Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Dynamis

versión On-line ISSN 2340-7948versión impresa ISSN 0211-9536

Dynamis vol.30 Granada 2010

Popularising right food and feeding practices in Spain (1847-1950). The handbooks of domestic economy

Enrique Perdiguero-Gil and Ramón Castejón-Bolea (*)

(*) History of Science. Miguel Hernández University. quique@umh.es

This research was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science Project "Alimentación y sociedad: prácticas y discursos en la primera mitad del siglo XX" (HUM2005-04961-C03-C03).

ABSTRACT

The aim of this paper is to analyze a sample of domestic economy handbooks in order to assess the popularization of correct food and feeding practices in Spain between 1847 and 1950. With this contribution, we wish to evaluate another factor that would influence the Spanish food transition. We are aware that this is a very indirect source, given the high levels of illiteracy among women in Spain during the last third of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. A further factor to be considered is the low proportion of girls attending school. We have analyzed the handbooks published in three periods. The first ranges from the last third of the 19th century to the first decade of the 20th. These handbooks are considered in order to provide background for a comparison with the works published from 1900 onwards. The second period focuses on the 1920s and the 1930s. The last period covers the handbooks published after the Civil War under the monopoly of the Sección Femenina (women's section of the Falange). Over the years under consideration, recommendations underwent a progressive modification from the very simple leaflets used in the 19th century to the introduction of scientific factors into the teaching of domestic economy. The work of Rosa Sensat represented the beginnings of this trend. A further modernizing factor was the appearance of vitamins in some of the handbooks. After the war, the number of handbooks decreased and they were, in general, very poor. If we consider the content on vitamins, there was a lack or shortage of information in comparison with some of the books published in the same period outside the monopoly of the Sección Femenina. In conclusion, we can state that the repetition of recommendations on good feeding habits and the increase in girls attending school would exert a positive influence on the food transition of the Spanish population.

Key words: Education, girls, food, Spain, first half of the 20th century.

Palabras clave: Educación, niñas, alimentación, España, primera mitad del siglo XX.

1. Introduction

In this paper, our aim is to discuss and assess advice on correct food from a specific source: a sample of handbooks of domestic economy written for the teaching of girls (and for the teachers in charge of this subject 1) published in Spain during the last 50 years of the 19th century and the first 50 years of the past century. We shall also consider some books written not only for schools but also for a wider audience. We must bear in mind that some of these handbooks enjoyed an enduring longevity. Probably the best example was the book Guide for the housewife. Principles of hygiene and domestic economy applied to morality 2, written by Carlos Yeves (1822-1882), with editions from the mid-19th century to the beginnings of the 20th century 3. Other examples of works with numerous editions in the 19th and the 20th centuries were the publications by Andrés Fernández Ollero 4, Juan Francisco Sánchez-Morate 5 and Victoriano Fernández Ascarza (1870-1934) 6, all of whom were prolific in producing works on the teaching of a number of topics.

Other handbooks survived the crisis of the Civil War and were thus used in very different contexts before and after the war. A good example of this was the Domestic economy by Adelina Estrada 7, one of the authors who fought to improve the level of teaching in this discipline in the 1920s 8. Another instance was the work of Teresa Recas de Calvet Home lessons: notes 9, although in the case of this author, the editions published after the Civil War (1936-1939) underwent some amendments in order to bring the messages into line with the ideology of the new regime. The following quotation, in which the author describes the setting up of Home Schools in the Las Ventas prison for women (Madrid), illustrates the point:

"Therefore, while they are trained in tasks suitable for women, they will also undergo spiritual improvement. Through their work they partially redeem their sentence. When they return home they will take with them a reformed conscience and spirit. So many girls would have followed a different path if only they had had guidance, training, a clear concept of Christian morals and an exemplary mother!" 10.

Of course, our sources are a product of the socio-political context in which they were written. For example, if we link the efforts to improve education with legislation seeking to fight the main threat to public health, we can find initiatives more or less within the same chronology as those passed in the mid-19th century. Another example was that, in an atmosphere of regeneration in the country, several acts were passed to improve the health of the population. As in the case of schools, it was during the Second Republic that public health was considered especially important, and a variety of measures were implemented to ameliorate the health of Spaniards 11. The longest lasting handbooks come from the conservative period of the Restoration and survived while this political system ruled Spain. At the same time, other pedagogical proposals were being put forward that were different in nature. Some, such as the Institución Libre de Enseñanza (ILE) from 1886, achieved great importance, especially among the elites. Others appeared at the beginning of the 20th century, such as the rationalist school, and gained strength in the 1920s and 1930s in anarchist and socialist environments. We will comment on these when we discuss the chronology of the handbooks under consideration.

The domestic economy handbooks have already been used by authors to analyze other aspects such as the teaching of hygiene 12, the indoctrination of women as mothers 13 and the training of women who are to be confined in the household 14. In this context, we should point out that the books analyzed did not contribute to a change in the traditional division of roles between men and women. Men worked in the public sphere and their work was considered as "productive". They were in charge of making a living for their family, but their duties finished with this task. The money was administered by women and they were in charge of all house-keeping tasks. This unproductive work, invisible to society but critical for the support of the national economy 15, followed the traditional division between culture and nature. The handbooks of domestic economy did not break with this traditional way of thinking. Although they were theoretically written for all the social classes, their main target was the lower classes, and they made great demands on women who frequently also worked outside the home. We focus on the contents concerning food; however, there is a large amount of information related to other aspects in domestic economy handbooks to be analyzed, as we show below 16.

It is important to bear in mind that although the majority of the books were written by men, an important number were still written by women. They maintained the traditional discourse of the confinement of women to the private sphere, but at the turn of the century some female writers, without abandoning this discourse (they were also the product of a time and a traditional symbolic separation of roles), began to open up, timidly, other roles for women in the public sphere 17.

We understand domestic economy as all of the skills required to perform all housework: the care of the house and clothes, all questions related to diet -buying and preserving food, kitchen utensils, cooking and so on, managing the household budget, caring for children and the needs of the husband in general.

2. The problem of the sources

We have chosen handbooks on the teaching of girls at elementary schools up to ten or twelve years of age (public and private) 18 and secondary schools, as well as those directed at women in schools and at institutions for the training of future teachers up to 18 years of age, since the school is one of the most powerful tools of socialization and indoctrination 19. Of course, this role of the school must take into account the reality of the country, which had one of the highest rates of illiteracy in Europe. In 1900, 71.4% of women in Spain were illiterate. This percentage only decreased to 47.5% in 1930 20. However, if we take into account the illiteracy rate among girls under 10 years of age, the situation is even worse: 74.5% in 1900 and 52.6% in 1930. In any case, compared with boys, this rate improved significantly during the first third of the 20th century. In 1930, 49.8% of boys were illiterate, and the percentage in the case of the girls was slightly higher, at 52.6%. There was also an unequal geographical distribution, with a clear north-south gradient linked to social, economic and cultural factors. The south (especially Andalusia, Extremadura and Murcia) maintained the highest rates of illiteracy in women, while the North of Spain had the lowest rates. There was also a rural/urban divide. In 1900, 57.7% of women living in the capital of the province were illiterate, a percentage that increased to 75.7% in the rest of the province. In 1930, these percentages were 31.1% and 52.2%, respectively.

We have to link these data to the spread of schools in the country, an aspect that did not merit much attention during the 19th century. The data provided by Rosa Capel on the education of women (table 1) shows the increment in absolute figures in Spain during one period of our study (1900-1930), and the unequal distribution among the different grades and studies.

At any rate, the number of females in schooling during these years represented only a small proportion of those of school age. Thus, in 1910 they represented 23.6% of all schoolchildren, and this percentage rose to 26.5% (nearly 30% if the private sector is included) in 1919/1920.

Regarding levels of education, the training of women was mainly confined to the primary school, although there were some changes during the 19th and 20th centuries, with a slight increment in the percentage of women reaching higher levels of education.

In summary, we are aware that the advice of the domestic economy handbooks only reached a small part of the women's population. Furthermore, as historians, we are highly conscious that the contents of the works do not reflect the reality of the home life of Spaniards. We only consider them, together with other factors of a social, economic, cultural and political nature, in order to understand the changes in the nutritional transition of the Spanish population. The repetition of advice, along with the appearance of new findings in the science of nutrition must have had some influence on the food behaviour of the population. We can quote the example of vitamins: when they made their appearance in domestic handbooks, they set off a "vitamania" (still to be studied in depth) similar to that studied in the United States by Rima Apple22.

Therefore, our sources had two main limitations. They reached only a section of school-age females. From the point of view of their contents, although they were aimed at all social classes, the working class was the principle target. However, we believe domestic economy handbooks and the changes they underwent are a good guide in assessing, in part, trends in the popularisation of feeding behaviour, and as such they deserve our attention. The repetition of the advice of the domestic economy handbooks over a long time span, the increasing role of socialization of schools and the persistence of women's responsibility for home duties -now not only with the weight of tradition, but also with a more or less "scientific" approach to the topic, make the handbooks a privileged source for the study of aspects of advice on the correct use of food.

3. The chronology of the domestic economy handbooks

The works under consideration in this paper are of very varied extension and depth, but they can be classified, from a chronological point of view, into three periods:

3.1. Handbooks published over the second half of the 19th century

We consider here the works written between the General Act of Education of the Moyano Ministry (1857), which made domestic economy (sometimes named domestic hygiene) and sewing and embroidery 23 compulsory disciplines in the syllabus of elementary girls' schools 24. The main goal of these books was to make working class females, as well as women from other classes, active agents in the introduction of domestic life guidelines. They were extremely general, and lacked detail on how to cope with specific areas of the topic. There were, of course, notable exceptions. Most of these publications were only booklets for the use of elementary schools. They were mainly written by teachers or indeed by doctors, as some of them also dealt with subjects regarding health care for babies. Other, usually longer books were written by women and addressed a middle or upper-class readership.

However, there was an important alternative to official education during this period. The Institución Libre de Enseñanza (ILE), already mentioned, was set up in 1886 by professors expelled from the University (including Francisco Giner de los Ríos, Gumersindo de Azcárate and Nicolas Salmerón, former president of the First Republic) for defending Curricular Autonomy and refusing to follow the dogmas of faith required by legislation. They sought to build a new University, but finally were only able to establish elementary and secondary education with a different orientation, methodology and ideology from the official educational system and to introduce modern pedagogical ideas and methods into Spain 25.

The influence of the ILE was enormous and represented a revolution in the educational and scientific environment of the country. In particular, it made possible the training of scholars in other countries and the introduction in Spain of more recent trends in science and art. However, regarding the education of women, it seems the separation of roles continued to be the norm. Members of the ILE aspired to a kind of woman more equal to man but thought of women as a harmonic complement to men. Women were not only destined to marriage, but their traditional roles as wives and mothers were never questioned. However, some revitalizing elements were introduced in order to achieve women who were better trained to fulfil their duties to their husband and children. Over the years, this better instruction led to new training opportunities for women in the professional arena that we cannot describe in detail here 26.

Regarding the content of the handbooks, as mentioned above, the simplicity of the advice was the main characteristic of the books written before 1900. A good example -and the first text we consider- is Notions of domestic economy and household management... written by the famous hygienist Pedro Felipe Monlau. The food-related contents of this type of "notions" 27 usually included: a definition of food and beverages, recommendations on the most suitable type of food, and some indications on how to prepare food and preserve it during long periods of time in order to maintain a larder with basic food such as meat, pulses, eggs and so on. Monlau suggested eating fresh, healthy, clean food with a low level of preparation, but he made a gender difference: vegetables are "better for women than is meat". Fruit was also strongly recommended, although it was important to avoid anything green or overripe.

In general, the handbooks of these years did not support the use of any kind of condiment, sauce or spices, because these substances moved food away from its original state. Only salt received universal approval as a way to enhance the taste of food or to preserve it. Similarly, water was the only beverage that received unanimous endorsement; fresh, clean water with no taste or colour, like crystalline spring water.

Thus, the Lectures on domestic hygiene and economy by Antonio Surós 28, published in 1892 for the training of teachers but also aimed at mothers in general, recommended spring water as the best choice for a beverage, although rain water and river water were also good options.

Another constantly repeated general recommendation was the need to maintain kitchens and kitchen utensils as clean as possible.

A further question was how to decide whether food was contaminated or adulterated. The need to keep food natural and in its original state was the main concern in the transport of food between rural areas and the cities. Domestic economy handbooks distinguished between two forms of alteration. One is the natural time course of food (age, drying, and contamination with dust or insects) that make it unsuitable for eating. This was not the main concern, however, because these changes were generally easy to detect. The real danger was the adulteration of food by artificial methods using a great variety of substances to increase the weight or volume. The books we are considering describe a variety of methods to detect these adulterations, in the hope that the housewife herself will detect the fraud. Evidently, this issue is part of the domestic aspect of the problem studied by Ximo Guillem 29.

Furthermore, all books on domestic economy paid special attention to the distribution of the home budget, seeking to persuade the readership of the advantages of good administration. They also advised avoiding luxury, although it seems the middle or upper middle classes were frequently the target, because the mention of servants was not uncommon.

Reflections on the proper quality of food for maintaining a balanced diet did appear, but at a level that depended on the length of the works.

The handbooks with numerous editions in the last decades of the 19th century were still being published during the first decades of the 20th century. They followed a similar scheme when dealing with food, maintaining outdated ideas, paying little attention to new scientific arguments and preserving the traditional form of advice typical of this period, anchored in common-sense recommendations. They contained references to humoralism, and were heavily loaded with environmentalism and the doctrine of temperaments.

This was the case of the work by Fernández Ollero which was published from the 1870s to 1920 and used for the training of teachers. It was also true of treatise by Carlos Yeves, one of the most re-published books on domestic economy, with editions from the 1850s to 1920; as we have quoted all of his advice was based on experience, with no mention of new scientific principles. As a peculiarity, this text contains suggestions for the raising of poultry (chickens, turkeys, and pigeons).

In the same vein, another important author of this period, Pilar Pascual de San Juan, in her Guidelines for women or lectures on domestic economy for mothers, with editions from the 1870s to the 1920s, strongly recommended simpler foods: pulses, potatoes, meat from the slaughterhouse, cod and eggs, avoiding the delicacies used by the rich inhabitants of the cities and the dictates of fashion 30. Here, she clearly defended food that was cheaper and healthier. She strongly defended the concept that expensive things are unhygienic and immoral.

3.2. Handbooks published from the beginning of the 20th century until the Civil War (1936-1939)

With the turn of the century, there was an important change in Spanish educational regulations. The subject "Physiology and Hygiene" was introduced as compulsory in 1901 in all primary school grades for boys and girls. As a consequence, the position of domestic economy in schools and in teacher training became unclear.

However, most of the works on domestic economy during the first decade of the 20th century were re-editions of books published in the last decades of the previous century, with no amendments to their contents. Nevertheless, some books began to lead domestic economy in new directions. Saturnino Calleja's book, although maintaining an old title, Treatise on domestic hygiene and economy 31, and some of the characteristics of the books of the previous years, introduced numerous physiological concepts in realtion to food, citing the need for the science of chemistry to decide on the best water.

Even clearer were some of the reports published by María Pérez de Mendoza, from the International Congress on Domestic Economy she attended in Freiburg, probably in 1910 32. Some of the chapters dealt with domestic economy in rural schools, and the author highlighted the importance of these schools in Spain, given the rural nature of our country 33. At the First Congress on School Hygiene held in Barcelona in 1912, there were calls for improvements in the teaching of domestic economy. Other authors such as Melchora Herrero, Julia Alegría, and Pilar Rojo played an active role in the section devoted to domestic economy at the Fourth International Congress of Popular Education held in Madrid in 1913. They presented projects and plans to make the teaching of domestic economy "scientific".

The books published in the second decade continued in the same direction, introducing new scientific concepts regarding food. For the first time, references were made to calories, albuminoids and proteins, fat and carbohydrates, among others. The nutritional and energy values of food were discussed, and a balanced diet based on these parameters was recommended.

A good example of the gradual introduction of nutritional findings into domestic economy books is the Brief course of domestic economy and hygiene, childcare and economy for the household schools, published for the first time in 1911 by Melchora Herrero 34. The author described the physiology of digestion, the different components of food, the need for a mixed diet, the necessary daily intake of calories (2,000 with a supplement of from 1,000 to 2,500 when strong physical effort was required) and so on. She also explicitly discouraged antiquated advice printed in previous books on the subject. She recommended following the research and notions of science, eating food as true as possible to its natural state, and she praised dietary simplicity. The presence of science (bacteriology in this case) was also prominent in the usual chapters devoted to the preservation of food, citing pasteurization as the best method to ensure safe milk. Another work that followed this trend was the one published for the first time in 1918 by Adelina Estrada 35. Other works presented a blend of concepts, introducing some new ideas but maintaining old ones, especially with respect to menus and the preservation of food.

Another major concern in this new generation of handbooks on domestic economy was the generalization of its teaching throughout the country and especially in the rural milieu. At the level of female schoolteachers, the subject was reintroduced in 1914, after an absence of 10 years. Published in 1915, the work of Juana Sicilia, Notes on domestic economy 36, advocated the extension of the teaching of domestic economy, describing different trends and possibilities from both Europe and North America. From the USA, she took the idea that teaching domestic economy needs a strong practical side. However, aware of the backwardness of Spain in this matter, she was not optimistic about the possibilities of offering suitable practice. She even proposed using the teacher's home as a laboratory for experiments based on the theoretical contents of the subject. Adelina Estrada, mentioned above, included questionnaires and kitchen and laboratory exercises in her treatise to facilitate practical teaching of the matter.

The preference for food as near as possible to its natural state was omnipresent in the works under consideration. To achieve this goal, women living in the cities were advised to obtain seasonal food and to preserve it under conditions similar to those at the time of acquisition. Regarding rural women, some works claim that they were in the best position to enjoy a healthy diet, although poverty and ignorance formed a powerful enemy alliance.

Hence, the main goal of the works published during the first three decades of the 20th century was make domestic economy a scientific subject, and they began to introduce the new findings of nutrition science. These books had a very clear pedagogical objective, and their contents included how to teach domestic economy. The most representative exponent of this trend was probably Rosa Sensat (1873-1961) 37, who published a long article on How to teach domestic economy in 1927 38, with a second edition in 1932 39. Rosa Sensat, with other teachers, made a tour of France, Switzerland and Germany, visiting nearly 30 schools. A description of this exploratory journey was published in 1912 40. Other reports giving exhaustive information on European experiences were published in 1916 by Dolores Villan Gil in her Notes on domestic economy 41, and by Dolores Nogués Sardá, who wrote a book in 1928 describing domestic science teaching methods in several European countries 42.

The practical side of this teaching was highlighted by presenting the kitchen as the focal point of the household. Basing the work carried out in the kitchen on the natural sciences (physics, chemistry, etc.), they sought to transform it into a kind of home laboratory. In fact, there were several proposals to build schools with a kitchen and a larder attached to the classroom in order to offer practical activities in suitable settings. The main goal of this movement was to improve the training of the teachers of domestic economy, and they including the discipline as a separate subject in their courses. Teachers had previously conveyed only a general idea on traditional ways to organize housework.

Rosa Sensat advocated a wider concept proposing "domestic teaching" instead of "sciences in home life", which she had previously used. She proposed a scientific, practical teaching of the subject, basically addressed to primary schools in order to reach the maximum number of girls. She also proposed basing domestic teaching on the teaching of natural sciences (maths, chemistry and physics) and social sciences (morality and sociology). She also put forward a revolutionary syllabus for natural sciences based on their application to food, dress and knowledge of the human being and life at home. In the case of food, she proposed a programme of natural sciences, including the concepts and numerous practical exercises on topics such as albumin, carbohydrates, fat, food preparation, diets, ways to produce heat, preservation of food and cooking. In fact, she had previously developed the program in the book Sciences in home life, published in 1923 in Catalan 43: which based all the explanations of housework on the sciences, and included experiments on every topic.

Other books published during the 1920s and the 1930s were not so strongly based on the natural sciences but continued to introduce scientific ideas into domestic economy.

However, the great novelty in the introduction of concepts from the "new science of nutrition" was the appearance of vitamins. In the works that we have examined, this concept was explained for the first time, at a very simple level, by Avelina Tovar in her Notions of general and domestic economy 44, published in 1931. Together with information on the caloric value of several foods, she also included their content of vitamins A, B, C and D. Henceforth, references to vitamins appeared to be a useful barometer for the assessment of the quality of the handbooks under consideration.

It is worth emphasizing that the goal of making Domestic Economy "scientific" was not accompanied by a proposal to change the role of women in society. Rosa Sensat is again a good example of this. She never questioned that a woman's place was in the home.

At the end of this period, the Republic introduced some significant changes in laws concerning women 45, but in general, as in the rest of Europe 46 and in other contexts 47, there was no practical shift in the household role assigned to women. In any case, we emphasize the important educational efforts made by the Second Republic. As we have already stated, when the Republic arrived there was a high rate of illiteracy and almost half of the school age population was not in education. In order to counteract this situation, the Republic set up 27,000 elementary schools, raised the professional and economic conditions of teachers and supported a unified, religiously neutral school with bilingualism, administrative decentralization and university autonomy. The Civil War did not allow these projects to go ahead, but meaningful advances were made 48.

We must mention that there were other educational alternatives in the first third of the 20th century. One, the Escuela Moderna, sought to educate the working-class in a rationalist, secular and non-coercive way, with no exams and no separation of the sexes. However, the first centre, founded in Barcelona in 1901, was a private one, and only middle-class pupils were able to pay the fees. The political position of the founder, Francisco Ferrer Guardia, was libertarian, secular and anticlerical, and he sought to create an open-air environment for education. He paid much attention to the teaching of hygiene, with an emphasis on a kind of avant-garde ecology and mutualism.

By 1906, there were 36 Escuelas Modernas with more than 1,000 pupils, and there were also courses for adults during the evening 49. These ideas formed the basis for other rationalist schools in other countries and were also an inspiration for the education offered in the Ateneos Libertarios (Libertarian Arts and Science Associations) throughout the country 50, where other authors such as Ricardo Mella 51 and Leon Tolstoy 52 had an influence. However, as in the case of the Institución Libre de Enseñanza, a more egalitarian consideration of women was not accompanied by a significant shift in their education. Ferrer, like his contemporaries, assigned different roles to males and females. For males, he preserved scientific and rational thinking, while women had intuition and affectivity. As a result, the role of women was to educate their children in the idea of progress. Other anarchist activist such as Teresa Claramunt also highlighted the role of women in the socialization of children. The right of women to be free and aware did not take away their main task as transmitters of rationalistic ideas, maintaining the same role as in traditional education 53. In fact, although anarchist women defended the sexual revolution, free love, abortion and birth control, the role of women as mother was important in anarchist propaganda 54. Some examples confirm that the rationalist schools maintained special education for girls in household tasks, although only as a complementary part of their training 55.

For instance, the secular school El Siglo XXI scheduled a series of "Conferences for women and their education" for the 1909-1910 school year, the first of which was on domestic economy 56. Another example, during the Civil War in Catalonia, was the setting up of the Consell de l´Escola Nova Unificada (CENU) based on the principles of the rationalist school. During the first teaching cycles, there was no mention of the teaching of domestic economy, but in the general syllabus of professional studies, published in October 1936, after a preparatory course, there was a second year with several options, all of them characteristic female tasks, including domestic economy.

In the case of the socialists, their alternative for the education of women was inspired by bourgeois republicanism, institutionalism (from the Institución Libre de Enseñanza) and anarchism. As in the rationalist and anarchist proposals for egalitarian education of women, feminist propositions stood alongside traditional views on the role of women as wives and mothers, considered to have an important function in the transmission of socialist ideas to children.

In any case, we must take into account the influence of the Catholic Church among women. While the ideas of female emancipation were viewed with suspicion by their own comrades, the inertia of Catholic ideas was stronger among working women, and there was little room for changing their traditional role 57.

3.3. Handbooks published after the Civil War until the 1950s

The third period, after the Civil War, was characterized by the strict role assigned to women in the new regime. There was a reinforcement of the concept of domesticity and, as a result, the confinement of women to household duties and motherhood was given clear priority in all of the works written during this period. The gender scheme under the Francoist Regime was anchored in the most fundamentalist sexual division, advocating the exaltation of male domination. Responsibility for the education of domestic economy was entrusted to the Sección Femenina, as part of its role in the indoctrination of women in the values of the regime. In this case, we have only examples of girls who were to be trained mainly in secondary schools, although the number of female students at this level was very low, especially in the first years after the war. Nonetheless, there were numerous editions of the Sección Femenina handbooks on domestic economy over the years until the 1970s, when there was a significant increase in the number of females in secondary education. At any rate, the only place for women in Franco's Spain was the household, and women were required by law to give up work when they married. Of course, this applied only to paid work and not to domestic work or caring for children or the elderly. These tasks were the mission of women and did not involve any economic transaction 58. The same occurred with the agricultural work usually done by women. It was considered part of their domestic duties, and they continued performing tasks in the countryside without any economic reward.

During and after the Civil War, Franco's governments regulated the entire educational landscape 59. Compulsory subjects included: politicalsocial education, music, domestic tasks, cooking, domestic economy and physical education. The monopoly over all of this education 60 was in the hands of the Sección Femenina of the new single party set up in 1937, the Falange Española 61.

Despite the apparent variety of subjects, each of them was in fact designed to train girls as housewives in the service of others and for motherhood, although there were other female models contesting this role 62.

Although the monopoly of training in domestic economy was entrusted to the Sección Femenina of the new regime, some books on the topic that appeared in the 1940s were not published by this organisation. The most notable example was the Economía doméstica by Adelina Estrada, with editions in 1940, 1943, 1945 and 1948. The content of these editions was essentially the same as in the aforementioned 1918 edition, but the author introduced new information on vitamins, devoting an entire chapter to the topic, and praised vegetables and fruits 63.

Another book, Household lessons, published in the 1940s, was written by Dolores Nogues Sardá. An entire section of the book was devoted to food and included significantly updated information. Considering content on vitamins as evidence of the modernity of the book, this work was the most complete, including a chapter with some of the latest nutritional findings 64. She disapproved of "natural water" from rain, lakes and rivers. She only accepted water from springs, but the problem was the insufficient supply for the cities, and she subsequently advocated purification measures for water obtained from other sources 65.

However, the work published by the High Council of Women of Acción Católica 66 in 1943, entitled Hogar 67, was poor in content. The only part worth mentioning is a section dedicated to the "rural household", with recommendations for the raising of poultry. The authors justified this section as a complementary benefit, but they made no mention of the hardships of the Spanish people during these years 68.

Another institution of the New Regime that published books devoted to the household was Auxilio Social69, the main care institution under Franco. After conflicts with Sección Femenina, it lost its independence and was placed under the control of Pilar Primo de Rivera, head of the latter institution 70.

The Secondary Education Reform Act of 20 September 1938 made the study of socio-political training, music, needlework, cooking, domestic economy and physical education compulsory for girls. The Primary Education Act of 17 July 1945 established compulsory socio-political training, physical education, introduction to housework, singing and music.

The domestic economy handbooks that we have been able to find 71 published by the Sección Femenina throughout the years of the dictatorship addressed 4th, 5th and 6th year secondary school students and students of commerce and teaching. They were also for use by women participating in Social Service, which was obligatory for unmarried women or widows with no children under 35 years of age. They had to perform social services for six hours every working day over six months and were used as an unpaid work force. They also had to learn some tasks related to housework. Naturally, the occasion was also used for the indoctrination of women in the principles of the new regime. Without completing Social Service, women were unable to obtain certain jobs or qualifications, to work as a civil servant or to obtain a driving licence. Nevertheless, historiography now considers that the impact of this Social Service was less important in real life because of the large number of women who managed to avoid it 72. It was very difficult to implement, especially in the rural milieu 73, although the Itinerant Training Services 74 and the possibilities of fulfilling the Social Service in this institution gave more rural women the opportunity to comply with this obligation and to obtain training in household tasks and farming techniques.

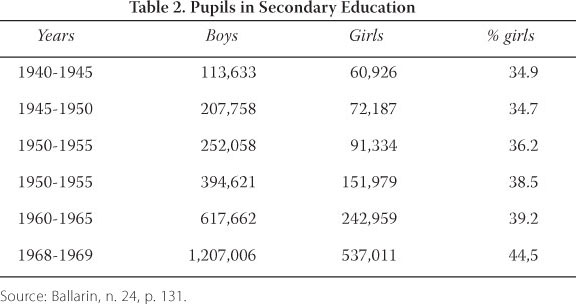

We have to take into account the number of women in Secondary Education in these years in order to estimate the readership of the handbooks published by the Sección Femenina 75:

The handbooks published by the Sección Femenina on domestic economy did not provide any information on food. Although they contained the usual lessons on clothes, ironing, the household, domestic medicine and so on, they had more in common with books on good manners and entertaining than with the domestic economy books of previous decades. The woman that appeared in these handbooks was clearly an upper-class woman concerned with how to set the table and with etiquette.

The Cooking handbook76 was published by the Sección Femenina for the same readership as that of the domestic economy handbooks. It is entirely devoted to food and cooking and gives similar information to that in handbooks published before the war and in the 1940s, but in a more simplified manner. For example, the chapter on vitamins did not appear in one of the first editions of the handbook, and when it did appear, it was very brief and schematic and much poorer than in most of the pre-war handbooks and in non-official works that appeared in the 1940s 77.

In contrast, Housewife. Summary of domestic economy 78, published by Pilar Bartina in 1961, had a very respectable scientific level in relation to food and included an updated chapter on vitamins together with the usual data on caloric values and the information needed for balanced diets.

4. Concluding remarks

We can state that after the poverty of the handbooks written in the second half of the 19th century and still used in the first decade of the 20th century, the handbooks written in the 1920s and the 1930s introduced contributions from the science of nutrition, throught genuinely revolutionary plans for the proper teaching of household sciences. These projects were swept aside by the Civil War, and the official texts, in the case of food, regressed several decades to a world of good manners and etiquette. However, despite the setback caused by the Civil War, some books maintained a good level of information, outside the monopoly of women's education exerted by the Sección Femenina.

Although we are aware of the problems of sources, repetition of the advice on proper feeding and the increase in the proportion of girls attending school over the years under consideration played a role in the introduction of concepts from the new science of nutrition among girls and had a positive influence on the health transition of the Spanish population.

References

1. The only article focused on domestic economy treatises based its conclussions on a very small sample of handbooks and did not analyze the changes produced by the Civil War: Carreño, Miryam; Rabazas, María Teresa. Los manuales de economía doméstica: una preparación exigente para un trabajo no remunerado. In: Museos pedagógicos. La memoria recuperada. Zaragoza: Departamento de Educación, Cultura y Deporte; 2008, p. 336-350. [ Links ] The bibliography on food is wider in Spain, but it is much more developed in the Anglo-Saxon world. See, for example, "American Foodways Biblography", including especially interesting books by Harvey Levenstein and Amy Benteley, in: (http://www.lib.unc.edu/coursepages/amst/S10_amst375/foodbibliography.html) (cited 12 February 2010). [ Links ]

2. Yeves, Carlos. Guía del ama de casa o principios de economía e higiene domésticas con aplicación a la moral relacionados con todos los demás deberes de la madre de familia y reglas generales que cumplir con ellos. Madrid: Librería de Hernando y Compañía; 1902. [ Links ] We have used also a facsimile edition published by Altafulla, Barcelona, 2000.

3. We have found editions in the main libraries of the country published in 1861, 1871, 1876, 1879, 1882, 1885, 1888, 1892, 1897, 1902 and 1913, but there were probably more.

4. Fernández Ollero, Andrés. Breves nociones de higiene y economía domésticas a propósito para las aspirantes al Magisterio y las Escuelas Públicas de Niñas por... Valencia: Imp. de S. Amargós; 1877. [ Links ] We have found editions published in 1873, 1877, 1890, 1891, 1902 and 1909. Throughout this chapter, we quote the edition we have used most frequently, although we have compared it to the other editions.

5. Sánchez Morate y Martínez, Juan Francisco. Ligeras nociones de Higiene y economía doméstica para uso de las niñas que concurren á las escuelas de primera enseñanza. Madrid: Librería de los Sucesores de Hernando; 1909. [ Links ] We have found editions published in 1880, 1905, 1915, 1909 and 1910, but there were many more.

6. Fernández Ascarza, Victoriano. La niña instruida. Fisiología e higiene con aplicación a la economía, medicina y farmacia domésticas, dispuestas para la lectura y estudio en las escuelas y colegios de niñas. Madrid: El Magisterio Español; 1931. [ Links ] We have found editions published in 1900, 1901, 1903, 1929, 1931, 1933, 1939 and 1957, but there were many more, since the edition we managed to find (1931) is the 17th edition.

7. Estrada, Adelina. Economía doméstica. Barcelona: Industrias Gráficas-Seix Barral; 1918. [ Links ] We have found editions published in 1918, 1919, 1924, 1931, 1936, 1940, 1943, 1945 and 1948.

8. Estrada, n. 7, p. 5-6.

9. Recas, Teresa. Enseñanzas del hogar: apuntes. Barcelona: Casa Provincial de Caridad; 1944. [ Links ] We have found editions published in 1924, 1943, 1944, 1946 and 1948.

10. Recas, n. 9, p. 33.

11. We have no room in this article to develop in detail an exploration of parallels between the education policies and other welfare policies. In the case of health, there is abundant literature. A synthesis is available in: Rodríguez Ocaña, Esteban; Martínez Navarro, Ferrán. Salud Pública en España. De la Edad Media al siglo XXI. Granada: Escuela Andaluza de Salud Pública; 2009, p. 49-83. [ Links ]

12. Alonso Marañón, Pedro Manuel. Notas sobre la higiene como materia de enseñanza oficial en el siglo XX. Historia de la Educación. 1987; 6: 23-42. [ Links ] Montero Pedrera, Ana María.; Calderón España, María Consolación. El currículum de enseñanza primaria en España durante el siglo XIX. In: IX Coloquio de Historia de la Educación. El currículum: historia de una mediación social y cultural. Granada: Universidad de Granada, Instituto de Ciencias de la Educación; 1996, vol. 2., p. 249-256. [ Links ] Corts Giner, María Isabel. Acreditación de la higiene como disciplina en el currículum de educación primaria y educación secundaria. In: Terrón Bañuelos, Aida et al., eds. XI Coloquio Nacional de Historia de la Educación. Oviedo: Sociedad Española de Historia de la Educación; 2001, p. 96-105. [ Links ]

13. Uribe Etxebarria Flores, Arantxa. La transmisión de la puericultura por vías escolares. In: IX Coloquio, n. 12, p. 101-110. [ Links ] Palacio Lis, Irene. "Consejos a las madres": autoridad, ciencia e ideología en la construcción social de la función materna. Una mirada al pasado. Sarmiento. 2003; 7: 61-79. [ Links ] Palacio Lis, Irene. Mujeres aleccionando a mujeres. Discursos sobre la maternidad en el siglo XIX. Historia de la Educación. 2007; 26: 111-142. [ Links ]

14. Cortada i Andreu, Esther; Macià i Encarnación, Elisenda. Escola, ciencia i llar: la nova economía doméstica i la formación del professorat Ménager. Educació i cultura, revista mallorquina de pedagogía. 1990-1991; 8-9: 115-121. [ Links ] Ballarín Domingo, Pilar. Las escuelas de niñas en el siglo XIX: la legitimación de la sociedad de esferas separadas. Historia de la Educación. 2007; 26: 43-168. [ Links ] See also, on this topic, other sources: Gómez Gómez, Carmen. La mujer en la política laboral del fascismo a través de la Revista de Sanidad e Higiene Pública. In: VI Jornadas de investigación interdisciplinaria sobre la mujer. El trabajo de las mujeres: siglos XVI-XX. Madrid: Universidad Autónoma de Madrid; 1987, p. 198-207. [ Links ]

15. Durán, María Ángeles. El ama de casa. Crítica política de la economía doméstica. Madrid: Zero; 1978. [ Links ]

16. Carreño; Rabazas, n. 1, p. 338-341. These authors recognize the scientific approach that some of the handbooks of domestic economy add to the traditional and invisible way of considering the work of women at home, but the absence of any mention of the works of Rosa Sensat is surprising.

17. This argument is fully developed by Flecha, Consuelo. Mujeres educando a mujeres: autoras de libros escolares para niñas. In: Guereña, Juan Luis; Ossenbach, Gabriela; del Pozo, Ma del Mar, eds. Manuales escolares en España, Portugal y América Latina (siglos XIX y XX). Madrid: UNED; 2005, p. 49-67. [ Links ]

18. Texts to be used in schools, both public and private, must be approved by the educational authorities: Alonso Marañón, n. 12.

19. Álvarez Uría, Fernando; Varela, Julia. Arqueología de la escuela. Madrid: Las Edciones de la Piqueta; 1991. [ Links ]

20. Capel Martínez, Rosa. El trabajo y la educación de la mujer en España (1900-1930). Madrid: Ministerio de Cultura; 1982, p. 359-356. [ Links ] The author highlighted the difficulties in some cases in obtaining realiable data, but in her opinion, the statistics available are sufficient to show the trends in illiteracy and education of women. For the period under Franco, see Gracia, Jordi; Ruiz Carnicer, Miguel Angel. La España de Franco (1939-1975). Madrid: Síntesis; 2004, p. 105-125, [ Links ] and, especially, Ballarín, n. 14, p. 111-138.

21. The author points out a lot of nuances in these statistics, but we prefer to omit these specifics in order to take into account only the trends in the education of women during the first third of the 20th century.

22. Apple, Rima D. Vitamania: Vitamins in American culture. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press; 1996. [ Links ]

23. Flecha, Consuelo. Los libros escolares para niñas. In: Escolano, Agustín ed. Historia ilustrada del libro en España. Del Antiguo Régimen a la Segunda República. Madrid: Fundación Germán Sánchez Ruiperez; 1997, p. 507-509, 516. [ Links ] This author considered the books of domestic hygiene as the works of reference for scholarly books dedicated to girls.

24. Ballarín Domingo, Pilar. La educación de las mujeres en la España contemporánea. Madrid: Síntesis; 2001, p. 33-57. [ Links ]

25. There is an extensive bibliography on the ILE. See Jiménez Landi, Antonio. Breve Historia de la Institución Libre de Enseñanza. Sevilla: Consejeria de Educación de la Junta de Andalucía; 1998. An updated version (cited, 25 Nov 2009) is available in: http://www.fundacionginer.org/bibliograf.htm and http://www.fundacionginer.org/bibliograf.htm (cited 5 April 2009). [ Links ] For some of the topics related to this chapter see Ballester, Rosa; Perdiguero, Enrique. Salud e instrucción primaria en el ideario de la Institución Libre de Enseñanza. Dynamis. 1998; 18: 25-50. [ Links ]

26. Ballarín, n. 24, p. 68-72.

27. Monlau, Pedro Felipe. Nociones de higiene doméstica y gobierno de la casa. Madrid: Imprenta Rivadeneyra; 1861. [ Links ]

28. Surós, Antonio. Lecciones de higiene y economía doméstica para uso de las maestras de Primera Enseñanza y madres de familia. Barcelona; Plaza & Janes, 1892. [ Links ]

29. Guillem-Llobat, Ximo. Alimentación y sociedad: Prácticas y discursos en la España de la primera mitad del siglo XX. Valencia: Universitat de Valencia; 2008. [ Links ]

30. Pilar Pascual de San Juan did not explain the food that she considered popularised by the dictates of the fashion but included a sentence clearly opposing this kind of food: "healthier food is precisely cheaper food, which means more strength and more health in general for the peasant, who feeds exclusively on pulses, than for the rich inhabitant of the cities, who consumes delicacies". Pascual, Pilar. Guía de la mujer o lecciones de economía doméstica para las madres de familia. 2a ed. Barcelona: J. Bastino e hijos; 1870, p. 31. [ Links ]

31. Calleja, Saturnino. Tratado de higiene y economía doméstica. Madrid: Saturnino Calleja, 1901. [ Links ]

32. Pérez de Mendoza, Miguel. Misión social de la mujer [Social mission of the woman]. Valencia: F. Sempere; 1910. [ Links ]

33. Pérez de Mendoza, n. 32, p. xvii-xx.

34. Herrero y Ayora, Melchora. Curso abreviado de Higiene doméstica, Economía, Puericultura y Educación para las escuelas y el hogar. Madrid: Perlado, Páez y Cía., 1911. [ Links ]

35. Estrada, n. 7.

36. Sicilia y Matín, Juana. Apuntes de economía doméstica para Escuelas Normales de Maestras, Burgos: Marcelino Miguel; 1915. [ Links ]

37. On Rosa Sensat see, among others, Monés i Pujol-Busquets, Jordi. Els primers quinze anys de Rosa Sesat. Barcelona: Edicions 62; 1981, p. 293. [ Links ] González Agapito, Josep. Rosa Sensat, fer de la vida escola. Barcelona: Edicions 62; 1989. [ Links ] Solsona i Pairó, Nuria. La divulgación científica dirigida a las mujeres. In: Álvarez Lires, María, ed. Estudios de historia das ciencias e das técnicas: VII Congreso de la Sociedad Española de Historia de las Ciencias y de las Técnicas. Pontevedra: Sociedad Española de Historia de la Ciencias y de la Técnicas; 1999, vol. 1, p. 591-624. [ Links ]

38. Sensat, Rosa. Cómo se enseña la economía doméstica. Revista de Pedagogía. 1922; 8: 285-295. [ Links ]

39. Sensat, Rosa. Como se enseña la economía doméstica. Madrid: Revista de Pedagogía; 1932. [ Links ]

40. Sensat, Rosa. Viaje pedagógico a Francia, Suiza y Alemania en el año 1911. Memoria presentada al Ayuntamiento de Barcelona por varios maestros públicos. Barcelona: J. Horta; 1912. [ Links ]

41. Villán Gil, Dolores. Apuntes de economía doméstica para escuelas normales de maestras. Valladolid: Viuda de Monter; 1916. [ Links ]

42. Nogués Sardá, Dolores. Organización, métodos y programas de la enseñanza de las ciencias y las artes del hogar: en Bélgica, Suiza, Holanda, Francia, Inglaterra e Italia. Con un apéndice sobre la alimentación del hombre. Ávila: Tipografía y Encuadernación de Senén Martín; 1928. [ Links ]

43. Sensat, Rosa. Les ciències en la vida de la llar. Barcelona: Publicacions de l'Editorial Pedagógica; 1923. [ Links ]

44. Tovar Andrade, Avelina. Nociones de economía general y doméstica. Huesca: Editorial V. Campo, 1931. [ Links ]

45. Genevois Bussy, Danièle. Mujeres de España: de la República al franquismo. In: Duby, Georges; Perrrot, Michelle. Historia de las mujeres en Occidente. Madrid: Santillana; 1993, vol. 5, p. 203-222. [ Links ] Nash, Mary. Maternidad, maternología y reforma eugénica en España. In: Duby, Georges; Perrrot, Michelle. Historia de las mujeres en Occidente. Madrid: Santillana; 1993; vol. 5, p. 627-646. [ Links ] Aguado, Ana; Ramos, María Dolores. La modernización de España (1917-1939). Cultura y vida cotidiana. Madrid: Síntesis; 2002, p. 203-221. [ Links ]

46. Starks, Tricia. A revolutionary home: Housekeeping and social duty in the 1920s. Revolutionary Russia. 2004; 17 (1): 69-104. [ Links ]

47. López, Oresta. Prescripciones y técnicas de higiene doméstica a través de las lecturas para mujeres mexicanas. Latin American Studies Association. XXII International Congress. Miami, Florida, March 16-18, 2000, (cited 25 Nov 2009). Available in: http://lasa.international.pitt.edu/Lasa2000/OLopez.PDF. [ Links ] Ortiz Cuadra, Cruz M. La economía doméstica sobre el papel: La enseñanza de las Ciencias del Hogar en las escuelas públicas de Puerto Rico entre 1903 y 1931. Exegesis, 1997 (cited 25 Nov 2009). Available in: http://cuhwww.upr.clu.edu/exegesis/ano10/v27/cortiz.html. [ Links ]

48. Ballarín, n. 24, p. 86.

49. Sola Gussinyer, Pere. El honor de los estados y los juicios paralelos en el caso Ferrer Guardia. Un cuarto de siglo de historiografía sobre la "Escuela Moderna" de Barcelona. Cuadernos de Historia Contemporánea. 2004; 24: 49-75. [ Links ]

50. Lázaro Llorente, Luis Miguel. Movimiento obrero y educación: las escuelas laicas y racionalistas en Valencia (1880-1914). Anales del Centro de Alzira de la Universidad de Educación a Distancia. 1982-1983; 3: 141-169. [ Links ]

51. Mella, Ricardo. Cuestiones de Enseñanza Libertaria. Bilbao: Zero; 1979. [ Links ]

52. Téllez Benítez, Natalia. Las águilas vuelan solas, las ovejas necesitan de un pastor: la experiencia educativa de León Tolstoi en Yasnaia Poliana. In: Pérez Galán, Rafael; Guerrero López, Jose Francisco, eds. La pizarra mágica: una visión diferente de la historia de la educación. Málaga: Aljibe; 2004, p. 169-182. [ Links ]

53. Ballarín, n. 24, p. 94

54. Ballarín, n. 24, p. 96.

55. Lázaro Lorente, Luis Miguel. Las escuelas racionalistas en el País Valenciano (1906-1931). Valencia: Nau Llibres; 1992, p. 98-100. [ Links ]

56. Lázaro Lorente, n. 55, p. 134-136.

57. Ballarín, n. 24, p. 96-98.

58. Durán, n. 15.

59. De Puelles, Manuel. La política del libro escolar. Del franquismo a la restauración democrática. In: Escolano, Agustín, ed. Historia Ilustrada del libro escolar en España. De la posguerra a la reforma educativa. Madrid: Fundación Gernán Sánchez Ruipérez; 1998, p. 49-60. [ Links ]

60. Sanz Fernández, Florentino. Las otras instituciones educativas en la postguerra española. Revista de Educación. 2000 (número extraordinario): 333-358. Ballarín, n. 24, p. 120-121. [ Links ]

61. On the Sección Femenina see, among others: Gallego Méndez, María Teresa. Mujer, Falange y Franquismo. Madrid: Taurus; 1983. [ Links ] Rivero Noval, María Cristina. Novias, madres, hermanas y... mariposas. Los años fundacionales de la Sección Femenina. In: Navajas Zubeldia, Carlos, ed. Ensayos sobre el papel de la mujer en la historia contemporánea. Logroño: Instituto de Estudios Riojanos; 2001. [ Links ] Elwood, Sheelagh. Historia de la Falange Española. Madrid: Cátedra; 2001. [ Links ] Richmond, Kathleen. Las mujeres en el fascismo español. La Sección Femenina de Falange, 1934-1959. Madrid: Alianza; 2004 (see also the international bibliography in this book). [ Links ] Sánchez López, Rosario. Mujer española, una sombra de destino en lo Universal. Trayectoria histórica de Sección Femenina de Falange (1934-1977). Murcia: Universidad de Murcia; 1990. [ Links ] Sánchez López, Rosario. Entre la importancia y la irrelevancia, Sección Femenina de la República a la Transición. Murcia: Editorial Regional; 2007 (see the updated references in this book on the Sección Femenina). [ Links ]

62. Ballarín, n. 14, p. 166-168.

63. Estrada, 1945, n. 7, p. 14-19.

64. Nogués Sarda, Dolores. Enseñanzas del Hogar. Madrid: Casa Edit. Hernando; 1946, p. 81-89. [ Links ]

65. Nogués, n. 64, p. 139-142.

66. On the role of women in Acción Católica see: Blasco Herránz, Inmaculada. Dones i activisme catholic. l'Acción Católica de la Mujer entre 1919 i 1950. Recerques. 2005; 51: 115-139. [ Links ]

67. Mujeres de Acción Católica. Hogar. Madrid: Publicación del Consejo Superior de las Mujeres de Acción Católica; 1943. [ Links ]

68. Mujeres de Acción Católica, n. 67, p. 78-95. [ Links ]

69. Onieva, Antonio Juan. ¡Madres! Madrid: Ediciones Auxilio Social. F.E.T. y de las J.O.N.S., Afrodisio Aguado; 1939. [ Links ] Onieva, Antonio Juan. La mujer en la familia y en la sociedad. Madrid: Afrodisio Aguado; 1939. [ Links ] On this publication, see Cenarro, Angela. La sonrisa de Falange, Auxilio Social en la guerra civil y en la posguerra. Barcelona: Crítica; 2006, p. 124-129. [ Links ]

70. Perdiguero-Gil, Enrique; Castejón-Bolea, Ramón. Auxilio Social: Health care and social policies in Spain during and after the Civil War (1936-1939). In: Andresen, Astri et al., eds. Healthcare systems and medical institutions. Oslo: Novus Press; 2009, p. 129-141. [ Links ]

71. We have used the editions of 1950, 1952, 1954, 1961, 1974, but there was practically one edition per year from the 1940s onwards.

72. Muñoz Sánchez, Esmeralda. La Sección Femenina en la transición española. Historia de una organización "invisible". In: Sánchez Sánchez, Isidro. La transición a la democracia en España. Historia y Fuentes Documentales. Guadalajara: ANABAD-Castilla La Mancha y Asociación de Amigos del Archivo Histórico Provincial de Guadalajara; 2004. [ Links ] Rebollo Mesas, P. El Servicio Social de la mujer de Sección Femenina de Falange. Su implantación en el medio rural. In: Ruiz Canicer, Miguel Angel; Frías Corredor, Carmen, eds. Nuevas tendencias historiográficas e historia local en España: Actas del II Congreso de Historia Local de Aragón. Zaragoza: Instituto de Estudios Altoaragoneses, Universidad de Zaragoza, Departamento de Historia Moderna y Contemporánea; 2001, p. 308-309, p. 311-314. [ Links ]

73. Rebollo Mesas, n. 72, p. 304, 310, 314-315.

74. Ballarín, n. 14, p. 126-127.

75. On Secondary Education under Francoism see also: Grana Gil, Isabel. Las mujeres y la segunda enseñanza durante el franquismo. Historia de la Educación. 2007; 26: 257-278. [ Links ] Gómez García, María Nieves. Valor y precio de los estudios de bachillerato en España: apuntes para una investigación. In: Terrón Bañuelos, Aida; Álvarez Fernández, María Violeta; Diego Pérez, Carmen; González Fernández, Monserrat. XI Coloquio Nacional de Historia de la Educación. Oviedo: Sociedad Española de Historia de la Educación; 2001, p. 584-591. [ Links ]

76. Manual de cocina para las alumnas de bachillerato. Madrid: Delegación de la Sección Femenina de F.E.T. y de las J.O.N.S, 6a ed. [ Links ] There were editions of this treatise from 1940s onwards. Manual de cocina para Bachillerato, Comercio y Magisterio. 16a ed. Madrid: Delegación Nacional de la Sección Femenina de F.E.T. y de las J.O.N.S.; 1966. [ Links ] As in the case of the domestic economy handbooks, there were new editions almost every year.

77. See for example: Manual de cocina, n. 76, p. 165-167.

78. Bartina Marull, Teresa. Ama. Resumen de economía doméstica. Gerona: Dalmau Carles Pla; 1961. [ Links ]

Fecha de recepción: 4 de diciembre de 2009

Fecha de aceptación: 11 de febrero de 2010