Introduction

In 1971, the medical sociologist Aaron Antonovsky presented the findings of a study1 he conducted on a group of women who had survived Nazi concentration camps. He found that some of these women, despite having suffered stressful situations, had maintained good physical and mental health. Antonovsky was interested in the factors that helped these women to sustain good health, an approach which led him to develop what is today known as salutogenic theory. 2,3

One of his major contributions was to introduce this theoretical framework as a new paradigm of positive health, in contrast to the pathogenic approach. This theoretical framework supports practices aimed at promoting the enhancement and better use of individual and collective resources to improve population health and well-being.4

Antonovsky was one of the first authors to develop an approach which allows studying and quantifying positive protective health factors and their impact on the population. His theories, despite having been applied to more individual approaches with the development of concepts such as sense of coherence (SOC) or generalized resistance resources (GRRs), have also influenced other fields aimed at population-wide approaches.5 Antonovsky introduced the salutogenic concept of SOC as a specific way of viewing life as comprehensible, manageable and meaningful.6) On the other hand, GRRs could be considered as those elements related to the material, biological, psychological and social means that would make it easier for people to perceive life as comprehensible, manageable and meaningful. GRRs would thus act as a kind of health asset that could help improving or maintaining the health of the individuals and the communities in which they live. They act on the SOC and constitute one of the main elements of our study.

Based on this theoretical proposal to carry out the development of possible empirical applications, some authors7 propose that salutogenic interventions should be designed to enable communities to create shared life visions and to be part of decision making (meaningfulness); develop shared mental models about the change process and desired outcomes (comprehensibility); enable communities to identify life demands (e.g., stressors, challenges) and GRRs that need to be balanced (manageability) as well as life opportunities (e.g., assets, learning situations) that stimulate health development.

Other authors have developed theoretical models to implement the salutogenic paradigm in different sectors, such as schools,8 communities or neighbourhoods,5 health systems,9 or within different population groups such as children10 or persons with chronic diseases.11 Some interventions8 have proposed new ways of studying population health by incorporating a positive view of health, an assets orientation, emphasizing both the individual level -by measuring the SOC- and the social or community levels by researching concepts like social capital.

In 2006, Eriksson and Lindström12 carried out a systematic review of 471 papers to study the relation between perceived health and SOC. They found that the stronger the SOC, the better the perceived health. A study recently conducted in Spain13 based on tracking periods over 8, 12 and 20 years, revealed links between perceived health and mortality. The SOC was found to be indirectly associated to a lower mortality rate. In a more social dimension, Holt-Lunstad14 performed a meta-analysis of 148 papers and observed that people with stronger social networks had a 50% increased likelihood of survival, even after adjusting for risk factors. This means that individuals with a stronger SOC or living in communities with greater social capital have better health outcomes.

Despite the numerous empirical applications of the salutogenic theory in the field of public health, reviews of salutogenic-based interventions and their effects on population health are limited.

This has resulted in a range of fragmented actions under the salutogenic paradigm that are hard-to-grasp. This may be due, on the one hand, to the heterogeneity of the interventions included within this theoretical model, and on the other, to the difficulty in measuring health outcomes.

Understanding the achievements of interventions based on the salutogenic theory could lead to stronger support for this type of actions in the field of public health and the implementation of health and well-being policies.

The main objective of the present review is to explore the type of interventions developed using salutogenic theoretical concept and the effects on physical morbidity, mortality, mental health, health related quality of life (HRQoL) and subjective well-being.

Method

A scoping review15 was conducted in 2017. Four databases were searched: PubMed, Embase, Web of Science and Scopus, and hand searches through snowballing was performed. We included articles published over the last 10 years (2007/2016), using the following descriptors related to salutogenic models and selected by the authors: (“Evaluation” OR “Program Evaluation” OR “Outcome Assessment”) AND (“Salutogenesis” OR “social capital” OR “health asset” OR “urbanism” OR “sense of coherence” OR “health assets” OR “health assets model” OR “Salutogenic” OR “Salutogenetic” OR “Salutogenic approach” OR “Salutogenic model”) AND (“Mortality” OR “Morbidity” OR “Quality of life” OR “life expectancy” OR “Mental Health”).

This search strategy was adopted to find papers related to salutogenic theory with an asset-based approach. The final search strategy needed to be kept broad in order to capture all available information with an asset-based approach at individual (SOC) and community level (social capital, urbanism).

We included original articles, reviews, descriptive studies, quasi-experimental and clinical trial articles written in English, French and Spanish. We only took into account interventions that reported evaluations of health outcomes (morbidity, mortality, mental health and/or quality of life). We excluded editorials, letters to the editor, descriptions of experiences without assessments of results, or theoretical dissertations. No other restriction was made. The database search was carried out in 2017. After removing duplicates, two researchers independently screened the abstracts to identify those which met the eligibility criteria. A random sample of 38 papers was selected to assess the level of agreement between the researchers regarding the classification and extraction of information: a high level of consistency was found (kappa index = 86.4%).

The following information was extracted from each of the original selected articles: authors, year of publication, study design,16 country, objective, population, duration, variables, results, adverse effects, limitations and biases as presented by the authors themselves.

After an initial reading to become familiar with the contents, common characteristics regarding the focus of interventions and the target population were identified grouping them into four larger groups:

Individual interventions: encompassing different studies where the intervention was centred on individuals, fundamentally carried out through different psychotherapeutic treatments and with the purpose of modifying cognitive or behavioural aspects.

Group interventions: interventions in groups of people, sharing a similar health issue tackled through the intervention. The purpose of these interventions is, usually, the modification of cognitive or behavioural aspects.

Mixed interventions: interventions combining individual and group approaches.

Intersectoral interventions: interventions aimed at groups or communities to intervene within the environment in which the health problems take place and develop. These interventions include a minimum of two sectoral areas (urbanism, social services, education, health system).

The extracted information was presented by grouping the articles according to the type of intervention and describing the effects relating to health outcomes. To synthesize the information, we performed a descriptive statistical analysis, including frequencies and means calculated. To study mean differences, a student t-test was performed.

Results

Main characteristics of the studies

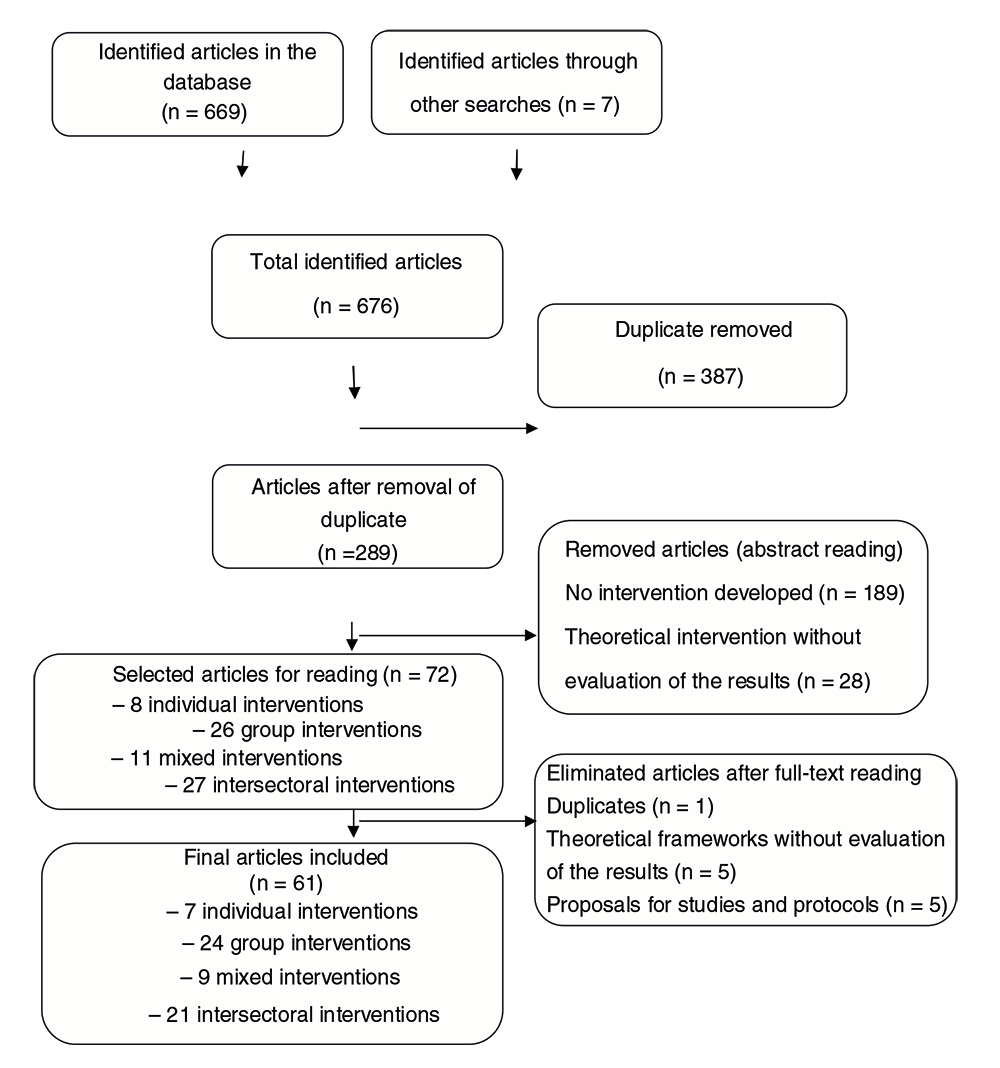

A total of 669 articles were located in the consulted databases distributed as follows: 115 in PubMed, 175 in Web of Science, 164 in Embase, and 215 in Scopus. Complementary papers potentially eligible were included, a search through snowballing was performed, and seven studies were identified (Fig. 1).

After screening titles and abstracts, 72 papers were retrieved full text for further reading. A total of 61 articles fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were finally included in the scoping review. Most part of the studies, 62.29% (38), were published between 2013-2016. The studies included were carried out in 23 countries within the five continents. Were done with women 8.2% (5) of the studies, 3.3% (2) with men, and the remaining 88.5%

(54) with men and women. With regard to the average number of months of the monitoring concerning the studies identified, intersectoral interventions were those with the highest monitoring data (86.6 ± 92.9), followed by the individual interventions (20.3 ± 18.1), the group interventions (16.8 ± 22.9), and finally the mixed interventions (13.53 ± 7.1). The biggest category was that of group interventions (39.34% of the studies), followed by intersectoral interventions (34.42%), mixed interventions (14.75%) and individual interventions (11.47%). The main characteristics are described in Table 1.

Table 1. General characteristic of the studies.

| Type of intervention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual (n = 7) | Group (n = 24) | Mixed (n = 9) | Intersectoral (n = 21) | Total (n = 61) | |

| Year of publication | |||||

| 2007-2009 | 2 (28.57%) | 4 (16.67%) | 3 (33.33%) | 3 (14.29%) | 12 (19.67%) |

| 2010-2012 | - | 3 (12.5%) | 1 (11.11%) | 7 (33.33%) | 11 (18.03%) |

| 2013-2016 | 5 (71.43%) | 17 (70.83%) | 5 (55.56%) | 11 (52.38%) | 38 (62.29%) |

| Design | |||||

| Descriptive (n = 9019a) | - | 4 (16.67%) | - | 7 (33.33%) | 11 (18.03%) |

| Analytic (n = 2129) | 1 (14.29%) | 1 (4.17%) | 2 (22.22%) | 1 (4.76%) | 5 (8.20%) |

| Quasi experimental (n = 15.142) | 2 (28.57%) | 10 (41.67%) | 7 (77.78%) | 6 (28.57%) | 25 (40.98%) |

| RCT (1905) | 4 (57.14%) | 7 (29.17%) | - | 1 (4.76%) | 12 (19.67%) |

| SR/SR (7003b) | - | 1 (4.17%) | - | 4 (19.05%) | 5 (8.20%) |

| Qualitative (n = 53) | - | 1 (4.17%) | - | 2 (9.52%) | 3 (4.92%) |

| Monitoring average (months) | 20.3 ± 18.1 | 16.8 ± 22.9 | 13.53 ± 7.1 | 86.6 ± 92.9 | 39.9 ± 64.2 |

| Total size | n = 1055 | n = 10.730 | n = 11.888 | n = 11.578c | n = 35.251 |

| Sample size | |||||

| < 101 | 4 (57.14%) | 14 (58.33%) | 6 (66.67%) | 6 (28.57%) | 26 (42.62%) |

| 101-500 | 3 (42.86%) | 6 (25%) | 2 (22.22%) | 2 (9.52%) | 14 (22.95%) |

| 501-1000 | - | 3 (12.50%) | - | - | 6 (9.83%) |

| > 1000 | - | 1 (4.17%) | 1 (11.11%) | 4 (19.04%) | 6 (9.83%) |

| No available | - | - | - | 9 (42.85%) | 9 (14.75%) |

RCT: randomized controlled trial; SR/SR: scoping review/systematic review. a 45.4% (5) of the articles did not specify the sample size adopted in the intervention. b 80% (4) of the articles did not specify the sample size adopted in the intervention. c 42.8% (9) of the articles did not specify the sample size adopted in the intervention.

Quasi-experimental designs were used in 40.98% of the papers, notably including community trials and pre-test/post-test studies. The randomized clinical trials represented 19.67% of the studied sample. Only a total of 4.92% of the interventions were analyzed using qualitative research designs. Important differences existed in the design typology depending on the type of interventions.

The most prevalent methodological designs in each type of interventions were randomized controlled trials for individual interventions (57.14%), quasi experimental designs for group (41.67%) and mixed interventions (77.68%), and finally descriptive studies for intersectoral interventions (33.33%).

Type of salutogenic interventions

Table 2 shows the different types of interventions. Most of the individual interventions are focused on health education activities, counselling and/or psychotherapeutic approaches from different approaches (cognitive-behavioural therapy, psychodynamic, occupational therapy).

Table 2. Effects and limitations identified by typology of intervention.

| Individual interventions | Group Interventions | Mixed interventions | Intersectoral interventions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive effects | 71.43% | 87.50% | 100.00% | 80.95% |

| Adverse effects | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Health outcomes improvements | HIV rate22 | Prevalence and morbidity burden27,28 | Functional capacity40 | Life expectancy at birth, life expectancy in good health, and mortality for a variety of reasons: maternal, infantile and famine mortality17 |

| Anxiety-related symptomatology23 | Perceived health29,30 | Pain-related symptomatology40,41 | Perceived well-being and self-rated health17,49 | |

| Eating disorders24 | Well-being and perceived quality of life31-37 | Dream quality40,42,43 | Preventable mortality for diabetes mellitus, influenza, heart disease and infant mortality18 | |

| Perception of quality of life24,25 | Psychopathological symptomatology, anxiety and depression32,39 | HRQoL40-42,44,45 | HRQoL50-53 | |

| Personal satisfaction26 | Stress symptomatology 34 | Kinesophobia40,42 | Mental health54-56 | |

| Psychopathological symptomatologies24,26 | Functional capacity38 | Psychological, physical and social well-being43 | Depressive symptomatology57 | |

| Burnout39 | Physical and mental health44,46-48 | |||

| Type of methodological limitations (identified by authors in their own work) | ||||

| Sample size | 57.14% | 37.50% | 55.56% | 14.29% |

| Generalization results | 28.57% | 29.17% | 0.00% | 28.57% |

| Selection bias | 14.29% | 37.50% | 33.33% | 42.86% |

| Unvalidated tools | 0.00% | 0.00% | 22.22% | 9.52% |

| Confounding variables control | 28.57% | 20.83% | 11.11% | 33.33% |

| Sample loss | 14.29% | 16.67% | 11.11% | 4.76% |

| Equivalent control group | 14.29% | 16.67% | 0.00% | 9.52% |

HIV: human inmmunodeficiency virus; HRQoL: health related quality of life.

Group interventions include health education activities, as well as different types of psychotherapy (cognitive-behavioural, psychodynamic, holistic, community). Unlike individual interventions, they are developed in groups of people sharing a similar health problem.

Mixed interventions incorporate combined actions at individual and group level.

Intersectoral interventions incorporate actions aimed at intervening not only on people and communities, but also within the environment in which the health problems take place. These interventions are carried out with the participation of stakeholders from two or more different background areas (urban renewal programs, social participation, governance...).

Relationship between salutogenic interventions and health outcomes

For each intervention type, a summary of the salutogenic interventions is given, describing the main health outcomes improvements and limitations identified (Table 2).

As can be seen in Table 2, studies in the field of individual salutogenic interventions are developed in relation to physical morbidity (human immunodeficiency virus [HIV]), mental health and perceived quality of life and health. These types of interventions led to a variety of health outcomes improvements, notably the following: a decrease in HIV rates, a reduction in anxiety-related symptomatology, an increase in perception of quality of life, higher personal satisfaction, a reduction in psychopathological symptomatology, and a drop in eating disorders.

Group interventions targeted different health topics, ranging from the management of chronic diseases, to mental health and subjective well-being. Additionally, some papers examined different social dimensions relating to social trust, social capital and social compromise. In these types of interventions, improvements were identified in different fields of study, such as: a reduction in disease prevalence and morbidity burden, improvements in perceived health, greater well-being and perceived quality of life, a decrease in psychopathological symptomatology, as well as other symptoms relating to anxiety and depression, improved functional capacity, lower burnout and a reduction in stress symptomatology. The selected mixed interventions presented a wide range of topics linked to management of chronic pain, functional capacity improvement, HRQoL, drug consumption, and psychosomatic disorders. These studies identified improvements in different fields of action linked to a reduction in pain-related symptomatology, a drop in insomnia and an increase in dream quality, improvements in HRQoL, an increase of the functional capacity, a decrease of kinesophobia, higher psychological, physical and social well-being, and greater physical and mental health.

The selected studies in intersectoral interventions identified were focused in urban development, the implementation of community interventions, self-care programmes, social prescription, development of public policies and basic services, governance and multisectorality, health behaviours approach, social capital, and mental health. These interventions led to improvements in HRQoL, an increase in perceived well-being and self-rated health, greater mental health, a reduction in depressive symptomatology, a decrease in preventable mortality for diabetes mellitus, influenza, heart disease and infant mortality.

Positive health outcomes and methodological limitations of the salutogenic interventions

There were important differences between the positive health outcomes depending on the typology of intervention, but most of the studies (85.25%) showed positive findings. None of the studies reported adverse effects.

Two of the identified articles developed by Ciccone et al. in 2014,17 and Mays et al. in 2016,18 showed a relation between interventions and mortality reduction. Both studies are intersectoral interventions and they were based on the influence of health policies and governance mechanisms and their impact on health.

The study of Mays et al.18 aimed to measure the extent and nature of multisector contributions to population health activities and how these contributions affect community mortality rates. The study of Ciccone et al.17 about governance mechanisms and health outcomes in low and middle income countries suggest that governance mechanism may influence health outcomes in different settings (life expectancy at birth, life expectancy in good health, as well as reduced mortality).

The mixed interventions are those that present the highest degree of positive effects (100%). The positive effects identified in this review did not take into account the methodological design of each study, which would have had an impact on the findings discussed. Significant methodological limitations were found by the authors of the papers (75.41%). The most common biases identified were associated to participant selection bias in 36% of the cases, followed by the sample size (34.43%). To a lesser extent, the absence of a control group or a lack of equivalence in the control group were reported as potential limitations (11.48%), important sample losses occurred during the implementation of the studies (11.48%) and in 6.56% of the studies the use of non-validated tools was discussed as a potential limitation.

Conclusions

This research has offered an overview of interventions adopting a salutogenic framework, from the individual to the intersectoral level, synthesizing the variety of actions which can be included under this paradigm, and describing their impacts on health and their study limitations.

Recently, the number of studies carried out in this field of study has significantly increased. Most of the studies described positive effects on health, especially in the field of mental health. Grouped, mixed or intersectoral interventions showed better health outcomes than de individual ones. This may be due to the incorporation of a more collective approach to the problem. Such an approach may enhance social support and social networks, thus addressing a broader range of health determinants and potentially increasing better health outcomes.14 The majority of positive effects are related to perceived quality of life and health, followed by mental health and physical morbidity reduction.

Most of the interventions reflect the salutogenic theories only partially, through incorporating some of their elements, such as SOC or GRRs which were the focus of this review. A systemic salutogenic approach, that seeks to act not only on the individuals but also on the communities and contexts in which they live, could have an expanded effect in terms of improving the health outcomes of the population, as seen in the positive impact associated with some of the intersectoral interventions.17,18 However, these positive results could depend on the fact that longer periods of monitoring are present in intersectoral actions Despite the fact that different authors1-3,19,20 have tried to define the salutogenic theory it is necessary to reach a consensus that defines the minimal characteristics that a salutogenic intervention should follow and validate a tool which evaluates the salutogenic contents of the interventions. Reviews of salutogenicbased interventions and their effects on population health are limited.

Our research has some methodological limitations which can affect the interpretation as well as the generalization of the results. Some of the terms used such as health assets, do not have normalized descriptors in the databases, thus affecting the sensitivity of the search process.21 The search strategy was limited at identifying articles related to the application of the salutogenic paradigm in health interventions, thus eventually excluding other studies adopting the paradigm in other sectors and studies using this approach without qualifying them as salutogenic. On the other hand, the use of standardized descriptors in the search strategy of our study has facilitated the inclusion of papers that, in other contexts, would not meet the minimum criteria to consider them as salutogenic.

In some cases, data extraction was challenging, since not all studies provided detailed information on their methodological design. In some studies, the dependent and independent variables were not clearly identified and the authors of the present work had to classify them according to the available information.

As for the limitation identified in the included papers these studies need to be conducted with improved monitoring and evaluation designs. Future research should centre on developing a typology of salutogenic interventions, potential beneficiaries and effects on health. Tools as well as indicators are also necessary to better understand the impact of those interventions on the population health.

Methodological rigour must be established; studies should be carried out under stricter conditions which allow confirming the efficacy of interventions. Furthermore, additional tracking should be encouraged to account for the medium and long-term effects of salutogenic programmes.

Qualitative research in this area can support in the understanding of the mechanisms that explain the health improvement, including the range of outcomes identified by the population itself. Further research may also need to account for a potential publication bias in the sense of a tendency to publish only articles with positive results which could explain the high rate of positive effects identified in the studies included in this scoping review.

The lack of clinical trials, the wide variety of methodological designs and the scientific validity of some of the interventions could explain the difficulties for the practical implementation of this theoretical model. Nonetheless, most of the findings of the studies included in this review seem to suggest that salutogenic interventions can achieve positive effects and that could have numerous empirical applications.

We hope the results obtained in this review will be useful for other researchers, especially in terms of understanding the salutogenic theoretical concept and the range of interventions types and health outcomes that it can achieved as described by the authors in the scientific literature.