INTRODUCTION

Infant growth during the first months of life is a sensitive indicator of early health status. Optimal nutrition during childhood provides adequate support for immediate growth and development as well as long-term health. Intrauterine environment, infant feeding practices, family lifestyle habits and socio-cultural characteristics are the main environmental determinants of postnatal growth, as well as predictive variables of later adiposity and metabolic risk 1 2 3 4.

At the present moment in most countries, migration is a key factor influencing nutritional, health, social and growth determinants 5,6. In the last decade, Spanish population has considerably increased mainly due to the migration phenomenon. Spain is nowadays the second country in Europe regarding foreign population amounts. Immigrants reach 5.7 millions in our country, being more than 12% of the total population. This social change, among other aspects, has induced the increase of our national birth rates, being 17.4% of them children with migrant background in the year 2011 when this study was conducted 7.

It is a well-accepted phenomenon that recent immigrants are on average even healthier than the native-born population which is known as "The Healthy Migrant Effect". It has been reported that newborns of immigrant mother have higher birth-weight, lower risk to be born small for gestational age (SGA), and higher rates of breastfeeding maintenance than newborns of Spanish mother 8,9. However, there is no enough information about how migration may influence nutritional status and obesity risk later in life, as it has been observed in other countries 10 11 12.

Several growth standards can be used for evaluating growth and adiposity patterns in Spanish infants: a) World Health Organization (WHO) standards 13, performed from longitudinal study data of 1.737 children born in Brazil, Ghana, India, Norway, Oman and the United States during 1997-2000 and fed with exclusive breastfeeding; b) Euro-Growth standards 14, performed from an European longitudinal study on 2.245 children born in Spain, Austria, Germany, France, Greece, United Kingdom, Hungary, Italy, Ireland, Croatia, Portugal and Sweden during 1990-1996; and c) Spanish Growth Study 2010 15, from a cross-sectional study on 38.461 children born in five different Spanish regions from 2000 to 2010. It has been reported differences in growth and adiposity infant patterns depending on the growth standard used 16,17. In addition, some of them are not designed for a mixed population of native and migrant background children. Therefore, the aim of this study is to compare growth and adiposity patterns from birth to 24 months of age in Spanish infants, depending on maternal origin and considering the previously mentioned growth standards.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

GENERAL DESIGN AND STUDY POPULATION

Participant population belonged to the CALINA Study (Spanish acronym of Growth and Feeding in Infants from Aragón, Spain) 18, a longitudinal study in a representative cohort of infants from Aragón (Spain), from birth to 24 months of age.

The main objective of the CALINA study was to assess growth patterns, body composition and feeding aspects in this population, as well as, to examine prenatal, postnatal and socio-cultural factors which may influence them. It was developed in a random sample of Primary Care Centers of Aragón, meeting the following inclusion criteria: to have permanent trained pediatric staff conducting the Spanish Child Health Program at least in the last 2 years and with compliance and attendance over 80% of the population living in this area. Infants included in this study were those born between March 2009 and February 2010 (both inclusive), whose parents signed the written consent at the first scheduled health examination in the selected centers. Infants with malformations, diseases, physical disabilities or other important conditions which could affect growth or nutritional status were excluded. The sample initially recruited (1.602 newborns) was representative of the population born over this period in Aragón 18. For the present analysis we only included infants born at term (gestational age ≥ 37 weeks) (n = 1,430). They were divided into 2 groups according to maternal origin: Immigrant group: infants born to immigrant mothers (n = 331) and Spanish group: infants born to Spanish mothers (n = 1,099). The study was performed following the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki 1961 (revision of Edinburgh 2000), the Good Clinical Practice, and the legislation about clinical research in humans and was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Aragón (CEICA).

VARIABLES AND MEASUREMENTS

Birth weight and length were obtained from hospital records. Anthropometric measurements were registered by the pediatric trained staff at the Primary Care Centers selected at 3, 6, 9, 12, 18 and 24 months of age following standard protocols 18.

Body weight was measured in kilograms (kg) with an infant scale (sensitivity of 10 g); length was measured in meters (m) with a homologated measuring telescopic board for this use (sensitivity of 1 millimeters); body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight by the squared length (kg/m2); triceps and subscapular skinfolds thickness measurements were assessed at the left body size with a Holtain(r) skinfold Caliper (sensitivity of 0.1 mm).

Parents completed a questionnaire about maternal origin and women born outside Spain were considered to be immigrants.

Data analyses were performed with IBM Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS), version 19.0 (IMB Corp., New York, USA, 2010). Data normality was verified using the Kolgomorov-Smirnov test and the residue variance homogeneity was verified using the Levene test. Anthropometric measurements were converted into z-scores using Euro-Growth 14 and Spanish Growth Study 2010 15 standards for each age and sex as follows:

z-score = measured value - mean population / standard deviation

WHO growth standard 13 z-scores were calculated using WHO growth macros for SPSS Syntax File for PC 19. Z-score values ≤ 4 or ≥ 4 were considered implausible and excluded. Infants at risk of overweight, overweight and obesity at 24 months of life were defined as +1, +2 and +3 BMI z-scores, respectively 13,20. Mean z-scores differences between both groups (immigrant vs. Spanish maternal origin) where examined by student´s t-test, and mean z-scores calculated using the three different growth population standards by analysis of variance (ANOVA). A significance level of p < 0.05 was adopted.

RESULTS

Mean weight, length, BMI and skinfold z-scores of the sample, calculated by the selected growth standards and stratified by maternal origin, are shown in table I and table II. Mean infant z-scores significantly vary depending on growth standards used.

Table I Mean infant z-scores for weight, length, body mass index and skinfolds z-score up to 2 years of age in Spanish maternal origin group

BMI: body mass index; CI: confidence interval; WHO: World Health Organization; z-score: Standard deviation score. *p-value from ANOVA between mean infant z-scores calculated by different growth standards for the same anthropometric measure.

Table II Mean infant z-scores for weight, length, body mass index and skinfolds z-score up to 2 years of age in immigrant maternal origin group

BMI: body mass index; CI: confidence interval; WHO: World Health Organization; z-score: standard deviation score. *p-value from ANOVA between mean infant z-scores calculated by different growth standards for the same anthropometric measure. **p-value from t-student between mean infant z-scores of Spanish maternal origin group vs. immigrant maternal origin group for the same anthropometric measure (ap <0.001; bp <0.01, cp <0.05, ns: non significant).

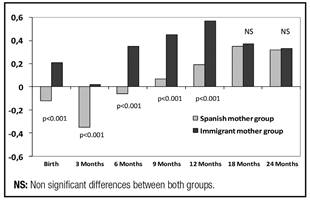

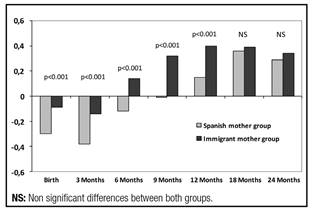

According to WHO standards, mean weight, length and BMI z-scores were higher in immigrant group up to 12 months (p < 0.001). Differences decreased progressively and at 18 and 24 months they were not significant (Fig. 1, Fig. 2 y Fig. 3). Mean Z-score for triceps skinfold only showed statistical differences at 3 months with higher values in immigrant group (p < 0.05) (WHO standards) (Fig. 4). Mean Z-score for subscapular skinfold were significantly higher in immigrant group from 3 months to 18 months, while non-significant differences were found at 24 months of age (WHO standards) (Fig. 5). We did not observe statistically significant difference in the prevalence of infants at risk of overweight and overweight at 24 months of age between Spanish (15.1% and 3.8%, respectively) and immigrant group (14.7% and 4.9%, respectively) when using WHO standards. Nevertheless, differences between both groups remained using Spanish and European standards during the studied period. We did not found obese infants in either group (Table I and Table II).

Figure 1 Mean infant z-scores for weight up to 2 years of age depending on maternal origin by World Health Organization growth standards.

Figure 2 Mean infant z-scores for length up to 2 years of age depending on maternal origin by World Health Organization growth standards.

Figure 3 Mean infant z-scores for BMI up to 2 years of age depending on maternal origin by World Health Organization growth standards.

Figure 4 Mean infant z-scores for triceps skinfold up to 2 years of age depending on maternal origin by world Health Organization growth standards.

Figure 5 Mean infant z-scores for subescapular skinfold up to 2 years of age depending on maternal origin by world Health Organization growth standards.

Mean weight z-score values of Spanish group were all negative except for those calculated using the WHO standards that became positive from 9 to 24 months of age. In contrast, weight z-scores in immigrant group were always positive at all ages independently of the growth standard used (non significant differences at 6 and 24 months) (Table I and Table II). Length z-scores were weak positive in Spanish group except for those from Euro-growth standards. Length z-scores were always positive in immigrant group, although decreased progressively up to 24 months of age. BMI Z-scores of Spanish group are negative except for those from WHO standards, that became positive from 12 months. Immigrant group showed negative BMI Z-scores from 9 to 24 months compared to Spanish and Euro-growth standards but they have positive Z-scores compared to WHO growth standards from 6 to 24 months (Table I and Table II). Mean triceps and subscapular skinfold z-scores substantially and progressively increased from 3 months (negative Z-score) to 24 months of age in both groups compared to WHO standards (Table I and Table II).

DISCUSSION

Spanish population has undergone an important demographic change in the last decade due to immigration. According to the published data by the Statistical Office of the European Communities (EUROSTAT) 21, immigrant population increased considerably in our country from 923,879 in 2000 to 5,730,667 in 2011. Foreign population living in Spain comes mainly from Africa (both Maghreb and Sub-Saharan countries), Latin-America and East Europe. This social change has influenced the increase of Spanish birth rates, being the 17.4% children with migrant background in the year 2011 7. The anthropometric data in our study were obtained longitudinally in a large and representative sample of the population born over this period in Aragón (North of Spain) 18, showing even higher percentage (23.1%) compared with national data but similar to official immigration rate in Aragón (20,4%) and other bordering areas 7. The obtained results could be extrapolated to the rest of Spain and to countries with similar demographic characteristics.

It is well known that immigrant mothers in our country are younger, have lower educational level, greater parity, longer duration of breastfeeding, less smoking consumption rates and higher weight gain during pregnancy 23 24 25 26. Many of these factors and other perinatal and nutritional characteristics make that their infants had lower risk to be born small for gestational age (9.2% in Spanish origin mothers vs. 3.8% in immigrant origin mothers), less morbidity and higher birth anthropometric measurements 27 28 29.

Spanish newborn anthropometric characteristics depending on maternal origin have been already described 23,30, however, there is no enough information about how migration may influence infant nutritional status, growth patterns and obesity risk later in life in our country. Carrascosa et al. 31 published cross-sectional studies conducted on populations from African (The Maghreb and Sub-Saharan regions) and South American (Inca and Mayan regions) origin infants born in Spain. Both populations were separately assessed, and showed similar values to those found in the native Caucasian population during the first years of postnatal life 31. CALINA study reported data on postnatal infant growth characteristics in children born to immigrant mother in our country and compared growth patterns from birth to 24 months of life between infants born to Spanish and immigrant origin mother. Differences in infant growth and adiposity patterns depending on anthropometric standard used, has also been showed. Results showed that weight, length and BMI z-scores were higher in immigrant background group up to 12 months, but at 18 and 24 months there were not significant differences according to WHO growth standards 13. However, differences between both groups remained in our sample when using European and Spanish growth standards 15.

New immigrants in developed countries have significant health advantages that contribute to facilitate an adequate perinatal health status and good postnatal growth, either comparable or even better than native-born population conditions, according to some studies published in other countries 24.

In spite of the Healthy Migrant Effect theory, socio-cultural characteristics of this population group give an explanation for the loss of health advantages over the time in the host country 10,32,33. A process of acculturation may cause that immigrants gradually adopt habits and lifestyles of the country where they live. Sedentary patterns, dietary habits or consumption of tobacco and alcohol those are deleterious to maintain health status 11. For example, in a study conducted in Canada, the probability of being overweight in adult immigrants on arrival was lower than in comparable native-born Canadians, but increased gradually with additional years in their new country and met or exceeded native-born levels after approximately 20-30 years 10. Similar patterns for adult immigrants have been observed in UK or in the United States of America (USA) 11,12.

This increased risk of overweight has been widely described also in children born to migrant population and in their following generations in USA 33; as well as more recently, in European countries (UK, Sweden or Netherlands) 32,34 35 36 and Australia 37. In Spain, there is still no conclusive data about family migration and risk of adiposity in their descendants. In our sample, using the WHO growth standards 13, neither the prevalence of overweight nor subcutaneous adiposity measures showed statistical significant differences at 24 months of age depending on maternal origin. However, we observed higher subcutaneous adiposity levels in both groups, so skinfolds z-scores substantially and progressively increased from 3 months to 24 months of age compared to WHO standards. Perhaps this fact depends on WHO sample that was selected from exclusive breastfed infants (for at least 4 months) in emergent countries where the availability of food and nutritional status could be different. Prospective study of a Spanish cohort will be necessary to describe growth patterns and to assess obesity development and body composition differences depending on migrant background later in life.

We have previously reported that wide differences in the assessment of infant growth and nutritional status can be found depending on the growth standard used in the same population 16,17. It might be the case that a child met criteria to be considered at nutritional risk with one growth standard, but not with others 16. The characteristics of the population selected and the methodology applied to perform growth standards could explain differences among them. This fact has been demonstrated in our study sample by calculating z-scores for several anthropometric variables using WHO 13, Euro-Growth 14 and national (Spanish Growth Study 2010) growth standards 15. Mean infant z-scores significantly vary depending on growth standards used, so differences between Spanish and immigrant maternal origin groups remained using Spanish and European standards. WHO growth standards have been elaborated in a normative cohort of children from 7 countries with optimal environmental and nutritional conditions; meanwhile, Spanish and European growth standards are from observational studies, showing the current trend of infant nutritional status, higher values of BMI and an overestimation of undernutrition. So there are differences in BMI at 24 months but no in height. This is important because healthy children in low percentiles from WHO growth standards should be under the third percentile in the others, and they might be classified as malnourished causing unnecessary nutritional support.

In addition, considering socio-cultural and demographic changes produced by immigration, it seems recommendable to periodically review the growth standards. Cross-sectional and longitudinal growth studies conducted on the native Caucasian population and growth data of the immigrant population are currently available in Spain 30,31.

In conclusion, infant growth and adiposity patterns depending on maternal origin showed initial differences but they progressively disappear at 24 months of life. At birth, immigrant maternal origin infants have higher weight, length, body mass index and triceps and subscapular skinfolds than Spanish maternal origin infants. After 18 months of age, anthropometric differences between both groups disappear when WHO 13 standards are used. At 24 months, the prevalence of overweight is similar in both groups. Further studies are needed to confirm or refute these findings as well as to assess long-term effects of immigrant background.