Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Dynamis

versión On-line ISSN 2340-7948versión impresa ISSN 0211-9536

Dynamis vol.36 no.1 Granada 2016

Pathological anatomy and self-portraiture

Glenn Harcourt (*) and Lisa Temple-Cox (**)

(*) orcid.org/0000-0001-6561-1409. Independent scholar in Pasadena, California. glennrharcourt@gmail.com

(**) orcid.org/0000-0003-0882-359X. Independent scholar and artist. lisatemplecox@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Why should an artist look to anatomical or pathological specimens as a reservoir of images with which to facilitate an articulation of his or her own artistic or personal identity? This is the starting point of a reflection on the disappearance of the artist and its transformation into a passive object. As a result, it is also a reflection into the blurring lines between subject and object. On the grounds of the work elaborated by the artist Lisa Temple-Cox and the critical look and comments made by the observer Harcourt, this paper is a first-hand attempt to understand the configuration of the self and the influence of the artistic intervention in the generation and representation of anatomical knowledge, resulting in an exploration into the intertwined processes that create both historical subjects and historical objects.

Key words: anatomical specimen, pathological anatomy, art, identity, representation, historical subjects, historical objects.

(...)self, no interstices at all, nothing in between.

Lisa Temple-Cox: fragment of a text

Specimens are a lot like words: they don't mean anything unless they're in the context of a sentence or a system, and their meanings are extremely promiscuous1.

1. Introduction

This paper will be grounded in a detailed examination of an apparently straightforward question, but one which we believe can shed considerable light on the way[s] in which the artefacts produced by the generation of scientific knowledge (in this case, anatomical specimens) can be appropriated by artists to radically different ends. The question is simply this: Why should an artist appropriate specimens of pathological anatomy as a reservoir of images with which to facilitate an articulation of his or her own artistic or personal identity?

This question is of interest for at least two historically important reasons. First, because it involves a radical reconfiguration of the way in which artists have traditionally conceived of themselves as active and intellectual beings (an artist can be identified by intellectual activity and artistic practice). This conception is now replaced by one in which "identity" becomes something that can be trapped only in a shadowy liminal realm where light and life fade into death and darkness: where the active, creating self of the artist becomes a passive object, a pathological specimen, a thing rather than a being. Second, this transformation also inverts the standard paradigm for the generation of anatomical knowledge (and to a great extent of medical knowledge in general): a paradigm wherein a more-or-less strict separation between the inquiring subject and the object of inquiry, between anatomist (or anatomical draughtsman) and cadaver or specimen must be maintained, in order to mediate the fact that the anatomist's knowledge is constituted through the systematic destruction of an object that is also already an [ex-]subject, a once living human being.

This kind of appropriation is now widespread, and has infiltrated any number of cultural contexts. However, we will focus initially on work produced by one of us, Lisa Temple-Cox, in which she posits or represents herself as an anatomical or pathological specimen. This body of work will be examined both from the perspective of the artist, and from that of an outside historically-situated observer (Harcourt), whose observations will constitute a dialogue in which we will seek to discover the extent to which the work might constitute 1. an index of purely personal alienation or 2. an attempt to recast the self as a thing socially constructed as something foreign, alien, ethnically and ideologically "other". Finally, we will examine (briefly) the possibility that this kind of artistic intervention has had an influence back on the representation of anatomical knowledge, and whether the hard-and-fast subject - object distinction that has characterized the generation of that knowledge might itself be undergoing a reconfiguration.

2. Life and death masks

The eyes, those "windows of the soul", are closed. Perhaps a little tense, the features are nevertheless composed as if in sleep, or death (figure 1). The portrait indeed captures the artist's own visage. It has a kind of gritty realism. However, on closer inspection, this realistic surface turns out to record artefacts of the casting process at least as frequently as it does the minute details of the artist's physiognomy. The portrait is thus emotionally and psychologically blank, as such castings almost necessarily are. It inhabits a kind of liminal existential space: part artefact - part portrait; all surface and no depth; physiognomy without psychology; an image of death in life or of a slumbering life that mimics death.

Figure 1. Lisa Temple Cox: series of "Life and Death masks" (2011)

that captures the artist's own visage with the skeleton of a pair of

conjoined twins housed at the Mütter Museum of the College of

Physicians of Philadelphia. Collection of the artist.

But this is not the entire story. For the face also presents itself as both a "blackboard" and a "screen". On the "board" is inscribed a text, written by the artist: "what if the weather map of your emotional life was engraved upon the very skin of your face?". Aside from a distant echo of Franz Kafka's horrific "In the Penal Colony", what exactly does this inscription tell us? First of all, that the emotions themselves, whatever they might be, are to be resolutely unexpressed. The mask remains passive, while the artist's internal emotional life is literally spelled out in the text. The play of emotions is imagined metaphorically in terms of the conventional marks that correspond to the atmospheric disturbances recorded on a weather map.

Meanwhile, slicing vertically across the entire right side of the face we see an image projected as if onto a screen. This is the artist's absent body, the image of an actual skeleton correlated with the metaphorical fiction of the emotional map. But, whereas the metaphor of the map unfolds the subject's turbulent emotional life through the acts of inscription and reading, the depicted skeleton is rather a static "portrait"2, which belongs to the world of pathological or teratological anatomy. What we see is a pair of conjoined twins displaying the condition known as cephalothoracopagus monosymmetros (where the area of fusion comprises the head and thorax) now housed in the collection of the Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia3.

It is, perhaps, not immediately clear why the artist might have chosen to project such an apparently self-alienating vision of her own body, subjecting herself to an objectifying identification with a pathological museum specimen. Conversely, her choice seems to endow that specimen with a kind of second-hand life. Indeed, she provides a vivid or living presence to an object heretofore invested, at best, with a kind of unrealized subjectivity, a self-hood terminated at the moment of its birth as nature morte, dead on arrival. It is the aim of this paper to make some coherent sense of this choice and its implications. We hope also to provide at least the outline of a context within which to understand the practice of artists whose work either suggests or insists on an identification of the self as a pathological construct, the being of an "Other" constituted by a particular medical gaze and discourse. Although originally historically grounded4, that construction is now, in our post-modern world, something readily available for appropriation and re-configuration. It has become an Other just like any other Other.

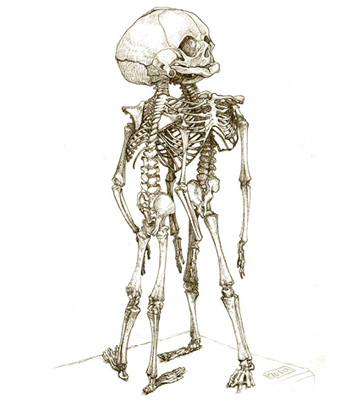

Returning to the inscribed and desecrated mask, we can suggest a provisional description of the "self" projected by the work as a whole. That self is obviously fragmented in a much more radical way than even the Cartesian mind-body dualism of the Enlightenment might suggest or encourage5. The body itself is either absent (leaving only the decapitate head behind the mask) or envisioned as a deformed self-parody. At the same time, the pathological doubling of the conjoined specimen suggests both an incomplete "tearing apart" or twinning, and an unrealized and equally incomplete fusion. In a related work (figure 2), a variation on the same theme, the pathological specimen, from the collection of the Musée Dupuytren in Paris, is likewise a pair of conjoined [ectopagus] twins, who seem almost to be struggling to effect that final separation, inhibited only by the thorax that binds them together in an awkward and eternal danse macabre.

Figure 2. Lisa Temple Cox: series of "Life and Death masks" (2011)

that captures the artist's own visage with the skeleton of a pair of

conjoined twins housed at the Musée Dupuytren in Paris. Collection of the artist.

3. Ritta Christina: the marvelous two-headed girl

At the time of their collection and preparation in the 19th century, such specimens themselves inhabited a liminal intellectual space, where the categories of "pathology" and "monstrosity", as well as those of "monstrosity" and "humanity", were as yet incompletely differentiated. Although obviously not equivalent, these categories were effectively if incompletely conjoined, rather like the unfortunate twins in Paris and Philadelphia6.

Indeed, such composite beings seem to have posed an on-going problem for the notion of the individual self7. In Ambroise Paré's sixteenth-century world, for example, the heart is the ultimate diagnostic: one heart equals one individual, two hearts indicates two8. Paré discusses a case of parapagus dicephalus twins (twin girls who shared a single body between two heads) where he accepts the report of Konrad Lycosthenes that the singularity of the creature's self-hood, as demonstrated by the singularity of its heart, was reflected as well in a complete uniformity of [thought and] action as between the two heads: "these two heads ([Lycosthenes] says) had the same desire to drink, eat, sleep; and they had identical speech, as also their emotions were the same"9.

This scientific conundrum was still unresolved in 1829, when the anatomist Étienne Serres performed the dissection of the parapagus dicephalus tetrabrachius Ritta and Christina Parodi -thanks to Serres' exhaustive monograph perhaps the most famous set of conjoined twins with the exception of the "Siamese" brothers Chang and Eng. Although Ritta and Christina were clearly distinct individuals with markedly different personalities and physiologies, they passed conjointly away, almost as one: when Ritta died of chronic bronchitis, her sister (apparently healthy) joined her in death within a very few minutes10.

Still, the de facto answer to the one individual or two question seems by then to have been provided under the aegis of the Church through the ritual of baptism. The baptism of conjoined twins insured their generic person-hood, while baptism under two names cemented their duplicate "personality". Still, the confusion over the existential status of Ritta and Christina, the marvellous two-headed girl(s), persisted both throughout her life and beyond its end. This can be seen even by tracking the way in which the twins are characterized in Leroi's modern narrative, where they are sometimes singular in designation, and sometimes plural. His final evaluation: that they were "really" "two girls with one body"11 is certainly borne out by his discussion of the embryological biochemistry that resulted in their coming into being12, although their ultimate fate strips them of flesh, of individuality, and of person-hood tout court. "The anatomists finished their work, and then boiled the skeleton [now an obviously singular object] for display"13. The twins thus came to their final rest as an example of a particular pathology, rather than as a memorial to the end of a life's singular or reduplicated history.

To recapitulate, if the artist's conjoined and appropriated body has thus been radically disfigured, rendered grotesque and monstrous, and finally objectified as a pathological specimen, her self's "interiority" can neither be glimpsed through the resolutely closed windows of the life mask's eyes nor read in the blank passivity of the face. Rather, the possibility of gaining access to that life is literally inscribed on the surface of the face, in a text raised as if embossed on the skin, and pointing obliquely toward the system of conventional signs that constitute the weather map.

Yet, despite all this apparent evasion, all the transformations and inversions and encryptions, at the centre of the work is a life cast of the artist's face, which carries an indexical force similar to that attaching to a photograph. The cast is thus a powerful icon of personal presence with deep historical roots14, and an equally deep if ambivalent resonance. In part, this ambivalence derives from the idea of the cast itself, which can in theory be used to picture either life or death. And it is reinforced by the process of its facture, which necessarily imparts an image of death-like repose to a living subject15.

At the same time, even life masks, thanks to their photograph-like indexicality, are subject to the famous critique advanced by Roland Barthes in Camera Lucida, that the subjects they depict are as if already dead16. The mask thus exists in its own liminal space, demarcating not the line between the "normal" and the "pathological", but instead the line between life and death. Nevertheless, these existential states appear, not so much as opposites (being as opposed to non-being or "self" as opposed to "absence of self") but rather as a pair of mirror images, or conjoined twins.

The appropriation of this kind of imagery suggests the artist's struggle to recuperate that sense of a "self" split by "no interstices" and disrupted by "nothing in between". On the one hand, one possible endpoint of this struggle can be seen in the artist's appropriation of two widely circulated images of the skeletonized specimens that record the flickering existence of conjoined and monstrous twins. On the other, some sense of that struggle as a lived experience can perhaps be glimpsed in the tragic tale of the complex misalliance between Christina and Ritta Parodi, at once singular and twinned, equal and unequal, speaking one life with two voices or two lives as if with one voice. In any case, this tale of the travails of "two girls with one body" can easily be read as a metaphor for the life of "an artist [as Temple-Cox has described herself] whose cultural and social background have already marked her out: privileged daughter of a white patriarch in post-colonial Malaysia, coloured "Paki" in suburban England"17.

In one sense, this is a completely and easily understandable kind of association to make. The fractured sense of identity associated with post-colonial experience, a kind of double alienation and dual objectification (where one is a "product" of two cultures; but feels as if belonging to neither and rejected by both) is elegantly captured and elaborated by the work. And the stakes involved in mediating that feeling of doubled otherness are certainly high.

But it is also an enormously focused association, and one which gives a particular social and cultural inflection to an artistic strategy that seems much more general in its potential associations. It hides as much in potential resonance as it gives away in focus. What we aim to do now is to open up this very precise reading, to broaden our context so as to allow our specimen to speak as "promiscuously" as possible. In doing so, we can begin to measure the extent of the work's entanglement in a broader contemporary visual culture.

4. Institutions and the street

The preconditions allowing for the production of work like Temple-Cox's Life and Death Masks are complex and deeply rooted in art and cultural history. Nevertheless, we can identify as a broad and contemporary contextual frame a certain kind of emergent institutional orientation. Collections of pathological and anatomical material, characteristically held by medical and related scientific institutions, and traditionally "protected" by restrictive conditions of access and use, are in some cases being opened up to an increasingly wide range of patrons who are more-or-less free to engage individual specimens or whole collections and institutions in a variety of culturally resonant ways18.

In the United States, the Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians in Philadelphia has long been a leader in outreach both to a wide general public and to artists, photographers, writers, and film-makers who have accessed its collections in pursuit of material for any number of extraordinary projects and exhibitions19.

In England, an interesting parallel and contrast might be offered by the Barts Pathology Museum of the University of London. Although access to the collection itself is carefully controlled, Barts nonetheless sponsors an enormously wide variety of lectures, events, film screenings, etc. that cover a vast territory of both "popular" and serious topics, often inextricably entwined with one another20.

And these examples might easily be multiplied21. Yet they are still relatively rare instances. Most medical collections remain firmly inaccessible to the public except under specific conditions or licenses, and, at least in the U.K., subject to the provisions of the Human Tissue Act of 2004.

Nevertheless, coincident with these changes in institutional orientation, there has been an equally explosive eruption of natural historical, anatomical, and pathological material into the productions of both high and popular culture. While this cultural production may have been fed and encouraged by institutional contacts, it is hardly dependent solely upon these interactions -it has its own internal dynamic as well- and it is marked by a complex and mutually reinforcing circulation of motifs, strategies, and meanings that produces an entangling web of objects stretching all the way from the studios of "high-end" artists like Damien Hirst through the gift shop of the Mütter Museum to more-and-more relentlessly popular, even "transgressive" venues like tattoo parlours, periodical publications like Juxtapoz22 and the great flood of fan and amateur art that crosses the internet through sites like Street Anatomy (http://streetanatomy.com/)23.

Thus Damien Hirst's "natural history" works, and especially perhaps the 1991 Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living and Away From the Flock (1994) have become icons of this cultural moment; while his Diamond Skull hangs giddily on the edge of macabre (and very expensive) kitsch24. At the same time, monstrous conjoined twins including those appropriated by Temple-Cox from the Mütter and Dupuytren Museums have gained a flickeringly reiterated existence (along with numerous similar specimens, as well as anatomical illustrations from the works of Vesalius, Albinus, and others) as models for tattooed body art, tee-shirt designs, and the like25.

5. Monstrous subjects

Looking at things from a more traditional historical perspective, we can see, in outline, one example of how this transformation from pathological specimen to artistic metaphor has played out by looking at the kind of specimens employed by the artist in her Life and Death Masks: skeletal mounts of foetal and newborn infants, specifically examples from the collection of the Mütter Museum.

A number of specimens now in the Mütter collection were illustrated by Hirst and Piersol in their definitive anglophone atlas Human Monstrosities (1891-1893)26. Of particular interest here is their study of a pair of ectopagus dicephalus dibrachius tripus twins (laterally joined -ectopagus- and possessing two heads, two arms, and three legs)27. The specimen has been photographed against a neutral background, which was then itself blacked out, so that in the final presentation the skeleton stands out as a sepia and brown object against a flat black ground. It thus exists in a non-space, entirely separate from "our" world, as if suspended miraculously in a black void. It inhabits a world in which it is the only extant being. This strategy has the immediate effect of "defamiliarizing" the specimen, of placing it outside our world of lived experience. It can easily be regarded as a "thing", an example of a specific teratological development (today, we would say a specific genetic malfunction) that renders it exemplary of a class (for Hirst and Piersol, literally a "species") of similar objects. This sense of inhumanity is reinforced by the bizarre mis-articulation of the skeleton, which nature has assembled "all wrong" -the vestigial third leg is perhaps especially disconcerting.

It is impossible, however, to efface the sense of humanity completely from the tiny skulls, one of which appears in a pure "classical" profile (in traditional portrait iconography often a commemorative marker), the other of which is shown tipped slightly forward and cocked a bit to one side, as if in contemplation or puzzlement. Since the skulls seem perfectly if incompletely formed, they raise the spectre of a self (or selves) tragically and prematurely snuffed out. This sets up a tension within the image -one that in fact carries through the entire book- which is resolved, in so far as it can be, contextually. We know that this is a medical text which aims to present and explain a certain kind of material, and this enables us to "bracket" that material so as to facilitate the authors' obvious scientific intention28. In effect, it is context that allows us to read the images "correctly". We maintain a critical or scientific distance, while at the same time never quite forgetting or suppressing the humanity of the abortive beings that have become the specimens we actually see.

Not surprisingly, a number of these specimens attracted the attention of the photographers originally commissioned by Gretchen Worden to work in the Mütter Museum collections. Although the strategies employed by the commissioned artists (who were virtually unrestricted in their choice of material and the particulars of their staging) were extremely varied, the work of the artists attracted to the foetal skeletons (both normal and teratological) seems relatively "of a piece" -sharing more similarities than differences.

Scott Lindgren's Cephalothoracopagus (1990) is at once a [double] portrait and a study of a specimen mounted for display29. Although background detail is almost entirely suppressed, so that the brightly lit skeleton is prominently placed against a dark ground, the specimen remains firmly grounded in "our" world, the world of the museum and its by-now antique collections, by means of the wooden base on which the preparation stands, and to which have been affixed various labels and inventory numbers. The figure stands in a classic three-quarter full-length portrait pose, easily achieved by rotating the base with respect to the plane of the picture. Likewise, we can easily see a number of the wires and pins that have been used to secure the preparation. The dark background is also a common Renaissance portrait convention; and the three-quarter view has the effect of presenting the face as [almost] believably human, although that effect is achieved at the expense of a sort of flattening out of the whole head. Not surprisingly, given the condition of the conjoining, the face wears an expression that is also rather flat and affectless, a lack of affect that is carried downward through the whole body, which seems to stand at rest, flat-footed and rather ill at ease.

What differentiates this photo from the photos used to illustrate Hirst and Piersol? More than anything else, a kind of re-contextualization. In the case of Hirst and Piersol, the presentation of the individual photos was highly abstract, the specimens floated as if in an inky void, while the context (the fact that the photo occurred as an illustration to a medical text) was external to the image. In Lindgren's photo, on the other hand, the context is internal to the photo. It exists in the record of the preparation which marks this "portrait" simultaneously as the image of a museum specimen, that is, of a mere thing -a comparison with the skeletal plates from Vesalius' Tabulae sex is especially relevant here30.

Arguably, it is this re-contextualization that facilitates the promiscuity of meaning to which Asma alludes in our opening quote. And it is this promiscuity in turn, that opens up the very interstices Temple-Cox perceives as incompatible with her own sense of self.

For a good image of that interstitial space, we might compare Lindgren's photo to another Mütter image, Gwen Akin and Allan Ludwig's Skeleton No. 3 (a platinum print from 1985) which brings together three of the museum's foetal specimens: the cephalothoracopagus monosymmetros twins, plus a foetal skeleton suffering from clubfoot (talipes calcaneovarus) as well as a final anencephalic foetus with complete spinal bifida (both carefully "disguised" by the staging of the photo)31. On one level, the specimens read obviously as what they superficially are: three mounted foetal skeletons, photographed so that the resultant image seems to carry an air of extreme age, as if the 19th century provenance of the specimens was matched by the antiquity of the photographic record of their truncated existences. It is as if the photograph itself aspires to create its own historicity, embedding itself in fictive time as deeply as the objects it records were themselves embedded in their own temporal realities.

At the same time, the three specimens are posed in a way that apes the arrangement that might mark an actual conversation. The three malformed and abortive infants stand as might three old men (both the appearance of the specimens and the character of the photographic print work to reinforce this sense of agedness) chatting, perhaps on a street corner, their fragile forms bent and twisted now by age rather than deformity, and lit by the flickering light of a street lamp that plays across the night-time blackness. In short, they have as it were acquired a narrative mise-en-scène, an interior context that fundamentally disrupts our understanding of their actual condition. It is the work of the photograph to unmake our expectations; and this happens in a way that grants to the specimens a kind of spurious self-hood, an aged being that exists as if on the brink of death. Such a strategy effectively forestalls the question of the potential selves that may or may not be implied by the existence of the physical beings whose skeletal remains are in fact captured in the photo32.

Temple-Cox's transformation of this appropriated motif, however, is even more radical than is the case for the photographers Lindgren, Akin and Ludwig. In Life Mask I, the cephalothoracopagus foetus appears as a kind of decontextualized sign, which marks or disfigures the white face of the mask like a tattoo. And in that disturbing, disfiguring sense, it can seem, again like a tattoo, to carry a transgressive connotation: if nothing else, it is an affront to the integrity of the face, to its balance and sense of repose -whether in life or in death33.

6. The corporeal body

It may be, however, that this kind of comparison misses an important point: that the changes we have been tracking in visual culture are indexed to an increasing suspicion (even belief) that what lives, suffers, dies, is anatomized, bottled, skeletonized, catalogued, and displayed by medical science or the tattoo artist's skill is not so much a self as something that in fact is irreducibly and brutally physical: to wit, the frankly corporeal body34.

We can perceive this kind of strategy in a work like Eleanor Crook's flayed, anatomized, and disfigured Snuffy (2000: Polyester resin, ½ life-size)35 (figure 3). Despite his putative humanity, Snuffy seems to display virtually no affect, no external quiver or nuance of pose and expression that might suggest an interior life. His most obvious raison d'être seems to be simply the abject display of his more-or-less anatomized jaw, back, and right leg. The left leg has peremptorily been removed and discarded -a macabre literalization of the phrase disjecta membra. Whether or not he retains some "interior sense" of that physical abjection is a moot point.

Figure 3. Eleanor Crook: "Snuffy" Polyester resin, ½ life-size, 2000.

Collection of the artist; used by permission.

Yet Snuffy is explicitly not a specimen or even a waxwork teaching aid. He properly sits in an exhibition space, rather than a lecture hall or an operating theatre. Nor, as might be expected and despite his evident artistry, does he evoke any enduring sense of the Renaissance ideal of a man made in the image and likeness of God. Instead, he seems an embodied metaphor for a strictly carnal rather than an incarnated understanding of man's fleshly being. There is only the prison of the flesh; for the prison and the prisoner are one.

Still, there is a certain ambivalence here; and perhaps necessarily so by virtue of Snuffy's evocation of what we might characterize as the "natural body", with its residual echoes, however distant, mediated, or mutilated of the classical tradition seen as the apotheosis of "naturalism", that supreme fiction of pictorial representation. It is far easier to imagine a stick figure as "soul-less" (or simply as an arbitrary graphic mark denoting "person") than it is even figures as objectified and anatomized as Snuffy.

Indeed, the artistic disruption of the explicitly fleshly body can be carried much further than is the case with Snuffy, but without ever quite escaping this ambivalence. Look, for example, at the work of Berlinde De Bruyckere. Images of bodily fragmentation and dissolution abound there. Distressed bodies are split open, their insides spilling out, as bloody tentacles writhe and antlers prod dangerously. Apparently anencephalic adults burrow into enormous pillows as if in mindless terror. Even gigantic hanging and conjoined fragmentary horses are cast by the artist as actors in a complex, erotic, compassionate and very emotional world that resonates deeply both with the artist's personal history and with the overlaid histories of western art and culture.

In speaking of her 2012 installation, We are all Flesh36 at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Berlinde De Bruyckere makes it perfectly clear that her work is intended to evoke a stark brutality, a savagery which often spills out into the open because "we can't control the inside [of the body]" -its most hidden biological recesses and the site of its pathological deformation. Yet she also argues that the same work is intended to celebrate not only the "self", but the interaction of "selves" as well. This interaction takes on an almost sacramental character (the artist compares the exhibition space to the interior of a church with its high altar and side chapels) where we celebrate, among other things, "the very fragile moment when two human beings become one", often in a way that echoes, if distantly, the conjoined twins of Temple-Cox's Masks. This is a place where the terrified anencephalic burrower, is received, swallowed up, by his sheltering pillow "as if by a lover". Finally, and perhaps most importantly for us, it is a place where we are meant to come to the realization that "we [our bodies/our selves] are built out of [the] parts of others"37.

On one level, this realization certainly seems to contradict Temple-Cox's expressed desire to discover (or represent) a presumably integral "self" containing "no interstices", and with "nothing in between". Yet this desire may itself be an instance of the truth of the old adage "Be careful what you wish for".

One of the most starkly terrifying of the works in a career containing many such epiphanic moments, Edward Kienholz's 1966 concept tableau entitled The State Hospital displays an image of the self perfectly recapitulated by an act of imagination that models or doubles the act of artistic creation38. In order to access the significant image, an observer peers through a barred doorway into a mock-up of a room in a state mental institution, where a naked and brutalized inmate lies strapped to a filthy bed by his bound wrists. His face has been replaced by a fishbowl in which goldfish placidly swim. He seems the perfect image of abjection and desolation, his world defined by the hard flatness of the bed, his universe by the boxy confines of the room. He is perfectly alone, except for a strange twin, a dream doppelgänger framed by a neon "thought balloon" who lies strapped to the top bunk of the dilapidated bed. And although the patient can hold his "twin" in memory or imagination, the two are absolutely cut off from one another both by the structure of their world and by their own immobility. Indeed, the patient has constructed for himself a meticulous "self portrait", perfectly self-referential, composed of no "parts" and with "no interstices" nor "in between". Trapped in an eternal present of suffering, the patient has replicated his "self" as a disjoint and isolated twin, and both are and will remain virtually entombed in the cell marked on the outside WARD 19. How much more inviting the open vitrines of Berlinde De Bruyckere's We are all Flesh?

At the beginning of our inquiry, we looked at two works, from the series of Life and Death Masks, where the face itself was the primary ground on which the drama of the self was at once articulated and staged. More recently, we have encountered other sites for the staging of the self: the gallery, the vitrine, the supporting cradle and the [sheltering] pillow, the "church", the solitary hell of the locked mental ward. Now, we turn to a further interconnected three: the studio, the laboratory and the museum.

7. Making myself a monster

Temple-Cox's An Order of Things (2009-2010) is a complicated installation that has received a number of different iterations39. Attempting to disentangle and account for all of its ramifications is far too complex a task to undertake here; so we will concentrate on just two or three, evoking other details as necessary.

Although less meticulously specific than Keinholz's State Hospital, the installation is nevertheless ideally staged in a semi-enclosed space that is redolent of the whole somewhat archaic milieu within which the study of pathological anatomy was constituted as a practice, and from which it has (mostly) passed into essentially archival settings suggestive of storage and display40.

Despite the multiplicity of its component parts, we want to concentrate here on one particular ensemble: a cabinet containing two superposed pairs of watertight specimen jars, into three of which were placed plaster casts of the artist's head, each head submerged almost to the level of the nostrils in a different and differently coloured fluid. The cabinet was provided with interior lighting, so that in a relatively darkened and secluded space the specimens in their fluids seemed to glow with an ethereal and disconcerting light that rendered the "collection" decidedly macabre, and yet strangely sacral as well (figure 4).

Figure 4. Lisa Temple Cox: cabinet with plaster casts of the artist's head.

This is part of the installation "An Order of Things", exhibited at Minories

Gallery in Colchester, England, 2009-2010. Collection of the artist.

Following the initial creation of a three-part mould of the artist's shaved head, the design of this part of the work, which had originally envisioned heads ("selves") cast in a variety of "abject" and/or organic materials (clay, wax, shit, fat, etc.) was radically reconfigured in a direction that changed both process and meaning in fundamental ways41. There was now to be but one overt and reiterated evocation of "otherness", comprising the contrast between the artist's own skin and the "blank whiteness" of a "featureless" plaster cast. "Indeed, so taken was I by the rows of blank white plaster heads [I had seen in the Galton Collection] that it seemed to me that the heads themselves [that is, the heads in her own work] should remain inert, white and anodyne as aspirin". Might this in fact provide us at last with an image of an inviolate self, no longer monstrous or malformed, "half eaten by cancers", or brutally and traumatically disfigured42.

Traditionally, the media used for the preservation of wet specimens (alcohol or formalin, for example) have been intended to function as a neutral environment within which the specimen could exist in a state of as-if suspended animation. Now, however, following this conceptual turn-about, it was to be the liquids in which the heads were immersed that "reference[d the intended] contrast between purity and abjection". Rather than serving the end of preservation, of rendering a biological specimen at least theoretically immutable to change, the liquids in the flasks that contained the plaster casts (milk, wine, urine) were themselves biological agents, both susceptible to change over time and capable of staining or otherwise "defacing" the casts which were partially suspended in them43.

At the same time, this strategy allowed the entire display to be invested with a specifically spiritual resonance. "The cabinet [in which the flasks were displayed] took on a religious aspect [with the fluids reflecting the light like stained glass]44; while the fluids themselves had religious and transformative significances: the blood of Christ, the milk offered to Ganesh, the urine of reindeer imbibed by the shamans of Lapland". In short, the fluids intended to evoke the idea of the in vitro preservation of medical specimens, instead function to stain the immaculate whiteness of the plaster heads, while being themselves subject to organic corruption and decay, even as they suggest the possibility of spiritual transformation, salvation, and regeneration.

There remains, however, the final flask filled with water and containing no cast. Viewer feedback suggests that this "empty" flask was seen as especially disturbing or frightening: the implication being that the cast had dissolved in the clear liquid, and, more terrifying yet, that this dissolution had left no trace, only an invisible absence.

In fact, of course, there had never really been a "presence". The flask of water presents nothing other than itself: a concrete embodiment of the abstract structure of preservation and display. Or, it might equally stand as a metaphor for a world pure and self-contained, untroubled by the insistent feedback of that thing called "self". Conversely, the three flasks containing casts and biological fluids graph a system of circulating relationships between "world" and "self", mutually interconnected as the fluid penetrates the plaster of the cast, seeping in through tiny cracks to dislodge bits and pieces that float and dissolve in the supporting medium. And it is only the presence of these tiny cracks and spaces that allow that interpenetration to take place, despite the apparent inviolability guaranteed by the pristine whiteness of the casts. Only in a world without self, it seems, is there purity and clarity, transparency and integrity with no interstices or troublesome in-betweens.

Indeed, it may be that the images of self we have examined here, all in some way monstrous, fragmented, tormented, pathological, in fact describe a state of things constrained in its possibilities by the fact of our postmodernity, the state of the self as it is - and as it must be, in a world where "pathological as the new normal".

8. Staging the self: object - subject - process

Consider the Hunterian Museum in London. Badly damaged during the Blitz in 1941, the museum and its collections have since undergone several restorations, re-buildings, and reconfigurations, opening in their present form in 200545. The exhibition space is now a transparent environment of glass and light. It appears more like a celebration of the "vitrine culture" of contemporary art installation than an homage to the Renaissance cabinet of medical curiosities or the nineteenth-century medical research collection.

This has in effect created a hybrid space consonant with the museum's expanded mission, as well as a location ideally suited to the staging of the whole range of conceptions under which the collection's material is understood, used, and appropriated. In simplest terms, specimens appear at once as objects and subjects: both as material indices of conditions, diseases, and pathologies; and as the remains of once-living persons who lived, suffered, and died as victims of disease or deformity, each one the subject of a particular history.

It is worth reiterating, first of all, that both of these conceptions have roots deep in the history of medicine itself, involving (in scientific terms) competing models for understanding the definition and aetiology of disease; but related as well to questions surrounding the relationship between doctor and patient, as well as the post-mortem status of deceased patients and other anatomical and pathological "material"46.

At the same time, this subject-object dichotomy is both reflected, and reflected upon, by other users of specimens in the collection. These users are obviously of many types -both "lookers" and "makers", both individuals whose frame of reference is frankly transgressive, and those who approach what they see with interests that might be either artistic or scientific, or neither. It seems most likely, however, that, even for narrowly medical users, both frames of reference and the responses developed within them will be complex, and that the status of the specimens on which they focus will appear (at various times) both as mute and material objects and as narrating once-living subjects.

In any case, artists are certainly free to blur both the line between subject and object, and other more-or-less well defined demarcations, as between normal and pathological or art work and anatomical illustration or exhibit47. The career of Eleanor Crook (where we might look especially at the 2013 multi-media installation And the Band Played On) provides an excellent example of how this works out in practice48. Institutionally more complex, but incorporating essentially the same freedom to move across categories, was the Hunterian's own exhibition War, Art, and Surgery (with accompanying conference and publication) on display from 14 October 2014 to 14 February 201549.

As the line between art object and anatomical specimen becomes blurred within these new hybrid or heterotopical exhibition spaces (whether chapel and asylum or museum and gallery) what impact might there be on an artist's sense of his or her own "self" in relationship to the products of their artistic activity? Obviously there is no easy or single answer to this question, as there was no easy or single answer for the pathological anatomists Hirst and Piersol. The artist, however relentlessly and meticulously descriptive is not simply a mechanical recording or indexing device. The co-ordinated operation of eye and hand always leaves both a descriptive trace and an ideological shadow. And that shadow is in fact a "self" seeing its object of study perhaps as a reflection, perhaps as an "other"; perhaps as an inanimate or dis-animated subject, perhaps only as a thing not even dead, just so much bone or muscle or organ. Indeed, it may well be that the heterogeneity of the situation, the fundamentally different ways of seeing and knowing that this heterogeneity encourages, guarantees an equally heterogeneous image. Perhaps, faced with this insistent conundrum, the artist can only produce a self-image that is fractured or fragmented: a shattered reflection, a dis-animated "other", a being at once subject and object, alive and dead, preparator and specimen -a perfectly self-alienated post-modern self.

But if this image of the postmodern self is thus somehow necessarily fragmented, interstitial by its very nature, perhaps we can grasp a different potential outcome, a different sense of a different kind of "self", by considering that self as process rather than as image.

Rather than seeing the self as if portrayed in the complete image of a pathological specimen, let the self unfold in the act of creating that image.

Rather than striving to attain a sense of some monstrous or ghostly or terrified interiority, feel the essential and external physicality of the specimen in the physical act of tracing that exterior presence. As Temple-Cox relates, "She [the artist] does not feel pity, or empathy, or sorrow for the non-life of the baby in the jar. She connects instead, while drawing, directly with the physical remains: the delicate crackling line of the fissures of that double skull, skittering out of the end of her pencil, meandering across its terrain like the Colorado River seen from a satellite" (figure 5). And, in tracing its flow, she becomes that river, while that meandering, skittering line graphs the trace of a self that moves and makes, restlessly and continuously, both being and becoming, an interior drive that at once records and animates the purely physical remains of another.

Figure 5. Lisa Temple Cox: drawing of the skeleton of a pair

of Cephalothoracopagus twins housed at the Mütter Museum.

References

1. Asma, Stephen T. Stuffed animals and pickled heads: the culture and evolution of natural history museums. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003, p. xiii. [ Links ]

2. Harcourt, Glenn. Andreas Vesalius and the anatomy of antique sculpture. Representations. 1986; 17: 28-61, especially p. 40-42 on the skeletal figures from the Tabulae sex. [ Links ]

3. The Mütter specimen entered the Pathological Cabinet of the College of Physicians in 1851. Worden, Gretchen. Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. New York: Blast Books; 2002, p. 181. [ Links ]

4. The classic study is still Foucault, Michel. The birth of the clinic: an archaeology of medical perception. New York: Vintage; 1975. [ Links ] See also: Maulitz, Russell C. Morbid appearances: the anatomy of pathology in the early nineteenth century. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [ Links ] For a thumbnail summary, succinct and lucid as always, see: Porter, Roy. Blood and guts. A short history of medicine. New York and London: W.W. Norton; 2002, p. 77-78. [ Links ]

5. For a brilliant explication of the intellectual and scientific background, see: Porter, Roy. Flesh in the age of reason. London: Allen Lane; 2003. [ Links ]

6. For a dense but essential philosophical overview of this issue, see: Canguilhem, Georges. The normal and the pathological. Dordrecht: D. Reidel/Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1978, especially chapter "A critical examination of certain concepts", p. 125-149. [ Links ] For the views of the two practising physicians responsible for assembling the classic English language atlas of teratology, see Hirst, Barton Cooke; Piersol, George A. Human monstrosities. Philadelphia: Lea Brothers & Co.; 1891-93. [ Links ] This is a fascinating work, which deserves a significant treatment in its own right. The photographs especially (but also the drawings) force the reader and observer to confront the issue of the ability of imaged monstrosity to disrupt our expectations regarding the form of humanity in the most direct and brutal possible way. We seem at times to be moving through a Boschean portrait gallery, populated by fantastic, demonic creatures, parodies or perversions of human beings. Yet the residue of a genuine, pathetic, brutalized, and suffering humanity is almost always impossible to escape. Nor is this a tangle that the authors themselves, who refer to their specimens at one point as "jewels from a beautiful collection", seem predisposed or even able to avoid. A number of the original photographs used to illustrate Hirst and Piersol are reproduced in Worden, Gretchen. Mütter Museum historic medical photographs. New York: Blast Books; 2007, p. 197-200, 204-205, 208-209. [ Links ] The photographs in: Herzog, Lena. Lost souls. Millbrook, New York: de.MO design Ltd.; 2010 provide a heartbreakingly poignant meditation on this problem. [ Links ] See also Purcell, Rosamund. Special cases. San Francisco: Chronicle Books; 1997, especially chapter "Too much, not enough, and in the wrong place", p. 67-78. [ Links ] Purcell's photo (89) of the skeleton of a hydrocephalic child (Utrecht, Universiteitsmuseum) "whose skull has opened like a flower" endows its bowing subject with an almost impossible formality and dignity.

7. The following discussion is indebted to the lucid and informative overview provided in: Leroi, Armand Marie. Mutants: on genetic variety and the human body. London: Penguin; 2003, especially chapter: "A perfect join: on the invisible geometry of embryos", p. 23-62. [ Links ]

8. Paré, Ambroise. On monsters and marvels. Chicago: Chicago University Press; 1982, p. 14. [ Links ] This is a wonderful little annotated edition by Janis L. Pallister, illustrated with Paré's own woodcuts. The argument given by Paré derives finally from Aristotle. Although Paré is often credulous and his natural history quite fantastic, he was in fact a surgeon with considerable obstetric experience (he revived the practice of podalic version in cases of difficult presentation, for example) and certainly must have known such problematic beings on the basis of first-hand experience, as he himself asserts.

9. Paré, n. 8, p. 8-9. Based on later, more authoritative reports, it is hard to credit this aspect of Lycosthenes' narrative; but the point here is not so much whether the narrative is in detail true or false, but how it attempts to articulate a coherent answer to the question: are we in the presence of one self or two?

10. To flesh out this skeletal narrative, see: Leroi, n. 7, p. 23-27. In this case, dissection revealed that Christina's heart was normal and healthy, whereas that belonging to Ritta was deformed and malfunctional, as if to signal an incomplete or transmogrified "self". For a much more heart-warming, and contemporary, story, see the literature (not all of it exploitative) surrounding the lives of Abigail (Abby) and Brittany Hensel, the dicephalic parapagus twins, born 1990 in Minnesota, and now college graduates. For example: http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-22181528 (accessed 26 May 2014). [ Links ] And, of course, they also have a Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/AbigailAndBrittanyHensel (accessed 26 May 2014). [ Links ]

11. Leroi, n. 7, p. 33.

12. Leroi, n. 7, p. 35. Leroi's discussion also provides actual embryological substance to compliment the metaphor developed above of the simultaneous joining and tearing asunder of conjoined bodies.

13. Leroi, n. 7, p, 27.

14. The use of portrait casts (both life and death masks) can be traced back to the familial and funereal rituals of the Roman Republic, a practice which included their display as if in a gallery in the atria of well-to-do houses.

15. In addition, such masks are not uncommonly found in anatomical collections, although their function there is not usually related to pathology. The use of moulage, or wax models, to simulate the effects of wounds and disease, as well as the collection of wet specimens (and archival photographs) provide an intra-collection context for masks of this sort. Worden, n. 6, provides numerous examples of all these kinds of objects.

16. Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida. New York: Hill and Wang/Noonday; 1981, p. 96. [ Links ]

17. Lisa Temple-Cox, quoted from her presentation, "Making Myself a Monster: Self-Portraiture as Medical Specimen", at the conference Cultures of Anatomical Collections, Leiden University, 15-17 February 2012. [ Links ]

18. Conversely, the traditional employment of such collections as material aids for anatomical and medical teaching and research has declined dramatically in the face of developing technologies that make such hands-on experience seem increasingly irrelevant. We should also bear in mind that, although the circumstances surrounding the imposition of restrictions on access to anatomical collections may be specific to such collections, it is a characteristic of museums in general (as well as archives and other "collecting" institutions), that public access to collections of all kinds is routinely and often quite tightly restricted. For the English medical background, see: Alberti, Samuel. Morbid curiosities: medical museums in nineteenth-century Britain. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2011. [ Links ]

19. Their websites http://www.collegeofphysicians.org/mutter-museum/ and Links ]org/">http://muttermuseum.org/ (accessed 26 May 2014) provide easily accessible portals. [ Links ] See also: Harcourt, Glenn. Terrifying beauty: the public face of the Mütter Museum. Paper delivered at the conference Cultures of Anatomical Collections, Leiden University, 15-17 February 2012 (unpublished). [ Links ]

20. A glance at their Facebook page https://www.facebook.com/BartsPathologyMuseum (accessed 26 May 2014) gives a good idea of the breadth of their offerings. [ Links ]

21. See, for example: http://www.rcseng.ac.uk/museums/hunterian (accessed 26 May 2014) for the Hunterian Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons, [ Links ] England. In addition, Europe as a whole seems to have developed a vibrant culture of interdisciplinary programs and academic initiatives in the medical humanities easily equal to anything that can be found in the U.S.

22. See: http://www.juxtapoz.com/ (accessed 26 May 2014). [ Links ]

23. It should also be noted that the structures, objects, and institutions of natural history have been involved in this explosion as well, to the end that, taken in toto, we seem witness to a deconstruction and reconfiguration of the natural historical and medical sciences encompassing their entire history from the sixteenth to the early twentieth centuries. For a marvellous institution that sits precisely on the high/low or serious/transgressive borderline, see: New York City's Morbid Anatomy Library and Museum: http://morbidanatomy.blogspot.com/p/morbid-anatomy-library.html (accessed 26 May 2014). [ Links ]

24. For these and other related works, see the comprehensive catalogue and illuminating (even when obscure or obtuse) comments at Hirst's own website: http://www.damienhirst.com/home (accessed 26 May 2014). [ Links ]

25. A Google search on "skeleton tattoos", "conjoined twin tattoos", "fetal skeleton tattoos", etc. will yield a selection of more-or-less extreme examples.

26. See Worden, n. 3 and Porter, n. 5 for full publication information on Hirst and Piersol; and references to the examples reproduced in Worden, n. 6.

27. Worden, n. 6, p. 208-209 and n. 3, p. 87 (rear view).

28. The pair of "smiling" and "happy" dicephalus dibracius diauchenos twins (a sweet little "two-headed girl" like Ritta and Christina Parodi) are perhaps more difficult to rationalize in this way. Worden, n. 3, p. 86. Indeed, we can see the earlier book's internal tension starkly presented in the title, where the two words "Human" and "Monstrosities" appear as a grammatical parataxis: presented side-by-side with no immediate indication of which might be "weighted" more or intended to carry the primary signification. Are these human beings, who happen in form to be monstrous? Or are they developmental monstrosities, who happen fortuitously to be, or simply seem or appear to be human?

29. Worden, n. 3, p. 110-111.

30. Harcourt, n. 2.

31. Worden, n. 3, p. 44-45.

32. Unlike the famous and much remarked work of Frederik Ruysch (1638-1731), the "narrative" evoked by Akin and Ludwig is no macabre fairy-tale or whimsical yet moralizing memento mori. Rather, it is dark and forbidding, like a rendezvous of "lost (v)iolent souls" in "death's dream kingdom" (from the poem "The Hollow Men" by T.S. Eliot).

33. In the case of Life Mask 4, where two foetal figures are deployed symmetrically on either side of the face, the act of disfiguration plays out a bit differently. There, the abraded figures (seen back-to-front) do not evoke tattoos so much as old and worn graffiti, marks of an ancient vandalism.

34. Porter, n. 5. For a broader cultural context and a more contemporary time frame, see: Sanders, Barry. Unsuspecting souls: the disappearance of the human being. Berkeley: Counter Point; 2009; [ Links ] Young, Katherine. Presence in the flesh: the body in medicine. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1997. [ Links ]

35. Eleanor Crook has worked both as a fine artist and as an anatomical and pathological sculptor for the Gordon Museum of Pathology (Guy's Hospital, London), the London Science Museum, and the Royal College of Surgeons of England. She is an expert in facial forensic reconstruction and has worked and exhibited internationally across fine arts, medical, and scientific domains. The shape of her career is thus much different from that of, for example, Jan van Rymsdyk, whose illustrations for William Hunter's Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus (1774) are the iconic example of his strictly medical specialization. On the other hand, Crook's career path is one that is today increasingly common. http://www.eleanorcrook.com/ (accessed 26 May 2014). [ Links ]

36. An interesting title, and one that might be taken to imply either that we all and essentially partake of the flesh (that is, as "incarnate" or "embodied" beings) or that we are entirely flesh, carnal but not "incarnate", bodily but not "embodied". For the following analysis and quotes on the exhibition (June-July 2012) see the ACCA (Australian Centre for Contemporary Art) video interview and walk-through: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ffzINEejOs0 (accessed 26 May 2014). [ Links ]

37. De Bruyckere's sculpture and installations in fact provide us with a context that can "open out" our reading of Temple-Cox's work, making us alive to some of its potential "promiscuities". It can also provide a bridge to the work of numerous other artists (Louise Bourgeois and Paul Thek come immediately to mind) whose oeuvres have established a profoundly anti-humanistic image of a fragmented self almost inevitably alienated from a profoundly carnal body increasingly marked by violation and degradation. An exploration of the full ramifications of this development is beyond our scope here.

38. For a general discussion plus exterior and interior illustrations, see: Hopps, Walter. Keinholz, A Retrospective. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art; 1996, p. 132-133. [ Links ] On the work, see: http://archivioditra.altervista.org/ING/arch_KIEN_ospedale.html (accessed 26 May 2014). [ Links ]

39. It was originally conceived and executed as the artist's final MA show, and displayed at the Minories Gallery in Colchester, England. In its original form, the installation occupied a specially constructed room with a closed door and restricted lighting, so that visitors had to choose to enter. And it was divided into two sections. Viewers first entered "the clinic", which contained trolleys, masks, drawings, clay models, as well as various scientific glassware and paraphernalia. They then rounded a corner into a second section -"the altar"- which contained only the cabinet of heads discussed in detail below.

40. The use of the word "archival" here is meant to suggest both a location (the physical space housing an archive of specimens: wet room, dry room, etc.) and a practice (the filing of specimens according to specific and particular systems and taxonomies, for example those developed by Geoffrey Saint-Hilaire), as well as the notion of the archive as an instantiation or externalization of cultural memory, and hence a reservoir of ideas, images, and objects available for appropriation and reconfiguration in the process of cultural production. Leroi, n. 7, p. 46-49, Hirst; Piersol, n. 6

41. As Temple-Cox relates, the impetus here came from a visit to the Galton Collection of plaster casts at University College, London.

42. "Half eaten by cancers" is a reference to wet specimens drawn by the artist in the Museé Dupuytren in Paris.

43. The suspension of the casts to a level just below the nostrils might easily suggest a living presence, evoking the idea of the cast as a creature needing to breathe or in actual danger of drowning. It also references the fact that, even in tightly sealed containers, preparations of this sort tend to lose liquid through evaporation very slowly over an extended period of time; so the level of the liquid provides a kind of pseudo-index of historicity, akin to the character of the photographic print in the triple "portrait" by Akin and Ludwig discussed above.

44. This recalls the kind of feeling that Berlinde de Bruyckere evokes in her description of the ACCA installation, We Are All Flesh. In this case, the cabinet functions as a kind of medical or museological reliquary.

45. Alberti, Sam. The organic museum: the Hunterian and other collections at the Royal College of Surgeons of England. In: Alberti, Sam; Hallam, Elizabeth, eds. Medical Museums. Past, present, future. London: RCSE; 2013, p. 16-29. [ Links ]

46. This is a deeply imbricated set of problems and relationships with an immense bibliography to which we cannot hope to do justice here.

47. For an excellent example, see the exhibition: Fabrica Vitae, organized in conjunction with the Vesalius Continuum conference and celebration of the quincentenary of the birth of Andreas Vesalius, held at Zakynthos, Greece, 4-7 September, 2014. http://www.fabrica-vitae.com/ (accessed 2 October 2014). [ Links ] See also n. 34.

48. And the Band Played On (2013) comprises a set of five life-size figures illustrating both the traumatic injuries of modern warfare and early advances in reconstructive surgery. It has been shown at the Dr Guislain Museum (a former lunatic asylum) in Ghent, Belgium (2013) and at London's Florence Nightingale Museum (2014).

49. Alberti, Sam. War, art and surgery: the work of Henry Tonks & Julia Midgley. London: RCSE; 2014. [ Links ]

Fecha de recepción: 29 de mayo de 2014

Fecha de aceptación: 10 de julio de 2015