INTRODUCTION

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a functional, diffuse, widespread pain-syndrome classified and recognized by the World Health Organization as a rheumatic pathology with unknown aetiology and currently with no specific effective pharmacotherapy 1. Globally, FM is the third most frequent rheumatic disease, presenting a prevalence of 3.7%, in Portugal 2 and an average age of affliction of 59 years old 3.

FM is a chronic disease having strong impact on the quality of life and, similarly to the majority of chronic diseases, there is a substantial relationship between nutrition, health and well-being 4. Current guidelines consistently recommend a multidisciplinary approach for treating FM 5, wherein nutrition could play a key role.

In addition, obesity is a common factor in patients presenting FM 6. However, it is difficult to determine if obesity associated with FM is a consequence of inactivity imposed by pain, mental state, medication or other factors, or inversely, if obesity directly contributes to FM as an physiopathological aspect. Several studies found that being overweight can affect symptoms of FM 6. Arranz et al. showed a specific body composition in FM patients (high fat mass and low fat free mass) and found that BMI and body composition were correlated with quality of life and symptoms in FM patients 7.

Fava et al. described an increased metabolic risk, with insulin resistance, in FM patients probably due to a relationship between BMI and C-reactive protein, reflecting a micro-inflammation environment, especially in obese FM patients 8. In another study, Alcocer-Gómez et al. showed, in vitro, that restricting caloric content to patients fibroblasts, resulted in improved AMP phosphorylation, mitochondrial function and stress response, suggesting diet might have an in vivo role in FM treatment 9.

Food sensitivities are also frequently reported by FM patients, indicating a potential dietary link to central sensitization 10. A food awareness survey showed that 30% of FM patients attempted to control symptoms by restricting particular foods 11. Slim et al. proposed dietary interventions for FM treatment using a restricted gluten, lactose or FODMAPs diet; recently, published the results of the pilot trial comparing a gluten free diet (GFD) with a hypocaloric diet (HCD) in FM patients with gluten sensitivity symptoms (NCGS) 12) (13; showed no significant difference between the two interventions but with similar benefits in the outcomes. Despite its specificity, GFD wasn't superior to HCD, including the effects in NCGS 14.This study is in accordance with the opinion of other authors as Biesiekiersk: gluten restriction has no effect in patients with non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS), and suggested that "wheat FODMAP" could be the trigger of FM symptoms, instead of gluten 15.

As a whole, the above results suggest that diet can have a potential therapeutic role in the balance of FM syndrome. One possible dietary approach could be to restrict FODMAPs (Fermentable Oligo-Di-Mono-saccharides And Polyols) as part of a multidisciplinary treatment of FM 16. FODMAPs are composed by, poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates, including excess free fructose, lactose, polyols, fructo-oligosaccharides, and galacto-oligosaccharides 17. A low FODMAP diet (LFD) was already found to alleviate GI disorders and symptoms of IBS 16) (18 and by comparison, as about 70% of FM patients report IBS symptoms 19, we hypothesized that LFDs may have some therapeutic benefit on FM symptoms.

It's based in the evidence that, patients with IBS could present extraintestinal symptoms (2/3 prevalence of rheumatic disease). Symptoms of IBS usually overlap in 70% of FM patients and 60% inversely. Clinically FM does not differ whether or not it has associated IBS symptoms 19) (20) (22.

Literature suggests a possible common cause, responsible by both conditions. Common characteristics between IBS and FM: both are characterized by functional pain, not explained by biochemical or structural abnormalities, with predominance in females, associating with life-stressing and complain of sleep disturbances and fatigue. Therapeutic response to the same pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy is described.

Some authors consider contradictory the association between IBS and FM relating it with anti-inflammatory drugs or possible diagnosis of celiac disease in a history of FM.

To date weren't found studies showing the impact of results of LFDs on FM symptoms. This study was a pilot clinical trial on LFDs impact on FM symptoms and nutritional status of participants. Also, was included the objective of demonstrate the nutritional balance of the LFDs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PARTICIPANTS

A longitudinal study, involving introduction of LFDs to participants suffering from FM. All participants were referred from a qualified rheumatologist having a confirmed diagnosis of FM, according to American College of Rheumatology criteria, 2011 22. The trial was conducted between January and May 2015, based on a four-week, repeated assessment model.

All patients signed an Informed consent agreement (2013 Declaration of Helsinki) to participate in the trial. The research project was approved by the Ethics Committee, Medical Academic Centre of Lisbon.

Inclusion criteria for participants were: 18-70 years old; diagnosed with FM at least one year; having received FM therapy for at least 3 months prior to the study enrollment; and having already excluded referrals on a restricted FODMAP diet, or having comorbidities requiring specific nutritional therapy. Exclusion criteria included the co-morbidities requiring specific nutritional approaches such as renal insufficiency, diabetes, celiac disease. Participants with intercurrences as Influenza and respiratory infections were excluded.

STUDY PROTOCOL

The study consisted in three different assessments "Moments" of four weeks each, at repeated intervals, completing eight weeks of intervention. A physician and a registered dietician were present at all assessments and available throughout the trial.

At the beginning (Moment 0) participants were introduced to the purpose and protocol of the trial. They signed informed consent agreements and received a booklet containing instructions and recipes for preparing food, as well as tables with the food rich in FODMAPs and a record-keeping section for cataloguing foods and food amounts consumed over a 72 h period.

The recommended diet in Moment 1 (M1) was elaborated reducing lactose, replacing it by lactose free products and dairy alternative drinks; reducing excess of fructose replacing apple, mango, peaches, pear, watermelon, honey, sweeteners as fructose, HFCS, by banana, blueberry, grape, melon, orange, strawberry; reducing fructans rich foods as wheat, rye, onion, garlic replacing them by corn, spelt, rice, oat, gluten free products and garlic-infused oil; reducing galactans rich foods as cabbage, chickpeas, beans, lentils replacing them by vegetables as carrot, celery, green beans, lettuce, pumpkin, potato, tomato; reducing polyols rich foods as apricots, cherries, nectarine, plums, cauliflower, sorbitol xilitol replacing them by fruits as grapefruit, kiwifruit, lemon, lime, passionfruit.

Total FODMAP intake [collective amounts of lactose, fructans, galactans, free fructose and polyols (g/day)], energy (kcal/day), and macronutrients/micronutrients consumed by the participants were quantified for each monitoring period (Moment). Participants reported individual food intake based on standardized dish, cup, and spoon measurements. The estimated dietary intake was calculated from these measurements. Quantities were based upon published amounts of FODMAPs and respective food composition tables 23) (24.

At Moment 1 (M1), a clinical/dietary anamnesis was performed to obtain biographic and demographic data, comorbidities, medication requirements, food allergies or intolerances. Anthropometric assessments [weight, body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference (WC)] were performed. OMRON equipment (HBF-511B-E/HBF-511T-E) was used to evaluate fat mass and fat free mass.

All participants completed the questionnaires, which included:

- Fibromyalgia Severity Questionnaire (FSQ), validated according to the new ACR criteria, using a "widespread pain index" (19 points) and a "severity score index" (12 points), wherein combined scores ≥ 13 (0-31) indicate positive criteria of FM 22.

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome-Symptom Severity Scale (IBS-SSS)- uses a five visual analogue scale to quantify abdominal pain, abdominal distension, intestinal transit and the interference of IBS in daily life (0-500), score-ranked as "mild disease" (75-175), "moderate disease" (175-300) and "serious illness" (> 300) 25.

- Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation-Outcome Measure (Core-OM) assessed the mental state and is scored 0-4 26.

- Visual Analogic System (VAS) was applied for calibrating individual symptoms.

All assessment tolls are validated in English language; FSQ, Core-OM and VAS in Portuguese language. Each participant received a personal dietary plan (DP) for restricting foods rich in accordance to FODMAPs. The delivery of the DP was accompanied with accurate instructions and a request for utmost cooperation and compliance. Investigators and participants were totally available to communicate by phone or email in a regular basis.

At Moment 2 (M2) clinical/nutritional data were collected and all questionnaires were filled in, as at Moment 1. In addition, participants completed a questionnaire concerning their satisfaction and adherence to their diet. This questionnaire included questions about overall satisfaction with the study and specific satisfaction with symptoms improvement. Instructions were then given for gradual reintroduction of FODMAPs into their assigned dietary plan (DP). Was chosen a food, representing each FODMAP group, to be reintroduce, increasing the doses along 3 days with a three-day washout period.

Moment 3 (M3) was dedicated to determine any effects resulting from reintroduction of FODMAPs. Clinical and nutritional evaluations were made and assessment questionnaires applied in Moments 1 and 2 were filled in. Lastly, final dietary advice was provided to participants, encouraging them to maintain a balanced diet adjusted to body weight, and to exclude FODMAPs individually identified as being triggers of any negative symptoms.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test, with Lillifors correction, was initially used to assess data normality. Changes in values between Moments were tested using analyses of variance (ANOVA) for repeated measures or the non-parametric Friedman test, if data were evaluated as not normally distributed. For the correlations analyses Pearson test or Spearman test were used. All analyses were performed using SPSS (version 22.0; SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and the significance level was set at p ≤ 0.01 for all tests.

RESULTS

NUTRITIONAL STATUS OF PARTICIPANTS

The cohort consisted of 38 female participants with an average age of 51 years old, and 10 years of diagnosed FM. Thirty-one participants (82%) completed all trial phases. Four types of comorbidities were identified among participants, including gastrointestinal (GI) disorders as diarrhoea, constipation, gastritis, being most common (n = 33; 88%), osteoarthritic disorders (n = 28; 74%), immuno-allergies (n = 23; 60%) and endocrine disorders, such as thyroid dysfunction (n = 7; 18%). 60% of participants (n = 23) reported some form of food intolerance and 11% (n = 4) were allergic to certain foods (documented).

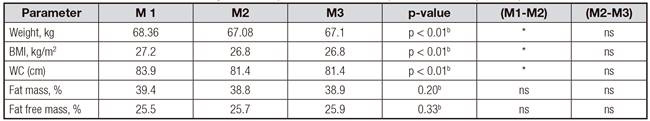

At the outset of the trial, the cohort presented a mean weight of 69 ± 12 kg, BMI of 27.4 ± 4.6 kg/m2, body composition with excess fat mass (39.4 ± 7%) and a fat free mass in the lower limit (25.5 ± 3%), with an average WC of 84 ± 9 cm. Accordingly, a total of 27/38 (71%) of participants had excess of weight, 14 (37%) of them classified as obese. Only 11/38 (29%) were normal weight (Table I).

Table I Participant body composition (n = 38)

*Value expressed as MEAN ± SD; **Expressed as a percentage value.

There was a significant decline in certain anthropomorphic indices among participants between M1 and M2 (restricting FODMAPs). There were significant reductions in mean Weight (> -1 kg; p < 0.01), BMI (-0.4 kg/m2; p < 0.01) and WC (-2.5 cm; p < 0.01). However, no significant changes occurred with body composition (fat mass and fat free mass). The assessment made after reintroduction of FODMAPs, showed no significant changes (between M2 and M3) in all the parameters studied (Table II). Reduction in WC occurred simultaneously with a large reduction in abdominal distension with significant decline (VAS bloating score: M1 = 6.9, M2 = 2.8; M3 = 3.8; p < 0.01) (Table III).

Table II Comparison of repeated assessment of nutritional status between different assessment periods (M1, M2 and M3) of the trial (n = 31)

FODMAP: low fermentable oligo-, di-, mono-saccharides and polyols); BMI: body mass index; WC: waist circumference; *Significant. ap-value of Friedman test. bp-value of analysis of variance (ANOVA)

DIETS

During all assessment moments, diet was characterized according to macro- and micronutrients including FODMAPs intakes, with the objective to demonstrate the nutritional balance of the LFDs. Average FODMAP intake declined significantly between M1 and M2, when was followed the FODMAP restrictive period (M1 = 24.4 ± 12 g/day vs. M2 = 2.63 ± 5.4 g/day; p < 0.01). However there was no significant change in FODMAP intake between M2 and M3, after reintroduction of FODMAPs (M2-M3 = 3.5 g/day; p > 0.05). The amounts of FODMAPs consumed by participants at M2, compared with those calculated in assigned dietary plans (DP), did not differ significantly (M2 = 2.63 ± 5.4 vs. DP = 0.96 ± 1.14 g/day; p = 0.836) (Table IV). Reported compliance in following the assigned diet plans was 86%.

Mean daily energy need was 1,548 ± 121 kcal based on a normocaloric diet for adjusted weight. Introduction of a normocaloric-LFD (1,552 ± 119) to participants resulted in significant (p < 0.01) reduction of caloric intake between M1 and M2 (M1 = 1,958 ± 404 kcal/day vs. M2 = 1,625 ± 304 kcal/day, respectively). In this group of patients, there were no significant differences in micronutrient intake as calcium (Ca), magnesium (Mg) and vitamin D (Vit D) between M1, M2 and M3; although the intakes were always lower according the DRI in all assessments [M1 doses: Ca = 703 mg (daily intake recommendation -DRI = 1000 mg), Mg = 249 (DRI = 400 mg), and Vit D = 2,16 ug (DRI = 15 ug)]. About macronutrients, only was found significant changes in the glycosides consume, between M1 and M2 (233.7 g vs. 180 g; p < 0, 01), and of the lipids, between M1 and M3 (79.4 g vs. 57.8; p < 0, 01). Fiber and protein intake was not affected by changes in the diets (Table IV).

Table IV Comparisons of nutritional intake between different assessment periods (M1, M2 and M3) of the trial (n = 31) and between LFD and DP

DP: dietary plan; LFD: low FODMAP diet. *Statistically significant difference between M1 and M2 (p < 0.01). ¥Statistically significant difference between M1 and M3 ONLY (p < 0.01). ap-value of Friedman test. bp-value of analysis of variance (ANOVA).

SYMPTOMS

According to the IBS-SSS classification, this cohort presented only 2/38 (4%) of the participants with a score below 75 (without disease), and 33/38 (87%) classified as moderate to severe disease (score over 175); 25/36 of them (70%) presenting the sub-type constipated (IBS-C) (Table V).

Table V Characterization of gastrointestinal symptoms of FM among participants prior to initiation of the trial

aExpressed as mean ± SD. IBS-SSS: Irritable Bowel Syndrome symptom severity scale; IBS with constipation (IBS-C), with diarrhoea (IBS-D) and mist (IBS-M).

After introduction of LFDs, there were significant reductions in GI symptoms. The average improvement in IBS-SSS score was 132 ± 117, representing a significant 50% reduction after 4 weeks of LFDs (M1 = 275.3 vs. M2 = 137.4; p < 0.01) (Table III). The symptoms of Abdominal Pain and Distension also showed significant reductions after introduction of LFDs, between M1 and M2 (M1 = 5.0 vs. M2 = 2.4 and M1 = 6.9 vs. M2 = 2.8; p < 0.01; in pain and distension, respectively) (Table III). But, these declines were no longer significant after reintroduction of FODMAPS. There was also a significant reduction in constipation with LFDs during M1 and M2, and a non-significant increasing after reintroduction of FODMAP, as assessed at M3 (M1 = 5.7, M2 = 3.3, M3 = 3.8; p < 0.05) (Table III).

There were significant declines (patient improvement) in all individual FM symptoms between M1 and M2, especially with scores on somatic pain (VAS) (M1 = 6.6, M2 = 4.9; p < 0.01) and muscle tension (M1 = 6.1, M2 = 4.9; p < 0.01) in accordance with the reduction in severity of FM (M1 = 22; M2 = 17; p < 0.01). No significant differences were noted after reintroduction of FODMAPs. The distress score throughout the trial and was not aggravated by reintroduction of FODMAPs (M1 = 1.8; M2 = 1.6; M3 = 1.5) (Table III).

It was found notable, positive correlations between improvements of somatic pain (declined VAS scores) with a number of GI symptoms, including abdominal pain (rs = 0.443; p < 0.01), abdominal distension (rs = 0.386; p < 0.05) and with the improvement of IBS-SSS score (rs = 0.406; p < 0.01). Of particular note was "rate of satisfaction with improvement in symptoms" being strongly correlated (r = 0.650; p <0.01) with "diet compliance rate", suggesting patients were conscious of LFDs lowering severity of symptoms. In concordance, was reported 77% of satisfaction with the diet in general and was observed 85% of compliance to diet plans.

DISCUSSION

This was the first clinical trial wherein a LFD intervention was experimented as a potential therapeutic approach for FM. The results of this pilot intervention with LFD, suggest beneficial influence on the outcome of somatic and visceral symptoms of FM 27. The study could prove that, the dietary plan implemented restricted in FODMAPs, was nutritionally balanced and provided a healthy diet, with benefits on weight status, at least for the period of the duration of the trial (4-8 week). Was found a very significative compliance to the assigned diets, comparing the participants FODMAPs intake with DP content.

There are some concerns regarding safety and nutritional balance of LFDs 28. LFDs prescribed in our study were helpful in providing a balanced intake of energy, macro- and micronutrients.

Our cohort exhibited nutritional status profiles similar to previous studies describing FM body composition 6 with a high prevalence of overweightness and high fat mass 29) (30. The majority of research already done on FM, presents the weight loss as being crucial on alleviating its impact 7) (31. We found a nutritional benefit provided by the prescribed LFDs, resulting in weight-loss without significant decrease in essential nutrient intake (protein, fiber, calcium, magnesium, vitamin D. The nutritional counselling promoted a tendency to improve the intake of important nutrients as calcium and vitamin D without, however, to be sufficient to achieve the recommended levels for the needs of these patients. The micronutrient intake was generally low in all assessed moments, which agrees with the data of publications describing the same pattern of nutritional deficiencies in FM 32) (33.

The results of this trial have notable commonalities with other study's, where was implemented a LFD therapy for IBS treatment 16) (18) (28. LFD was found to alleviate symptoms of IBS in all published studies, providing an improvement of 75% in IBS cases. In IBS, LFD was found to be especially effective in relieving abdominal pain and distension, but was less effective in mitigating constipation 16) (28. Also, we found this response among our cohort of FM patients, with alleviation of GI symptoms by LFD therapy and the most prominent response in abdominal pain and distension. These results reflect those published by Perez et al. where 31 IBS patients were treated with LFD for 21 days (34). Additional comparison between ours and Perez et al. results, shows reductions in VAS abdominal pain scores (6 to 2.8 vs. 5 to 2.4, respectively) and VAS distension scores (7.0 to 4.2 vs. 6.9 to 2.2, respectively).

The results of the intervention in the subgroup of FM constipated patients, are consistent with the Rao et al. opinion (28), about IBS patients treated with LFD. The study also found reduction in the global IBS score in IBS-C sub-type, when treatment of LFD was implemented. Thus, LFD can to be a potential therapy in FM patients suffering from constipation but, such therapy, needs to be accompanied by educating patients to strictly adhere to recommended levels of dietary fiber and water intake. Other studies report a large predominance of constipation (IBS-C sub-type 90%) in patients with FM 19)(34. Our trial showed a 70% prevalence of constipation (25/36, IBS-C), 8% with diarrhoea (3/36, IBS-D) and 22% with mixed symptoms of diarrhoea and constipation (8/36, IBS-M). The prevalence of IBS-C in FM sufferers appears to be higher than in patients with only IBS, in general, where it is reported to be about 50% of cases 35. Another study of LFD therapy for IBS showed this same profile: 64.5% IBS-C, 22.6% IBS-D and 12.9% IBS-M 32. Authors 28 discuss the possibility that the reduced fiber intake of the LFD may contribute to constipation aggravation. Regarding the data from our study, we found that fiber intake was not significantly different throughout the trial and fiber consumption was always sufficient in relation to the daily needs in this trial. Based on these observations, we concluded fiber content did not contribute to any changes in FM symptoms in our study.

It should be noted that the reduction of prebiotic fiber, resulted from the fructo-oligosaccharide LFD restriction, is described as a possible risk factor to colon health and can contribute to constipation and colorectal cancer 28) (36. However, these risks appear to be contradictory to the evident improvement of IBS symptomatology treated with LFD, as described by authors 16 and confirmed in our study with FM patients suffering from concomitant IBS. This contradiction has been described by authors as the "paradox of the LFD" 3. Furthermore, the eventual risk of lowering prebiotic fiber content could be avoided by concomitant inclusion of probiotics in LFD therapy. This hypothesis has already been proposed 16 but has yet to undergo study.

The more remarkable results of our study were the alleviation of FM symptoms as somatic pain, muscle tension and impact in the daily life of FM, after treatment with LFDs. Moreover, gradual improvement of distress score, throughout our study, was an added contribution of LFD therapy to symptomatic improvements. The positive correlation between reductions in somatic pain and GI disorders, in our study, is also notable. More extensive research is needed to discern the interconnection between these symptoms in FM patients.

There are many other aspects of LFD therapy open to future research. One is determining what role, if any, LFD-therapy plays in the neuro-enteric axis of FM patients. Also, cost/benefit analysis of implementing LFD-therapy for treating FM needs to be investigated, similar to what has already occurred for IBS.

CONCLUSION

FM is a disease that requires a treatment with multidisciplinary approach and nutrition approach has a strong potential. Our study is the first clinical trial that evaluate LFD-intervention integrated into FM patient treatment. The diet therapy, LFD, prescribed in this study was shown to have positive impact on FM symptoms, especially with painful hypersensitivity, a mechanism commonly mediating symptoms of FM and IBS. Also, LFD contributed to weight loss in the cohort studied, an advantage in FM sufferers with a high prevalence of overweightness. Moreover, LFD demonstrated to be a balance diet without nutritional risk described in addition to symptomatic improvement of FM.

Overall, this pilot study shows that a LFD could be one option to use as a potential dietary approach to FM treatment but these limited results imply cautious optimism towards use of LFD therapy for FM and, at a minimum indicate, more extensive studies must be conducted to verify its efficacy and safety.