Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.104 no.1 Madrid ene. 2012

https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S1130-01082012000100003

Diagnostic incidence of the presence of positive HBsAg: epidemiologic, clinical, and virological characteristics

Incidencia diagnóstica de AgHBs positivo. Características epidemiológicas, clínicas y virológicas

Elvira Poves Martínez1, David del Pozo Prieto1, Belén Costero Pastor1, Gloria Borrego Rodríguez1, Inmaculada Beceiro Pedroño1, Cecilia Sanz García1, José Ignacio Busteros Buraza2 and M.a Rosa González Palacio3

Departments of 1Digestive Diseases, 2Histopathology, and 3Microbiology. Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias. Alcalá de Henares, Madrid. Spain

ABSTRACT

Objective: to analyze the epidemiological, clinical, and virological characteristics of patients newly diagnosed with active hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection based on the presence of positive hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) in the digestive diseases department of a district hospital.

Patients and methods: we performed a 3-year prospective study in patients newly diagnosed with HBV infection. We analyzed epidemiological, clinical, and virological characteristics, complete HBV markers, quantification of HBV DNA, and infection by hepatitis delta virus. We performed genotyping and resistance testing in patients with a high viral load. Results were obtained for patients who required liver biopsy.

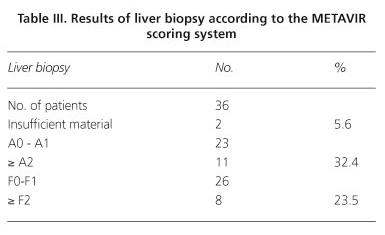

Results: we diagnosed 213 patients (18.8/10,000 inhabitants/year). Men accounted for 61%, and 59% were aged 20 to 40 years. Immigrants accounted for 53% of the population: 46% were from Rumania and 37% from Sub-Saharan African countries. At diagnosis, 2.3% had acute hepatitis (all with jaundice) and 3.3% had cirrhosis with portal hypertension. With the exception of cases of acute hepatitis, positive HBeAg was observed in 9%. Serum transaminase levels were normal in 62.2% of patients, HBV DNA was > 2,000 IU/mL in 33.8%, and delta virus was present in 3.3%. Genotyping and resistance testing were performed in 70 patients: the most common genotype was D, followed by A. Resistance was detected at baseline in only 2 cases: to adefovir in one case and to entecavir in another. Among the 36 biopsies performed, 32.4% showed inflammatory activity ≥ 2, and 23.5% had fibrosis ≥ 2 according to the METAVIR scoring system. According to clinical practice, specific treatment for HBV infection was necessary (any reason) in 17.4% of those diagnosed (3 patients per 100,000 inhabitants/year).

Conclusions: despite prevention and vaccination, HBV infection is a health problem that most commonly affects the immigrant population and men. Serum transaminase levels are normal in 62.2% of patients. The most frequent genotype is D, followed by A, and baseline resistance is scarce.

Key words: HBV. Epidemiology. Diagnostic incidence.

RESUMEN

Objetivo: analizar las características epidemiológicas, clínicas y virológicas de los pacientes que han sido nuevos diagnósticos de infección activa por VHB, por la presencia de AgHBs positivo, en el servicio de Aparato Digestivo de un hospital de área.

Pacientes y métodos: se trata de un estudio prospectivo realizado durante 3 años, en pacientes de nuevo diagnóstico de infección por VHB, donde se han analizado las características epidemiológicas, clínicas, marcadores completos de VHB, cuantificación de DNA-VHB e infección por virus Delta. En los pacientes con alta carga viral se han estudiado genotipos y resistencias. En los pacientes con indicación de biopsias hepáticas sus resultados.

Resultados: se han diagnosticado 213 pacientes, 18,8/10.000 habitantes y año. El 61% son varones, el 59% con edad comprendida entre 20 y 40 años. El 53% corresponde a población inmigrante, 46% procedentes de Rumanía y 37% de países subsaharianos. En el momento del diagnóstico, el 2,3% tenían una hepatitis aguda, todos los casos con ictericia, y el 3,3% una cirrosis hepática con hipertensión portal. El AgHBe positivo, descontando los cuadros de hepatitis aguda, estaba presente en el 9%. Las transaminasas eran normales en el 62,2%, el DNA-VHB en el 33,8% es superior a 2.000 UI/ml y la asociación del virus Delta está presente en el 3,3%. En 70 pacientes se analiza el genotipo y resistencias, siendo el más frecuente el D, seguido del A; solo se han detectado dos resistencias basales, una a adefovir y otro a entecavir. En las 36 biopsias hepáticas realizadas, el 32,4% tenían una actividad inflamatoria mayor o igual a 2, y el 23,5% una fibrosis igual o superior a 2, valorada según la clasificación de METAVIR. El 17,4% de los diagnosticados ha precisado tratamiento específico para el VHB según práctica clínica por algún motivo, lo que ha supuesto iniciar tratamiento a unos 3 pacientes por cada 100.000 habitantes y año.

Conclusión: a pesar de la prevención y vacunación, la infección por VHB es un problema de salud, afecta de forma más frecuente a población inmigrante, varones y cursa en el 62,2% con transaminasas normales. El genotipo más frecuente es el D seguido del A y las resistencias basales son escasas.

Palabras clave: VHB. Epidemiología. Incidencia diagnóstica.

Introduction

Infection by hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a worldwide health problem, although its prevalence, transmission mechanisms, risk population, and natural history differ depending on the geographic region. According to the World Health Organization, approximately 2 billion people have been infected by HBV. More than 300 million of these are chronic carriers, of whom 25% will develop complications such as cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma, which is the cause of death if preventive or specific treatment is not administered (1,2).

HBV is a member of the hepadnavirus family, whose genome is formed by a small DNA molecule (3). This genome has a 100-fold greater mutation rate than other DNA viruses, as a result of the lack of repair mechanisms during the reverse transcription phase of the viral replication cycle. Consequently, a complex mix of circulating genetic variants evolves during infection, depending on factors such as the immune response and antiviral therapy. Eight distinct genotypes (represented by the letters A to H) have been defined. These genotypes have different geographic distributions and seem to possess characteristics that affect disease course and response to therapy (4,5).

The distribution of infection is universal; however, the prevalence and route of transmission vary with the geographic area. Traditionally, endemicity patterns have been defined as high, intermediate, and low. A high-prevalence area is one in which at least 8% of the population is infected, with a more than 60% probability of presenting active or resolved infection during life. Approximately 45% of the world's population lives in such areas, where infants are often infected through vertical transmission, thus leading to a high frequency of chronic disease. An intermediate-prevalence area is one in which prevalence is between 2 and 7%, with a 20-60% risk of infection during life. These regions account for 43% of the world's population and infection occurs in all age groups. A low-prevalence area is one in which less than 2% of the population is infected. These areas account for 12% of the world's population. The risk of infection is less than 20% and infection occurs mainly in risk groups (6,7).

Spain, like other Mediterranean countries, is considered an intermediate-prevalence area where infection is more common during adolescence and adulthood and the main mechanisms of transmission are family contact, sexual relations, and injecting drug use. Although HBV infection is a notifiable disease, its real prevalence is unknown, and published data are usually from risk groups or specific areas (8-10).

Migratory flow, travel, and globalization are the factors that currently facilitate spread of HBV infection (11), since the population from the highest-prevalence areas has increased the number of HBV-infected patients in our setting. In addition, chronically infected patients have a 15-40% greater risk of progressing to cirrhosis, liver failure, or hepatocellular carcinoma (12).

A specific vaccine against HBV has been available for more than 20 years. Initially, it was made from particles of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) extracted from chronic carriers; since the 1980s, the vaccine has been made from particles obtained using genetic recombination. In Spain, the vaccine was initially used in risk populations, although it is now included in the infant vaccination schedule. Nevertheless, despite the availability of the vaccine, HBV infection remains an important health problem.

We present a descriptive study of the epidemiological, clinical, and virological characteristics of newly diagnosed cases of HBV infection in the Autonomous Community of Madrid, Spain.

Patients and methods

We performed a prospective observational study analyzing the epidemiological, clinical, and virological characteristics of all patients newly diagnosed with active HBV infection. Diagnosis was based on the presence of HBsAg. The study was performed in the Digestive Diseases Department of our institution (Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias, Alcalá de Henares, Madrid, Spain), a district hospital attending patients aged more than 14 years.

The patients attended in the Digestive Diseases Department are referred for study and evaluation of treatment by primary care physicians and other specialists in our hospital. Patients are usually referred with positive HBsAg or for evaluation of liver disease based on increased serum transaminase levels.

Patients were included over a 3-year period (2007-2009), and data were analyzed until December 2010. Our Digestive Diseases Department attends 378,000 inhabitants in a catchment area in which 83% of the population live in an urban environment. The area also has a large immigrant population, mainly from Rumania.

The epidemiologic data analyzed were age, sex, country of birth, and possible routes of transmission. Clinical and laboratory data included alfa-fetoprotein, complete HBV markers, DNA quantification, and delta virus infection based on anti-delta antibody and Deltavirus PCR. In the case of patients with a high viral load -potential candidates for treatment- genotyping was performed and baseline resistance determined. We also analyzed the results of liver biopsy performed until December 2010 in patients in whom it was considered necessary according to habitual clinical practice, that is, viral load greater than 2000 IU/mL for 1 year with serum transaminase levels lower than twice the normal levels. All patients underwent abdominal ultrasound scan.

HBV DNA viral load was determined using the COBAS TaqMan HBV kit (Roche) and a plasma sample. The viral DNA extracted was used for sequencing with the TRUGENE HBV Genotyping Kit (Bayer Diagnostics).

Ultrasound-guided percutaneous liver biopsy was performed using a Menghini 16G needle. Tissue was fixed in 10% formaldehyde for 24-36 hours and embedded in paraffin. Sections (3-5 µm) were taken for histopathology and stained using standard techniques (hematoxylin-eosin, reticulin, Masson trichrome, PAS diastase, and Perls. Specimens were analyzed by size based on portal space count and evaluated using the METAVIR scoring system (13,14).

Results

During the study period (3 years), we diagnosed 213 new HBsAg-positive cases, that is, 71 patients per year or a diagnostic incidence of 18.8 new patients with active infection per 100,000 inhabitants/year.

Men accounted for 61% of the population, and the mean age was 38 ± 12.8 years. By age group, 59% were aged 20 to 40 years, only 4 patients were aged 15-20 years, and 14 patients were aged over 60 years.

Only 47% of the patients were born in Spain, whereas the remaining 53% were immigrants. The countries of origin of the immigrant patients were Rumania (46%), Sub-Saharan Africa (Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone) (37%), Central and South America (6%), Asia (5%), Morocco (4%), and Mauritania and Bulgaria (2%).

In most cases, the route of transmission was difficult to establish, although all patients diagnosed with acute viral hepatitis acquired the infection through sexual relations. In 2% of cases, patients reported having consumed drugs intravenously.

At diagnosis, only 5 patients (2.3%) had acute viral hepatitis (4 Spanish and 1 Rumanian). All patients with acute hepatitis had jaundice and were aged 24 to 48 years; infection did not become chronic in any cases. Seven patients aged 40 to 69 years already had liver cirrhosis with portal hypertension (3 Spanish and 4 Rumanian). No patients had hepatocellular carcinoma at diagnosis, and alfafetoprotein levels were normal. No space-occupying lesions were observed on abdominal ultrasound.

Infection by hepatitis delta virus -based on the presence of anti-delta antibodies and positive PCR-delta findings- was only recorded in 7 patients and was more frequent among immigrants. None of the patients diagnosed with acute hepatitis presented coinfection (Table I).

HBeAg was detected in only 24 patients (11.3%); however, if we exclude patients with acute infection, HBeAg was only present in 9%. The percentage was higher in immigrant patients (11.5%). Eleven patients with positive HBeAg also had a viral load greater than 7 Log.

Transaminases were normal in 66.2% of patients and double the normal value in only 12.2% of patients (Table I).

Viral load was calculated for all patients and was detectable in 15.5% of cases. Viral load was > 2000 IU/mL in 34% of cases; in 15 patients this was >7 Log. In patients diagnosed with liver cirrhosis, viral load was either undetectable or < 2,000 IU/mL.

Viral load was ≤ 2000 IU/mL in 141 patients, of whom 82 (38.5%) also had normal transaminase levels. Three of these patients had already been diagnosed with liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension.

Genotyping was performed in the 70 patients with the highest viral loads. Seven different genotypes were found, the most frequent being D (58%), followed by A. Genotypes B and C were detected in 2 Chinese patients, E and F in patients from Sub-Saharan Africa, and F in 2 Spanish patients (aged 22 and 53 years) (Table II).

Resistance testing was also performed in the 70 patients who underwent genotyping; resistance was found in 2 patients, both of whom had genotype D. One of the patients was Spanish, with possible resistance to entecavir (mutation M250I), and the other was from Sub-Saharan Africa, with resistance to adefovir (mutation I233V).

Liver biopsy was performed without complications in 36 patients. The sample was considered insufficient in 2 cases, as it only had 2 and 3 portal spaces, respectively. In the remaining 34 patients, the mean number of portal spaces per sample was 9.79. The presence of inflammatory activity and fibrosis is shown in table III.

At December 31, 2010, 17.4% of patients diagnosed required specific treatment for HBV infection (any reason) according to habitual clinical practice; in other words, treatment was initiated in 3 patients per 100,000 inhabi-tants/year. Specific treatment was administered in 37 patients (in 7 patients with liver cirrhosis, in 26 patients with chronic hepatitis, and as prophylaxis in 4 patients who needed immunosuppressive treatment).

Discussion

Although HBV infection (ICD-9 CM 070.3) is a notifiable disease in Spain, no real or overall data are available on its prevalence. Despite prevention campaigns and implementation of vaccination, HBV infection is common in our setting (71 new patients per year). Therefore, we determined the characteristics of newly diagnosed patients, taking into account that these data do not enable us to define prevalence in the region, although they do reveal the importance of the HBV infection as a health problem.

In 2002, Solà et al. performed a population-based study (2,194 individuals from different areas of Catalonia stratified according to the official census) (8) using serology samples to determine the prevalence and serological characteristics of HBV in aliquots of serum from a random sample. Prevalence was 1.69% and only 12.1% of the HBV-positive patients had detectable HBV DNA. Transaminase levels were normal in most patients (70.9%).

The effect of immigration on the epidemiology of HBV infection has been described in several studies (15-18); for example, among pregnant women in Madrid, the prevalence of positive anti-HBc was statistically significantly higher in Asians (27.6%) and Africans (18.8%) than in Spaniards (3.7%), Europeans (3.3%), and Americans (4.6%) (19).

According to the official census of foreign residents (January 2008), the Autonomous Community of Madrid had 1,060,600 foreign residents, that is, 16.62% of the local population. As for origin, 47% were from Latin America, 35.13% from Europe, 8% from North Africa, 6% from Asia, and 4% from Sub-Saharan Africa. Most immigrants were from Rumania, followed by Ecuador (20). Although the above-mentioned study shows that immigrants account for 16.6% of the population of the Community of Madrid, most patients diagnosed (53%) are immigrants, mainly Rumanians and Sub-Saharan Africans.

Despite the availability of vaccination and information for the general population on routes of transmission in adults, acute HBV hepatitis continues to be diagnosed. Moreover, cases that progress without jaundice are normally underdiagnosed. Although our study was performed in a digestive diseases clinic, we diagnosed 5 cases in men; most were Spanish-born and all had jaundice.

We found that transaminases were normal in 66.2% of patients, which is consistent with the findings of other authors (8). Therefore, in daily clinical practice, not all carriers of HBV are diagnosed. We also found normal transaminase levels in some of the patients with increased HBV DNA (> 2,000 IU/mL) and in all the patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension; therefore, primary care physicians should be made aware that, in high-risk groups, mainly the immigrant population, HBV testing is advisable regardless of the presence of high transaminase levels.

In Spain, chronic HBV infection is associated with a low presence of HBeAg. In a study of 182 patients with chronic HBV hepatitis, only 7% had positive HBeAg (21), and in another study performed in Almeria among immigrants from Sub-Saharan Africa, only 4.1% of the 137 chronically infected patients were HBeAg-positive (22). Nine percent of our chronically infected patients were HBeAg-positive.

The association with the Delta virus should always be evaluated, as there are 2 potential forms of Delta virus infection: coinfection, which carries a greater risk of fulminant hepatitis, and superinfection in patients previously infected by HBV, most of whom progress to a more severe form of the disease than that produced by HBV alone and with a faster course toward cirrhosis and liver decompensation (although chronic Delta virus infection can be benign). Therefore, association of the Delta virus points to a more severe prognosis (23,24). Approximately 2.5% of infected patients have associated Delta virus infection, although the frequency of this finding may be higher in endemic areas (25). We found that Delta virus infection was present in 3.3% of patients and that the frequency was greater in immigrant patients (Rumanians and Sub-Saharan Africans).

Undetectable viral load was only present in 15.5% of patients, a figure that is lower than those published elsewhere (8); however, the technique used in our study is very sensitive and enables HBV DNA to be detected to 12 IU/mL, thus considerably increasing the figures for detectable HBV DNA.

Eight genotypes have been defined. These differ in terms of amino acid insertions or deletions, leading to a divergence of 8% in the full sequence and thus creating a difference in variability and replication, as well as in sensitivity to drugs. The genotypes were found in different geographic populations. In Spain, genotypes A and D are the most frequent (26), in Asia B and C are the most frequent, in Africa E is the most frequent, and in South America F and H are the most frequent (27,28). Given the geographic diversity of the population in our study, we found all the genotypes except H. Genotype D was clearly the most common, followed by A; however, as expected, we found genotypes B and C in Asian patients and E in Sub-Saharan African patients. Migratory movements mean that we are finding this mix of genotypes with increasing frequency.

The high replication rate of HBV and associated errors leads to daily point mutations in individuals with active replication. Therefore, HBV-infected individuals have a mix of viruses, some of which carry mutations leading to antiretroviral resistance, thus explaining why we do not generally detect resistance using genotyping before treatment; however, these mutations can appear quickly after exposure to therapy. The rate of selection of resistance mutations depends on viral load before treatment, the speed of viral suppression, the duration of treatment, and previous exposure to nucleos(t)ides (29,30). A retrospective study was published in 2007 (31) to determine the prevalence of HBV variants associated with resistance to entecavir in treatment-naïve patients before and after treatment with lamivudine. The population comprised 111 patients, of whom 3 cases (2.7%) showed resistance to entecavir before starting treatment with lamivudine; in our study, 2.8% of patients had genotypic resistance before starting antiviral therapy.

In chronically infected patients, the indication for treatment is based on the combination of 3 criteria: HBV DNA > 2,000 IU/mL, transaminase levels above normal, or presence of A2 or F2 in the liver biopsy according to the metavir score (32,33). In our study, liver biopsy was sometimes necessary before deciding on treatment in patients with increased HBV DNA for more than 1 year and no increased transaminase levels; in a considerable number the information provided helped us tailor therapy. Nevertheless, some authors recommend carrying out a liver biopsy to evaluate tissue damage when transaminases are elevated, irrespective of viral load (34).

Although prevention campaigns have been developed in recent years and infant vaccination has been implemented in risk groups, HBV infection is an important health problem, and we continue to diagnose new cases, especially in immigrants and individuals aged 20 to 40 years. Chronic infection often progresses with normal transaminase levels; therefore, it is important to increase awareness of this infection among primary care physicians, so that they can detect HBsAg-positive patients, especially in risk groups such as immigrants from endemic areas, intravenous drug users, individuals with sexual risk practices, patients undergoing multiple transfusions, patients undergoing dialysis, and prison inmates and those in closed centers, as well as in shelters and in certain risk occupations (e.g., health professionals, firemen, prison staff) (15,35). HBsAg-positive patients should be identified so that they can receive instruction on preventive measures, undergo clinical assessment, and receive treatment, if necessary. Combined with vaccination, this approach will enable us to control and possibly eradicate the infection in the future.

References

1. Alter MJ. Epidemiology and prevention of hepatitis B. Semin Liver Dis 2003;23:39-46. [ Links ]

2. Margolis HS, Coleman PJ, Brown RE, Mast EE, Sheingold SH, Arevalo JA. Prevention of hepatitis B virus transmission by inmunization: an economic analysis of current recommendations. JAMA 1995;264:1202-8. [ Links ]

3. Seeger C, Mason WS. Hepatitis B virus biology. Microbiol and Mol Biol Rev 2000;64:51-68. [ Links ]

4. Bartholomeusz A, Schaefer S. Hepatitis B virus genotypes: comparison of genotyping methods. Rev Med Virol 2004;14:3-16. [ Links ]

5. Wai CT, Fontana RJ. Clinical significance of hepatitis B virus genotypes, variants and mutants. Cli Liver Dis 2004;8:321-52. [ Links ]

6. Carey WD. The prevalence and natural history of hepatitis B in the 21st century. Cleve Clin J Med 2009;76(Supl. 3):S2-5. [ Links ]

7. Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 2007;45:507-39. [ Links ]

8. Solà R, Cruz de Castro E, Hombrados M, Planas R, Coll S, Jardí R, et al. Prevalencia de la hepatitis B y C en diversas comarcas de Cataluña: estudio transversal. Med Clin (Barc) 2002;22;119:90-5. [ Links ]

9. Alamillos Ortega P, Failde Martínez I. Prevalencia de marcadores serológicos de la hepatitis B en trabajadores hospitalarios y de atención primaria del área de Jerez (Cádiz). Aten Primaria 1999;23:212-7. [ Links ]

10. Torella Ramos A, Hernández Aguado I, Santos Rubio C, Fernández García de la Hera M, Avino Rico MJ. Determinaciones de prevalencia de la infección por el virus de la hepatitis B en drogadictos por vía parenteral. Rev Clin Esp 1993;193:457-9. [ Links ]

11. Lavanchy D. Hepatitis B virus epidemiology, disease burden, treatment, and curren and emerging prevention and control measures. J Viral Hepat 2004;11:97-107. [ Links ]

12. Willians R. Global challenges in liver disease. Hepatology 2006;44:521-6. [ Links ]

13. The METAVIR Cooperative Study Group. Intraobserver and interobserver variations in liver biopsy interpretation in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 1994;1:15-20. [ Links ]

14. Bedossa P, Poynard T. An algorithm for the grading of activity in chronic hepatitis C. The metavir Cooperative Study Group. Hepatology 1996;24:2189-93. [ Links ]

15. Valerio L, Barro S, Pérez B, Roca C, Fernández J, Solsona L, et al. Seroprevalence of chronic viral hepatitis markers in 791 recent immigrants in Catalonia, Spain. Screening and vaccination against hepatitis B recommendations. Rev Clin Esp 2008;208:426-31. [ Links ]

16. Ramos JM, Pastor C, Masia MM, Cascales E, Royo G, Gutiérrez-Rodero F. Health in the immigrant population: prevalence of latent tuberculosis, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, human immunodeficiency virus and syphilis infection. Enferm Infect Microbiol Clin 2003;21:540-2. [ Links ]

17. Juncosa T, Fumadó V, Martín J, Palacin E. Virus de la hepatitis B en niños adoptados o inmigrantes en Cataluña. Med Clin (Barc) 2005; 124:196-7. [ Links ]

18. Salleras L, Domínguez A, Bruguera M, Plans P, Espuñes J, Costa J, et al. Seroepidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection in pregnant women in Catalonia (Spain). J Clin Virol 2009;44:329-32. [ Links ]

19. Gutiérrez M, Tajada P, Álvarez A, de Julián R, Baquero M, Soriano V, et al. Prevalence of HIV-1 non-B subtypes, syphilis, HTLV, and hepatitis B and C viruses among immigrant sex workers in Madrid, Spain. J Med Virol 2004;74:521-7. [ Links ]

20. Informe de inmigración de la Comunidad de Madrid. Observatorio de inmigración-Centro de estudios y datos de la Consejería de Inmigración y Cooperación de la Comunidad de Madrid. Enero 2008. Disponible en: http://www.madrid.org [ Links ]

21. Jadí R, Rodríguez F, Buti M, Costa X, Valdes A, Allende H, et al. Mutations in the Basic core promoted region of hepatitis B virus. Relations with precore variants and HVB genotypes in a Spanish population of HVB carrier. J Hepatol 2004;40:507-14. [ Links ]

22. Salas J, Vázquez J, Cabezas T, Lozano Ab, Cabeza. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in Sub-Saharan immigrants in Almeria (Spain). Enfem Infecc Microbiol Clin 2011;29:121-3. [ Links ]

23. Shih HH, Jeng KS, Syu WJ, Huang YH, Su CW, Peng WL, et al. Hepatitis B surface levels and sequences of natural hepatitis B virus variants influence the assembly and secretion of hepatitis D virus. J Virol 2008;82:2250-64. [ Links ]

24. Fattovich G, Giustina G, Christensen M, Pantalena M, Zagni I, Realdi G, et al. Influence of hepatitis delta virus infection on morbility and mortality in compensated cirrhosis type B. Gut 2000;46:420-6. [ Links ]

25. Taylor J. Hepatitis Delta virus. Virology 2006;344:71-6. [ Links ]

26. Sánchez Tapias JM, Costa J, Mas A, Bruguera M, Rodes J. Influence of hepatitis B virus genotype on the long-ter outcome of chonic B in western patients. Gastroenterology 2002;123:1848-56. [ Links ]

27. Kidd-Ljunggren K, Miyakawa Y, Kidd AH. Genetic variability in hepatitis B virases. J Gen Virol 2002;83:1267-80. [ Links ]

28. Buti M. Genotipos de virus de la hepatitis B. Gastroenterol Hepatol 2003;26:260-2. [ Links ]

29. Bartholomeusz A, Locarnini S. Antiviral drug resistence: clinical consequences and molecular aspects. Semin Liver Dis 2006;26:162-70. [ Links ]

30. Zoulim F, Locarnini S. Hepatitis B virus resistance to nucleos(t)ide analogues. Gastroenterology 2009;137:1593-608. [ Links ]

31. Jardi R, Rodriguez-Frias F, Schaper M, Ruiz G, Elefsiniotis I, Esteban R, et al. Hepatitis B virus polymerase variants associated with entecavir drug resistance in treatment-naive patients. J Viral Hepat 2007;14:835-40. [ Links ]

32. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol 2009;50:227-42. [ Links ]

33. Salmerón J. Is liver biopsy necessary to indicate antiviral therapy in patients with chronic HBV infection? Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2010;102: 515-8. [ Links ]

34. Molina-Pérez E, Castroagudín JF, Aguilera-Guirao A, Otero-Antón E, Tomé-Martínez-de-Rituerto S, Mera-Calviño J, et al. Viral and host factors related with histopathologic activity in patients with chronic hepatitis B and moderate or intermittently elevated alanine aminotransferase levels. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2010;102:519-25. [ Links ]

35. Diago M. Epidemiología de la infección por virus por virus de la hepatitis B. En: Balanzó J, Enriquez J, editores. Hepatitis B. Barcelona: ICG Marge; 2007. p. 19-32. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Elvira Poves Martínez.

Department of Digestive Diseases.

Hospital Universitario Príncipe de Asturias.

Ctra. de Mero, s/n.

28805 Alcalá de Henares. Madrid, Spain.

e-mail: epoves.hupa@salud.madrid.org

Received: 18-05-11.

Accepted: 22-07-11.

texto en

texto en