (Byrne, 2008): S-Bχ2 (160) = 2574.51, p < .001; *CFI = 0.953; *RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.037 (0.035-0.038); SRMR = 0.02. The second-level confirmatory factor analysis also had a good fit: S-Bχ2 (165) = 3134.01, p < .001; *CFI = 0.942; *RMSEA (90% CI) = 0.040 (0.039-0.041); SRMR = 0.032. Table 2 shows correlations among all items. It can be observed that the highest correlations were obtained among items which measure the same dimension.

Convergent validity and reliability

Table 3 shows that all standardized loadings (λ1) and all critical values t are well above the minimum values required of 0.50 and 1.96 (p < 0.05), respectively (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson & Tatham, 2006). Cronbach's alphas are also above 0.70.

Discriminant validity

To assess this validity, the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) was compared to the correlation between all the constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Table 4 shows all correlations, and in the diagonal the square root of the AVE. The discriminant validity is observed when the square root of the AVE is higher that the correlation between all the constructs. Results showed that there is discriminant validity between them.

Multigroup confirmatory factor analysis

An invariance multistep analysis was conducted to test the questionnaire's factorial structure and be able to use it in different populations (Bollen, 1989; Byrne, 1998; Marsh, 1993). It begins with the least restrictive model, where only the reference model is included: the five independent latent factor solution (Mforma). Then, factor loadings are forced to remain invariant among groups (Mcargas). In the next step the covariance matrix is limited, and the factor loadings are also limited (Mcovarianza). Then, the variances among groups are restricted, with the factor loadings and the covariances still restricted (Mvarianza). Finally, the singularity (error) is established equally among groups, with the factorial loadings, the covariances and the variances still restricted (Merror). No significant differences were observed in the S-Bχ2 score. Therefore, the model remained invariant among the four groups. According to Cheung and Rensvold (2002) scores lower than -0.01 in the ΔCFI indicate that the invariance null hypothesis cannot be rejected. Results suggested that the factor structure is invariant in the simple assessed (Table 5).

Table 6 shows means and standard deviations of each of the five factors of the cooperative learning scale for the total simple and for each of the four sub-groups (age x gender).

Concurrent validity

Six linear regression analyses were conducted using the sub-scales of the cooperative learning questionnaire and the cooperation factor as dependent variables and the scores of the sub-scales social skills, group processing, positive interdependence, and promotive interaction from the Cooperative Learning Application Scale (Atxurra et al., 2015) and the sub-scale individual accountability of the Personal and Social Responsibility Questionnaire (Escarti et al., 2011) as independent variables. On each of the six regression analysis the five predictors were introduced in successive steps. Results showed that the different variables selected explain a significant amount of variance of the 5 sub-scales, showing a high predictive value (Table 5). Therefore, results are coherent. In all factors, the variable with the highest predictive value is always its corresponding in the CLAS questionnaire, except in the factor individual accountability that comes second. The reason could be that the Personal and Social Responsibility questionnaire for physical education contexts do not really assess cooperative learning, but responsibility. In the factor group processing, in the last step the results are coherent, but in the first step the factor social skills of the CLAS appears. In the factor global cooperation, the loadings of the different CLAS factor are similar, and the one that has less weight is the Personal and Social Responsibility ques tionnaire for the reason previously mentioned. (Table 7).

Discussion

The main goal of the present study was to design and validate an easy-to-use questionnaire to assess the five basic elements of cooperative learning in primary, secondary and baccalaureate students. A second goal was to obtain a global cooperation factor from the same instrument. Results have showed that both goals have been achieved.

Regarding the first goal, several statistical analyses were conducted in the final version of the Cooperative Learning Questionnaire: confirmatory factor analyses, convergent validity, disciminant validity, multigroup confirmatory factor analysis and concurrent validity. Confirmatory factor analyses showed that all indices were acceptable, even under the most stressful conditions (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Therefore, the questionnaire shows strong construct validity. All Cronbach's alphas were above the minimum recommended of 0.70 (Nunnally, 1978), indicating the reliability was adequate, despite the small number of items. All the standardized loadings (λ) and the critical values t were above the minimum recommended of 0.50 and 1.96, which indicates that the convergent validity was also adequate. Discriminant validity was assessed comparing the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) and the correlation among constructs (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Results showed that there is adequate discriminant validity among constructs. To be able to use the questionnaire in other contexts and test its factor structure a multigroup confirmatory factorial analysis was conducted, using a multistep invariance analysis (Bollen, 1989; Byrne, 1998; Marsh, 1993). Results showed that the proposed model produced similar results in the different groups, suggesting that the factor structure is invariant among the different samples used. Finally, concurrent validity analyses of the sub-scales of the questionnaire and the cooperation factor were conducted through several regression analyses. In all cases, the selected variables explained a significant amount of variance of the sub-scales. Results from all the analyses described show that the Cooperative Learning Questionnaire had adequate psychometric properties.

Prior to the present study, other scales have been developed to assess cooperative learning in different groups of students (Atxurra et al., 2015; Bay & Çetin, 2012; García et al., 2012; Hijzen et al., 2006; Ibarra & Rodríguez, 2007; Johnson & Johnson, 1983; León del barco et al., 2017; Pujolás, 2009; Veenman et al., 2002). All of them have showed some type of weakness: some did not include the five main elements of cooperative learning, others focused on similar methodological approaches (group work), in others a external observer, not the participants, assessed cooperative learning, all were developed for a specific age range (secondary, college), and finally, some had a large number of items, which limits its applicability. The cooperative learning questionnaire presented here has excellent psychometric properties, assesses its basic five elements, a global cooperation factor, and has a limited number of items (20). Furthermore, it has been validated in a very large sample of students of different school levels: primary (5-6), secondary and baccalaureate. All this elements make them an ideal instrument to assess this teaching approach in the three mentioned stages.

Regarding the second goal of the study, a second-level confirmatory factor analysis was conducted where the factor cooperative learning was determined by five latent factors to produce a global cooperation factor. Results showed that all the standardized loadings and the critical values were above the minimum recommended. Cronbach's alpha was 0.89. Both results showed that the factor had strong validity and reliability. To our knowledge, there are no published studies on a cooperative learning factor similar to the one introduced here. Pujolás (2009) developed a tool to assess the degree of cooperation of a group, which could be considered a cooperation factor. It is a valuable tool because it is the first one that allows comparisons among groups. However, from our point of view, it has two weaknesses: an external observer and not the participants assess cooperative learning, and it does not assess its basic five elements. The cooperation factor produced by the cooperative learning questionnaire presented here assesses the five elements and the participants' opinions are evaluated. This factor is a new element for future lines of research in cooperative learning, because it allows researchers to compare groups or frameworks.

Conclusions

The cooperative learning questionnaire has been proven a valid and reliable instrument to assess the five basic elements of cooperative learning: promotive interaction, positive interdependence, individual accountability, group processing and interpersonal skills in primary education students (grade 5 and 6), secondary education and baccalaureate. Moreover, it allows researchers to obtain a cooperative learning factor which has never been assessed. Finally, its size (20 items) makes it an easy-to-use instrument, and its age range (primary, secondary and baccalaureate) a useful tool. All these features make the cooperative learning questionnaire a step forward for the study on cooperative learning in educational contexts.

References

1. Atxurra. C., Villardón-Gallego. L., y Calvete. E. (2015). Diseño y validación de la Escala de Aplicación del Aprendizaje Cooperativo (CLAS). Revista de Psicodidáctica, 20(2), 339-357. [ Links ]

2. Bay. E., and Çetin. B. (2012). Işbirliği süreci ölgeği (ISÖ) geliştirilmesi. Uluslararasi Insan Bilimleri Dergisi, 9(1), 1064-1075. Descargado de: http://www.insanbilimleri.com. [ Links ]

3. Bentler, P. M. (2005). EQS 6 structural equations program manual. Encino. CA: Multivariate Software. [ Links ]

4. Bollen, K.A. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York: John Wiley. [ Links ]

5. Byrne, B. (1998). Structural Equation Modeling with EISREE PREEIS. and SIMPEIS: Basic applications and programs. Hamptom. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [ Links ]

6. Byrne, B. M. (2008). Testing for multigroup equivalence of a measuring instrument: A walk through the process. Psicothema, 20, 872-882. [ Links ]

7. Cheung, G. W., and Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling. 9(2). 233-255. [ Links ]

8. Cohen, E. G. (1994). Designing groupwork: Strategies for the heterogeneous classroom (2nd ed.). New York: Teachers College Press. [ Links ]

9. Curran, P. J., West, S. G., and Finch, J. F. (1996). The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 1(1). 16-38. [ Links ]

10. Damon, W. (1984). Peer education: The untapped potential. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 5, 331-343. [ Links ]

11. Deutsch, M. (1949). A theory of cooperation and competition. Human Relations, 2, 129-152. [ Links ]

12. Dewey, J. (1915). The school and society. Chicago. IL: The University of Chicago Press. [ Links ]

13. Escartí, A., Pascual. C., y Gutiérrez. M. (2011). Propiedades psicométricas de la versión española del Cuestionario de responsabilidad personal y social en contextos de educación física. Revista de Psicología del Deporte, 20(1), 119-130. [ Links ]

14. Fernández-Rio, J., Sanz, N., Fernández-Cando, J., and Santos. L. (2017). Assessing the long-term effects of cooperative learning on students' motivation. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 22(1), 89-105 doi: 10.1080/17408989.2015.1123238. [ Links ]

15. Fornell, C., and Larcker, D. (1981). Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39-50. [ Links ]

16. García, M. M., González, I., y Mérida, R. (2012). Validación del cuestionario ACOES. Análisis del trabajo cooperativo en Educación Superior. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 30(1), 87-109. [ Links ]

17. Gillies, R. M. (2014). Developments in Cooperative Learning: Review of research. Anales de Psicología, 30(3), 792-801. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.3.201191. [ Links ]

18. Hair, J., Black, B., Babin, B., Anderson, R., and Tatham, R (2006). Multivariate Data Analysis (6th edition). Upper Saddle River. NJ: Prentice-Hall. [ Links ]

19. Hernández-Nieto, R. A. (2002). Contributions to Statistical Analysis. Mérida: Universidad de Los Andes. [ Links ]

20. Hijzen, D., Boekaerts, M., and Vedder, P. (2006). The relationship between the quality of cooperative learning, students' goal preferences, and perceptions of contextual factors in the classroom. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 47, 9-21. [ Links ]

21. Howe, C. (2013). Optimizing small group discourse in classrooms: Effective practices and theoretical constraints. International Journal of Educational Research, 63, 107-115. [ Links ]

22. Ibarra, Ma S., y Rodríguez. G. (2007). El trabajo colaborativo en las aulas universitarias: Reflexiones desde la autoevaluación. Revista de Educación, 344, 355-375. [ Links ]

23. Johnson, D. W., and Johnson, R. T (1983). Social interdependence and perceives academic and personal support in the classroom. The Journal of Psychology, 120, 77-82. [ Links ]

24. Johnson, D. W., and Johnson, R T (1991). Earning together and alone. Boston. MA: Allyn and Bacon. [ Links ]

25. Johnson. D. W., and Johnson, R T. (2014). Cooperative Learning in 21st Century. Anales de Psicología, 30(3), 841-851. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.3.201241. [ Links ]

26. Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., and Holubec, E. J. (2013). Cooperation in the Classroom (9th ed.). Edina. MN: Interaction Book Company. [ Links ]

27. Kagan, S. (1992). Cooperative learning. San Juan Capistrano. CA: Kagan Cooperative Learning. [ Links ]

28. Kyndt, E., Raes, E., Lismont, B., Tummers, F., Cascallar, E., and Dochy, F. (2013). A meta-analysis of the effects of face-to-face cooperative learning. Do recent studies falsify or verify earlier findings? Educational Research Review, 10, 133-149. [ Links ]

29. León del Barco, B., Mendo, S., Felipe-Castaño, E., Polo del Río, Ma. I., and Fajardo-Bullón, F. (2017). Team Potency and Cooperative Learning in the University Setting//Potencia de equipo y aprendizaje cooperativo en el ámbito universitario. Journal of Psychodidactics, 22(1), 9-15. DOI: 10.1387/RevPsicodidact.14213. [ Links ]

30. Mardia, K V. (1974). Applications of some measures of multivariate skewness and kurtosis in testing normality and robustness studies. Sankhya: The Indian Journal of Statistics, 36(2), 115-128. [ Links ]

31. Marsh, H.W. (1993). The multidimensional structure of physical fitness: Invariance over gender and age. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 64, 256-273. [ Links ]

32. Melero, M. A., y Fernández, P. (1995). El aprendizaje entre iguales: el estado de la cuestión en Estados Unidos. En P. Fernández & M.A. Melero (Coord.). La interacción social en contextos educativos (pp. 35-98). Madrid: Ed. Siglo XXI. [ Links ]

33. Muñiz, J., Fidalgo, A. M., García-Cueto, E., Martínez, R., y Moreno, R. (2005). Análisis de los ítems. Madrid: La Muralla. [ Links ]

34. Mussio, S. J., and Smith, M. K. (1973). Content validity: A procedural manual. International Personnel Management Association. [ Links ]

35. Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill. [ Links ]

36. Pons, R. Ma, Prieto, Ma. D., Lomeli, C., Bermejo, Ma. R., and Bulut, S. (2014). Cooperative learning in Mathematics: a study on the effects of the parameter of equality on academic performance. Anales de Psicología, 30(3), 832-840. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.3.201231. [ Links ]

37. Pujolás, P. (2009). La calidad en los equipos de aprendizaje cooperativo: algunas consideraciones para el cálculo del grado de cooperatividad. Revista de Educación, 349, 225-239. [ Links ]

38. Rial, A., Varela, J., Abalo, J., & Lévy, J. P. (2006). El análisis factorial confirmatorio. En J. P. Lévy y J. Varela. (Eds.). Modelización con Estructuras de Covarianzas en Ciencias Sociales (pp. 119-144). Madrid: Netlibro. [ Links ]

39. Satorra, A., and Bentler, P. M. (1994). Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In A. von Eye & C.C. Clogg (Eds.). Latent variables analysis: Applications for developmental research (pp. 399-419). Thousand Oaks. CA: Sage. [ Links ]

40. Sharan, Y. (2014). Learning to cooperate for cooperative learning. Anales de Psicología, 30(3), 802-807. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.3.201211. [ Links ]

41. Schunk, D. (2012). Learning theories: An educational perspective (6th ed.). Boston: Allyn y Bacon. [ Links ]

42. Slavin, R. E. (1995). Cooperative learning: Theory. research. and practice (2nd ed.). Boston: Allyn y Bacon. [ Links ]

43. Slavin, R. E. (2014). Cooperative Learning and Academic Achievement: Why Does Groupwork Work? Anales de Psicología, 30(3), 785-791. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.3.201201. [ Links ]

44. Steiger, J. H. (1990). Structural model evaluation and modification: An interval estimation approach. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 25(2), 173-180. [ Links ]

45. Veenman, S., Benthum, N., Bootsma, D., Dieren, J., and Kemp, N. (2002). Cooperative learning and teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18(1), 87-103. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00052-X. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Javier Fernández-Río.

C/ Aniceto Sela s/n,

despacho 219.

33005 Oviedo - Asturias (Spain).

E-mail: javier.rio@uniovi.es

Article received: 15-02-2016

revised: 03-06-2016

accepted: 06-06-2016