Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Revista Española de Enfermedades Digestivas

versión impresa ISSN 1130-0108

Rev. esp. enferm. dig. vol.102 no.1 Madrid ene. 2010

Adult intussusception - 14 case reports and their outcomes

Intususcepción en el adulto. Revisión de 14 casos y su seguimiento

M. P. Guillén-Paredes, A. Campillo-Soto, J. G. Martín-Lorenzo, J. A. Torralba-Martínez, M. Mengual-Ballester, M. J. Cases-Baldó and J. L. Aguayo-Albasini

General Surgery Department. University General Hospital J. M. Morales Meseguer. Murcia, Spain. School of Medicine. Murcia, Spain

Article funded in part by FFIS (Foundation for Health Research and Training in the Region of Murcia, Spain, Group FFIS-008).

ABSTRACT

Aims: to analyze diagnostic and therapeutic options depending on the clinical symptoms, location, and lesions associated with intussusception, together with their follow-up and complications.

Patients and methods: patients admitted to the Morales Meseguer General University Hospital (Murcia) between January 1995 and January 2009, and diagnosed with intestinal invagination. Data related to demographic and clinical features, complementary explorations, presumptive diagnosis, treatment, follow-up, and complications were collected.

Results: there were 14 patients (7 males and 7 females; mean age: 41.9 years-range: 17-77) who presented with abdominal pain. The most reliable diagnostic technique was computed tomography (8 diagnoses from 10 CT scans). A preoperative diagnosis was established in 12 cases. Invaginations were ileocolic in 8 cases (the most common), enteric in 5, and colocolic in 2 (coexistence of 2 lesions in one patient). The etiology of these intussusceptions was idiopathic or secondary to a lesion acting as the lead point for invagination. Depending on the nature of this lead point, the cause of the enteric intussusceptions was benign in 3 cases and malignant in 2. Ileocolic invaginations were divided equally (4 benign and 4 malignant), and colocolic lesions were benign (2 cases). Conservative treatment was implemented for 4 patients and surgery for 10 (7 in emergency). Five right hemicolectomies, 3 small-bowel resections, 2 left hemicolectomies, and 1 ileocecal resection were performed. Surgical complications: 3 minor and 1 major (with malignant etiology and subsequent death). The lesion disappeared after 3 days to 6 weeks in patients with conservative management. Mean follow-up was 28.25 months (range: 5-72 months).

Conclusions: a suitable imaging technique, preferably CT, is important for the diagnosis of intussusception. Surgery is usually necessary but we favor conservative treatment in selected cases.

Key words: Intussusception. Adult intestinal invagination. Intestinal obstruction.

RESUMEN

Objetivos: analizar las opciones terapéuticas en función de la clínica, localización y lesión asociada a la intususcepción, así como, su seguimiento y complicaciones.

Pacientes y métodos: pacientes ingresados en el HGU Morales Meseguer (Murcia) desde enero de 1995 hasta enero 2009, con diagnóstico de invaginación intestinal. Se recogieron datos demográficos, clínicos, exploraciones complementarias, diagnóstico presuntivo, tratamiento, seguimiento y complicaciones.

Resultados: 14 pacientes (edad media 41,9 años, rango: 17-77), 7 varones y 7 mujeres, que debutaron principalmente con dolor abdominal. La exploración más fiable en el diagnóstico fue la tomografía computerizada, TC (8 diagnósticos, de 10 exploraciones). El diagnóstico preoperatorio se obtuvo en 12 casos, encontrando, invaginaciones ileocólicas en 8 casos (las más frecuentes), entéricas en 5 casos y colocólicas en 2, teniendo en cuenta que son 14 los pacientes y 15 las lesiones debido a la coexistencia de 2 invaginaciones en un mismo sujeto. La etiología de las intususcepciones es idiopática o secundaria a una lesión que hace de cabeza de invaginación. Según la naturaleza de dichas lesiones la causa de intususcepciones entéricas fue benigna en 3 casos y maligna en 2. De las ileocólicas, se repartieron equitativamente (4 benignas y 4 malignas); y de las colocólicas, sus lesiones fueron benignas (2 casos). Se realizó tratamiento conservador en 4 pacientes y quirúrgico en 10 (7 urgente). Con 5 hemicolectomías derechas, 3 resecciones de intestino delgado, 2 hemicolectomías izquierdas y una resección ileocecal. Las complicaciones quirúrgicas: 3 menores y 1 mayor (de etiología maligna y consecuente exitus). En los pacientes con manejo conservador desapareció la lesión entre 3 días y 6 semanas. Se siguieron durante 28,25 meses de media (rango 5-72 meses).

Conclusiones: para diagnosticar las intususcepciones es importante una adecuada técnica de imagen, recomendablemente TC. Abogamos por un tratamiento conservador en aquellos casos donde no se encuentre etiología de invaginación, según el tipo de intususcepción y clínica, siempre asociado a seguimiento.

Palabras clave: Intususcepción. Invaginación intestinal adulto. Obstrucción intestinal.

Introduction

Adult intestinal invagination represents less than 5% (1) of all intussusceptions, as it is typically a childhood condition. It is also the cause of bowel obstruction in just 1% of cases. For this reason it is important to remember that diagnosis is difficult; unlike its presentation in childhood the etiology of the lead point for invagination usually corresponds to a structural lesion, very often malignant in nature, this is why it is advisable to establish a syndromic and etiological diagnosis. The present study analyzes symptoms, complementary tests, and lesions, together with their management and subsequent follow-up, in patients over the 14-year history of our hospital.

Patients and methods

A retrospective descriptive study was conducted on all patients aged over 16 years who were diagnosed with intestinal invagination, both preoperatively and postoperatively, between January 1995 and January 2009 in any of the clinical departments at Morales Meseguer University Hospital (Murcia, Spain), a center serving a population of around 230,000 inhabitants. Fourteen patients with these characteristics were found from an analysis of 200,774 clinical records.

We reviewed demographic data (age, sex, service in which they were diagnosed, etc.) together with clinical signs, complementary tests, presumptive diagnosis, treatment applied, etiology and location of the head of the invagination, follow-up, and complications.

We decided to define the following types of invagination: a) enteric invagination, when the intussusception is located in the small bowel alone (jejuno-jejunal, jejuno-ileal and ileo-ileal); b) ileocolic invagination, if it includes the small bowel and large bowel at the same time; and c) colocolic invagination, involving just any part of the colon.

We also classed the etiology of the lesions composing the lead point for invagination as benign or malignant. The cases in which no causal lesion was found were included in the benign lesion group.

Results

-Demographic: over the 14 years' existence of our hospital 14 patients were identified with a preoperative and intraoperative diagnosis of intestinal invagination; they had a mean age of 41.9 years (range: 17-77) and were divided evenly between males and females (7 males and 7 females). Ten patients were diagnosed with symptoms of intussusception in the General and Digestive Surgery department, 3 in Hematology/Oncology, and 1 in the Digestive department. Five of these patients had previous abdominal surgery (2 appendectomies, 2 caesarean sections, and 1 low anterior resection for rectal cancer four years earlier, with normal follow-ups), and one required a hematopoietic progenitor allotransplant for acute myeloid leukemia (M5), with normal follow-ups, six years prior to the diagnosis with intussusception.

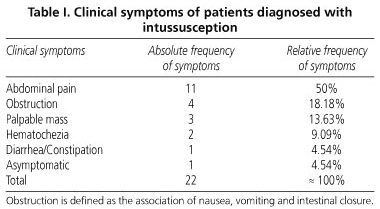

-Symptoms: the dominant symptom (Table I) was abdominal pain (11 cases), followed by obstructive syndrome (4), defined as the association of nausea, vomiting, and intestinal closure. A palpable abdominal mass was found in 3 cases, hematochezia in 2 patients, and absence of symptoms and association of diarrhea/constipation in 1 patient who was subsequently diagnosed with Crohn's disease.

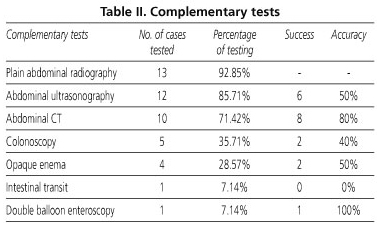

-Diagnostic studies: a correct preoperative diagnosis of intestinal invagination (Table II) was established in 12 of the cases, for which a series of complementary tests was required: most of the patients received an abdominal radiography (n = 13), 12 had ultrasonography, 10 a computed tomography, 5 a preoperative colonoscopy, 4 an opaque enema, and 1 an intestinal transit together with double-balloon enteroscopy.

However, the tests that yielded diagnostic accuracy in order of frequency were: CT (8 from 10 cases were diagnosed correctly), abdominal ultrasonography (6 preoperative diagnoses of the 12 who received it), opaque enema (2 diagnoses of the 4 tests performed), colonoscopy (2 diagnoses from 5 tests), double balloon enteroscopy (a single case and a single correct diagnosis), and intestinal transit (with no diagnosis). There were only two patients in whom diagnosis was established intraoperatively: one of them started with symptoms of diffuse peritonitis, and the other revealed a lead point of tumor origin infiltrating the underlying tissue. The most accurate complementary test for preoperative diagnosis for most patients was abdominal CT.

-Etiology and locations: in the 14 patients studied we found 15 intestinal invaginations. The most common locations (Table III) were ileocolic (8 cases), followed by enteric (5 cases) and colocolic (2 cases). The types of intussusception were classed in turn according to their benign or malignant etiology at the lead point. Enteric invaginations were benign in 3 of the cases and malignant in 2. The nature of the lesion in the ileocolic invaginations was divided equally between benign and malignant (4 cases of each). Lastly, colocolic lesions, the least common in our series, were all benign.

-Treatment and complications: ten of the 14 patients underwent surgery, and 4 had conservative treatment plus follow-up. Seven of the operated upon patients required emergency surgery for signs of ischemia or sepsis, whereas the rest were able to receive elective surgery. The type of operation varied according to location, lesion size, cause of lead point for invagination, and bowel viability. Thus we performed 5 right hemicolectomies with resection of the invaginated ileum, 3 small bowel resections, 2 left hemicolectomies, and 1 ileocaecal resection. In the four patients diagnosed radiologically who did not undergo surgery half of the invaginations were enteric and resolved spontaneously, as shown by subsequent ultrasonography or CT follow-ups (at 2 and 3 weeks); furthermore, both were a casual finding (one during complementary tests for a recently diagnosed Crohn's disease, and one during the study of a different non-digestive abdominal pathology). The two remaining unoperated cases presented with ileocolic intussusception, the etiology of which was in one case secondary to pancolitis in a patient undergoing transplantation for AML-M5, and in the other due to nodular lymphoid hyperplasia confirmed by biopsy (Table IV).

The four unoperated patients were followed up for a mean of 28-25 months (range: 5-72 months) with radiological controls, which revealed the disappearance of the lesion at 3 days and 3, 4 and 6 weeks respectively, with a complete absence of symptoms.

As regards the complications or sequel of surgery, it is worth noting just three cases of minor morbidity (seroma, phlebitis, and eventration), and a major complication conditioned by the etiology of a lead point: an adenocarcinoma with both local and distant recurrence resulting in the patient's death 30 months after surgery.

Discussion

Intestinal invaginations are a complex disorder with multiple therapeutic options that have not been standardized due to the impossibility of collecting a sufficient number of study patients. The present review aims to show our hospital's 14-year experience with this condition: clinical symptoms, safer complementary tests, treatments, and especially follow-up of patients.

Unlike with children the etiology in adults is verified in 70-90% of cases (2), and intussusceptions of the small bowel are most common.

The mean age at presentation in our study was 41.9 years (range: 17-77), which is very similar to other series (3,4) with an equal distribution by sex. However, we observed a substantial difference to other studies, which lies in the nature of lesions. It is true that there is a greater predominance of enteric vs. colonic invaginations (75-80%) (5) as in the literature, but ours is distinguished by the nature of lesions, which we know to be varied. In the small bowel they are characterized as benign lesions such as hamartomas, lipomas, leiomyomas, inflammatory adenomas, Meckel's diverticulums, adhesions, etc., and to a lesser extent malignant tumors such as metastases (6). In the colon the possibility of malignancy is greater (5,7,8) (usually adenocarcinomas). However, in our 14-year experience we have not witnessed a single colocolic invagination due to a malignant tumor; in fact, considering them together with ileocolic invaginations, the rate of benign lesions far exceeds that of malignant lesions (60 versus 40%), which raises the question of whether the recent introduction of screening for colorectal cancer (since 2005 in our area) makes early detection possible and prevents the anatomical and pathological conditions leading to intussusception: a certain size, fixedness allowing telescoping of the proximal segment into the distal intestine, etc.

The clinical presentation of invaginations is diverse: in our series, as in others (9,10), the most common symptom was abdominal pain, followed by obstruction and a palpable mass (symptoms and signs that may appear in multiple abdominal disorders), which makes diagnosis difficult and at times leads to no more than 30.7% of patients having a preoperative diagnosis (4). Nevertheless, the fact that 12 of our 14 cases were preoperatively diagnosed suggests the use of an adequate imaging technique; despite ultrasonography being the most frequently used technique it did not guarantee a diagnosis on most occasions, which is why subsequent abdominal CT (11) was recommended, which did reveal the intussusception and its location. However, the etiology is difficult to determine in a preoperative study, since edema or hemorrhagic intussusception may simulate a mass at this level (12), which is why the etiological diagnosis will be established either with other biopsy-related tests or during pathological examination after sampling.

Many reviews support invagination as an indication for surgery in adults due to the risk of intestinal ischemia and possible malignancy of the lead point of invagination. However, we consider it important to take associated symptoms into account and on the basis of these conduct more accurate diagnostic studies to rule out a tumor origin if not done previously; moreover, the diameter and length of the invagination, together with the presence or absence of an associated lesion, and the type of invagination are predictors of spontaneous resolution (13,14).

The present review highlights the analysis of patients in whom conservative management was chosen due to the absence of clinical manifestations and of a demonstrable lesion as lead point of invagination. They had a regular follow-up with radiological controls (abdominal ultrasonography/CT), which revealed not only the spontaneous resolution of symptoms (at 3 days and 3, 4 and 6 weeks) but also the absence of a new invagination over time (mean follow-up of 28.25 months). This suggests the possibility of spontaneous invaginations with a still unknown incidence and a conservative treatment as yet not promulgated by many surgeons (15).

Many reviews consider a reduction prior to resection, which we rule out with any type of invagination due to a possible mobilization of a non-benign lesion and our doubts as to bowel viability if it required surgery for associated symptoms.

We conclude that invaginations are a disorder to bear in mind when primarily diagnosing an acute abdomen, and that in selected cases we favor a new treatment depending on intussusception location and the radiological presence of an associated lesion. This is shown by our series of patients diagnosed with enteric invagination but with no signs of lesions, who were treated conservatively and showed a satisfactory resolution of symptoms only a few days after diagnosis.

References

1. Haas EM, Etter EL, Ellis S, Taylor TV. Adult intussusception. Am J Surg 2003; 186: 75-6. [ Links ]

2. Gordon RS, O'Dell KB, Namon AJ, Becker LB. Intussusception in the adult-a rare disease. J Emerg Med 1991; 9: 337-42. [ Links ]

3. Barussaud M, Regenet N, Briennon X, de Kerviler B, Pessaux P, Kohneh-Sharhi N, et al. Clinical spectrum and surgical approach of adult intussusceptions: a multicentric study. Int J Colorectal Dis 2006; 21(8): 834-9. [ Links ]

4. Erkan N, Haciyanli M, Yildirim M, Sayhan H, Vardar E, Polat AF, et al. Intussusception in adults: an unusual and challenging condition for surgeons. Int J Colorectal Dis 2005; 20(5): 452-6. [ Links ]

5. Azar T, Berger DL. Adult intussusception. Ann Surg 1997; 226: 134-8. [ Links ]

6. Martín JG, Aguayo JL, Aguilar J, Torralba JA, Liron R, Miguel J, et al. Invaginación intestinal en el adulto. Presentación de siete casos con énfasis en el diagnóstico preoperatorio. Cirugía Española 2004; 70: 93-7. [ Links ]

7. Pollack CV, Pender ES. Unusual cases of intussusception. J Emerg Med 1991; 9: 347-55. [ Links ]

8. Jiménez-Rodríguez RM, Serrano-Borrero I, Díaz-Pavón JM, Socas-Macías M, Vázquez-Monchul JM. Subacute intestinal obstruction secondary to colonic lipoma intussusception. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2008; 100(3): 182-3. [ Links ]

9. Zubaidi A, Al-Saif F, Silverman R. Adult intussusception: a retrospective review. Dis Colon Rectum 2006; 49(10): 1546-51. [ Links ]

10. Wang LT, Wu CC, Yu JC, Hsiao CW, Hsu CC, Jao SW. Clinical entity and treatment strategies for adult intussusceptions: 20 years' experience. Dis Colon Rectum 2007; 50(11): 1941-9. [ Links ]

11. Casamayor Franco MC, Yánez Benítez C, Hernando Almudí E, Ligorred Padilla LA, García Omedes A, López López JI, et al. Adult intussusception. CT diagnosis. Rev Esp Enferm Dig 2007; 99(12): 722. [ Links ]

12. Huang BY, Warshauer DM. Adult intussusception: diagnosis and clinical relevance. Radiol Clin North Am 2003; 41(6): 1137-51. [ Links ]

13. Rea JD, Lockhart ME, Yarbrough DE, Leeth RR, Bledsoe SE, Clements RH. Approach to management of intussusception in adults: a new paradigm in the computed tomography era. Am Surg 2007; 73(11): 1098-105. [ Links ]

14. Omori H, Asahi H, Inoue Y, Irinoda T, Takahashi M, Saito K. Intussusception in adults: a 21-year experience in the university-affiliated emergency center and indication for nonoperative reduction. Dig Surg 2003; 20(5): 433-9. [ Links ]

15. Lebeau R, Koffi E, Diané B, Amani A, Kouassi JC. Acute intestinal intussusceptions in adults: analysis of 20 cases. Ann Chir 2006; 131(8): 447-50. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

María Pilar Guillén-Paredes.

Plaza Preciosa, 5, 8º A.

30008, Murcia, Spain.

e-mail: mapimed@hotmail.com

Received: 08-06-09.

Accepted: 13-10-09.

texto en

texto en