In the large amount of literature on the relationship between parents and their adolescent children, there is a consensus that authority figures have to enhance their children's autonomy through empowering relationships (e.g., García & Gracia, 2009; Morton et al., 2010, 2011; Popper & Mayseless, 2003; Rodrigo, 2016). Specifically, Popper and Mayseless (2003) suggested the analogy of good parents as good leaders who display transformational behaviours. Thus, transformational leaders and good parents share common traits: both show sensitivity and responsibility through individual consideration; both transmit acceptance and non-judgement, providing opportunities through significant experiences; both establish rules and flexible limits; and both are positive examples with which to identify.

As previous research indicates (e.g., García & Gracia, 2009, 2014), in order to understand the functionality of parenting styles it is important to know the social context in which they take place. Specifically, families in the Spanish context have been categorized within a type of collectivist and horizontal culture, where egalitarian relationships are emphasized, with attention placed on providing acceptance, affection, and involvement in the socialization of the children, and where controlling behaviors are perceived as negative practices (e.g., García & Gracia, 2009; García, Serra, Zacarés, & García, 2018; Gracia, Fuentes, García, & Lila, 2012; Gracia, Lila, & Musitu, 2005). In this line, the transformational parenting style would meet the criteria of empowerment and support for autonomy (e.g., Popper & Mayseless, 2003) and could be considered an optimal parenting style in Spanish and similar cultures.

The literature suggests some beneficial effects of transformational parenting behaviours on adolescent children. Thus, fewer aggressive behaviours have been found in sports with adolescent athletes, claiming, based on Banduras' (1986) social learning theory, that parents are behavioural models for their adolescent children (Tucker, Turner, Barling, & McEvoy, 2010). In the same vein, transformational parenting has been positively associated with healthy behaviours, physical activity, and life satisfaction in their adolescent children (Morton et al., 2011; Morton, Wilson, Perlmutter, & Beauchamp, 2012). Morton et al. (2011) found empirical support, suggesting that parents who displayed transformational parenting behaviours promoted self-regulatory efficacy for physical activity (higher influence of fathers than mothers), self-regulatory efficacy for healthy eating (higher influence of mothers than fathers), and life satisfaction (both parents had the same influence) of their adolescent children.

Later, Morton et al. (2012) distinguished between high (high levels of transformational parenting behaviours displayed by the mother and father), low (both parents show low transformational parenting), and inconsistent (one of the parents has high transformational parenting and the other low transformational parenting) transformational parenting families and their effects on healthy eating behaviours and physical activity in the leisure-time behaviours of their adolescent children. Results suggested that high transformational parenting families promote higher levels of healthy eating behaviours in their adolescent children than the other two groups (low and inconsistent transformational parenting families, which in turn, showed no differences between them). In relation to the physical activity of adolescents, differences were found in favour of high vs. low transformational parenting families, and no differences were found when comparing inconsistent transformational parenting. Thus, the authors conclude that family transformational parenting is positively associated with both healthy eating and leisure-time physical activity in adolescents.

The transformational leadership (TL) style, described in the transformational leadership theory (Bass, 1985), consists of four behaviours (called the four Is): idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration. Thus, leaders are models for behaviour and generate confidence in followers through idealized influence behaviours. Leaders expect the best from their collaborators by displaying inspirational motivation behaviours. Transformational leaders invite their followers to see reality in original ways, encouraging them to be innovative and respecting their points of view. Finally, leaders perform all these behaviours by constructing individual, personal, and worthy relations with them (individualized consideration) (Bass, 1985; Bass & Riggio, 2006).

In order to carry out their studies, Morton et al. (2011) validated the Transformational Parenting Questionnaire (TPQ), composed of 16 items. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) confirmed a four-factor model (four items each; Idealized Influence, Inspirational Motivation, Intellectual Stimulation, and Individualized Consideration), a unidimensional model (16 items), and a second-order model, which was the most appropriate. Results also showed good reliability indexes for the mother and father versions. As far as we know, the TPQ has not been translated into other languages.

The self-determination theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 1985, 2000 Ryan & Deci, 2017) distinguished between two interpersonal styles that authority figures can adopt in social contexts: autonomy support and a controlling style. Although there are many agents (i.e., coaches, teachers, parents, and peers) influencing children's development in sport contexts (e.g., Lavallee, Sheridan, Coffee, & Daly, 2019), parents are the figures with the most influence on their children's development (Assor, Roth, & Deci, 2004; Ryan & Deci, 2017). Parental autonomy support consists of parents' respectful attitude toward their children's points of view, preparing them for autonomous decision-making. Autonomy-supportive parents are empathetic and aware of their children's feelings, offering accurate information and open communication, and allowing children to make choices (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Ryan and Deci, 2000 Ryan & Deci, 2017). By contrast, controlling parenting refers to the use of manipulative and intrusive strategies, such as guilt-induction or shaming (Barber & Xia, 2013), and pressuring their children to think, feel, and act in certain ways (Grolnick, Benjet, Kurowski, & Apostoleris, 1997).According to SDT, autonomy supportive parenting provides positive developmental antecedents for children's well-being (e.g., Lekes, Gingras, Philippe, Koestner, & Fang, 2009; Vasquez, Patall, Fong, Corrigan, & Pine, 2016; Wang, Pomerantz, & Chen, 2007), whereas controlling parenting is detrimental to children's development, resulting in maladaptive developmental outcomes, such as depressive symptoms or low self-esteem (e.g., Barber & Harmon, 2002; Soenens, Park, Vansteenkiste, & Mouratidis, 2012).

The parental autonomy-supportive interpersonal style not only has beneficial effects on children, but also on the person who provides the autonomy support (Mabbe, Soenens, Vansteenkiste, van der Kaap-Deeder, & Mouratidis, 2018) and on the other parent, predicting a positive affective atmosphere at home and promoting the well-being and vitality of the other parent (Guay, Ratelle, Duchesne, & Dubois, 2018).

Research focused on parental interpersonal styles in physical activity and sport contexts has suggested that children's perceptions of autonomy support differed between mothers and fathers. In general, mothers were perceived as more autonomy-supportive than fathers (e.g., Chew & Wang, 2008). Moreover, when both the mother and father display autonomy support, the consequences are beneficial for their adolescent children's well-being (e.g., Chircov & Ryan, 2001).

Controlling social environments have been identified as an antecedent of athlete burnout (e.g., González, Tomás, Castillo, & Duda, 2017) by making athletes feel entrapped by sport. Thus, burnout-prone athletes may perceive social (e.g., parents) pressure to continue their sport involvement (Raedeke, 1997; Raedeke & Smith, 2001). Burnout has been defined as ‘a syndrome of physical/emotional exhaustion, sport devaluation, and reduced sense of accomplishment' (Raedeke, 1997, p. 398). In terms of SDT, burnout risk is intensified when authority figures do not adopt and sustain an autonomy-supportive interpersonal style. For example, in the sport domain, autonomy-supportive coaches' behaviours negatively predicted soccer players' burnout (e.g., Balaguer et al., 2012; González et al., 2017; Quested & Duda, 2011). However, as far as we know, few studies have examined the role of parents' behaviours in the development of adolescents' sport burnout. Recently, Aunola and colleagues (Aunola, Sorkkila, Viljaranta, Tolvanen, & Ryba, 2018) showed that a high level of paternal affection (warm and supportive parenting) was related to a low level of sport burnout. Results also suggested that fathers' parenting behaviours play a more important role than mothers' in student athletes' sport burnout symptoms.

Morton et al. (2012) pointed out the need to focus on transformational families and the consequences of inconsistencies in parents' transformational style for their adolescent children. The relationship between transformational parenting and autonomy support has not been studied yet. In the workplace, Wang and Gagné (2013) showed the similarities that could be established between TL and leaders' autonomy-supportive behaviours. Thus, both theories identify good practices that recognize the subordinate's perspective; both encourage creativity (TL) and self-initiative (autonomy support); and both find opportunities to mentor and become a model, recognizing individual perspectives. In this direction, Gilbert, Dagenais-Desmarais, and St-Hilaire (2017) studied the relationships between direct supervisor's TL and autonomy-supportive behaviours and employees' burnout (as a negative manifestation of health at work). Results supported a direct and positive effect of TL on autonomy support, a negative and direct effect of autonomy support on employees' burnout, and full mediation of autonomy support in the relationship between TL and burnout. In the same vein, in organizational contexts, TL was found to be a factor that reduces burnout in subordinates (e.g., Bass & Riggio, 2006; Kanste, Kyngäs, & Nikkila, 2007). Kanste et al. (2007) suggested that TL behaviours of nurse managers seem to protect them from burnout. They recommend giving the staff feedback on their performance, providing social support and individualized consideration, and developing subordinates' know-how. Recently, in educational contexts, transformational teaching was found to be a protective factor against burnout in high school teachers (Castillo, Alvarez, Estevan, Queralt, & Molina-García, 2017).

In relation to adolescents' adaptive outcomes, some authors have pointed out the need to understand the mechanisms that mediate the relationships between parenting styles and adaptive or maladaptive outcomes (Darling & Steinberg, 1993; García et al., 2018; Gracia et al., 2012; Morton et al., 2010). Few studies have examined differences between mothers' and fathers' roles in the athletic development of their children (Aunola et al., 2018; Palomo-Nieto, Ruiz-Pérez, Sánchez-Sánchez, & García-Coll, 2011). Specifically, Harrington (2006) pointed to the importance of better understanding mothers' influence on fathers' and children's leisure interests and pursuits.

In light of the literature reviewed, and given the lack of studies on transformational parenting, this study focused on four main objectives: (1) to translate the TPQ items into Spanish and examine the factor structure and reliability of the Spanish version of the TPQ; (2) to confirm the factor structure of the TPQ, examine its reliability, and provide evidence of validity based on the relationships with autonomy support; (3) to explore the relationships suggested in organizational literature between the transformational parenting style, autonomy support, and burnout, testing role differences between mothers and fathers; and (4) to test whether the different types of transformational parenting families (i.e., high, low, and inconsistent transformational parenting) differ in terms of burnout.

Method

Participants

Participants were 360 soccer players (324 males, 36 females; Mage = 16.62 years, SD = 1.11, range 12-18), representing 23 Spanish federated junior soccer teams (19 male teams and 4 female teams) that volunteered for the study.

Materials and Procedure

Players' perceptions of parents' transformational behaviours were measured using the Transformational Parenting Questionnaire (TPQ; Morton et al., 2011). The TPQ begins with the stem: ‘My father/guardian…' in fathers' version, and ‘My mother/guardian…' in mothers' version. Players were invited to complete separate TPQs for each parent/guardian (a maximum of two). The TPQ contains four subscales (each made up of four items) designed to measure idealized influence (e.g., ‘behaves as someone that I can trust'), inspirational motivation (e.g., ‘treats me in ways that build my respect for him/her'), intellectual stimulation (e.g., ‘shows respect for my ideas and opinions'), and individualized consideration (e.g., ‘shows comfort and understanding when I am upset/frustrated'). The 16 items are anchored on a 6-point Likert-type rating scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Additionally, a total score for transformational parenting was calculated by adding up the scores on the subscales, where higher scores suggest a higher level of perceived transformational parenting behaviours.

Parents' autonomy support was assessed using the supportive behaviours scale from a Spanish translation adapted for this study of the Perceived Parental Autonomy Support Scale (P-PASS; Mageau et al., 2015). The P-PASS was translated into Spanish following the back-translation procedure (Hambleton & Kanjee, 1995). This scale has 12 items divided into three subscales with four items per subscale: choice within certain limits (e.g., ‘My point of view was very important to my parents when they made important decisions about me.'); rationale for demands and limits (e.g., ‘My parents made sure that I understood why they forbid certain things.'); and acknowledgement of feelings (e.g., ‘My parents were able to put themselves in my shoes and understand my feelings.'). Items begin with the stem: ‘When I was growing up, my mother and father used to…' and the scale ranged from 1 (do not agree at all) to 7 (very strongly agree) with 4 (moderately agree) as the midpoint. Evidence of the reliability and validity of this questionnaire has been provided in previous studies (e.g., Mageau et al., 2015) and confirmed in this study. Thus, for mothers' version, the three-factor second-order model showed a satisfactory fit: χ2(51) = 58.800, p < .01, RMSEA = .066, SRMR = .060, NNFI = .942, and CFI = .955. Items' factor loadings ranged from .55 to .72, all statistically significant (p < .01), and the scales and subscales demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .66-.86, AVE = .40-.45, ρ = .73-.89). For fathers' version, the three-factor second-order model showed satisfactory fit: χ2(51) = 60.812, p < .01, RMSEA = .067, SRMR = .059, NNFI = .947, and CFI = .959. Items' factor loadings ranged from .58 to .73, all statistically significant (p < .01), and the scales and subscales demonstrated good internal consistency (α = .67-.86, AVE = .41-.45, ρ = .74-.89). A total score for "parental autonomy support" was calculated by adding up the scores on the subscales, where higher scores suggest a higher level of perceived autonomy-supportive parenting behaviours.

Burnout was assessed using the Spanish version (Balaguer et al., 2012) of the Athlete Burnout Questionnaire (Raedeke & Smith, 2001). This scale has 15 items corresponding to three different subscales (with five items each): emotional and physical exhaustion, soccer devaluation, and reduced sense of soccer accomplishment. Responses are provided on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). An example item is: "Playing football is less important to me than it used to be". For this study, a composite value for global burnout was used. Evidence of the reliability and validity of this questionnaire has been provided in the soccer context (e.g., Castillo, González, Fabra, Mercé, & Balaguer, 2012). In this study, coefficient alpha was .81.

Procedure

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the American Psychological Association (APA). Prior to conducting the study, ethical approval was obtained from the first author's institutional review board. A convenience sample was randomly selected from the web page of the Valencian Football Federation during the 2012-2013 season. Clubs were contacted first by telephone and, afterwards, in a personal interview. One of the researchers informed the people in charge of each club about the research, requesting their collaboration. All the clubs contacted participated in the research. Parents and players provided informed consent before data collection. Participation in the study was voluntary, and the questionnaires were anonymous and filled out in the club house 30 minutes before practice, during a 45-min period. Neither the coach nor the sports director was present during questionnaire administration. Researchers were present to deliver instructions to players and clarify any doubts.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Item-Factor Loading for All the Transformational Parenting Questionnaire Responses (Subsample 1, n = 170)

Note. Range 1-6.

The English version of the TPQ was translated into Spanish following the back-translation procedure widely described in the literature (e.g., Hambleton & Kanjee, 1995). First, three native Spanish speakers independently translated the original English version of TPQ into Spanish. Translation discrepancies and nuances were discussed to obtain an initial Spanish version of the questionnaire. Then, a native English translator translated the initial Spanish version into English. Next, the two English versions were compared. Finally, differences between versions were corrected. After the back-translation procedure, a pilot study was carried out to test the adequacy of the instrument for the Spanish population. No problems were found, and so this version was used as the Spanish version of the TPQ.

Data Analysis

In order to examine the factorial structure, the total sample (N = 360) was randomly split into two equivalent subsamples (Lloret, Ferreres, Hernández, & Tomás, 2014, 2017). The first subsample was composed of 170 soccer players and the second was composed of 190 soccer players.

Subsample 1 was used to test the factorial structure through exploratory factor analysis (EFA). The two versions (father and mother) were independently tested. Internal consistency was estimated in both samples through the Cronbach's alpha coefficient, average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability value (ρ). For the EFA, maximum likelihood was chosen as the extraction method, and the oblique rotation criterion was applied (Sass & Schmitt, 2010). These analyses were carried out using SPSS 20.

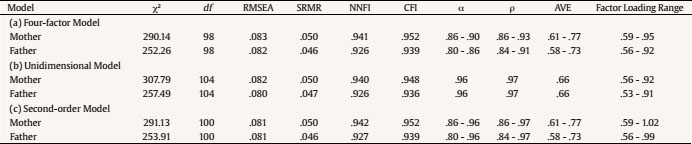

Subsample 2 was used to cross-validate the internal structure of the TPQ using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), analyse the internal consistency reliability of the scale's scores, and provide sources of validity based on relationships with perceived autonomy support. CFA were carried out with LISREL 8.80 by adopting the robust maximum likelihood to estimate model parameters. Values of NNFI and CFI ≥ .90, RMSEA and SRMR ≤ .08, and χ2/df < 5 were applied to indicate good fit. Considering the results obtained in previous studies conducted by Morton et al. (2011), three alternative models were tested for each version (mother and father): a four-factor model, a single-factor model, and a four-factor second-order model.

Table 2. Summary of Model Fit Information for All Models Tested and Reliability of Transformational Parenting Questionnaire Scales and Subscales (Mother and Father Versions) (Subsample 2, n = 190)

Note. a = Cronbach alpha; AVE = average variance extracted value; ρ = composite reliability value; (a) model composed by idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration; (b) model composed by total transformational parenting items; (c) model composed by idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration first-order factors, and transformational parenting second order factor. All indexes were significant (p < .01).

The total sample was used to test the mediation effect of autonomy support between transformational parenting and burnout in mothers and fathers using the PROCESS macro (version 3, model 4) and LISREL 8.80. Prior to this analysis, a paired-sample t-test was conducted to examine differences between mothers and fathers in transformational parenting and autonomy support.

The total sample was also used to examine the relationships between transformational parenting family groups and soccer players' burnout via extreme group comparisons. Using a quartile split procedure followed by Morton et al. (2012), parents were classified as high transformational when they scored above the 75th percentile on the TPQ, or low transformational when they scored below the 25th percentile on the TPQ. A high transformational parenting family was composed of a mother and father who both scored above the 75th percentile, a low transformational parenting family was composed of a mother and father who both scored below the 25th percentile, and an inconsistent transformational parenting family (high/low transformational parenting) consisted of one parent who scored above the 75th percentile and the other parent who scored around the 25th percentile.

Results

Descriptive Analysis and Exploratory Factor Analysis (Subsample 1)

The descriptive statistics are offered in Table 1. EFA results for both versions showed a one-factor solution that accounted for 52.9% of the common variance for fathers' version and 42.3% for mothers' version. The scale showed good internal consistency for both mother (α = .92, AVE = .42, ρ = .92) and father versions (α = .95, AVE =.53, ρ = .95).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (Subsample 2)

For both versions (mother and father), the three models tested showed satisfactory fit indexes (see Table 2). Differences between models in values of RMSEA, NNFI, or CFI were equal to or less than .002, indicating negligible practical differences (Chen, 2007; Cheung & Rensvold, 2002). Scales and subscales demonstrated good internal consistency, and items' factor loadings were all statistically significant (p < .01).

In sum, considering the results of the CFA, and according to Morton et al. (2011), the four-factor second-order model (Model c) indicated that a higher-order transformational parenting factor underlies the data, providing researchers with a transformational parenting general score and information about transformational parenting behaviours from both mother and father versions.

Table 3 shows descriptive statistics, reliability indices, and correlations among TPQ scale and subscales (mother and father versions). The four subscales were found to be highly correlated for both mother (.81> r > .76) and father versions (.84 > r > .80). These inter-factor correlations below .85 support factor discrimination (Kline, 2011).

Table 3. Descriptive Statistics, Reliability, and Pearson Correlations between Transformational Parenting Questionnaire Subscales and Total Scale (Mother and Father Versions) (Subsample 2, n = 190)

Note. Range for autonomy support scales and subscales 1-7; II = idealized influence; IM = inspirational motivation; IS = intellectual stimulation; IC = individualized consideration; TP = total transformational parenting. All correlations above .18 are significant at .05 level.

Evidence of Validity Based on Relationships with Other Variables

As expected and supporting convergent validity, results revealed a significant and positive correlation between parents' autonomy support (mother and father) and the four transformational parenting subscales (idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration) and the total score for mother and father. Pearson correlations between first-order factors ranged from .29 to .44 in mothers and from .25 to .37 in fathers (p < .01). Correlations between the total transformational parenting score and the total autonomy support score were .46 for mothers and .37 for fathers (see Table 4).

Table 4. Descriptive Statistics, Reliability, and Pearson Correlations of Transformational Parenting Questionnaire Subscales and Total Scale with Autonomy Support (Mother and Father) Scales and Subscales (Subsample 2, n = 190)

Note. Range for autonomy support scales and subscales 1-7; II = idealized influence; IM = inspirational motivation; IS = intellectual stimulation; IC = individualized consideration; TP = total transformational parenting. All correlations above .18 are significant at .05 level.

Testing for Mediation Effects

Before testing the mediation effects, a Pearson's correlation analysis was conducted with transformational parenting (mother and father), autonomy support (mother and father), and players' sport burnout (see Table 5). As expected, a positive correlation was found between transformational parenting and autonomy support, and negative relationships between these variables and burnout, for both mothers and fathers.

Table 5. Descriptive Statistics, Reliability, and Pearson Correlations between Transformational Parenting Questionnaire, Autonomy Support (Mother and FatherVersions) and Soccer Players Burnout (n = 360)

Note. Transformational parenting range 1-6; autonomy support range = 1-7; burnout range = 1-5; α = Cronbach alpha. All correlations were significant at p < .01.

Additionally, a paired-samples t-test was conducted to examine differences between mothers and fathers in transformational parenting and autonomy support. Results indicated that there were differences between mothers and fathers in transformational parenting behaviours (t = 3.62, p < .01), but no differences in autonomy support behaviours (t = 0.74, p = .46). Players perceived that their mothers exhibited more transformational behaviours than their fathers.

Analyses testing whether autonomy support would mediate the relationship between the perceived transformational parenting style and players' burnout (see Figure 1) revealed a significant association between mothers' perceived transformational parenting style and mothers' autonomy support. The association between mothers' autonomy support and players' burnout also showed a significant regression weight. The association between mothers' perceived transformational parenting style and burnout, controlling for mothers' autonomy support, was significant. The bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method showed that mothers' autonomy support partially mediated the indirect association between mothers' transformational parenting and burnout (IE = -.05, SE = .02, 95% CI = [-.11, -.01]).

Figure 1. Parent Autonomy Support Mediated the Relationship between Perceived Transformational Parenting and Burnout.N = 360. Values are regression coefficients.*p < .05, **p < .01.

The results also showed a significant association between fathers' perceived transformational parenting style and fathers' autonomy support. The association between fathers' autonomy support and players' burnout showed a non-significant regression weight. The association between fathers' perceived transformational parenting style and burnout, controlling for fathers' autonomy support, was not significant. The bias-corrected percentile bootstrap method showed that fathers' autonomy support did not mediate the indirect association between fathers' transformational parenting style and burnout (IE = -.02, SE = .02, 95% CI = [-.07, .01]) (see Figure 1).

An additional mediation test considering the effect of both mothers' and fathers' transformational parenting and autonomy support on players' burnout was conducted. The model presented an adequate fit to the data: χ2(2) = 4.51, p > .05, CFI = .994, NNFI = .970, RMSEA = .074, SRMR = .059. Results showed a positive and significant association (p < .01) between transformational parenting and autonomy support for mothers (β = .31) and fathers (β = .28), as well as a negative and significant association between mothers' autonomy support and burnout (β = -.33). The association between fathers' autonomy support and burnout was not significant (β = .16, p > .05). Direct effects of transformational parenting (mother and father) on burnout were not significant (β = -.13 and -.08, respectively, p > .05). The indirect effect of mothers' transformational parenting on burnout via autonomy support was negative and significant (IE = -.10, p < .05), whereas the indirect effect of fathers' transformational parenting on burnout via autonomy support was not significant (IE = .05, p > .05). Results confirm that mothers' autonomy support totally mediated the relationship between transformational parenting behaviours and burnout.

Additionally, a modulation test was conducted using the PROCESS macro (Model 1) to study the role of mothers' transformational parenting in the relationship between fathers' transformational parenting and players' burnout. Results showed a significant interaction between mothers' and fathers' transformational parenting (β = -.07, t = -2.48, p < .01) (see Figure 2). When mothers' transformational parenting levels were high (> 4.01 on the 1-6 scale), fathers' transformational parenting was negatively and significantly associated with burnout, but when mothers' transformational parenting levels were < 1.21 on the 1-6 scale, fathers' transformational parenting effects on burnout were not significant.

Extreme Group Family Comparisons

Three one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) were computed to examine whether the three groups differed in terms of gender, age, and burnout variables. Results indicated that there were no differences in gender, F(2, 73) = 0.772, p = .466, or age between the three groups, F(2, 73) = 0.339, p = .714. However, the three groups differed in burnout, F(2, 73) = 4.466, p = .015, η2 = .11. Significant pair-wise comparisons (p = .04) were obtained between the high transformational parenting family group (n = 35, M = 1.78, SD = 0.49) and the low transformational parenting family group (n = 37, M = 2.06, SD = 0.48). No significant differences were observed (p = .57) between the high transformational parenting family group (M = 1.78) and the inconsistent family group (high-low transformational parenting) (n = 4, M = 1.53, SD = 0.17), and between the low transformational parenting family group (M = 2.06) and the inconsistent family group (M = 1.53, p = .09). That is, players who perceived that their families displayed the highest levels of transformational parenting behaviours (high transformational parenting group) displayed lower levels of burnout than players who perceived that their families displayed the lowest levels of transformational parenting behaviours (low transformational parenting group). Players who perceived that their families displayed inconsistent levels of transformational parenting behaviours (high-low transformational parenting group) did not differ in terms of burnout from those in either the high transformational parenting or the low transformational parenting group.

Discussion

One of the objectives of this research was to translate the Transformational Parenting Questionnaire (TPQ; Morton et al., 2011) into Spanish and examine the psychometric properties of both mother and father versions in junior soccer players. Specifically, the factorial structure, reliability, and validity, based on the relationship with autonomy support variables, were tested. Results showed good psychometric properties for the Spanish version of the TPQ in adolescent soccer players.

CFA results indicated that the four transformational parenting dimensions (idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration), contributing to a higher-order factor called transformational parenting, adequately reflect the underlying factor structure of the TPQ, which is similar to Morton et al's (2011) results. The three models tested (four-factor, one-factor, and second-order model) offered good fit indexes. Taking previous transformational leadership literature into account (e.g., Álvarez et al., 2018), this solution offers researchers all three alternatives, depending on the aim of the study.

As in previous studies in other contexts (Gilbert et al., 2017), soccer players' perceptions of their parents' transformational behaviours were positively related to autonomy support by mothers and fathers. That is, when parents display transformational behaviours, they also display autonomy supportive behaviours, which confirms the similarities between transformational parenting and autonomy supportive behaviours proposed by Wang and Gagné (2013). Thus, parents' behaviours that establish limits but respect a child's point of view and interests and encourage his/her decision-making ("choice with certain limits") as well as parent-child interactions built on fair and open communication, explaining the rationale for the child's limits and duties (rational demands and limits), seem to be quite similar to individual consideration and intellectual stimulation. Finally, parents who are capable of understanding their children's feelings, discussing different points of view, and encouraging their children to be themselves ("acknowledgement of feelings") are very close to exhibiting inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration.

Previous general literature on transformational leadership suggested that women are frequently perceived as more transformational than men (e.g., Eagly, Johannesen-Schmith, & van Engen, 2003). Our study confirmed this gender difference between mothers and fathers. With regard to autonomy support, and contrary to previous research (e.g., Chew & Wang, 2008), in our study there were no differences between mothers and fathers, suggesting that players perceived that both their father and mother supported their autonomy.

Researchers noted the need to clarify the mechanisms that mediate between parenting styles and adolescents' adaptive outcomes (Darling & Steinberg, 1993; García et al., 2018; Gracia et al., 2012; Morton et al., 2010), and analyse possible differences in mothers' and fathers' roles in their children's sport development (e.g., Palomo-Nieto et al., 2011). Bearing this in mind, we tested the mediation effect of autonomy support between transformational parenting behaviours and burnout (in this case a maladaptive outcome) in mothers and fathers (separately and together), and we explored differences between families displaying high- low- and inconsistent transformational parenting behaviours in relation to burnout. When mediation was tested separately, the mediation of autonomy support and the direct effect of transformational parenting behaviours on burnout were confirmed for both mother and father versions. These results provide additional evidence for the validity of TPQ mother and father versions.

In addition, when testing families, our results suggest a negative and significant association between transformational parenting and burnout, partially mediated by autonomy support by mothers, but not by fathers, and a positive and significant association between transformational parenting and autonomy support by mothers and fathers. Thus, our results suggest an impact of mothers' autonomy support on their adolescent children's burnout, which did not exist for fathers. Our results are aligned with previous research suggesting that perceptions of an autonomy-supportive environment contributed to reducing players' burnout (e.g., González et al., 2017), and reinforce results revealing that adolescent players perceived that their mothers play a differential role in their sport development (Palomo-Nieto et al., 2011).

In relation to autonomy support, our results also suggest a major role of the mother over the father in explaining their children's burnout, when mothers' and fathers' transformational parenting behaviours were considered together. Therefore, mothers' autonomy support is the only factor that is negatively associated with athletes' burnout. These results invite us to explore whether there was an interaction effect between transformational parenting behaviours of mothers and fathers. Modulation effects showed that when mothers' transformational parenting levels were high, fathers' transformational parenting was significantly and negatively associated with children's burnout, but when mothers' transformational parenting levels were low, the effects of fathers' transformational parenting on children' burnout disappeared. Mothers' role had been identified as a catalyser of the father-child relationship (Harrington, 2006). As Palomo-Nieto et al. (2011) pointed out, mothers have a central role in their children's emotionality, which makes them largely responsible for the psychological and social support of their children (e.g., Pedro, Altafim, & Linhares, 2017).

Furthermore, comparing high-, low- and inconsistent transformational parenting families in relation to burnout, our study suggests that when both parents are highly transformational, their adolescent children feel less burnout. By contrast, adolescent children from families with two low-transformational parents are more prone to suffering burnout. In relation to the fact that the differences are not significant when comparing high- and low- transformational parenting families to inconsistent families (one of the parents is high-transformational and the other is low-transformational), we understand that this result is due to the low number of inconsistent families in our sample. In previous research, high transformational families were positively associated with healthy behaviours (healthy eating and leisure-time physical activity) compared to low transformational families, and similar to our study, differences between inconsistent and low or high families were not significant when associated with physical activity practice (Morton et al., 2012).

Parents become a model through which children can learn and adopt values, beliefs, and behaviours. Morton et al. (2010) highlighted the relationships between parental styles and transformational parenting behaviours, arguing that what the literature supports as a successful parenting style matches transformational parenting behaviours. Thus, parents have the chance to create effective role modelling (idealized influence) and highly realistic and optimistic expectations (inspirational motivation) for their children. Moreover, fluid and open-minded parent-child communication is respectful of the adolescent's points of view, promoting a critical way of thinking (intellectual stimulation) and being more sensitive to the child's needs and abilities (individual consideration). In this study, our results confirm the similarities between transformational parenting and autonomy support mentioned by Wang and Gagné (2013), and suggest that displaying high levels of transformational parenting behaviours would be sufficient to reduce sport burnout in adolescents, keeping in mind that it is highly likely that if parents display transformational parenting behaviours, they will also display autonomy supportive behaviours.

Several contributions and conclusions can be drawn from this study. First, the TPQ is applicable to the population of Spanish adolescent athletes. Second, transformational parenting behaviours promote autonomy support in mothers and fathers. Third, transformational parenting behaviours prevent sport burnout in adolescent soccer players. Fourth, when both parents display high transformational parenting behaviours, their children suffer less burnout in sport.

Some limitations of this study include the fact that the population represented in this study (Spanish federated soccer players) is not gender-balanced (reflecting the gender balance of the universe represented), which makes it difficult to perform analyses by gender (invariance study or results comparison). The information was obtained through self-reported measures, and the cross-sectional design of the study suggests that the results should be interpreted with caution.

Practical Implications

In order to contribute to reducing the chance of adolescents suffering burnout in sport, and in light of our study, some practical implications and recommendations can be suggested for practitioners who work with parents of adolescent athletes. In order to reduce burnout in adolescent athletes, parents have to be aware that their behaviours become a model that inspires their children, influencing them by ‘walking the talk'. It is very important to have open communication with children, which implies both explaining the limits (necessary for an adolescent's well-adjusted development) and hearing adolescents' points of view, opinions, and arguments, by displaying mutual respect. Finally, it is important to provide athletes with opportunities to choose their sport practices, recognizing athletes' needs and feelings, and enhancing creativity and engagement in things that are important to them.