Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Psychosocial Intervention

versión On-line ISSN 2173-4712versión impresa ISSN 1132-0559

Psychosocial Intervention vol.22 no.3 Madrid dic. 2013

https://dx.doi.org/10.5093/in2013a28

Current trends, figures and challenges in out of home child care: An international comparative analysis

Tendencias actuales, datos y retos en las medidas de protección a la infancia com separación familiar: Un análisis comparativo internacional

Jorge F. del Valle y Amaia Bravo

Child and Family Research Group, Department of Psychology, University of Oviedo, Spain

ABSTRACT

This article closes the special issue of this journal about an international review of out-of-home child care, principally family foster care and residential care, tough several aspects related to adoption were included as well. Although a comparison on some data about residential and foster care, or kinship and non-kinship care, is carried out, the article tries above all to make a reflection on the implications of several themes that have emerged as more interesting or important. Matters such as the use of residential care and its role in the current child care system, the overrepresentation of ethnic minorities in foster care in several countries, the situation of unaccompanied young people asylum seeking, the use of adoption as a permanent solution, the challenges of the transition to the adulthood from care, the relevance of the professionalization and models based on social pedagogy, the evaluation and planning based on data, and the current financial crisis and its impact on child care systems are some of the remarkable topics that will be reviewed.

Keywords: Family foster care. Residential care. Out-of-home care. Adoption. Child care system

RESUMEN

Este artículo cierra el número especial de esta revista sobre una revisión internacional de las medidas de protección infantil con separación familiar, fundamentalmente acogimiento familiar y residencial, pero que ha incluido también diversos aspectos referidos a la adopción. Aunque se realiza una comparativa de algunos datos sobre acogimiento familiar y residencial, o los tipos de acogimiento en familia ajena y extensa, el artículo trata sobre todo de realizar una reflexión sobre las implicaciones de diversos temas que han emergido como más interesantes o importantes. Cuestiones como el uso del acogimiento residencial y su papel en el actual sistema de acogimiento infantil, la sobrerrepresentación de minorías étnicas en las medidas de acogimiento en diversos países, la situación de los menores extranjeros no acompañados, el uso de la adopción como solución definitiva, los retos de la transición a la vida adulta de los jóvenes en protección, la importancia de la profesionalización y los modelos basados en la pedagogía social, la planificación y evaluación basada en datos y la actual crisis financiera y su impacto en los sistemas de acogimiento infantil son algunos de los temas destacados que se repasarán.

Palabras clave: Acogimiento familiar. Acogimiento residencial. Medidas de separación familiar. Adopción. Sistema de acogimiento infantil

This article closes this ambitious special edition, in which we have looked at the state of child protection, and in particular out-of-home child care, in 16 countries which represent very different cultural contexts, historical backgrounds, and social welfare systems. The review included the USA and Canada, considered as countries with liberal welfare systems, as are Australia and New Zealand, although the latter have some significant cultural features. The English and Irish systems have traditionally been considered liberal, although arguably their categorisation depends on the point in time one refers to and it is obvious that there are enormous differences between them. Two countries were included which are clear representatives of the social democratic model of the Nordic countries, Sweden and Norway, and, staying within continental Europe, we looked at the protection systems in Germany, The Netherlands, Switzerland, and France, where a liberal-conservative welfare system is predominant, albeit with many differences in the details. Italy and Spain were added as representatives of a different model, sometimes called the Mediterranean model, which is characterised by the importance of the family as a welfare provider. Finally, Hungary and Romania were included as examples of Eastern European countries in the transition from communist state protection towards the current trends of the welfare state.

This article does not attempt to be a comparative analysis which would allow us to extract universally valid generalisations, because if this international review makes one thing clear, it is the enormous influence on the child protection systems of the historical and cultural conditions in which they developed. Despite the obvious globalising tendencies from which this field cannot escape, the cultural factors in each country continue to have a crucial influence on the ways in which child protection is organised. While it is true, as Gilbert (2012) said, that one can see a trend converging towards a model based on the promotion of child development which addresses child protection at the same time as attending to family welfare, the specific way in which this is done in social intervention programs is still noticeably different.

The intention of this article is to highlight a series of principal themes arising from the analysis of the 16 countries allowing us to address some of the grand common themes, as well as some specifics, with the aim of encouraging reflection on the way in which our societies try to guarantee the welfare of children and their families. If our objective of bringing together so much information from so many countries has been ambitious, this article has humble goals, and the wealth of this special issue will be, above all, in what the reader takes away from it.

From a "rescue" model to a model promoting development and well-being

Although awareness of the importance of the family as a context for development appeared in some countries before others, the truth is that until the twentieth century child protection was generally based on institutionalisation. The large care institutions were understood to be places where people were "rescued", not only in the most literal and physical sense as with those abandoned children rescued from an infallible death, but also in a spiritual or religious sense in which their souls were also saved. Hence, the enormous role played by religious institutions in this area (Courtney, Dolev, & Gilligan, 2009). This method of protection was aimed exclusively at children, leaving the family of origin outside the protection framework, as they were generally considered to be responsible for the child's lack of care.

In the case of Eastern European countries, such as Hungary and Romania, a different form of child "rescue" can be seen, in this case led by a totalitarian state. Institutionalisation was used to exert ideological control over the citizens and as a way to prevent families from having an unorthodox, free or alternative influence on their children's education (what might have been considered a petit-bourgeois practice). Finally the review of the Australian child protection system allowed us to see another form of child "rescue", in which Indigenous children were separated from their original culture and subjected to a process of socialisation in the dominant culture through institutionalisation.

During the twentieth century, with the appearance of legislation protecting minors, protection measures spread, which allowed the "rescue" of children as a way of separating them from unsuitable family situations, even against the will of the parents. Although the trend towards placing children with foster families rather than in institutions had begun, the dichotomy of the child as a victim and the family as responsible remained in this model, which we might call the protection of minors model. The child protection systems in the USA or the UK are clear examples of a model which is strongly focused on detection of child abuse and coercive measures to separate the child from his or her family. This is probably a consequence of the impact of investigations into child abuse in the 1960s. These models, which are based on the idea of permanency planning, have promoted the use of adoption measures as a stable, definitive solution in cases with a negative prognosis of family reunification, which avoids long stays in provisional foster care situations.

On the other hand, in Nordic countries, the tradition of focusing on social problems as something which is strongly associated with access to education and equality of opportunity leads to a model which is based on offering support to families as an indirect, but necessary, way to address children's welfare. As can be seen in the review, the rights of the parents over their children are respected even to the point of making adoption without their consent impossible (even in cases of severe mistreatment), as happens in Sweden, or hardly using this measure even though it is possible, as in Norway. The ideal of family reunification and rehabilitation of adults means that the child care services work in a short-term theoretical dimension, despite the fact that, in reality, this means prolonged stays in out-of-home care. Other cases, such as the Netherlands, have also made a strong commitment to the family support model, intervening on the fundamental basis of voluntary agreement and without using adoption as a stable solution.

As Gilbert (2012) noted, recent years have seen the appearance of the trend converging on a model which combines elements of dealing with the families while at the same time guaranteeing the protection of the children. This is probably because, depending on the case, one type may take priority over the other but without both possibilities the system may become very inflexible. It is interesting to observe that in some countries, which have only recently incorporated the idea of the state intervening as a welfare provider and which had relied on the natural protection of the family, such as Spain or Italy, legislation includes a focus on both modes in a very balanced way. In the case of Spain, following the legal framework of 1987 which modernised child welfare, it became possible for the authorities, without the court's intervention, to assume guardianship over a child in the case of flagrant child abuse (the family has the option of appealing to the courts). In 1996 the law introduced mandatory reporting for all professionals (health, education, etc.) and for citizens in general; any occurrence of neglect or abuse must be reported, which would be an example of a strong child protection component. At the same time, the law established the priority of attention to the family, putting into place an extensive network of family support services with models integrating social work, psychotherapeutic services, and education or social pedagogy at municipal level.

The convergence towards a model which values child development and which requires child protection and aid to families has been helped enormously by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Its influence, as seen in the reviews in this special issue, has been crucial not only in driving modernisation in countries such as Hungary, Romania, Italy, or Spain with a recent past of significant institutionalisation, but also in countries like Switzerland, where it prompted significant questioning of their child protection practices despite being a rich country with a high level of welfare.

The changing profile of children under protection: When we found out the answer, the question changed

The natural evolution, the transition from institutional care to family placement, which was becoming apparent at varying rates in each country, enjoyed a unanimous consensus. However, the cultural and economic conditions have not always allowed this transformation. In Italy and Spain, the cultural value placed on caring for one's own children clashed head-on with the idea of strange families providing foster care. In the case of Romania, the efforts and progress made so far towards family placement is in grave risk due to the economic crisis (1,000 foster carers resigned in 2012 due to the lack of economic support). Nonetheless, legislation, international directives, and research provide a significant consensus about the need for children in out-of-home care to enjoy a family environment rather than an institutional one. Even in cases where residential care programs are continuing to be used, they will have to be designed as small, normalising, family homes.

This clarity of ideas has become clouded due to the changing profiles of the population under care. In recent decades there has been significant increase in adolescents needing protection measures, who at the same time demonstrate serious behavioural problems, mental health disorders, or serious disability issues. In the same vein, a very particular group of adolescents, unaccompanied asylum seekers, have provoked the increase in residential care places in many very different countries, such as Spain or Sweden. The data presented in this review by various countries shows that the residential care population is fundamentally (almost always around 80%) adolescent. To the typical difficulties of the adolescent development stage, one must add severe emotional and behavioural problems and cultural integration challenges making this group particularly difficult to deal with appropriately.

Therefore, as we had already designed a system based on the provision of family care and family preservation, these especially complex profiles demand specialised programs with a more therapeutic function, ushering in a type of intervention which has been absent up to now. Within this framework, one must understand the enormous concern in many countries about the use of therapeutic residential care and the search for effective models (see an international review in Whittaker, Del Valle, & Holmes, in press). Evaluations must be considered in terms of effectiveness, because these adolescents need short term treatments which prevent their social exclusion (something which is very likely in those leaving care, as research has demonstrated).

Child protection now faces a challenge which will not be solved by approaches based on using family placement to substitute for an inadequate family environment. These new profiles have other, varied, and complex needs, which require new, much more specialised, and costly interventions. The current financial crisis makes the situation even worse.

It is important to highlight that in foster care too, solutions such as the Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care model have been used for these types of cases as an evidence-based program (Leve et al., 2012). In any case, just as we thought that we were approaching a clear consensus about the needs to be met for at-risk children and the types of programs to be pursued, new needs have arisen as well as new profiles which call into question some of our principles and approaches.

The double vulnerability of children from ethnic minorities

Child protection is fundamentally about addressing the needs of minors in vulnerable situations due to a lack of appropriate care from their families. The international review in this special issue demonstrates that there is another vulnerability, in this case cultural vulnerability, which affects many different ethnic minorities. The overrepresentation of Indigenous minorities in Australia, New Zealand, and Canada, of Roma children in Romania and Hungary (and also in Spain although in a much smaller proportion), of Afro-American families in the USA, and of diverse immigrant families in Germany and other Central European countries necessitates a more general consideration of the relationship between child welfare, the conditions of the general access to services, and equal opportunity for the various minorities. It seems clear that one cannot separate general levels of well-being and these minorities' social inclusion in society from what happens in child care to the children from those families.

More participative strategies are required, possibly with community intervention models in which minority groups take the lead and might propose alternatives for their specific situations, which respect their cultural characteristics and the need that children not be placed with families whose cultures might clash with their values and experiences. Some evidence of cooperation in this direction can be seen between the government and Maori groups in New Zealand, and the development of community psychology in Latin America may contribute some interesting experiences with minorities.

Geographical movement in a global world: Unaccompanied asylum seekers

A much repeated theme throughout this 16-country review is the need to deal with young people who are unaccompanied asylum seekers. The possibility of moving between countries and particularly the breakdown of separation between more developed countries and the so-called third world has led to a migration, the volume and repercussions of which have yet to be properly assessed.

In the case of Spain, there has been a significant increase in the number of new referrals to residential care per year, from 5,800 in 2000 up to 10,800 in 2008. Although there are no specific figures, the main reason for this rise is thought to be the admission of unaccompanied minors. This has led to the need to open large numbers of residential resources specifically for this group, as their sudden arrival makes placing them in existing facilities difficult. Moreover, in countries like Spain it is understood that dealing with them as minors means treating and protecting them like any other (native) minor, in contrast to other countries where there is an asylum request which may be granted or not. In Spain, the big wave of arrivals has been minors from North Africa, whereas in the Nordic countries (and especially in the case of Sweden) they are dealing with minors from war-torn areas such as Iraq, Somalia, or Afghanistan.

These groups also present specific needs to the protection system because, owing to their age, which is almost always close to 18, they need immediate preparation for the transition to adult life and entry into the labour market. This transition, which is difficult enough for natives, is even more complicated for someone who does not know the language or the customs of the place in which they find themselves. Added to that is the current economic crisis, which in some countries like Spain means that there is little possibility of entering the labour market for young people in general and especially for this group.

Dealing with unaccompanied foreign young people poses a serious challenge to child care services because, in addition to the resources needed following the numerous arrivals in some countries, it requires the use of residential solutions which, as mentioned before in regard to profiles, are tending to disappear. Furthermore, the directives on working with families or reunification, which are the foundations of the new systems, end up being inapplicable. This is a hugely specific work, the demands of which, just to complicate matters, depend on unpredictable migratory flows related to border policies, international relations, and complex political negotiations.

Family foster care vs. residential care

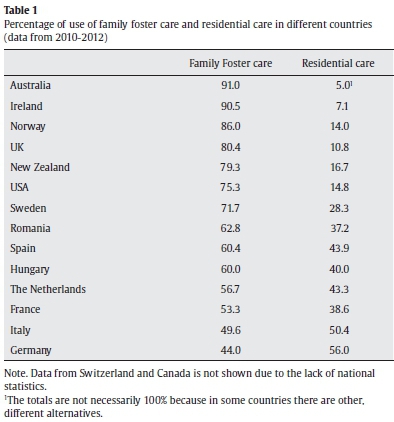

There is a unanimous consensus throughout the countries in the review on the need for children to enjoy a family environment in order for their development needs to be met. When it is not possible for a child to stay with their birth family (despite family support, which must be tried), a substitute family must be sought to fulfil this role. Practically all of the countries have the same history of using care institutions, although the impetus to change this has emerged at very different times in each one. The general tendency, in any case, is a reduction in the use of residential care in favour of family foster care in all countries. This tendency is apparent in the statistics, even in the last decade, in almost all of the countries reviewed. Table 1 shows the proportions of use of residential care and family foster care. It is clear that in English-speaking countries residential care has been reduced the most, especially in Australia and Ireland but also in the UK, New Zealand, and the USA. The case of Ireland merits highlighting because there had been a tradition of large religious institutions in catholic countries until very recently and in a very short time there has been the implementation of an almost exclusive family foster care model in this country.

The Scandinavian countries, especially Norway, show a clear balance in favour of family measures, although it is notable that in Sweden the percentage of residential care is double that in Norway. It must be borne in mind that Sweden accepts many more (some thousands per year) unaccompanied asylum seekers for which it could be difficult to use any measure other than residential care.

Romania and Hungary have managed to reach a state of family measures being used in the majority in a short time, making a commendable transition from the almost exclusive use of institutionalising measures by the previous political regime. Nonetheless, the current economic crisis is having a profound effect, putting this progress at risk.

The case of Spain, which has only had foster care in its legislation since 1987, is special because the vast majority of family placements are with relatives, particularly grandparents. This inflates the figures for family foster care immensely, even if many of these cases are not situations of notified substantiated mistreatment but rather formalisations of informal arrangements in which at-risk situations had not occurred.

Finally The Netherlands, France, Italy, and Germany have the lowest proportions of family foster care. It is important to bear in mind that in some countries such as The Netherlands, residential care includes programs aimed at young offenders, as they are in the same system of youth care. When it comes to Germany, one must also remember that their system deals with much older young people (up to 21 or even 27 in special situations) which might mean residential care being used more frequently.

It is interesting to observe that the countries which have a tradition of social pedagogy, as in Central Europe and the Mediterranean area (particularly Spain and Italy, where social education has been firmly established as a discipline and as a profession), residential care has notably been maintained. It is in precisely these kinds of programs that the professional work of pedagogues and social educators has been aimed at, leading to a significant reform in practice in this area, with a high level of professional qualification, a theoretical model, and a series of instruments (individualised educative planning, etc.) which have enormously improved the quality of residential care. In contrast, in English-speaking countries, where this model of social pedagogy has not been developed, there has been significant criticism of the practice of residential care, and it continues to present big problems because of the low qualification of residential staff and the lack of clear intervention models. There are some attempts to translate the social pedagogy model to countries like the UK (Berridge, 2013), so far they are in their very early stages.

It is important to highlight the fact that residential care still deals with, in large part, adolescents with the following types of profile: young people with serious behavioural problems or mental health disorders; young people with serious rebellious behaviour against their parents, including aggression and violence towards them; young people who need support in their transition to adult life when they are close to the age of majority or having already passed it and remained in residential care for a further time; and unaccompanied asylum seekers, which is especially relevant to certain countries.

Therefore, one of the most important functions of residential care is to deal with adolescents with diverse problems which are scarcely compatible with family foster care. One important conclusion is that residential care seems to have an important "treatment" function and is not only an alternative measure to the family. Treatment can be understood therapeutically, as in those therapeutic residential care programs for young people with serious behavioural problems, but also it can mean the acquisition of skills for independence in programs of transition to adult life or intensive training in language and culture for recently arrived asylum seekers. These functions are a long way from those needed for children in care (particularly the youngest) who require a substitute family home.

Some documents which are extremely critical of residential care, such as the Stockholm Declaration in 2003 on Children and Residential Care, seem not to take into account the current different functions of residential care, some of which are very difficult to carry out in family foster care and may result in confused conclusions and an excessively simplified vision.

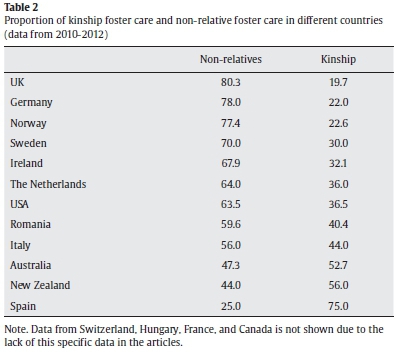

Kinship foster care vs. non-relatives foster care

One of the most interesting developments in foster care to study is that of kinship care. As will be appreciated in Table 2, there are enormous differences, with the UK as the country with the lowest use of the relatives in placements, followed by Northern and Central European countries and, at the opposite end of the spectrum, in a situation unlike any other country, we find Spain, where family foster care is primarily due to the efforts of the child's family (60% grandparents). It is obvious that in Spain it has not been possible to create a culture of family foster care with volunteer families caring for unknown children. It is also important to say that among the 17 autonomous communities there are significant differences in this area.

It is also notable that in Australia and New Zealand the balance is in favour of kinship care. Equally, Munro and Gilligan's review article in this publication focuses precisely on the change which is apparent when it comes to the increased trust in kinship care in both the UK and Ireland. As a matter of fact, in Scotland kinship care is already at 25%, whereas in England it is only 11%.

Recent research has shown that kinship care is a very special situation, dealing, as it does, with family environments that require significant economic, as well as technical support -something which is not always correctly forthcoming. In the face of the lack of confidence that these limitations can cause, one must applaud the strength of motivation of the fosterers, their long term commitment and some good results in terms of permanence and low probability of breakdown (Del Valle, López, Montserat, & Bravo, 2009). Nevertheless, one must also bear in mind that in many countries this measure is much cheaper than others and extending the use of kinship care without adequate support can be a dangerous way of saving costs in times of crisis. These families need, as has been identified, strong economic and professional support to allow them to get the best results.

The efforts of social policies in favour of kinship care, with the necessary assessments to check their suitability and support for training and supervision, in addition to economic support, may also have an enormous impact on making use of a country's own natural social resources, which would enhance a sense of community and solidarity.

The use of adoption as a definitive solution

One of the major differences between countries and systems is the use made of adoption as a possible definitive solution for those children who have a very negative prognosis for reunification. It forms part of the most representative practices of Gilbert's (2012) model of child protection, embracing the right of the child to have a stable family and paying less attention to the rights of the family to maintain links with the child. In the case of the USA, this idea has been reinforced in the philosophy of permanency planning since the 1980s and, as much there as in the UK, adoption is a fundamental instrument for a definitive solution in case of lack of protection.

On the contrary, countries such as the Netherlands and Sweden do not allow adoption against the wishes of the parents, and in Norway, Germany, and Ireland it is permitted but not promoted and is only infrequently used. Other countries such as France, Australia, and New Zealand demonstrate a moderate use of adoption with a goal of permanence. Alternatively, in other countries legislative changes are being made to provide agile systems so that children can be placed with an adoptive family as soon as practicable if reunification with the birth family is not possible, as in the case of Spain and Romania.

This is one of the most delicate themes in child protection, as it is an irreversible decision which needs a very rigorous evaluation of the family situation. On the one hand, the rights of the child to a stable and definitive family environment must be respected but, on the other hand, it goes against the criteria of giving priority to family reunification and against the creation of a system which tries at all costs to rehabilitate the birht parents in their parental role (as happens in those models centred on services to the family). In Spain, a legal provision in 2007 established that families whose children had been placed out-of-home for protection, and as such had forfeited their guardianship (patria potestad), have two years to show that they have recovered from the situation that led to the separation. To that end, the child protection services must assist these families in their treatments, whatever they may be (drug addiction, mental health, etc.), and particularly in parenting skills. After these two years, if there is no significant rehabilitation child services may take the decision to definitively suspend parental authority and allow the adoption of the child. This measure is taken to avoid long stays as shown in the research, especially in residential care (López & Del Valle, 2013) but also in family foster care (Del Valle et al., 2009).

Some countries, such as Romania, have a recent past in which children were frequently removed from institutions for adoption in other countries as a way of avoiding an institutionalised life. Following their accession to the European Union and the associated required reforms concerning child welfare, together with the significant positive changes presented in the corresponding article in this special issue by Anghel, Herczog, and Dima, a brake has been put on the exit of children to international adoption. They have tried to promote national adoption instead, but the figures are very low and Romanian families are reluctant to adopt children who have been in residential care.

It seems clear that, throughout this review of different countries, there is a tendency to find a balance between a focus on child protection and family service, which is particularly visible in the extension of family intervention programs aimed at preservation, which offset the traditional use of out-of-home care and the use of prevention programs. However, the question of using adoption as a definitive formula seems to clearly divide the countries between those more disposed to focus on the rights of the child to a family and those willing to give more chances of reunification to the birth families and maintaining links, although children stay in provisional situations for many years. In this sense, the Swedish attempt to use the transfer of guardianship (as adoption without consent is not permitted) to foster carers seems to be an intermediate solution, albeit one which is facing significant obstacles.

Transition to adult life

Traditionally, the protection system for minors, as the name suggests, is aimed towards providing care and services up to the time when a person reaches his or her majority, normally 18 years old. This means that young people leaving care are faced with situations in which they may feel helpless, and many of them return to their homes, inadequate though they may be, when faced with the lack of alternatives. In other cases they survive without the support of the services which had previously protected them, leading to a real risk of social exclusion. The research has shown that the process of transition to adult life for these young people is compressed and accelerated (Stein, 2006) compared to the rest of the population and the figures for unemployment and marginalisation are very high.

The transition to adult life has been shown to be one of the most relevant topics in research in many countries as can be seen in the international review by Stein and Munro (2008) or the special issue edited by Stein, Ward, and Courtney (2001). The research has found significant differences in respect to its inclusion in legislation obligating specific attention of this group (or similarly the recognition that this group represents a high priority social problem) and in the type of resources which are used for support. Accordingly, we must highlight Germany raising the age for protection services to 21 and even up to 27 in certain cases.

As was to be expected, in some countries such as Spain, with a strong family tradition, the processes of transition to adult life are supported by staying with the families, something which happens both in cases of kinship care (which is natural) and in foster care with non relatives, which is more surprising (Del Valle et al., 2009).

In the case of Norway, with its strong social welfare system, this issue appears to be lacking in the legal framework, maybe because it is understood that this group will, as they become adults, enjoy the ample coverage that all citizens have in this system. Nonetheless, the specific needs that they present do not seem to be well covered in this way, as the corresponding article in this special issue shows.

Professionalization, the social pedagogy model, and making up for lost time

One aspect in which we can see enormous differences, very clearly in the case of residential care but also in the makeup of the interdisciplinary teams of child protection services, is the tradition of the social pedagogy model and its corresponding professions (social pedagogues and orthopedagogues in Central Europe, social educators in Italy and Spain). Outside continental Europe, in the UK, the USA, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, child protection is a field of work which is fundamentally based on social work. Whilst this has had significant development as a profession which is valuable and serves many purposes in child care cases, it is a very limited model for furnishing qualified professionals to residential care programs. The lack of appropriately qualified staff is one of the biggest problems highlighted in these countries and has often been identified as related to deficient practices and a lack of results.

Accordingly, the more frequent use of residential care in some countries in Southern and Central Europe, which, furthermore, is fundamentally focused on dealing with adolescents with significant problems, should not be seen simply as a case of "delayed development" in respect to other countries in which it has been practically eradicated. It is better to think of these professional programs, with highly qualified staff, which have been designed following a psycho-social-educative intervention framework, as an alternative worth bearing in mind. In countries where the staff is not suitably qualified and there are no intervention models of this type based on social pedagogy, residential care demonstrates serious problems due to its high cost and lack of results, including continual placement changes, etc. It is important to assess residential care according to the specific conditions in each country and the model used to provide these services, and to require that the services are provided by personnel who are sufficiently highly qualified to meet the complex needs of these young people.

Eastern European countries, exemplified in this special issue by Hungary and Romania, have had to face the challenge of making up for a lot of lost time in this sense, something which has also happened in Spain. We refer to the fact that in these three countries, totalitarian regimes (in Spain, the military dictatorship between 1939 and 1978) eliminated many 'helping professions' such as social work, pedagogy and even psychology. In the case of Spain they only slowly reappeared from 1970 onwards and were consolidated in the 1980s, becoming a fundamental part of professional child care teams, to which were added the social educators as a new profession in the beginning of the 1990s. As was seen in the review of Hungary and Romania, there was a similar experience and the need to create new interdisciplinary teams and to develop corresponding programs and services has posed an organisational challenge that has not always been sufficiently well met.

In this respect, the Swiss situation is notable because it is only in recent years that they have created teams of professionals (some 200 in the entire country) and corresponding service networks to intervene in child protection cases.

Planning and needs evaluation without data?

It is well known that accumulating a lot of data is not synonymous with scientific understanding. In this special issue we have made an effort to present current data on the principal measures of child protection in various countries, and the enormous complexity they represent is evident. Depending on the country, the concepts may cover differing practicalities (the most obvious case being the quantity of programs encompassed by the term residential care) and the data may be collected with different criteria (as in the case of Spain with the inclusion of kinship care cases, which, in other countries are not counted because they are not child protection cases).

Nevertheless, the planning of social interventions is based on evaluations of social problems or, to be more exact, of social needs. Without data it is impossible to know what new problems are emerging or to be able to prepare an appropriate response. This situation is more serious in child protection because some changes in interventions need changes in legislation, which means long periods of drafting and approval.

It has been evident in this international review that there is an enormous variety of systems for collecting information on child care systems. One of the factors which has been shown to be crucial is the process of administrative decentralisation for managing childcare services. In particular, those countries with a federal structure have the challenge of being able to collect data from each state or canton in order to carry out a national evaluation (as some of them make national plans or implement laws at this level). Spain may be considered in this group because, although the autonomous communities do not function as a federation, there is a significant degree of independence with respect to the national government. In this review, Canada, and especially Switzerland, have described a situation in which it is not possible to provide data for the country as a whole, while other federal models, such as the USA and Germany, have very effective monitoring systems. It has also been possible to appreciate the peculiarity of the management model of a country as large as France, where the management of services lies with the departments and local authorities but which retains significant centralised power in the national government.

Efforts must be made to have rigorous data collection systems which allow early detection and needs assessment. One example of the failure of those systems can be seen in the case of Hungary and Romania, where the presence of Roma children in out-of-home care was hidden in the data because data on ethnicity was understood to violate confidentiality. The consequent effects have been much more harmful because the data does not allow the evaluation of this population's overrepresentation in child care or the analysis of socioeconomic causes so this group's access to equal opportunities has suffered and demands other more general and ambitious policies.

Spain shares these problems because, while there are some national statistics to which the autonomous communities must contribute data, there are no homogeneous criteria for data collection in each autonomous region, so combining them together in a national system is difficult. On the other hand, the system was always focused on administrative aspects and failed to collect variables on the profile of children and their families, which gets in the way of any needs evaluation. A relevant example is the lack of knowledge in our country about the true figures of unaccompanied asylum seekers, who are supposed to have arrived in great numbers in all of the communities (especially in the Canary Islands and Andalusia), and whose arrival has led to the massive increase in residential care places, but about whom we have no exact data.

The financial crisis and its effects on child care

The majority of the review articles make reference to the impact of the great economic crisis we have experienced in recent years. This has been dramatic in countries such as Ireland and Spain, subject as they were to the intervention of the European authorities. Other countries such as Italy have remained in a perilous state, while others like Hungary and Romania, which were in the middle of a transition of their entire economic structure, are threatened by the interruption of this process and stagnation in a very precarious situation.

Cuts to social services spending in these countries have been and continue to be severe and have affected all sectors including child care. Countries are trying to make huge changes in their protection systems, some of which are truly staggering, such as in the case of Ireland, which is transforming a system that was traditionally based on religious residential institutions to one which is focused on the family and family foster care that appears firmly consolidated. Equally noteworthy are the efforts of Spain and Italy in carrying out this kind of modernisation that originates, as in Ireland, from a family-type model that now seems irreversible despite significant cuts. The case of Hungary and Romania is more worrying because the changes there have been very recent and there is still a certain confusion and lack of stable criteria, as examined in the article on Hungary, or the lack of progress in family fostering due to financial issues in the case of Romania. These systems will probably have to struggle to maintain the changes they have made in the face of very adverse conditions, without having had time to consolidate the new model.

Nevertheless, the economic crisis is related to globalisation and throughout the reviews of so many countries that have been done in this special issue it is easy to see the effects on all of them. The most important effect, from my point of view, is the introduction of cost criteria as something which has become a priority in child care management. It is true that economic considerations are very relevant because, in general, child care systems deal with large budgets, and measures such as residential care are particularly costly, especially if they are specialised programs for adolescents with behavioural problems (the demand for which is growing in many countries). The same can be said for professional family foster care programs which have been described in various countries and which in France is generally the model of choice.

Some decisions about what is appropriate for child protection may be affected more and more by cost reduction, and care must be taken not to cloak the cheapest option as the one which is in the best interest of the child. Another very different point is the rigorous evaluation of program results, including efficiency or the relationship between cost and result. This implies the need for a good costing calculation system, for which there are interesting instruments (Ward, Holmes, & Soper, 2008) and the incorporation of the idea of return on investment used in some preventative programs and applying it to efficiency calculation in child care programs in general.

We live in a time of big political pressure to reduce spendind, and professionals, researchers, and program managers will need to agree upon criteria for effectiveness and efficiency based on the needs of the child and their family, so that we can confront possible arbitrary cuts. This type of international comparison may prove to be an important consideration.

Conflicts of interest

The authors of this article declare no conflicts of interest.

References

Berridge, D. (2013). Policy transfer, social pedagogy and children's residential care in England. Child and Family Social Work. Article first published online: 21 NOV 2013, DOI: 10.1111/cfs.12112 [ Links ]

Courtney, M., Dolev, T., & Gilligan, R. (2009). Looking Backward to See Forward Clearly: a Cross National Perspective on Residential Care. In M. Courtney & D. Iwaniec (Eds), Residential Care of Children (pp. 191-208). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [ Links ]

Del Valle, J. F., López, M., Montserrat, C., & Bravo, A. (2009). Twenty years of foster care in Spain: Profiles, patterns and outcomes. Children and Youth Services Review, 31, 847-853. [ Links ]

Gilbert, N. (2012). A comparative study of child welfare systems: Abstract orientations and concrete results. Children and Youth Services Review, 34, 532-536. [ Links ]

Leve, L., Harold, G. T., Chamberlain, P., Landsverk, J. A., Fisher, P. A., & Vostanis, P. (2012). Practitioner Review: Children in foster care - vulnerabilities and evidence-based interventions that promote resilience processes. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53, 1197-1211. [ Links ]

López , M., & Del Valle, J. F. (2013). The waiting children: pathways (and future) of children in long term residential care. British Journal of Social Work (Advance Access published October 7, 2013). doi:10.1093/bjsw/bct130 [ Links ]

Stein, M., Ward, H., & Courtney (2006). Research review: young people leaving care. Child and Family Social Work, 11, 273-279. [ Links ]

Stein, M., & Munro, E. (2008). Young People's Transitions from Care to Adulthood. International Research and Practice. London: Jessica Kingsley. [ Links ]

Stein, M., Ward, H., & Courtney, M. (2011). Young People's transitions from care to adulthood (Special Issue). Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 2409-2540. [ Links ]

Ward, H., Holmes, L., & Soper, J. (2008). Costs and Consequences of Placing Children in Care. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [ Links ]

Whittaker, J. K., Del Valle, J. F., & Holmes, L. (in press.) Therapeutic Residential Care for Children and Youth. Exploring Evidence-informed International Practice. London: Jessica Kingsley. [ Links ]

Correspondence:

Correspondence:

e-mail: jvalle@uniovi.es

Manuscript received: 15/05/2013

Accepted: 15/11/2013