Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Archivos de Zootecnia

versión On-line ISSN 1885-4494versión impresa ISSN 0004-0592

Arch. zootec. vol.60 no.230 Córdoba jun. 2011

https://dx.doi.org/10.4321/S0004-05922011000200001

Transport of cattle in Spain. Technical, administrative and welfare aspects according to the destination

Transporte de terneros en España. Aspectos técnicos, administrativos y de bienestar según el destino

Averós, X.1*, Riu, M.1, López, J.2, Herranz, A.3, Ribó, O.4 and Gosálvez, L.F.1

1Departament de Producció Animal. Universitat de Lleida. Av. Rovira Roure, 191. 25198 Lleida. España.*Current address: UMR SENAH, INRA. Domaine de la Prise. 35590 Saint Gilles. France.

2Asociación Española de Productores de Vacuno de Carne (ASOPROVAC). Av. de Burgos 20-B. 28108 Alcobendas. Madrid. España.

3Asociación Nacional de Transportista de Ganado (ANTA). Santísima Trinidad, 30, 1o1a. 28010 Madrid. España.

4Animal Health and Welfare (AHAW). European Food Safety Authority. Largo N. Palli 5/A. I-43100 Parma.

Supported by funding from the Spanish Agriculture Ministry (CO-557), and European Social Fund by means of a DIUE grant (2008FIC 00187 grant). The authors also thank the collaboration of Mrs M.J. Lueso and to ANPS, ANPROGAPOR, ANCOPORC, ASOCARNE, Fund. P. Prog. Prod. Anim. and all the companies that gave support.

SUMMARY

To obtain a thorough description of how are cattle transported in spain with respect to the journey destination a survey was performed in 2004 and 2005. Information was obtained by means of a 119-parameters questionnaire, and 44 transport operators representative of the sector (27 slaughterhouses, 10 traders, and 7 cattle markets) were interviewed. Over 80% of journeys transported growing-finishing/finished animals, and about 3% of journeys transported both growing-finishing/finished and reproductive animals. With respect to farm transports, slaughter transports loaded in fewer farms (1.2 vs. 1.4 farms; p<0.05) and in most cases animals were not fasted (92.9 vs. 24.3%; p<0.001). slaughter transports were short, 125 km and 2.5 h on average, with farm transport duration being double (p<0.001), although 21% of slaughter transports lasted more than 8 hours, and 1.7% lasted more than 29 hours. Farm journeys transported more animals and stocking densities were higher (p<0.001), although most of drivers affirmed that it was possible to transport more animals in a suitably manner. Only 2.3% of slaughter transports were carried out using 2 drivers, and 80% of slaughter transports made no stops, substantially differing with what was observed in farm transports (p<0.001). The driver participated in the loading and unloading of animals, normally assisted by another person except for the unloading at slaughterhouses (40%). Average loading and unloading times in farm transports were about 60 and 30 minutes respectively, double than slaughter transports (p<0.001), although average loading and unloading time/animal were slightly higher in slaughter transports (3.1 and 1.4 minutes/animal respectively). Transport showed a limited effect on physical integrity of cattle, although a trend towards higher number of deaths and lesions was observed in slaughter transports. Transports were mainly carried out by specialized hauliers under request (60%), with vehicle being owned by the trader in 30.5% of farm transports, and by the farmer in 27% of slaughter transports (p<0.001). Drivers had an average experience of 17 years. Independently form destination; transport companies did not make research activities, with few of them performing training courses (8%). The compliance with a quality scheme was mainly declared by hauliers bound to a slaughterhouse, while load insurance was mainly contracted by traders. A high percentage of drivers declared to know animal welfare legislation, which this is not totally obeyed, and that laws should be closer to real circumstances. Almost half of slaughter transport drivers showed no interest in proposing improvements in current legislation, with proposals mainly being the need to being more informed and a better knowledge on the basis of the transport stops aspect.

Key words: Mortality. Lesions. Slaughter.

RESUMEN

Para conocer en detalle como se transporta el ganado vacuno en España según el destino del viaje, entre los años 2004 y 2005 se entrevistaron 44 operadores representativos del sector (27 mataderos, 10 comerciantes y 7 mercados) mediante cuestionarios que recogían información relativa a 119 parámetros. Más del 80% de los viajes fueron de animales cebados/para cebo, y algo más de un 3% de los viajes transportaban animales cebados/para cebo y reproductores. Los transportes a matadero cargaron en un menor número de explotaciones (1,2 vs. 1,4 granjas; p<0,05) respecto aquellos destinados a granja, en la mayoría de los casos animales no ayunados (93 vs. 24,3%; p<0,001). Los viajes a matadero fueron cortos, 125 km, y 2,5 horas de media, parámetros que se duplicaron en los viajes de bovinos para vida (p<0,001), aunque el 21% de los viajes para sacrificio fueron de más de 8 horas, y un 1,7% de más de 29 horas. Los viajes para vida se cargaron a mayores densidades (p<0,001) y transportaron más animales, aunque los chóferes opinaron que su camión podía transportar un mayor número de animales en buenas condiciones. El 80% de los viajes a matadero no efectuaron paradas y sólo un 2,3% fueron realizados por 2 chóferes, parámetros opuestos a los de los viajes para vida (p<0,001). El camionero intervino en la carga y en la descarga, normalmente con la ayuda de otra persona excepto en la descarga en el matadero (40%). El tiempo medio de carga y descarga en viajes a granja fue de unos 60 y 30 minutos respectivamente, el doble que en viajes a matadero (p<0,001), aunque el tiempo unitario de carga y descarga fue algo mayor en viajes a matadero (3,1 y 1,4 minutos/ animal respectivamente). El viaje mostró un efecto limitado sobre la integridad física de los animales, aunque se detectó una tendencia hacia valores superiores de mortalidad y lesiones en los viajes a matadero. Los viajes fueron realizados principalmente por transportistas especializados y en régimen discrecional (60%), siendo el vehículo propiedad del comerciante en el 30,5% de los viajes con destino a granja o del ganadero en el 27% de los viajes a matadero (p<0,001). Los chóferes afirmaron tener una experiencia media de 17 años. Independientemente del destino las empresas no realizan actividades de experimentación, y muy pocas de formación (8%). Los transportistas vinculados a matadero fueron los que principalmente declararon que su empresa seguía algún programa de calidad, mientras que el seguro de carga era principalmente contratado por los comerciantes. Un elevado porcentaje de chóferes declaró conocer la legislación en bienestar animal, que no se cumple totalmente, y que en su opinión se debería aproximar más a las circunstancias reales. La mitad de los chóferes a matadero no mostró interés en proponer mejoras en la actual legislación, y aquellos que las propusieron pidieron mayoritariamente más información y que se estudie mejor el fundamento del régimen de paradas obligatorias.

Palabras clave: Mortalidad. Lesiones. Sacrificio.

Introduction

Spanish cattle census is approximately 900 thousand dairy cows and 2 million beef cows (MAPA, 2008a), with 600-800 thousand calves being imported annually to growing-finishing farms (MINHAC, 2008). This implies the need to transport 2,2 million grown-finished calves, and 400 thousand cull cattle to slaughter every year (MAPA, 2008b), reflecting the importance of transport in livestock production. Current transport necessities involve the existence of material resources and specific working protocols depending on the typology of transported animals, as well as the creation of a number of specialized companies.

Twentieth century western society has promoted the creation of different laws concerning the protection of animals, so that in the European Union (EU) transport is controlled by means of a common Regulation for all of the Member states (Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2005, 2005). Factors associated with a negative effect of transport on the welfare of cattle and their meat quality have been thoroughly reviewed by different authors (Tarrant, 1990; Warriss, 1990; Knowles, 1995, 1999), with climatic conditions (Malena et al., 2006; Averós et al., 2008a); journey duration (Kent and Ewbank, 1983, 1986a,b; Knowles et al., 1999a,b) and other technical aspects (Mitchell and Kettlewell, 2008), being particularly important. Nevertheless, much of literature related to animal welfare during transport (EFSA, 2004; Ribó et al., 2008) was obtained by means of studies carried out under experimental conditions, in many cases using protocols greatly differing from usual commercial procedures. It may be therefore assumed that, in general, the scientifical basis of the analysis of the influence of the journey on the welfare of animals is still scarce (Gosálvez, 2004, 2006).

On the other hand, and with the exception of reports related to movement statistics, very few references describing usual cattle transport procedures exist (Villarroel et al., 2001; Ljungberg et al., 2007). In order to base political decisions, a gap of knowledge exists with respect to how commercial operators work, gap which can't be close by means of purely empirical studies.

Therefore, the aim of this study is to offer a general description of cattle transport main parameters under spanish commercial conditions depending on the journey destination, information that would be extremely useful as a link between scientific literature and animal transport regulation needs.

Material and Methods

Information regarding 415 cattle journeys to farm or slaughter was obtained, being transported around 20 000 animals. Information was collected directly from spanish operators, in 27 slaughterhouses, 7 cattle markets, and 10 cattle traders. Operators were chosen after some meetings with Professional Associations and spanish Administration Representatives, aiming to describe as accurately as possible spanish cattle logistics. Information on transports originating in farms of 35, and finishing farms of 38 spanish provinces was obtained.

Between 2004 and 2005 transport operators were visited as many times as necessary in order to obtain detailed description of their activity. For this reason the number of journeys per operator, randomly chosen from among all available, was also the minimum necessary. When possible, the monitored journeys were those in which the interviewer could directly observe the unloading of the animals.

Each transport was monitored by means of a questionnaire collecting information about 119 different aspects related to the transported animals, the loading and unloading procedures, the journey, the means of transport, the driver, the companies involved, and some economic and administrative aspects. As shown in table I, the studied transports involved the 4 seasons, with all environmental situations being represented. The number of deaths and injuries, and the typology of lesions at the end of the journey, was recorded for each transport.

To determine the characteristics of transports depending on their destination (farm vs. slaughterhouse) data were statistically analyzed using SAS software (SAS Institute Inc., 2006). Discrete dependent variables were transformed into binary response variables, and the effect of the type of transport on the weighted least square estimates of these variables was studied by means of χ2 tests using the CATMOD procedure. The effect of the type of transport on continuous dependent variables was tested by means of F-tests using the GLM procedure. In case of a significant (p<0.05) effect LS means were statistically separated using t-tests.

Results and Discussion

Table II shows the typology of transported cattle depending on their destination. As expected, the average weight of slaughter animals was significantly higher than that of cattle transported to farms (p<0.001), although no differences were found in the percentage distribution of journeys depending on the typology of animals.

Most of farm journeys transported calves up to 325 kg, with the main percentage being animals among 201 and 325 kg (27.7%), and with percentage values significantly higher than those of slaughter transports with the same weight rank. On the other hand, most of slaughter journeys transported animals among 326 and 550 kg, percentage rank being significantly higher than that of farms animals (p<0.001). Percentage of slaughter journeys transporting animals >550 kg was significantly higher than the percentage of animals with a similar weight transported to farm (p<0.01).

Farm journeys generally transported a higher number of animals than slaughter journeys, except for the case of cattle > 550 kg, transporting 12-16 animals in both cases. A slaughter journey transporting only 1 calf classifiable as <200 kg was detected, being representative of a minor beef consumption model. Similarly, farm journeys transported animals at higher stocking densities (p<0.001), except for the case of heavier cattle.

Table III shows different aspects related to the loading, the journey, and the unloading depending on the destination of animals. Drivers mainly affirmed that lorries could transport more animals under suitable conditions, specially in farm journeys (p<0.05). Transports were generally short, although farm transports' average distance and duration (124.3 km and 2.4 hours respectively) were significantly lower than those of slaughter transports (p<0.001). Nevertheless, slaughter transports were carried out at a lower average speed than farm transports (p<0.01) because slaughter transports travelled around a higher percentage of local roads (p<0.001) and a lower percentage of motorways (p<0.01). It is remarkable that the percentage of >8 hour slaughter transports (defined as long distance transports according to the European Regulation on the protection of animals during transport (Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2005, 2005)) was low, and significantly lower than the farm transports' corresponding percentage (p<0.001), indicating that spanish cattle slaughterhouses provision, when possible, from nearby farms due to cost reduction aspects. On the contrary, the number of journeys lasting >29 hour was low. In this cases transports are bound by the European Regulation to make a 24 hour stop and to unload animals. Although from the point of view of cattle welfare it is recommended to make 24 hour stops if they are necessary (Knowles et al., 1999b), it is still not clear if they benefit animals from the sanitary point of view, additionally complicating the journey logistics.

The number of loading points was fewer in the case of slaughter transports (table III ; p<0.05), mainly being growing-finishing farms. On the other hand, the percentage of loads performed at assembly centres and cattle markets was higher for farm transports than for slaughter transports (p<0.001), accounting for 44.4% of the total of loads. This percentage may nonetheless be subject to a strong variability due to an adaptation to the structural changes occurring in the sector, with a reduction in the importance of markets in cattle trade. Fasting animals prior to transport was not a common practice, particularly in slaughter transports (7.1%; p<0.001), and in case of doing so the average fasting time was around 8 hours.

For both destinations, in more than 99% of cases the driver participated in the loading, almost always being assisted by another person. Slaughter journeys lorries were loaded faster than farm journeys (p<0.01), although the individual duration did not show differences among destinations. similarly, drivers also participated in most of the unloadings, although the assistance of other persons at slaughterhouses was significantly lower than at farms (p<0.001). Furthermore, the unloading total duration at slaughterhouses was significantly lower than in farms although individual duration neither showed significant differences among destinations.

As expected due to transports' duration, neither changes in lorry's tractor nor transhipment of animals were observed. Additionally, and independently from destination, most of transports were carried out by only 1 driver, what might be explained by the fact that the studied transports were performed only in spanish territory, so that durations were relatively short and therefore the participation of 2 drivers was unnecessary. The duration of transports would also be related to the low number of stops made, particularly in slaughter transports (p<0.001), and with the number of transports with more than one stop being higher in the case of farm transports (p<0.001). The percentage of transports encountering traffic problems was low, and did not show significant differences due to the destination, what might be explained by the adaptation of drivers to the different transport conditions.

Table IV shows the effect of transport on animal's mortality and physical integrity, being remarkable the small number of incidents found. Independently from the destination, mortality at the end of transport was 0.6%, being higher than values found in other regions (Malena et al., 2006) and other species (Gosalvez et al., 2006; Averós et al., 2008b). Percentage of injured animals during transport was 2.7%, with lesions being lameness, leg injuries, and unspecific wounds. It is apparent the fact that the number of lesions observed at the end of slaughter transports was higher, and no mortality was observed, with respect to farm transports. This might be explained by the fact that slaughter journeys were shorter, and transported older and heavier animals.

Some administrative parameters depending on the journey's destination are shown in table V. For both destinations, in more than 90% of journeys the driver affirmed to be the responsible for cattle, followed by the animals' owner (4.5% on average). In more than 97% of journeys animals' condition was controlled before the loading, although slaughter transports' drivers affirmed to have a higher control of their work by means of quality guarantee systems (p<0.05), what might be due to the fact that an important number of slaughter transports are carried out using lorries owned by the slaughterhouse, many of which have process quality control programs established. This influence of the operating company also appeared in those aspects related to the journey plan, with a higher percentage of affirmative answers in slaughter transports for both questions (p<0.05), while live animal traders showed a higher trend to insure their activity and their load (p<0.05).

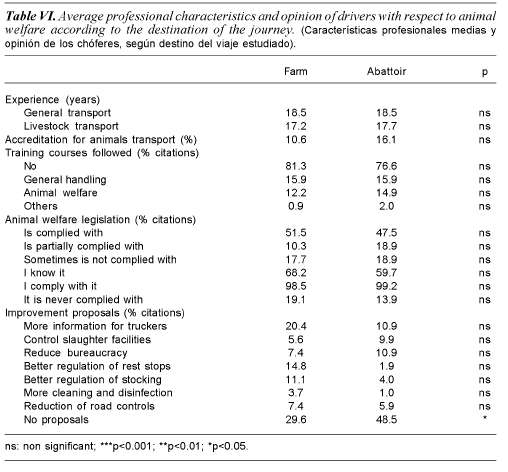

The average professional profile and the opinion of drivers about those aspects related to animal welfare with respect to the destination are shown in table VI. Drivers declared an average driving experience of 17 years, having specialized in transport of animals after 1 or 2 years of driving lorries. This specialization was nevertheless unofficial, since less than 17% of interviewees declared to have an official accreditation to transport livestock or having attended a training course. Less than 25% of drivers declared having attended a livestock course, with less than 10% of drivers having attended more than one course. Courses were mainly dedicated to animal handling and animal welfare, being slightly higher than 12% although an increase in this percentage is hopefully expected due to the transport Regulation in force (Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2005, 2005), with all persons involved in animal transport being bound to follow an animal welfare course. The subjective assessment of drivers with respect to the current European legislation on animal welfare showed some interesting results. No differences appeared with respect to the destination, with an average of 64% of drivers affirming to have knowledge of legislation, although only 49.5% of them believed that legislation was complied with. This might be due to hauliers not being sure of knowing all the legislation aspects, since they also believed that Regulation is very extensive.

The average percentual assessment of drivers' proposals to improve the welfare of transported cattle is also shown in table VI. A lack of interest in proposing any improvement was observed, what might be due to some pessimism with respect to the future of the activity, mood particularly accentuated in the case of slaughter transport drivers (48.5% vs. 29.6%; p<0.05). Among all proposals it was remarkable the need for additional information (more than 25% of citations) while almost 14% of interviewees called for additional in-depth studies on the suitability of current rest stops, these percentage being higher than those of other aspects such as stocking density. surprisingly, the reduction of official bureaucracy and of the different controls did not appear to be a priority for hauliers.

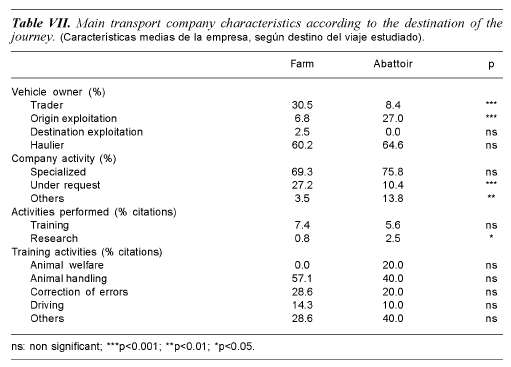

Characteristics related to the transport company are shown in table VII. In more than 60% of cases the vehicle was owned by specialized hauliers working under request. Traders did not use to be the owner of the vehicle, although the percentage was significantly higher in farm transports with respect to slaughter transports (30.5 vs. 8.4%; p<0.001). Hauliers did not show an interest in research, with only 2.5% of slaughter transport drivers affirming that their company carried out this activity, with this percentage being triple than in farm transport companies (p<0.05). This might be due to the fact that some slaughterhouses conduct some research although it may not be directly related to the welfare of animals. A reduced interest in training activities was also observed, being less than 8% of the total interviewed transports, and with no significant differences between destinations. Most of training activities performed by transport companies were related to the handling of animals (60%), with slaughterhouses showing an interest in taking care of their image since some of them forced their suppliers to follow animal welfare training courses.

Conclusion

This study provides an accurate description of how cattle commercial transports are performed in spain. Slaughter transports are generally shorter than farm transports, with only 21% being >8 hours, and therefore falling into the long transport definition according to the European Regulation. Farm journeys transported a higher number of animals and at higher stocking densities, being faster due to a higher proportion of journey being carried out in motorways. The percentage of mortality and injured animals was low in comparison with values found in other species. Transports were mainly effectuated by specialized hauliers under request, and around 30% of journeys were performed by lorries owned by traders and farmers, in farm and slaughter transports respectively. Drivers were sceptical with respect to the future of their activity, and their improvement proposals were related to the revision of the rest stops during journeys, and the need for more information.

Bibliography

Averós, X., Martín, S., Riu, M., Serratosa, J. and Gosálvez, L.F. 2008a. Stress response of extensively reared young bulls being transported to growing-finishing farms under spanish summer commercial conditions. Livest. Sci., 119: 174-182. [ Links ]

Averós, X., Knowles, T.G., Brown, S.N., Warriss, P.D. and Gosálvez, L.F. 2008b. Factors affecting the mortality of pigs during transport to slaughter. Vet. Rec., 163: 386-390. [ Links ]

Council Regulation (EC) No 1/2005. 2005. On the protection of animals during transport and related operations and amending Directives 64/432/ EEC and 93/119/EC and Regulation (EC) No 1255/97. Off. J. L 3: 0001-0044. [ Links ]

EFSA. 2004. European Food safety Authority. scientific opinion of the scientific Panel on Animal Health and Welfare on a request from the Commission related to the welfare of animals during transport. Question No EFSA-Q-2003-094. Adopted on 30th March 2004. (www.efsa. europa.eu/en/science/ahaw/ahaw_opinions/424.html (1-03-09). [ Links ]

Gosálvez, L.F. 2004. La protection des animaux en cours de transport. Public hearing, agriculture and rural development. European Commission. Brussels. Belgium. 21 of january. [ Links ]

Gosálvez, L.F. 2006. Public hearing related to the Comunity Action Plan for the Protection and Welfare of Animals (2006-2010). Agriculture and rural development. European Commission. Brussels. Belgium. 20 of may. [ Links ]

Gosálvez, L.F., Averós, X., Valdelvira, J.J. and Herranz, A. 2006. Influence of season, distance and mixed loads on the physical and carcass integrity of pigs transported to slaughter. Meat Sci., 73: 553-558. [ Links ]

Kent, J.E. and Ewbank, R. 1983. The effect of road transportation on the blood constituents and behaviour of calves. I. six months old. Br. Vet. J., 139: 228-235. [ Links ]

Kent, J.E. and Ewbank, R. 1986a. The effect of road transportation on the blood constituents and behaviour of calves. II. One to three weeks old. Br. Vet. J., 142: 131-140. [ Links ]

Kent, J.E. and Ewbank, R. 1986b. The effect of road transportation on the blood constituents and behaviour of calves. III. Three months old. Br. Vet. J., 142: 326-335. [ Links ]

Knowles, T.G. 1995. A review of post transport mortality among younger calves. Vet. Rec., 137: 406-407. [ Links ]

Knowles, T.G. 1999. A review of the road transport of cattle. Vet. Rec., 144: 197-201. [ Links ]

Knowles, T.G., Brown, S.N., Edwards, J.E., Phillips, A.J. and Warriss, P.D. 1999a. Effect on young calves of a one-hour feeding stop during a 19hour road journey. Vet. Rec., 144: 687-692. [ Links ]

Knowles, T.G., Warriss, P.D., Brown, S.N. and Edwards, J.E. 1999b. Effect on cattle of transportation by road for up to 31 hours. Vet. Rec., 145: 575-582. [ Links ]

Ljungberg, D., Gebresenbet, G. and Aradom, S. 2007. Logistics chain of animal transport and abattoir operations. Biosys. Eng., 96: 267-277. [ Links ]

Malena, M., Voslarova, E., Tomanova, P., Lepkova, R., Bedanova, I. and Vecerek, V. 2006. Influence of travel distance and the season upon transport-induced mortality in fattened cattle. Acta Vet. Brno., 75: 619-624. [ Links ]

MAPA. 2008a. Encuesta ganadera. http://www.mapa.es/es/estadistica/pags/encuestaganadera/encuesta.htm (26/05/08). [ Links ]

MAPA. 2008b. Encuesta de sacrificio de ganado. http://www.mapa.es/es/estadistica/pags/sacrificio/encuesta.htm (26/05/08). [ Links ]

Mitchell, M.A. and Kettlewell, P.J. 2008. Engineering and design of vehicles for long distance road transport of livestock (ruminants, pigs and poultry). Vet. Ital., 44: 2001-213. [ Links ]

MINHAC. 2008. Estadísticas de Aduanas. http://www.agenciatributaria.es/aeat/aeat.jsp?pg=aduanas/es_Es (05/06/08). [ Links ]

Ribó, O., Candiani, D., Aiassa, E., Correia, S., Afonso, A., Massis, F. and Serratosa, J. 2008. Using scientific evidence to inform public policy on the long distance transportation of animals: role of the European Food safety Authority (EFSA). Vet. Ital., 44: 87-94. [ Links ]

SAS Institute, Inc. 2006. Base SAS® 9.1.3 Procedures Guide. second Edition. Volumes 1, 2, 3, and 4. SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC. USA. [ Links ]

Tarrant, P.V. 1990. Transport of cattle by road. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci., 28:153-170. [ Links ]

Villarroel, M., María, G.A., Sierra, I., Sañudo, C., García-Belenguer, S. and Gebresenbet, G. 2001. Critical points in the transport of cattle to slaughter in Spain that may compromise the animals' welfare. Vet. Rec., 149: 173-176. [ Links ]

Warriss, P.D. 1990. The handling of cattle pre-slaughter and its effects on carcass and meat quality. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci., 28: 171-186. [ Links ]

Recibido: 30-06-08.

Aceptado: 4-2-09.