Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.109 no.4 Madrid abr. 2017

https://dx.doi.org/10.17235/reed.2017.4624/2016

ORIGINAL PAPERS

Usefulness of an intra-gastric balloon before bariatric surgery

Utilidad del balón intragástrico previo a cirugía bariátrica

Cristina Vicente1, Luis R. Rábago2, Alejandro Ortega2, Marisa Arias2 and Jaime Vázquez-Echarri3

Departments of 1Internal Medicine, 2Gastroenterology and 3Surgery. Hospital Severo Ochoa. Leganés, Madrid. Spain

This study was funded by a National Grant from the Spanish Healthcare System: Laín Entralgo Agency, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria FIS, grant PI070682).

ABSTRACT

Introduction: There are only few reports regarding the use of intragastric-balloons (IGB®) to achieve weight loss and subsequently decrease surgical complications. In this study, we try to assess whether presurgery weight loss using IGB decreases the postsurgical mortality after bariatric surgery.

Material and methods: This is a prospective case-control study. We matched 1:1 by gender, age (± 10 y-o) and type of surgery (sleeve resection [LSG] or gastric bypass [LGBP]), matching cases (A) and controls (H, from a historic cohort). Morbidly obese patients with an indication for bariatric surgery were included in the study. Cases (A) were recruited from an ongoing clinical trial, and the controls (H) came from a historic cohort prior to the start of the clinic trial. The presurgical weight loss in group A was reached by IGB combined with diet, versus only diet in group H.

Results: We included 58 patients, 65.5% women, 69% LGBP/31% LSG. The mean age of group A was 42 and 43.4 years old for group H. ASA III of 24.1% group A vs 58.6% group H, p = 0.012. The mean total weight loss (TWL) before surgery was greater in group A (16.2 kg, SD 9.75) than in group H (1.2 kg, SD 6.4), p < 0.0001. The % of EWL before surgery was 23.5 (SD 11.6) in group A vs 2.4 (SD 8) in group H, p < 0.001. Hospital stay was seven days for group A, and eight days for group H, p = 0.285. The rate of unsuccessful IGB treatment to accomplish the scheduled weight loss was 34.5%. The balloon morbidity was 17.2% (6.9% severe). All in all, morbidity (due to bariatric surgery and IGB) was 41% in both groups. Postsurgical morbidity moderate-severe was 20.3% in group A (6.9% severe) and 27.3% in group H (17.2% severe) without statistical significance. One patient died in group H (mortality rate, 3.44%).

Conclusion: Preoperative IGB treatment in morbid obesity has not been found to be effective at decreasing postsurgical morbidity LSG and LGBP, despite the fact that it acheives a greater weight loss than diet and exercise.

Key words: Bariatric surgery. Preoperative intragastric balloon. Postsurgical complications. Preoperative weight loss.

RESUMEN

Introducción: existen pocos estudios que analicen la utilidad del balón intragástrico (BIG) preoperatorio para disminuir la morbilidad relacionada con la cirugía bariátrica. En este estudio evaluamos si el adelgazamiento prequirúrgico mediante BIG disminuye la morbimortalidad tras la cirugía de la obesidad mórbida.

Material y métodos: estudio caso-control emparejado 1:1 por sexo, edad y cirugía bariátrica (bypass gástrico/gastrectomía vertical). Se incluyeron pacientes con obesidad mórbida candidatos a cirugía bariátrica, siendo los casos A reclutados de un ensayo clínico en marcha y los controles H, pacientes operados previo al inicio del ensayo. El adelgazamiento prequirúrgico en el grupo A fue mediante BIG vs. dieta exclusivamente en H.

Resultados: se incluyen 58 pacientes: 65,5% mujeres, 69% bypass y 31% gastrectomía vertical. La edad fue de 42 años en el grupo A y 43 en el H. Encontramos un 34,5% de fracasos terapéuticos del BIG. ASA III: 24,1% en A vs. 58,6% en H (p = 0,012). La pérdida de peso medio corporal (PPCT) antes de cirugía fue de 16,2 kg (desviación estándar [DE] 9,75) en el grupo A frente a 1,2 kg (DE 6,4) en el grupo H, p < 0,0001. El porcentaje de exceso de pérdida de peso (EPP) antes de la cirugía fue del 23,5% (DE 11,6) en el grupo A vs. 2,4 (DE 8) en el grupo H (p < 0,0001), y el porcentaje de exceso de índice de masa corporal perdida (EPIMC) fue del 34,6% (DE 24) en el grupo A vs. 0,98% (DE 12,4) en el grupo H (p < 0,0001).

La estancia hospitalaria fue de siete días en el A y ocho en el H (p = 0,285). El tratamiento con BIG fracasó en el 34,5% de los pacientes. La morbilidad del BIG fue del 17,2% (6,9% grave). La morbilidad relacionada con la cirugía bariátrica/BIG fue del 41% en ambos grupos (p = 0,687); la morbilidad quirúrgica moderada-grave en el grupo A fue del 20,3% (dos pacientes, 6,9% grave) y del 27,3% en el H (cinco pacientes, 17,2% grave), sin diferencias significativas. Un paciente falleció en el grupo H (3,44%).

Conclusión: el BIG preoperatorio no consigue disminuir la morbilidad postquirúrgica de la cirugía bariátrica, y tampoco la estancia ni la tasa de reoperaciones, sin olvidar su coste, pese a que el BIG consigue mayor adelgazamiento que la dieta y el aumento de actividad física.

Palabras clave: Cirugía bariátrica. Balón intragástrico. Morbilidad postquirúrgica.

Introduction

Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) is an epidemic disease. In Europe, it reaches a frequency of 26% to 31%, and Spain is one of the countries with the highest prevalence: 22.9% (1), representing 7% of the healthcare expenditure in our country on 2009 (2).

Currently, it has been clearly accepted that surgery is the best therapeutic option for morbidly obese patients with a BMI > 40 kg/m2, or a BMI between 35 and 40 kg/m2 with a comorbidity which could be improved via weight loss (3,4). Bariatric surgery will not only allow a person to maintain the weight loss over time, but will also lead to a reduction in comorbidities, and even a reduction in mortality over time (5).

Mortality due to bariatric laparoscopic surgery is low (< 1%) (3,6), and its early morbidity varies between 5 and 23.1% (3,6-10). In obese patients with comorbidities which present a risk to their life, this post-surgical morbidity-mortality can be as high as up to 40% in the period immediately after surgery (7,11).

A 10% loss in body weight (10% TWL) will translate into a reduction of visceral, central and abdominal fat, as well as of liver size (12,13); there will be an improvement in associated comorbidities (4,14) and mortality (15).

To reduce the risk of morbidity due to bariatric surgery, many clinical-surgical units request weight loss as a previous requirement (10).

However, some controversy exists as to whether pre-operative weight loss for bariatric surgery could have an impact on surgical morbidity, or on the long-term evolution of the patient (10,13,16).

There are some observational non-controlled clinical trials (17,18) that have not demonstrated that a pre-surgical weight loss (EWL) will determine differences in post-surgical morbidity or the subsequent evolution of the patient (18,19). However, other retrospective studies have found that a pre-surgical weight loss of 5-10% EWL will have an impact on post-surgical morbidity (9,10,16,20), on the time duration of the surgery (19), on the amount of transfusions, and on the rate of conversions to open surgery (6,21,22). Other authors have found that pre-surgical weight loss is a predictive factor for a higher loss weight during post-surgical evolution (6,17), and would help to select those obese population who would benefit most from bariatric surgery. The IGB in morbid obesity is a temporal treatment given as a second step when the multidisciplinary nutritional treatment fails (23), because it results in greater weight loss compared to conventional diet treatments (24-27), although it is not clear whether it is more effective (28,29).

One of the potential future indications for the intragastric balloon could be its use as a bridge-treatment until bariatric surgery (27), not only in order to achieve weight loss before surgery, decrease comorbidity, ease the surgical technique, and decrease postsurgical morbidity, but also to improve comorbidities, facilitate the surgical technique, potentially reduce any surgical complications, or for use in special populations such as super-obese patients (7). More frequently now in clinical practices and in many surgical units, weight loss is attempted before bariatric surgery using intragastric balloons (IGB) in conjunction with strict diets (27,30). However, this therapeutic approach currently presents a dubious utility. Our study intends to contribute to our experience in the evaluation of IGB before surgery for achieving weight loss, and its impact on post-surgical morbidity. Secondly, we will study the impact on mortality, surgical time spent in the operating room, and the rate of reoperations. Finally, we will study any complications associated with IGBs.

Material and methods

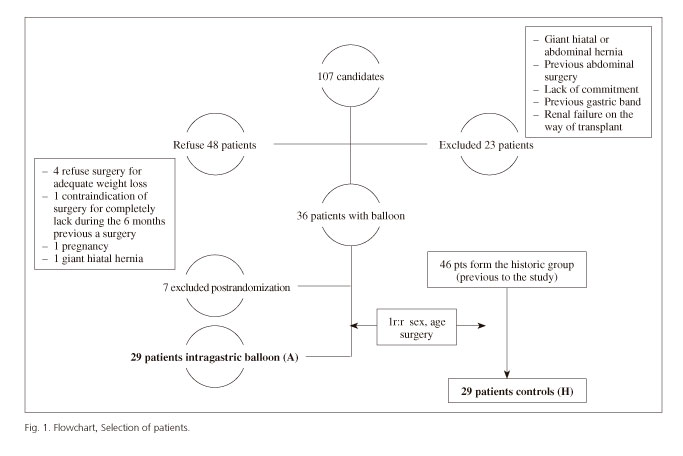

A prospective case-control study, matched 1:1 by gender, type of laparoscopic bariatric surgery (gastric bypass [LGBP] or sleeve gastrectomy [LSG]) and age (+/- 10 years), was performed. The case group (A) included the first 29 patients of a group of 40 from an on-going clinical trial still not completed with a preoperative IGB. The study was funded by a national grant from the Spanish Healthcare System (Agency Lain Entralgo, Instituto de Salud Carlos III, grant FIS PI070682). The control group (H) included 29 patients selected from the historic group of 46 patients with morbid obesity who had undergone laparoscopic surgery prior to the start of patient inclusion in the clinical trial with IGB (Fig. 1).

Morbidly obese patients (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2) with an indication for bariatric surgery, exclusively LSG or LGBP, and with failure of the previous conventional treatment (diet and pharmacological treatment), between 18 and 80-year-old, with the ability to understand the alterations caused by the intervention, and committed to follow the planned strategy were included. We excluded patients with an active peptic ulcer, esophageal/gastric varices, severe disease limiting life expectancy and without any improvement expected by weight loss, decompensated psychiatric illness, moderate or severe esophagitis or hiatal hernia bigger than 3 cm, previous anti-reflux surgery, gastrectomy, or any other type of bariatric surgery or gastric complication associated with previous gastric banding, Crohn's disease, tendency to bleeding and/or current or future need for chronic anticoagulant treatment, contraindication or allergy to IGBs, pregnancy, use of toxic substances or non-idiopathic morbid obesity or treatment with steroids.

The study was conducted at the Hospital Severo Ochoa (HSO) in Leganés (Madrid), which covers a population of 186,066 inhabitants. The Surgery unit has more than ten years of experience in bariatric surgery, conducting about 30 bariatric laparoscopic procedures per year.

The study protocol was approved by the Hospital Ethical and Research Committee and complied with the guidelines of good clinical practice. All patients gave written informed consent.

Procedures

All balloons were placed with conscious sedation, and were endoscopically removed after six months, with patients intubated under general anesthesia. The volume of the balloon was adjusted with a variation from 600 to 700 ml. Balloon placement was conducted under conscious sedation, and its removal was conducted under general anesthesia, and with the patient intubated. Patients were discharged from hospital 3-4 hours after balloon placement, and they were instructed to follow a liquid diet modified during the first week, in order to move on subsequently to the previous solid diet, and to continue treatment with PPIs while the balloon was in place.

All group A patients underwent the same monthly follow-up at the Nutrition Unit during the six months prior to bariatric surgery, with a 1,200 Kcal diet and a recommendation for physical activity; this was the same follow-up conducted for control group H. A minimum interval of 30 days was established between IGB removal and bariatric surgery, in order to try to minimize the yo-yo effect in our patients.

Patient discharge after balloon removal was conducted within some hours (around 3-4 hours), once the patient was completely awake.

The total proportion of weight loss (% TBWL) was calculated, as well as the proportion of excess weight loss (% EWL), and the proportion of BMI excess loss (% EBMIL). The ideal weight estimation was conducted by the Alastrue method (31). Hospital stays were considered as prolonged if they were > 6.5 days for LGBP and > 7 days for LSG. A prolonged time in the Operating Room was defined at > 3 hours.

It has been considered that treatment with an intragastric balloon has failed when a weight loss equal or lower than 10% of the initial total body weight (TBW) has been achieved (32). Total morbidity was considered as the postsurgical morbidity and the morbidity due to IGB.

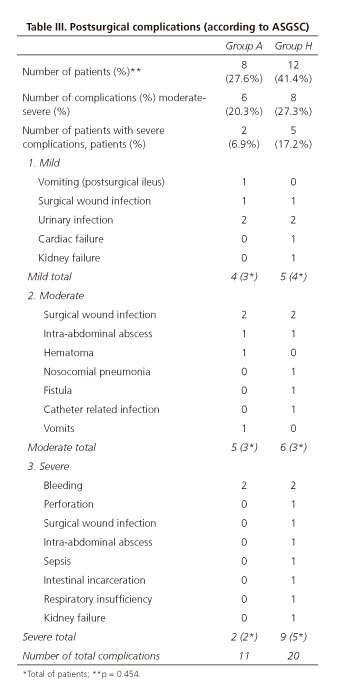

The review and classification of postsurgical complications and their severity was blind, conducted by two members of the group not involved in the study, following the international classification Accordion Severity Grading System of Surgical Complications (ASGSc) (33) (Table III).

The IGB complications were classified as major (balloon migration, intestinal obstruction, Mallory-Weiss syndrome, gastric ulcers, and esophageal laceration) and minor (gastric erosions and abdominal pain and vomiting) (25). Vomiting occurring after IGB placement and during the first few weeks was not considered as a complication. In order to calculate the simple size, and considering the fact that we were unable to find a study similar in design to ours, we took into account the post-surgical morbidity of our historical group of 32% and, expecting a morbidity reduction of 25%, the simple size would be 41 patients in each group.

Quantitative variables are expressed as mean value with the standard deviation (SD) or median with interquartile interval (p25-75), and qualitative variables, as their absolute value and their proportion. A comparison was conducted with x2 for qualitative variables and Mann Whitney's U for quantitative variables. Univariate and multivariate hypothesis contrast was conducted via the Mantel-Haenszel test for paired data. A value of p < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

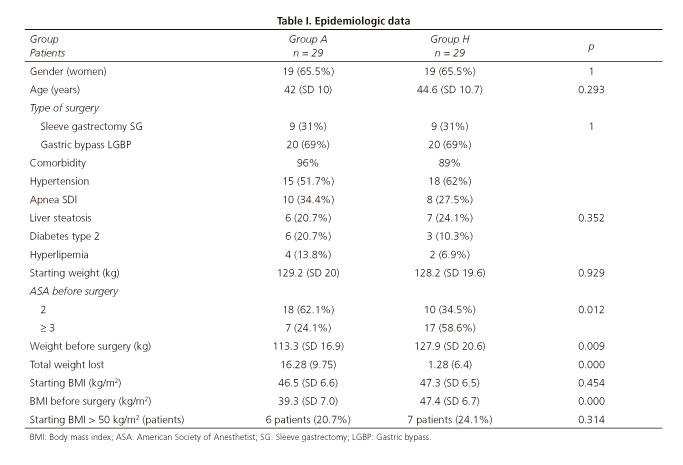

The study included 58 patients, 29 cases and 29 controls. The clinical-epidemiological characteristics of patients are described in table I. There was no difference between groups A and H with regard to body mass index (BMI) and on the median weight at inclusion into the study. The rate of patients ASA III was significantly greater in H (58.6%) vs A (24.1%) (p < 0.012). Ninety-six per cent of patients in group A and 86% in group H had a comorbidity associated with obesity (0.352).

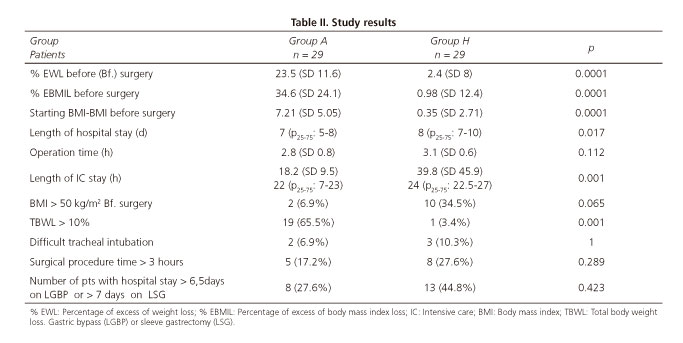

The pre-surgical percentage of EWL in group A was significantly lower than in group H (p < 0.001), thus that there was a mean loss of 16.3 kg TBWL (SD 9.75), with a pre-surgical BMI of 39.3 (SD 7.0) (Table III), an EWL of 23% (SD 11.6) and an EBMIL of 34.6% (SD 24.1) (Table II) vs a TBWL of 1.28 (6.4), a BMI of 47 (SD 6.7), an EWL of 2.4 (SD 8) and an EBMIL of 0.98 (SD 12.4) for the grop H, respectively (p < 0.0001) (Table II).

Nineteen patients (65.5%) in group A lost > 10% (TBWL) of their initial weight vs one (3.4%) in group H (p < 0.001) (Table II). Thirty-seven per cent of patients in group A gained 4 kg (SD 1.8) in the interval between balloon removal and surgery, and only two patients (6.8%) had continued weight loss of three kilos or more after IGB removal.

Patients had their IGB placed during 7.49 months (SD 1.09) with a balloon filled with a volume of fluid of 618.7 ml (SD 54.1). The time between balloon removal and surgery was 56.3 days (SD 58.2). IGB withdrawal before the scheduled time was unnecessary. The removal of the balloon was difficult in 6.9% of patients, but successful. However, 34.5% of IGB (ten patients) did not succeed in reducing their initial body weight by 10%.

Six patients (20.7%) needed emergency treatment for some reason associated with their intragastric balloon, generally in the first week, due to vomiting, dizziness and abdominal pain, which was resolved with symptomatic treatment within less than 24 hours during their stay at the Emergency Unit.

Five patients (17.2%) of group A suffered morbidity associated with their IGB balloon (three mild and two severe [17.2% of total morbidity, 6.89% severe]): three experienced esophagitis diagnosed endoscopically with mild symptoms, and there was one esophagitis case with moderate severity and upper gastrointestinal bleeding (coffee ground vomiting without hemodynamic instability or blood transfusion requirement) which required hospital admission. Another patient had chronic and relapsing functional pyloric stenosis, with vomiting, asthenia, weight loss, and development of a re-feeding syndrome once the IGB was withdrawn and the vomiting disappeared.

Eight patients (27.6%) in group A, and twelve (41.4%) in group H presented 11 and 20 post-surgical complications, respectively (p = 0.454). There were no differences between groups regarding the morbidity considered as severe, or total morbidity (Table III). Total morbidity (postsurgical and IGB morbidity) was the same in both groups 41%.

Postsurgical morbidity that can be considered as relevant from a clinical point of view includes moderate and severe morbidity (according to the ASGSc classification [33]), which was 20.3% (six patients) in group A vs 27.3% (eight patients) in group H (p = 0.388); moderate morbidity was observed in three out of eight patients in group A vs three out of 12 in group H; and severe morbidity was observed in two out of eight patients in group A vs five out of 12 in group H, without statistical differences.

One patient from group H (3.44%) died due to septic shock associated with diffuse peritonitis after suture dehiscence, and no deaths were reported in group A, without significant differences between both groups. Group A had two patients out of 29 with severe postsurgical complications (6.89%) and another two patients (6.89%) with severe IGB complications (upper gastrointestinal bleeding and re-feeding syndrome), while group H had five out of 29 patients (17,2%) with severe postsurgical complications. In the univariante analysis, we did not find any significant differences in morbidity between both groups (Table III), or in hospital stay or in the operating room time (Table II).

There were no differences in the rate of repeat procedures between groups; two patients (6.9%) in each group required a new intervention. We did not find any differences in the rate of conversion to open surgery, with two patients in each group of the study (6.9% in both groups).

There were no differences when surgical morbidity was evaluated only in patients from group A who had achieved a weight loss of 10% or superior with the balloon (32.8%) vs group H.

Discussion

We present a case-control study with control cases paired by age, gender, and type of surgery, to avoid the bias of including two different types of bariatric surgery with different morbidity.

It is not clear in the published literature that the weight loss prior to bariatric surgery has any impact on surgical morbidity (10,13,16,18). In fact, the influence of pre-surgical weight on surgical morbidity is also uncertain. Retrospective recent studies, conducted in the maturity stage of laparoscopic surgery did not find that the evolution and morbidity related with IGB was different in super-obese patients (BMI > 60) compared to morbidly-obese patients with a BMI > 60 (34-36).

The value of the intragastric balloon compared with conventional treatments in order to achieve adequate weight loss has been under discussion (28).

In our series, the proportion of failed balloons which did not achieve a significant weight loss (TBWL > 10%) was 34.5%, which is a high rate and very similar to that reported in other studies (32), highlighting the importance of patient involvement and a close clinical follow-up of patients in multidisciplinary visits (25,26) in order to achieve the best results regarding weight loss. This will probably involve changes in clinical practice, establishing weekly or biweekly personalized visits, at least during the initial months after the IGB placement. Our patients were controlled by a nutritionist on a monthly basis and with group talks, similarly to the follow-up received by the control group.

This type of follow-up has not been the most adequate procedure to succeed with the preoperative IGB in order to achieve the appropriate weight loss, and could be the reason for the high rate of IGB treatment failures.

The mean weight loss (TBWL) reached in group A was of 16.28 (SD 9.75) kg, with a 23.5% EWL (SD11.6) and 34.6% EBMIL (SD 24.1). These values are similar to those described in the literature (4,22,24,37), with a 36.9% EWL in patients with effective balloons, and 15% in patients with balloon failure (32).

Balloon tolerability was very good in our series; we did not have to remove any balloon before the determined time and this is better than that published in the literature, which describes 4.2-11% of patients who required balloon removal due to lack of tolerability or complications (24,27-29,32).

Achieving weight loss by using the IGB entails some risks. Even though there is a low rate of complications with IGBs, there have been reports of deaths due to gastric perforation (24,38,39) or during the balloon removal procedure, additional to the risks inherent to general anesthesia in this type of patients (7).

A very high proportion of those patients undergoing IGB placement have vomiting and epigastric pain of variable intensity during the first days or weeks (37); in some cases, this has made them attend the Emergency Unit for management with intravenous drugs. Vomiting and epigastric pain are caused by the digestive system rejection of the balloon, which acts as a foreign body introduced into the gastric cavity. In fact, these cannot be considered as complications, but side effects of the intragastric balloon, and can be managed with analgesics, antiemetics and PPIs.

In our series, we had a total of 17.2% of complications associated with IGB, similar to the rate published (24,37). Only two patients out of 29 (69%) had complications that might be considered to be severe. The vast majority were mild cases, mostly endoscopic esophagitis, without any gastroduodenal ulcers. Only two patients experienced severe complications, but only one of them required hospitalization.

The essential question to be answered, and the objective of this study, is to try to determine if the preoperative IGBs is useful to reduce surgical morbidity in bariatric surgery. Only very few studies have been published regarding this topic (22,30,40,41), but these are heterogeneous, and some of them have been conducted in populations with extreme obesity (super-obese) who are not representative of the overall group of patients with morbid obesity.

Busetto et al. (22) compared, in a case-control study with 43 super-obese patients, the pre-surgical IGB balloon prior to laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB), and found a reduction in the rate of conversions to open surgery, in the time of hospital stay, and in complications during the procedure.

Zerrweck (21) published a case-control study with 23 super-obese patients who used IGB before surgery, followed by LGBP, compared with 37 control cases of their own historic group, with a mean BMI of 58.4 kg/m2, treated with LGBP. The balloon group achieved a weight loss of 5.5 ± 1.3 kg/m2 (EBMIL 11.2 ± 3.2%), p < 0.001, vs the control group. The time of the surgical procedure was lower in the balloon group, and the same for the rate of surgical complications, 8.6% in the IGB vs 35.1% in the historic group, p = 0.031.

Therefore, in light of these publications, it seems that IGBs could be useful in extreme obesity by reducing surgical morbidity.

However, other studies similar to ours concerning morbid obesity (excluding super-obese patients) have not found any differences in terms of post-surgical morbidity, conversion to open surgery, or mortality, even when taking into consideration other randomized studies which have compared patients with a significant weight loss on a strict hipocaloric diet vs patients without weight loss (18,42). In addition, low-calorie intake diets, even in super obese patients, have been shown to be as equally effective as IGB (43).

From the clinical point of view, relevant morbidity is the type of morbidity that can be classified as moderate or severe, and its value in this study reached 20.3% in group A and 27.3% in group H, which was not statistically significant. This morbidity rate can be ranked within the high range, according to data published in scientific literature (5-23.1%) (3,6-10,44).

There was a 27.6% surgical morbidity in group A with-out any significant differences regarding the 41.4% rate achieved in group H (Table III). When we analyzed the overall morbidity, considering post-surgical morbidity as well as that derived from the balloon in group A, there was no difference between groups, with 41% for both groups (Table III).

The post-surgical severe morbidity was 6.89% and 17.2% in group A and group H respectively, and was not statistically significant (p = 0.454). If we had found significant differences in terms of postsurgical morbidity, it could be argued that there was a bias because the H group had a significantly greater rate of ASA III patients compared to the IGB, which is much more when taking into account that the H group included the first patients treated during the bariatric surgical learning curve. For this reason, if there had been a protective effect by the balloon, it should have appeared clearly in our study.

As stated in other similar studies (35), it is often difficult to achieve enough statistical power in these type of studies. Therefore, in order to achieve statistical significance in the postsurgical morbidity of group H, the sample size of the study should have been increased to 364 patients (182 patients in each arm), which can only be attainable in multicenter studies. The NNT of the study would be 7, so we would need to treat seven patients with IGB to decrease any event of postsurgical morbidity, while also taking into consideration the cost of the treatment.

When comparing post-surgical morbidity exclusively in the subgroup with "effective balloons" vs their respective controls in group H, we did not find any statistical differences either. Likewise, other authors have not found any differences in the post-surgical morbidity of patients with effective IGBs vs the sub-group of non-effective balloons; moreover, they did not find that the balloon was useful to predict the efficacy of a subsequent restrictive bariatric surgery, such as gastric banding (32).

Another goal of our study was to evaluate the length of hospital stay and the time spent in the operating room. Similar to results previously published by other authors, we did not find any significant differences in the length of hospital stay, or the time spent in the operating room (6,17). Devices for stapling and linear cut are used for conducting the vertical sleeve gastrectomy. The presence of the intragastric balloon for a prolonged period of time will cause hypertrophy of the gastric muscular wall. This hypertrophy is even greater at the gastric antrum.

We found that patients with IGB presented hypertrophy of the gastric wall. This was clearly perceived by surgeons, and in some cases led to a technical complication for conducting the mechanical suture in LSGs, requiring the use of larger-sized staples, and causing concern regarding suture stability.

Our study offers the innovation of being conducted in a non-tertiary general hospital, reproducing the real clinical practice in the majority of hospitals in our country.

Despite the fact that bariatric surgery is the best treatment option for morbid obesity, hardly 15.4% of medical care physicians sent patients to specialized surgeons (45).

In those hospitals with limited access to bariatric surgery and with major waiting lists for surgery, IGBs can be considered as a tempting option, allowing weight loss, and achieving an optimal pre-surgery weight during the waiting period, and with a theoretical reduction in post-surgical complications which has not been demonstrated in our study.

Taking into account our results, a reduction in hospital stay of just one day or only half an hour of Operating Room time; failure in achieving a significant reduction in morbidity, associated to a 30% failure rate for balloons, and the morbidity inherent to IGBs (17.2%) make it impossible for us to consider the IGB as an effective approach.

Priced at 2,500 Euros, the cost of the balloon treatment is far from negligible. This price includes the cost of the balloon and the two endoscopic interventions for its placement and removal (the latter in an Operating Room). These facts are well verified in literature by some authors who labeled the balloon treatment as inefficient (25,29,45,46).

Regarding the limitations of our study, we must point out that the study groups were not completely homogeneous, with a higher ASA in the H group (historic group); however, despite this, we were not able to demonstrate a reduction in postsurgical morbidity in the cases (group A), which diminishes the importance of homogeneity between groups. Another limitation was the major rate of ineffective balloons, which reduced the study "n"; however, this fact shows the reality of intragastric balloons in daily practice.

In summary, although the use of IGB produced greater weight loss in relation to diet, it did not reduce post-surgical morbidity, time spent in the operating room, or the length of hospital stay. Additionally, it had a major rate of balloon failures if multidisciplinary actions and strict follow-up of the patients were not undertaken, a non-negligible rate of severe complications associated exclusively with the balloon, and an extra cost of over 2,500 Euros in terms of balloon costs.

The use of the balloon is not an effective measure to reduce post-surgical morbidity due to bariatric surgery. Therefore, in the absence of more conclusive studies, it should not replace other measures which are cheaper and present less complications, such as low-calorie diets (43).

Acknowledgments

We would like to give special thanks to Isabel Pua (Nutrition nurse) for her collaboration in this work with the nutritional follow-up of this cohort of patients, and to the Endoscopy Unit nurses: Concepción Cuevas, Anabel Isabel García, Susana Álvarez y Beatriz Rodríguez for their help and support on all the endoscopy procedures.

References

1. Gutiérrez-Fisac JL, Guallar-Castillón P, León-Muñoz LM, et al. Prevalence of general and abdominal obesity in the adult population of Spain, 2008-2010: The ENRICA study. Obes Rev 2012;3:388-92. DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00964.x. [ Links ]

2. Mazure RA, Breton I, Cancer E, et al. Intragastric balloon in obesity treatment. Nutr Hosp 2009;24:138-43. [ Links ]

3. Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, et al. Bariatric surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2004;92:1724-37. DOI: 10.1001/jama.292.14.1724. [ Links ]

4. Milone L, Strong V, Gagner M. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy is superior to endoscopic intragastric balloon as a first stage procedure for super-obese patients (BMI > or = 50). Obes Surg 2005;15:612-7. DOI: 10.1381/0960892053923833. [ Links ]

5. Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med 2007;357:741-52. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa066254. [ Links ]

6. Livhits M, Mercado C, Yermilov I, et al. Does weight loss immediately before bariatric surgery improve outcomes: A systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2009;5:713-21. DOI: 10.1016/j.soard.2009.08.014. [ Links ]

7. Spyropoulos C, Katsakoulis E, Mead N, et al. Intragastric balloon for high-risk super-obese patients: A prospective analysis of efficacy. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2007;3:78-83. DOI: 10.1016/j.soard.2006.11.001. [ Links ]

8. Livingston EH. Procedure incidence and in-hospital complication rates of bariatric surgery in the United States. Am J Surg 2004;188:105-10. DOI: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.03.001. [ Links ]

9. Giordano S, Victorzon M. The impact of preoperative weight loss before laparoscopic gastric bypass. Obes Surg 2014;24:669-74. DOI: 10.1007/s11695-013-1165-y. [ Links ]

10. Benotti PN, Still CD, Wood GC, et al. Preoperative weight loss before bariatric surgery. Arch Surg 2009;144:1150-5. DOI: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.209. [ Links ]

11. Fernández Mere LA, Álvarez Blanco M. Obesity and bariatric surgery: Anesthesia implications. Nutr Hosp 2004;19:34-44. [ Links ]

12. Lewis MC, Phillips ML, Slavotinek JP, et al. Change in liver size and fat content after treatment with Optifast very low calorie diet. Obes Surg 2006;16:697-701. DOI: 10.1381/096089206777346682. [ Links ]

13. Fris RJ. Preoperative low energy diet diminishes liver size. Obes Surg 2004;14:1165-70. DOI: 10.1381/0960892042386977. [ Links ]

14. Mechanick JI, Youdim A, Jones DB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the perioperative nutritional, metabolic, and nonsurgical support of the bariatric surgery patient - 2013 update: Cosponsored by American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the Obesity Society, and American Society for Metabolic & Bariatric Surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2013;9:159-91 DOI: 10.1002/oby.20461. [ Links ]

15. Williamson DF, Pamuk E, Thun M, et al. Prospective study of intentional weight loss and mortality in never-smoking overweight US white women aged 40-64 years. Am J Epidemiol 1995;141:1128-41. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117386. [ Links ]

16. Gerber P, Anderin C, Thorell A. Weight loss prior to bariatric surgery: an updated review of the literature. Scand J Surg 2015;104:33-9. DOI: 10.1177/1457496914553149. [ Links ]

17. Alvarado R, Alami RS, Hsu G, et al. The impact of preoperative weight loss in patients undergoing laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg 2005;15:1282-6. DOI: 10.1381/096089205774512429. [ Links ]

18. Alami RS, Morton JM, Schuster R, et al. Is there a benefit to preoperative weight loss in gastric bypass patients? A prospective randomized trial. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2007;3:141-5;discussion 145-146. DOI: 10.1016/j.soard.2006.11.006. [ Links ]

19. Huerta S, Dredar S, Hayden E, et al. Preoperative weight loss decreases the operative time of gastric bypass at a Veterans Administration hospital. Obes Surg 2008;18:508-12. DOI: 10.1007/s11695-007-9334-5. [ Links ]

20. Riess KP, Baker MT, Lambert PJ, et al. Effect of preoperative weight loss on laparoscopic gastric bypass outcomes. Surg Obes Relat Dis 2008;4:704-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.soard.2008.05.007. [ Links ]

21. Zerrweck C, Maunoury V, Caiazzo R, et al. Preoperative weight loss with intragastric balloon decreases the risk of significant adverse outcomes of laparoscopic gastric bypass in super-super obese patients. Obes Surg 2012;22:777-82. DOI: 10.1007/s11695-011-0571-2. [ Links ]

22. Busetto L, Segato G, De Luca M, et al. Preoperative weight loss by intragastric balloon in super-obese patients treated with laparoscopic gastric banding: A case-control study. Obes Surg 2004;14:671-6. DOI: 10.1381/096089204323093471. [ Links ]

23. Force ABET, Sullivan S, Kumar N, et al. ASGE position statement on endoscopic bariatric therapies in clinical practice. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;82:767-72. DOI: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.06.038. [ Links ]

24. Imaz I, Martínez-Cervell C, García-Álvarez EE, et al. Safety and effectiveness of the intragastric balloon for obesity. A meta-analysis. Obes Surg 2008;18:841-6. DOI: 10.1007/s11695-007-9331-8. [ Links ]

25. Fernandes M, Atallah AN, Soares BG, et al. Intragastric balloon for obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(1):CD004931. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004931.pub2:CD004931. [ Links ]

26. Force ABET, Committee AT, Abu Dayyeh BK, et al. ASGE Bariatric Endoscopy Task Force systematic review and meta-analysis assessing the ASGE PIVI thresholds for adopting endoscopic bariatric therapies. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;82:425-38e425. DOI: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.03.1964. [ Links ]

27. Doldi SB, Micheletto G, Perrini MN, et al. Treatment of morbid obesity with intragastric balloon in association with diet. Obes Surg 2002;12:583-7. DOI: 10.1381/096089202762252398. [ Links ]

28. Mathus-Vliegen EM, Tytgat GN, Veldhuyzen-Offermans EA. Intragastric balloon in the treatment of super-morbid obesity. Double-blind, sham-controlled, crossover evaluation of 500-milliliter balloon. Gastroenterol 1990;99:362-9. DOI: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)91017-Z. [ Links ]

29. Adrianzen Vargas M, Cassinello Fernández N, Ortega Serrano J. Preoperative weight loss in patients with indication of bariatric surgery: which is the best method? Nutr Hosp 2011;26:1227-30. [ Links ]

30. Genco A, Cipriano M, Materia A, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy versus intragastric balloon: A case-control study. Surg Endosc 2009;23:1849-53. DOI: 10.1007/s00464-008-0285-2. [ Links ]

31. Alastrue Vidal A, Sitges Serra A, Jaurrieta Mas E, et al. Anthropometric parameters for a Spanish population (author's transl). Med Clin (Barc) 1982;78:407-15. [ Links ]

32. De Goederen-van der Meij S, Pierik RG, Oudkerk Pool M, et al. Six months of balloon treatment does not predict the success of gastric banding. Obes Surg 2007;17:88-94. DOI: 10.1007/s11695-007-9011-8. [ Links ]

33. Strasberg SM, Linehan DC, Hawkins WG. The accordion severity grading system of surgical complications. Ann Surg 2009;250:177-86. DOI: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181afde41. [ Links ]

34. Tichansky DS, DeMaria EJ, Fernández AZ, et al. Postoperative complications are not increased in super-super obese patients who undergo laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Endosc 2005;19:939-41. DOI: 10.1007/s00464-004-8929-3. [ Links ]

35. Kushnir L, Dunnican WJ, Benedetto B, et al. Is BMI greater than 60 kg/m2 a predictor of higher morbidity after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass? Surg Endosc 2010;24:94-7. DOI: 10.1007/s00464-009-0552-x. [ Links ]

36. Abeles D, Kim JJ, Tarnoff ME, et al. Primary laparoscopic gastric bypass can be performed safely in patients with BMI > or = 60. J Am Coll Surg 2009;208:236-40. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.10.020. [ Links ]

37. Zheng Y, Wang M, He S, et al. Short-term effects of intragastric balloon in association with conservative therapy on weight loss: A meta-analysis. J Transl Med 2015;13:246. DOI: 10.1186/s12967-015-0607-9. [ Links ]

38. Escudero Sanchís A, Catalán Serra I, Gonzalvo Sorribes J, et al. Effectiveness, safety, and tolerability of intragastric balloon in association with low-calorie diet for the treatment of obese patients. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2008;100:349-54. [ Links ]

39. Dumonceau JM. Evidence-based review of the Bioenterics intragastric balloon for weight loss. Obes Surg 2008;18:1611-7. DOI: 10.1007/s11695-008-9593-9. [ Links ]

40. Melissas J, Mouzas J, Filis D, et al. The intragastric balloon - Smoothing the path to bariatric surgery. Obes Surg 2006;16:897-902. DOI: 10.1381/096089206777822188. [ Links ]

41. Zerrweck C, Sepúlveda EM, Maydon HG, et al. Laparoscopic gastric bypass vs. sleeve gastrectomy in the super obese patient: Early outcomes of an observational study. Obes Surg 2014;24:712-7. [ Links ]

42. Solomon H, Liu GY, Alami R, et al. Benefits to patients choosing preoperative weight loss in gastric bypass surgery: new results of a randomized trial. J Am Coll Surg 2009;208:241-5. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.09.028. [ Links ]

43. Leeman MF, Ward C, Duxbury M, et al. The intra-gastric balloon for pre-operative weight loss in bariatric surgery: is it worthwhile? Obes Surg 2013;23:1262-5. DOI: 10.1007/s11695-013-0896-0. [ Links ]

44. Sugerman HJ, DeMaria EJ, Kellum JM, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery in older patients. Ann Surg 2004;240:243-7. DOI: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133361.68436.da. [ Links ]

45. Dabrowiecki S, Szczesny W, Poplawski C, et al. Intragastric Balloon (BIB system) in the treatment of obesity and preparation of patients for surgery - own experience and literature review. Pol Przegl Chir 2011;83:181-7. DOI: 10.2478/v10035-011-0028-2. [ Links ]

46. Saruc M, Boler D, Karaarslan M, et al. Intragastric balloon treatment of obesity must be combined with bariatric surgery: a pilot study in Turkey. Turk J Gastroenterol 2010;21:333-7. DOI: 10.4318/tjg.2010.0117. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Luis Ramón Rábago.

Department of Gastroenterology.

Hospital Severo Ochoa.

Av. de Orellana, s/n.

28911 Leganés, Madrid. Spain

e-mail: lrabagot@gmail.com

Received: 22-09-2016

Accepted: 03-12-2016

texto en

texto en