The eleventh revision of the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-11) was approved by the World Health Assembly in May 2019, the governing body of the World Health Organization (WHO, 2019), and took effect as the basis for reporting health statistics to WHO by its member states in 2022 (WHO, 2022). For nearly three decades, the ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders has been the most widely used classification of mental disorders worldwide (Reed et al., 2011), and it is expected that this will also be the case with the ICD-11. WHO's Department of Mental Health and Substance Use has developed Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Requirements (CDDR) for ICD-11 Mental, Behavioural or Neurodevelopmental Disorders (see https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/). Like the similar product developed for ICD-10, called the Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines (CDDG; WHO, 1992), the purpose of the CDDR is to provide sufficient information for reliable implementation of the diagnostic classification in clinical settings.

The ICD-11 includes a grouping of "paraphilic disorders", which in the ICD-10 were referred to as "disorders of sexual preference" (Krueger et al., 2017). Paraphilic disorders are characterized by atypical patterns of sexual arousal in which: a) the arousal pattern is intense, sustained, and manifested by sexual thoughts, fantasies, urges, and/or behaviours; b) the focus of the arousal pattern involves others whose age or status renders them unwilling or unable to consent (e.g., children, animals, unsuspecting individuals being viewed through a window); and c) the individual with the arousal pattern has acted on these urges, fantasies, or thoughts or is markedly distressed by them (Krueger et al., 2017). The ICD-11 CDDR for paraphilic disorders specify that atypical patterns of sexual arousal should not be considered mental disorders merely because they deviate from social or cultural norms. The named ICD-11 paraphilic disorders are the exhibitionistic disorder, the voyeuristic disorder, the pedophilic disorder, the coercive sexual sadism disorder, and the frotteuristic disorder. The category "other paraphilic disorder involving non-consenting individuals" may be used for other arousal patterns that meet the general diagnostic requirements for paraphilic disorders but are not specifically named (e.g., arousal patterns involving corpses or animals). Fetishism, fetishistic tranvestism, and sadomasochism are no longer included as paraphilic disorders. However, the category "paraphilic disorder involving solitary behaviour or consenting individuals" may be used if the individual is markedly distressed by an atypical arousal pattern that does not involve non-consenting individuals and the distress is not simply due to actual or feared social rejection, or when behaviour related to the arousal pattern poses a significant risk of injury or death for the individual or their partner. The specified diagnostic requirements are intended to identify appropriate targets for health services and public health reporting, rather than simply describing atypical sexual behaviours (Reed et al., 2016).

In many countries, the diagnosis and treatment of paraphilic disorders are extensively entangled with the criminal justice systems and policies that regulate sexual behaviour and criminal status (First & Halon, 2008; Saleh et al., 2009). It is generally established that an individual's state of awareness of the nature or quality of their actions is a assigning factor for establishing criminal responsibility for individuals diagnosed with a mental disorder, and paraphilic disorders are not an exception (Abdalla-Filho et al., 2019; Briken & Muller, 2014; Briken et al., 2019; Dobbrunz et al., 2020; Makhlouf et al., 2020; Martínez-López et al., 2019). Although sexual crimes may occur in the context of a paraphilic disorder, particularly when the individual acts upon the paraphilic arousal, many sexual crimes involving non-consenting individuals reflect transient, impulsive, or opportunistic acts rather than sustained, persistent patterns of sexual arousal. Therefore, the commitment of a criminal act in the absence of an accompanying sustained pattern of sexual arousal is not on its own enough to meet the diagnostic requirements for a paraphilic disorder (Krueger et al., 2017).

Our previous research has demonstrated that clinicians can adequately weigh the multiple relevant factors necessary to apply the ICD-11 diagnostic requirements for paraphilic disorders (Keeley et al., 2021). However, we also found that clinicians (primarily psychiatrists and psychologists) tended to over-pathologize non-disordered but atypical sexual behaviours and preferences. Overdiagnosis of paraphilic disorders is potentially quite serious because of legal consequences such as civil commitment and extensive mandatory treatment, as well as limitations on daily activities such as employment or place of residence (Briken & Krueger, 2018). Furthermore, ethical clinical practice involving the diagnosis and management of individuals with paraphilic disorders requires that mental health professionals ensure a patient's autonomy in making voluntary decisions, avoiding harm, and ensuring that the welfare of the individual is the primary goal of treatment (Glaser, 2002).

General stigma against mental disorders is a widespread problem with adverse consequences for the individual, creating barriers to seeking and receiving adequate health care (Corrigan, 2004), but stigma is especially intense regarding paraphilic disorders. The general public holds substantially negative attitudes towards individuals who are sexually attracted to children; people often report they wish such individuals to be dead or incarcerated, even if they have not acted on their sexual urges (Jahnke et al., 2015a). Waldura et al. (2016) reported that individuals who participated in consensual sexual behaviours such as bondage, domination, submission, sadism, or masochism (which are not considered paraphilic disorders in ICD-11) were afraid to discuss their sexuality in health care settings and could sense disapproval from their clinicians. Although mental health professionals generally have more positive attitudes toward people with a mental illness, they may display negative attitudes toward individuals who engage in atypical sexual behaviours or who have paraphilic disorders and may be reluctant to assess and treat these patients (Jahnke et al., 2015b; Stiels-Glenn, 2010).

Stigmatization and pathologization appears to vary based on the gender of the target indivuals. One study found that mental health professionals rated vignettes describing female subjects with exhibitionistic, frotteuristic, sexual sadistic, and pedophilic behavior as less psychopathological than male subjects but stigmatized female subjects more. On the other hand, female sexual behavior that fulfilled diagnostic requirements for masochistic disorder were described as more pathological (Fuss et al., 2018). Because paraphilic disorders may be associated in the mind of the public with criminality, dangerousness, and aggressive behaviours (Imhoff & Jahnke, 2018), negative attitudes may be more pronounced among women clinicians because women are more frequently victims of sexual aggression, generally experience a higher risk of being a victim of violence, and are more likely to experience fear of violence. According to WHO (2021), one in three women (aged 15-49 years) has been the victim of physical and/or sexual violence. Therefore, women may be more likely to perceive the behaviour of men as being aggressive or threatening (Domínguez-Martínez et al., in press; Hinkelman & Granello, 2003; Robles-García et al., 2020; Stuart & Arboleda-Flores, 2001), and may be more likely to view aggressive or threatening behaviours as criminal.

In health care settings in many countries, there is generally a lack of specific health services or clinical guidance available for the treatment of paraphilic disorders, and health care professionals are unlikely to have specific training that gives them appropriate knowledge and skills in treating paraphilic disorders (Martínez-López et al., 2019). This is true even though paraphilic disorders are not necessarily associated with criminal offenses (Thibaut et al., 2010). For example, patients with paraphilias may present for treatment due to the associated distress in their personal lives or out of fear that they might commit an offense and wish to prevent it. However, even if a patient does nothing more than discuss impulses to act on a paraphilic arousal pattern not involving criminal behaviour, clinicians may communicate negative attitudes based on their own preconceptions about patterns of sexuality and lack of knowledge about the non-causal relation between paraphilic disorders and crime. The ICD-10 CDDG may have contributed to this pathologization by not including clear and uniform criteria for paraphilic disorders. While relatively more elaborated guidance is provided for some categories (e.g., fetishism, paedophilia), information for other categories is limited to little more than a description of the paraphilic behaviour (e.g., fetishistic transvestism, voyeurism) and particularly fail to distinguish non-pathological variants of the arousal patterns. Therefore, it is reasonable to hypothesize that stigmatization and pathologization of atypical sexual behaviours contribute to their overdiagnosis and criminalization.

Given the important distinction made in the ICD-11 between paraphilic disorders and private sexual behaviours involving atypical foci of sexual arousal that do not have appreciable public health impact and for which treatment is not indicated (Reed et al., 2016), the present study aimed to identify whether clinicians' gender, clinical experience, and personal attitudes influenced their perception of: a) the criminality of specific sexual behaviours; b) if so, whether the individual having a mental disorder (i.e., a paraphilic disorder) should be considered in assigning the extent of a person's criminal responsibility; and c) the need for mandatory treatment as a part of criminal sentencing if a crime related to sexual behaviour was perceived to have been committed in the context of a paraphilic disorder.

The present study was part of a larger study (Keeley et al., 2021) aimed at examining clinicians' ability to accurately apply the ICD-11 diagnostic requirements for paraphilic disorders to standardized case vignettes that were manipulated in particular dimensions related to paraphilic disorders. These included: a) strength and intensity of the arousal pattern (frotteuristic interest); b) the extent to which the other person consented to participate in the sexual act (coercive sexual sadism); c) the degree to which the person acted on the arousal (exhibitionistic arousal pattern); d) the amount of distress experienced by the person in the context of acting on a paraphilic arousal pattern that does not involve non-consenting individual (fetishistic arousal pattern); and e) the degree to which there was a risk of injury or death related to a consensual paraphilic behaviour (masochistic arousal pattern). The present study focuses specifically on features related to judgments about criminality. Therefore, we examined those diagnoses from the larger study in which acting on the arousal pattern is most likely to involve the commission of a crime given that rubbing one's genitals against an unsuspecting person (frotteuristic disorder), inflicting psychological or physical suffering on an unwilling person (coercive sexual sadism disorder), and exposing one's genitals to unsuspecting individuals without their consent (exhibitionistic disorder) are generally considered to be criminal acts.

Method

Participants

Participants were members of the Global Clinical Practice Network (GCPN) who indicated advanced proficiency or fluency in English, Spanish, or Japanese (the languages in which the study was carried out) and who were seeing patients in a clinical setting or supervising the clinical work of others at the time of the study (see Keeley et al., 2021). The GCPN is an international, multidisciplinary, and multilingual research network of mental health professionals who joined the network to participate in field testing of the ICD-11 classification of mental disorders (Reed et al., 2015).

Materials

For the present analysis, only two vignettes from the larger study (Keeley et al., 2021) for each included paraphilic disorder (frotteuristic disorder, coercive sexual sadism disorder, and exhibitionistic disorder) reflecting the relevant dimensions of ICD-11 were used (i.e., a total of 6 vignettes). Each vignette represented the least or most extreme levels of a dimension: for the "frotteuristic disorder", the vignettes varied according to the intensity and persistence of the person's "arousal". The least extreme vignette portrayed accidental and unintentional arousal of an individual that otherwise held normative sexual interests while the most extreme vignette described an individual with an exclusive, sustained, and intense arousal focused on frotteuristic acts that the subject sought to carry out intentionally. For the "coercive sexual sadism disorder", the vignettes varied in the degree to which the person was specifically aroused by the "lack of consent". The least extreme vignette reflected consensual sexual sadism with simulated but controlled coercive acts while the most extreme vignette described exclusive, sustained, and intense arousal focused on the infliction of physical or psychological suffering on a non-consenting person. The least extreme vignette for the "exhibitionistic disorder", representing the degree to which the person had "acted" on his interests, described an individual that held normative sexual interests with exhibitionistic fantasies who had never acted on those fantasies, and in the most extreme vignette the individual intentionally planned and sought situations in which to expose his genitals. Beyond the manipulated dimension, the vignettes for each disorder were identical and depicted heterosexual males to avoid biases that might be triggered in the raters related to the individual's gender or sexual orientation (Fuss et.al., 2018) The least extreme vignette for all diagnoses did not meet the diagnostic requirements for any paraphilic disorder while the most extreme vignette, in addition to meeting the full diagnostic requirements of the relevant paraphilic disorder, also depicted a sexual crime.

Procedure

Members of the GCPN were invited to participate in the study through an email that contained the link to the online platform for the study. GCPN members had provided a range of demographic information, including region, gender, age, profession, and years of clinical experience) as a part of enrollment in the GCPN. After consent information was provided and accepted, the ICD-11 diagnostic requirements for paraphilic disorders were presented. For the larger study, participants were randomly assigned to view four vignettes, one for each arousal pattern, with severity level for each arousal pattern randomly assigned. Given that in the current study we used only the least and most extreme vignettes for three arousal patterns, a total of six vignettes were used. Participants may have completed one to three of these vignettes or may not have seen any of them due to the nature of the randomization. For the present analysis, we included participants who completed at least one of these six vignettes.

After reading each vignette, participants were asked if the person described in the vignette met diagnostic requirements for a paraphilic disorder and whether a crime had been committed. If the participant indicated the presence of a crime, two additional questions were asked: (a) "To what extent should the fact that he has a mental disorder be considered in assigning the extent of his criminal responsibility (e.g., through an ‘insanity defense')?", rated on a Likert-type scale from 1 (not at all) to 7 (a great deal); and (b) "If the person in the vignette were convicted of a crime based on the sexual behaviour described, should he be required to undergo treatment related to his sexual arousal patterns as a part of his sentence?". The subject in all vignettes was a heterosexual male to avoid variation related to gender and sexual orientation in attributions about psychopathology and criminality that was extraneous to the study.

After finishing the vignettes ratings, participants rated a set of statements about their attitudes, assessed in a Likert agreement scale from 1 = totally disagree to 5 = totally agree, on: (a) "It is not appropriate for a mental disorders classification to attempt to differentiate between normal and abnormal patterns of sexual arousal as a basis for defining mental disorders"; (b) "Any intense pattern of sexual interest other than sexual interest in genital stimulation or preparatory fondling with phenotypically normal, physically mature, consenting human partners should be considered abnormal"; and (c) "An atypical pattern of sexual interest should be considered a mental disorder only if it causes distress or impairment, or significant risk of harm to the self or others, or leads to behaviour that violates the rights of others".

Data Analysis

For the comparison between men and women, chi-square (χ2) and independent sample t-tests were used. Data are presented in frequencies and percentages or means and standard deviations where appropriate.

Multivariate logistic regression models for each diagnosis were performed for the outcome variables of "commission of a crime" and "need for treatment related to a crime involving sexual behaviour". For the outcome of "whether the mental disorder diagnosis should be considered in assigning criminal responsibility", an ordinal regression model was used. Clinicians' gender was used as an independent variable while attitudes were included as covariates. Current age, years of experience, vignette severity, identification of correct diagnosis, and the number of diagnoses assigned to each vignette were included in the model. For the logistic models, the Hosmer/Lemeshow test was used to determine goodness of fit and for the ordinal model, the parallel regression assumption was determined. Then backward elimination was used to identify the most explanatory and calibrated model. Odds ratios and confidence intervals (95%) are presented for these models. Alpha values were deemed significant at a p < .05.

Results

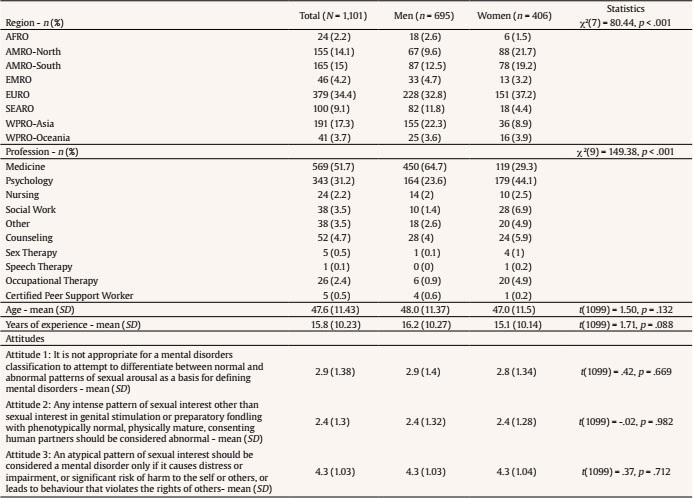

A total of 1,101 members of the GCPN met the criteria to be included in the analysis. A higher proportion of men (63.1%, n = 695) than women (36.9%, n = 406) participated in the study. Men were more likely to be physicians (64.7%, n = 450 vs. 29.3%, n = 569), while women were more likely to be members of other health professions, particularly psychology (44.1%, n = 179 vs. 23.6%, n = 164, p < .001). As shown in Table 1, no other demographic or attitude differences by gender were found among the participants.

Both men and women leaned towards a neutral position (neither agree nor disagree) regarding the statement "It is not appropriate for a mental disorders classification to attempt to differentiate between normal and abnormal patterns of sexual arousal as a basis for defining mental disorders." They leaned more toward disagreement with the statement "Any intense pattern of sexual interest other than sexual interest in genital stimulation or preparatory fondling with phenotypically normal, physically mature, consenting human partners should be considered abnormal". Participants somewhat or strongly agreed with the statement "An atypical pattern of sexual interest should be considered a mental disorder only if it causes distress or impairment, or significant risk of harm to the self or others or leads to behaviour that violates the rights of others".

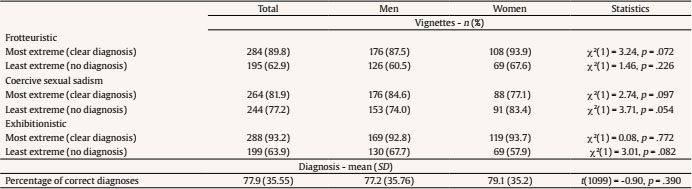

No differences between men and women were found in the percentage of correct diagnosis assigned to each vignette (diagnosis of the corresponding paraphilic disorder in the most extreme vignette and no diagnosis in the least extreme vignette), which was over 75% overall for both genders (see Table 2). However, across men and women, diagnostic accuracy was lower with the least extreme vignette (68.1%) compared to the most extreme vignette (88.3%), χ2(1) = 112.75, p < .001, indicating a tendency to overdiagnose non-pathological expressions of atypical arousal patterns.

Table 2. Correct Diagnosis Assessed by Clinicians according to the Vignette's Level of Description (most and least extreme) by Gender

Commission of a Crime

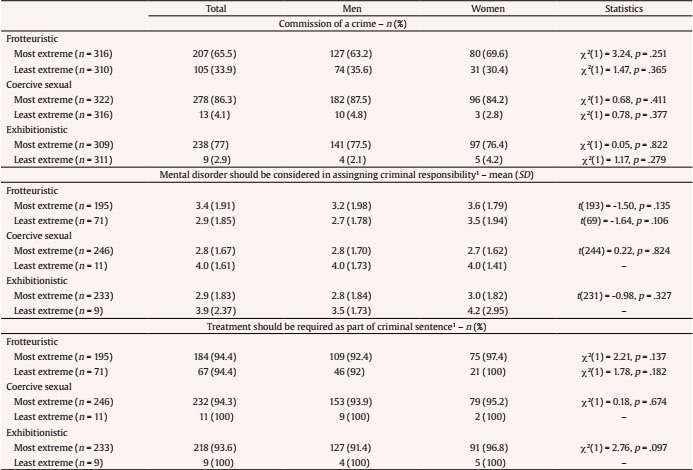

No differences were found in the frequency with which men and women clinicians asserted that a crime was committed in the vignette description for the three paraphilic disorders (see Table 3). For coercive sexual sadism disorder and exhibitionistic disorder, more than 75% of the participants identified the commission of a crime in the most extreme vignette and less than 5% considered that a crime had been committed in the least extreme vignette. Participants were more confused about frotteuristic disorder. Less than 70% of participants, including both men and women, perceived the commission of a crime in the most extreme vignette and more than 30% of both men and women considered a crime had been committed in the least extreme vignette.

Table 3. Agreement that the Behavior Described in the Vignette Constituted a Crime, that the Presence of a Paraphilic Disorder Should Be Considered in Assigning Criminal Responsibility and that Treatment Should Be Required as a Part of Criminal Sentence, by Gender

Note.In the Statistics column, a hyphen (-) means that there are not enough participants to perform an adequate comparison.

1Asked only of those clinicians who said a crime had been committed.

In the logistic model shown in Table 4, the most important predictor of clinicians' determination of the commission of a crime was the severity of the disorder (defined by the least and most extreme vignette) described in the assessed vignette. Clinicians recognized the commission of a crime in the most extreme vignettes. Whether the paraphilic disorder was diagnosed correctly did not affect clinicians' determination of a crime committed for the coercive sexual sadism and exhibitionistic vignettes. Nevertheless, for the frotteuristic vignette, the odds of perceiving the commission of a crime with an incorrect frotteuristic disorder diagnosis were less than with a correct diagnosis (p < .001, 95% CI [.15, .38]). It seems that for some participants, the description of unintentional rubbing behaviour and related arousal were perceived as a crime. The variance in perceiving the commission of a crime explained by vignette severity (see Table 4) was much lower for frotteuristic disorder (20%, according to the Nagelkerke's R2 value) than for coercive sexual sadism disorder (74%) and exhibitionistic disorder (67%).

Consideration of a Paraphilic Disorder Diagnosis in Assigning Criminal Responsibility

As seen in Table 3, clinicians who asserted that the person had committed a crime based on his sexual behaviour tended not to agree that the person's paraphilic disorder should be considered in assigning criminal responsibility (e.g., through the "insanity defense"); in other words, they perceived the person to be criminally liable for his actions. However, their conviction in this belief was mild, as the ratings hovered near the mid-point of the rating scale. Male and female clinicians did not differ in their ratings on this item. The regression model for the frotteuristic disorder vignettes shows that: a) older vs. younger clinicians (p < .05, 95% CI [1.009, 1.08]), b) women vs. men clinicians (p < .05, 95% CI [1.07, 2.66]), and c) a higher agreement considering the basis for defining a sexual pattern as a mental disorder (p < .05, 95% CI [1.003, 1.53]), were more likely to advocate considering the disorder in assigning criminal responsibility (see Table 4). The latter was also observed for exhibitionistic disorder (p < .05, 95% CI [1.02, 1.56]). Independent of whether a crime had been clearly committed, as described in the most extreme vignettes (which was not predictive of ratings indicating that a mental disorder should be considered in assigning criminal responsibility), the attitudes that mental disorders should be diagnosed based on "significant risk of harm to self and others" was also associated with saying that the diagnosis should be considered in assigning criminal responsibility for frotteuristic and exhibitionistic disorder. Further, a higher agreement that any intense pattern of sexual interest other than sexual interest in genital stimulation or preparatory fondling with phenotypically normal, physically mature, consenting human partners should be considered abnormal was associated with the agreement that a diagnosis of exhibitionism should be considered in assigning the extent of criminal responsibility (p < .05, 95% CI [1.03, 1.46]). None of the variables included in the regression model were predictors for the consideration of a mental disorder diagnosis of coercive sexual sadism in assigning the extent of criminal responsibility. However, the variance explained for this outcome was low for all three disorders (less than 10%).

Need for Treatment Related to Sexual Arousal Pattern if Charged for a Crime

Almost all participants who thought a crime had been committed in the vignette felt that treatment should be required as a part of criminal sentencing if the person were convicted (Table 3). This was also observed in the least extreme vignettes, where essential diagnostic requirements for a paraphilic disorder were not met. In the logistic regression model for frotteuristic disorder, the odds of indicating a need for treatment if charged with a crime in the most extreme vignette were lower (p < .05, 95% CI [.005, .79]). In addition, for this disorder, the most important predictors for the saying that treatment should be required as a part of criminal sentencing was that the attitude of considering abnormal any intense pattern of sexual interest other than sexual interest in genital stimulation or preparatory fondling with phenotypically normal, physically mature, consenting human partners (p < .05, 95% CI [1.13, 3.79]) and a correct diagnosis of the disorder (p < .01, 95% CI [1.24, 119.79]). This attitude also predicted the perceived need for treatment as a part of criminal sentencing for coercive sexual sadism disorder (p < .05, 95% CI [1.23, 5.54]).

Discussion

In the present study, more than 75% of the clinicians were capable of correctly discriminating between sexual inclinations that did not warrant a diagnosis of a mental disorder from paraphilic disorders using the ICD-11 diagnostic requirements. There was evidence of a general tendency to overdiagnose cases with paraphilic arousal patterns that did not meet the diagnostic requirements of paraphilic disorder. Clinicians generally were able to accurately identify the depiction of a crime in the most extreme vignette; the severity of the vignette was the most important predictor of whether clinicians reported that a crime had been committed.

The identification of crime in the most extreme vignettes may reflect the awareness of most clinicians of criminal laws in their countries, where a crime is generally conceived of as a consequence of the perpetrator's behaviour rather than the presence of a paraphilic disorder. There is nothing in the ICD-11 diagnostic requirements for paraphilic disorders that suggests that individuals with paraphilic disorders who commit sexual crimes associated with their paraphilic arousal pattern should not be considered to be criminally responsible for their behavior (Krueger et al., 2017). Legal analyses of the impact of the ICD-11 classification of paraphilic disorders in four of the five countries where they were conducted—Brazil (Abdalla-Filho et al., 2019), Lebanon (Makhlouf et al., 2020), Mexico (Martínez-López et al., 2019), and South Africa (Artz et al., 2021)—found no basis for such a claim in any of their respective legal systems. In most countries, having a paraphilic arousal pattern or disorder is not a criminal offense; however, an action that a person takes in response to their sexual arousal may be punishable by law (Makhlouf et al., 2020). In Germany, however, having a paraphilic disorder may impact on legal judgments of criminal responsibility for sexual acts related to the paraphilic arousal pattern (Briken et.al., 2019). The ICD-11 paraphilic disorders classification is in part intended to identify opportunities for appropriate treatment that may reduce criminal behaviour motivated by sexual arousal patterns in paraphilic disorders (Krueger et al., 2017). Moreover, it may have an impact on suggesting modifications of criminal laws or policies that may create barriers to treatment for paraphilic disorders in the absence of criminal behaviour (Martínez-López et al., 2019).

For the frotteuristic disorder vignettes, more than 30% of the participants considered that a crime had been committed in the least extreme vignette, where sexual arousal was accidental and unintentional, and no criminal behaviour was described. This suggests that it is important to examine the boundaries clinicians are using to distinguish between pathological and non-pathological sexual behaviour (Moser, 2009; Moser & Kleinpatz, 2006; Shindel & Moser, 2011). Consent and action (the dimensions that varied for coercive sexual sadism disorder and exhibitionism, respectively) may represent a clearer boundary between criminal and non-criminal behaviour. Arousal may be a vaguer boundary and inherently requires a more complex judgment because thoughts cannot be observed directly and are most typically inferred from behavior. These results highlight the need for clinical training in the ICD-11 approach to the diagnosis of paraphilic disorders (Keeley et al., 2021) and the need for examination of laws and policies affecting clinician behavior as they relate to paraphilic disorders (e.g., settings in which treatment is permited, mandatory reporting) to support the provision of appropriate treatment and avoid misidentification of criminal behavior in persons with paraphilic disorders or atypical sexual arousal patterns.

This study found an influence of gender and personal attitudes on the evaluation of vignettes depicting paraphilic arousal patterns or disorders. We found women participants (for frotteuristic disorder) and participants who endorsed the view that any atypical pattern of sexual interest should be considered abnormal (for exhibitionistic disorder) were more likely to endorse requiring treatment as a part of criminal sentencing. Dobbrunz et al. (2021) also found an effect of gender of the assessor in the evaluation of paraphilic disorders.

In terms of attitudes, our findings indicated that participants who endorsed the view that mental disorder diagnoses should only be applied to sexual arousal patterns and behaviour if they cause distress or impairment, significant risk of harm to the self or others, or lead to behaviour that violates the rights of others were more likely to index that the presence of a mental disorder should be considered in assigning criminal responsibility for frotteuristic and exhibitionistic acts. The perception of the likelihood of paraphilic disorders causing harm to self or others may be related to personal preconceived attitudes toward the disorders rather than on clinical training in this area. This may be particularly true for the frotteuristic disorder vignette, where older women clinicians may have considered this behaviour as a possible dangerous situation that should be more forcefully addressed. Although all vignettes depict a male subject, and men are generally perceived as more dangerous than women (Yoldi-Negrete et al., 2019), in Fuss et al.'s (2018) study men with frotteuristic behaviours were perceived as more dangerous than those with exhibitionistic behaviours. Frotteuristic behaviours involve direct physical contact with a non-consenting person and the risk of harm may have been considered higher by women clinicians, in comparison to exhibitionism, where physical contact is not involved.

For coercive sexual sadism and exhibitionistic disorder, differing attitudes about atypical sexual behaviours influenced clinicians' judgments about criminal responsibility. Clinicians' perception that any intense sexual interests other than genital stimulation or preparatory fondling with phenotypically normal, consenting human partners should be considered abnormal stigmatizes those individuals practicing diverse sexual behaviours even in the absence of an underlying paraphilic disorder (Cochran et al., 2014). Also, this represents an additional negative stigma toward people with paraphilic arousal patterns (Fuss et al., 2018; Waldura et al., 2016) that can be enacted in ways that are not criminal (e.g., through role-play or safe and consensual practice of "bondage and discipline") (Berner et al., 2003). A false positive paraphilic disorder diagnosis may represent a great liability to the individual, who may be perceived as more dangerous or more likely to re-offend (Martínez-López et al., 2019). In our analysis, it seems that personal conceptualizations and attitudes about sexual arousal patterns may influence implicit definitions of what is a mental disorder, which in turn may influence clinical decisions and forensic recommendations related to atypical sexual behaviours.

In the context of ICD-11 paraphilic disorders, of central relevance from WHO's perspective was distinguishing conditions that are appropriate targets of health services from those that are merely sexual preferences of no public health significance (Krueger et al., 2017). The commission of a sexual crime by a person with a paraphilic disorder does not exclude their need for treatment during their prison sentences or in forensic psychiatric treatment facilities. The correct identification of a paraphilic disorder in clinicians was the most important predictor of participants endorsing a need for treatment only in the frotteuristic disorder vignettes. Also, a positive attitude towards the acceptability of sexual patterns other than normative sexual behaviours may influence the perceived need for treatment in this vignette as well as in the coercive sexual sadism extreme vignette. Evidence from international research shows that the provision of adequate treatment for individuals who have committed sexual offenses with a paraphilic disorder helps prevent future sexual offenses (Marshall & Marshall, 2015).

The present study has limitations that should be acknowledged. First, the sample of clinicians should not be considered as representative of all clinicians worldwide. Another limitation is that vignettes only included male cases; paraphilic disorders are often perceived as disorders of men (Boysen et al., 2014) and available evidence suggests that clinicians' attitudes may operate differently for female cases (Fuss et al., 2018). Future studies should examine the impact of using vignettes focused on female, gender diverse, and non-heterosexual individuals. In addition, we want to highlight that global generalizations about the relationship between mental disorders and criminal responsibility are inherently limited because this varies according to what legal standard is used, based on the laws of the country in which each clinician practices. This should be considered in future studies.

In summary, the present study showed that the ICD-11 category of paraphilic disorders is useful for clinicians in differentiating non-pathological patterns of atypical sexual arousal from those that are considered mental disorders and have public health impact and are associated with dysfunction, distress, or harm to the individual or others (Reed et al., 2016). Also, our results show an interaction of the classification of paraphilic disorders, clinicians' gender, and attitudes with legal concepts associated with criminality, criminal liability if a diagnosis was indicated, and the need for treatment of these disorders in forensic settings. Increased formal education and clinical training about these disorders, as well as evidence-based treatment guidelines, are required to avoid biases that may come from preconceived ideas and personal attitudes. Women clinicians may be particularly sensitive to perceived threats of aggression and violence.

Atypical sexual arousal patterns and paraphilic disorders are subject to remarkably negative attitudes and stigmatization that also exists among clinicians. It would be important for clinicians to receive further training on sexual diversity and human rights as well as on ICD-11 diagnostic requirements to enhance their ability to provide evidence-based and socially competent diagnosis and care. Laws and policies that unnecessarily restrict the treatment of these patients in non-forensic settings—for example, when the individual is distress about their arousal pattern but no crime has been committed—should also be examined. The changes implemented in the classification of paraphilic disorders in the ICD-11 open the possibility of improving the diagnosis and treatment of these disorders in forensic settings and non-forensic clinical setttings as well as providing a more relevant framework for international public health surveillance and reporting.