INTRODUCTION

Osteoarthritis is a joint disease that affects 12-15% of the population aged 25 to 74 years old. The prevalence of this disease increases significantly with age 1.

The most common site of osteoarthritis is the knee. In the United States, this entity represents 37% of the population over 60 years of age; 12% are symptomatic and have functional repercussions. Prevalence is higher in people with older age and higher body mass index (BMI). There is a predominance of females in both the prevalence of osteoarthritis of the knee 2 and the replacement surgery 3. In Spain, the prevalence of osteoarthritis in relation to overweight in 2006 was 32.16% (34.9% in men and 20.93% in women) 4. The prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the general population in the 60-69 age group was 28.1% (18.1% in men and 37.2% in women) 5.

Overweight and obesity have been shown to be a predictive factor for the development of osteoarthritis. A BMI greater than 25 kg/m2 over 40 years increases the risk of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis 6. The mechanisms that link osteoarthritis with obesity are related to the chronic joint load 7, the altered body composition 8, and the situation of subacute inflammation 8).

The basis of any treatment of obesity is the modification of the hygienic-dietary patterns. It has been estimated that if the prevalence of obesity were reverted to levels ten years ago, 111,206 complete knee arthroplasties would be prevented 9. Several studies have estimated that up to half of cases of knee osteoarthritis can be avoided if obesity is eliminated as a risk factor 10.

The improvement of pain and functional disability is the main objective of the patient when considering a surgical treatment of arthropathy. The weight loss through conventional diet therapy has a positive effect on knee arthropathy 11. However, due to physical limitation this weight loss is discrete and can impair muscle mass 12. An alternative to conventional dietary treatment in the surgical patient is the meal-replacement diets. The effectiveness of these diets in the short term (three months) is contrasted. A meta-analysis in 2003 showed an average weight loss of between 6.19-6.50 kg (7% of total weight) compared to the control group, where a loss of 3.23-3.99 kg (4% of initial weight) was observed 13. Even so, there is little evidence of the effect of meal-replacement diets on quality of life in patients with arthropathy.

For this reason, we carried out a study with a meal-replacement diet on women with obesity and knee arthropathy candidates for orthopedic surgery. The main objective was to investigate the weight loss and the modification of body composition secondary to this type of diet, to evaluate the modification of the quality of life after the dietary intervention and to value its relationship with the change of anthropometric parameters and body composition.

METHODS

STUDY DESIGN

An intervention study of one branch with a meal-replacement diet with an oral nutritional supplement (Vegestart(r)) for three months was carried out in women with obesity (BMI greater than 30 kg/m2) and knee osteoarthritis pending orthopedic surgery. Patients with active oncologic disease and previous history of alcohol or toxic abuse were excluded.

The study was performed from January 2014 until July 2016. The study was carried out in patients belonging to the health area of Valladolid Este in Spain. These patients were referred from the Department of Traumatology to the Department of Endocrinology and Nutrition of the Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid for weight loss prior to orthopedic knee surgery.

PROCEDURES

All participants provided informed consent to a protocol approved by the local ethical review boards. This study was conducted according to the guidelines laid down in the Declaration of Helsinki and all procedures involving patients were approved by the Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid (HCUVA) ethics committee on 31-1-2014 with the code PI 14-151 CINV 13-60. All patients signed the informed consent and were included in the study. Patients received nutritional education and a low-fat hyperproteic hypocaloric diet (Table I). The diet was structured in six meals (breakfast, mid-morning, lunch, snack, dinner and late night snack). The lunch and dinner was replaced by an oral nutritional supplement called VEGEStart Complete(r), whose nutritional characteristics are described in table I.

Table I Macronutrient composition of diet and oral nutritional supplement Vegestart(r)

%TCV: total caloric value percentage.

The adherence of these diets was assessed each seven days with a phone call by a dietitian to improve compliment of the calorie restriction and macronutrient distribution. The diet compliance was verified with a 24-hour telephone dietary questionnaire every seven days and a 48-hour dietary survey of in face-to-face visits. All parameters were measured at baseline and these variables were repeated after three months.

STUDY VARIABLES

Anthropometry

The anthropometric evaluation of the subjects was performed by determination of weight, height and body mass index (BMI).

The weight was measured without clothing with an accuracy of ± 0.1 kg using a hand scale to the nearest 0.1 kg (Seca, Birmingham, UK). The height was measured with the patient standing up to the nearest centimeter using a stadiometer (Seca, Birmingham, UK). BMI was calculated using the formula: weight (kg)/height x height (m2).

The percentage of weight loss (% WL) was used to assess the relative weight difference.

Bioelectrical impedance measurement

A bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) was performed in all subjects. These measurements were performed before the start of the dietary intervention and three months after the intervention.

The BIA was performed on all subjects after a fast of at least five hours. It may be influenced by the degree of hydration, so subjects were warned that they could not exercise or drink alcohol within 48 hours prior to the test.

It was determined by a four-point single-decubitus device. An alternating current of 0.8 mA at 50 kHz produced by a calibrated signal generator (EFG, Akern It) was used and applied to the skin by adhesive electrodes placed on the back of the hand and right foot. Body composition was estimated with the Bodygraff(r) software.

The parameters analyzed with the BIA were: fat free mass and fat mass. All of them are represented as weight (kg) and percentage with respect to the total weight.

Quality of life test

Two different tests were used to evaluate the impact of the dietary intervention on health status and quality of life. The Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) test was used to evaluate the patient's quality of life before and after treatment. It is an instrument developed from an extensive battery of questionnaires used in the Medical Outcome Study (MOS) 14. In our design, we used the Spanish-translated version 15. It consists of 36 themes, which explore eight dimensions of health status: physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional and mental health. The score is directly proportional to the state of health (score ranges from 0 to 100).

The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) 16 was used to assess the functional limitation and influence of diet therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee and/or hip. We used the validated Spanish version 17. The test was performed face-to-face in front of the patient. This test is used to assess the functionality of the patient from three subscales with different scores: pain, stiffness, physical function, total (results from the sum of the three scores). The interpretation of the test is that the higher score means a worsening in any of the three areas (pain, stiffness and physical function) or in the total. To homogenize the data, the scores have been standardized from 0 to 100, where 0 means no alteration and 100 is the situation with the greatest alteration.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The data were analyzed using the SPSS statistical package (SPSS for Windows version 15.0, 2008 SPSS INC, Chicago, USA). An analysis of patients by intention to treat was performed. Sample size was calculated to detect a percentage of weight loss over 5%. The level of significance was conventionally set at p ≤ 0.05.

RESULTS

DEVELOPMENT OF THE STUDY

Eighty-one women with obesity and knee osteoarthritis pending orthopedic surgery were recruited between January 2014 and July 2016.

After three months of intervention, 75 (92.6%) patients maintained complete therapeutic adherence while six (7.40%) patients started the diet but did not complete it for different reasons (Fig. 1).

INITIAL EVALUATION

The mean age of the individuals was 62.23 (8.50) years.

Anthropometry and body composition

The initial weight was 99.33 (14.61) kg, while BMI was 40.80 (4.40) kg/m2.

In the analysis of body composition, fat mass and fat free mass were evaluated. A percentage of fat mass of 47.67% (5.19) with respect to the total weight and a percentage of fat free mass of 52.25% (5.24) were observed.

Quality of life

Test SF-36

To evaluate the patients' quality of life, the structured SF-36 test was performed in eight dimensions:

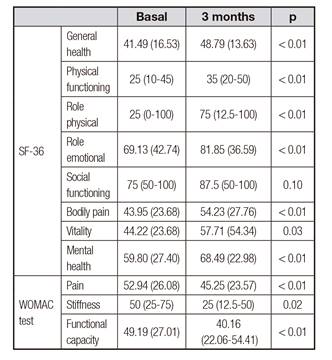

Table II Modification in quality of life test: SF-36 and WOMAC before and after three months of treatment

WOMAC

This test was used for the assessment of pain and its implication in the functionality of the patient. All patients had altered values at all levels (pain: 52.94% [26.08]; stiffness: 50% [25-75]; functional capacity: 49.19% [27.01]); as well as in total index: 49.24% [25.53]).

EFFECT OF DIETARY TREATMENT

Anthropometry and body composition

A weight loss rate of 8.23% (4.04) was observed after a three-month meal-replacement hypocaloric diet. There was a decrease in all body components. When assessing the change in body composition at three months, there was a relative decrease in the percentage of fat mass 2.66% (0.53-3.92) and a relative increase in the percentage of fat-free mass 2.30% (3.72) (Table III).

Quality of life

SF-36 test

An improvement was observed in total score (basal time: 49.35 [20.41], at three months: 58.71 [17.07], p < 0.01). We obtained an improvement rate of 15.97% (28.08).

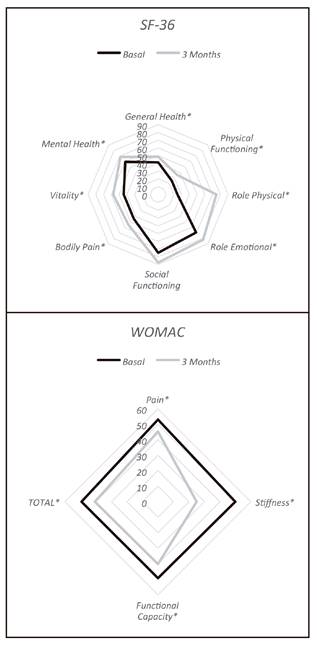

In the analysis of the different spheres (Table II) there was a significant improvement in all spheres except for social functioning (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 Variation of the different areas of the SF-36 and WOMAC tests before the start of the intervention and three months later. *Significant difference (p < 0.05).

WOMAC

The total score of WOMAC showed a significant improvement (basal time: 49.24% [25.53], at three months: 40.59% [21.76], p < 0.01). The decrease proportion of this test after intervention was 13.64% (0-35.68). There was significant improvement in the three spheres (Table II and Fig. 2).

Relationship of anthropometry changes with improvement of the quality of life

The percentage of weight loss showed a positive correlation with the percentage of variation of SF-36 (r = 0.23; p = 0.04), with the WOMAC pain domain (r = 0.34; p < 0.01), with the functional capacity domain (r = 0.31; p < 0.01), and the percentage change in WOMAC total score (r = 0.35; p < 0.01).

A multivariate analysis was performed to determine the influence of anthropometric changes on the modification of the quality of life scores. Improvement in quality of life was observed to be related to weight loss regardless of changes in body composition and age (Table IV). There was no relationship between the WOMAC test, weight loss and body composition (Table IV).

DISCUSSION

The effect of dietary treatment of obesity has shown several benefits on the complications associated with knee osteoarthritis. Even so, there are few studies that analyze the effect on quality of life in these patients when using a meal-replacement diet.

The SF-36 is a very useful test to evaluate the quality of life in a global way and in terms of different aspects affecting it. When comparing the score of the SF-36 test with the values of the test for the general Spanish population, a decrease in all values is observed except in the areas of role emotional, social functioning and mental health 18. This could be justified by habituation to chronic symptoms, or because of the difficulty of the test to assess these types of symptoms.

When comparing our data to those of similar populations (obese with degenerative arthropathy), quite a few similarities in the alteration of the different spheres of the SF-36 test are observed. When analyzing the excess weight, a previous study compared the obese versus non-obese population; in the age group between 55 and 64 years worse scores in the population with obesity in spheres of physical functioning, role physical, pain, general health and vitality were observed, while in other spheres the score was similar 19. Similar levels were also observed in populations with the same characteristics as ours in which different comorbidities are combined. In this way, it has been shown that the SF-36 physical spheres score worsens with the increase in the number of comorbidities, and particularly with the presence of obesity 20) (21.

Given the special characteristics of these patients, a more specific test for arthropathy, such as WOMAC, was performed. When analyzing the WOMAC, a score of pain, stiffness, functional capacity and the total of the sum close to half were observed. The levels of pain and altered functional capacity in the WOMAC test are variable according to the study ranged from lower scores around 20% 22 till higher scores around 40-50% in populations with obesity 23. This data means that higher values of BMI produce worse values of WOMAC 24. This would justify that the values obtained in our study were in a range of greater pain and disability. The pain and physical situation scores would resemble those of the other test performed (SF-36). This situation has been evaluated in other studies, with similar findings and improvement after arthroplasty replacement 25. The effect of dietary treatment on these parameters does not have such clear evidence in the literature.

The results on weight loss in our study are similar to those performed with the same intervention. In a study by De Luis et al. in a population of patients with arthropathy, a greater weight loss was observed in the treatment group with a commercial diet compared to dietary advice 26, with a mean weight loss of 7.7 kg compared to 3.92 kg in the control group. In another meta-analysis by Anderson, it was found that there was a greater percentage of weight loss, up to 9.3% in men and 8.6% in women, with an initial BMI ranged from 28 to 35 kg/m2. These data were similar to what was done in our study 27.

When the change in body composition was analyzed, a decrease in the percentage of fat mass that was associated with a relative increase of fat-free mass was observed. This data shows that maintaining an adequate protein intake can help to reduce excess muscle loss, despite caloric restriction. This topic has been observed in different studies with hyperproteic meal-replacement diets of one or more meals 28) (29.

The main symptoms that are usually evaluated in these patients are the improvement of pain and stiffness. In the WOMAC test, an improvement in the parameters of stiffness and physical function was observed. This change in functional capacity score is seen in multiple studies associated with weight loss in patients with arthropathy. In 2010, a meta-analysis on long-term weight loss in obese elderly patients showed that functional impairment and overall quality of life improved with weight loss in obese elderly patients 11.

We observed an improvement in all of the items of the SF-36 test after intervention except for social functioning. This situation could be due to two reasons: the baseline scores were close to the average of the general Spanish population, and the measurement of this sphere through a single question with three degrees makes it difficult to show differences.

In the SF-36 test, although there were no differences in social functioning, there was an improvement in mental health. This situation related to the decrease of pain and the improvement of the functional capacity in the evaluated tests relates the influence of these two characteristics to the psychic situation of the patients.

The reduction of weight in the context of the treatment of osteoarthritis of different locations, especially those of load (hip and knee), has a positive effect on pain. The effect starts to be effective with weight losses above 5% 30. This relationship has been analyzed in many studies of osteoarthritis of the knee using the WOMAC 31 with greater effect in those patients with greater weight loss. This effect is enhanced if there is a long-term maintenance of weight loss 32.

In our study, there were isolated correlations between the greater weight loss and the improvement of the WOMAC in its total score, in the field of pain and functional capacity. This approach has recently been observed in a study where the percentage of weight change was associated with the WOMAC score, both gain and weight loss 33. In the case of the analysis of the improvement of the articular functionality after the loss of weight the data are variable in the literature. In several cases, a functional improvement was observed in relation to weight loss in diet-only management 34, with intensive diet 35, or a combination of diet and exercise combined 36.

An independent relationship was observed in the weight loss with the intensity of the SF-36 test improvement. This relationship did not occur with the WOMAC test. The differences found between both tests in obese patients with arthropathy in relation to weight loss can be related to a partial improvement in pain and functional capacity, and with the positive effect that the weight loss had on the patient's well-being. It has been observed that this score improves more in obese patients than in non-obese patients after moderate weight control 37. Therefore, these results may be due to the influence of weight loss on quality of life in other aspects than mechanical ones, such as psychological and social factors.

The main limitation of our study was the absence of a control group with a different dietary intervention to be able to categorize the impact of the diet itself on the quality of life. Second, the inclusion of only women limits the extrapolation of study data, but this decision was made due to the higher prevalence of osteoarthritis of the knee in women. Finally, it would be interesting to carry out a long-term assessment of the maintenance of weight loss and the change of the quality of life of the patient.

CONCLUSIONS

A short term dietary treatment through a meal replacement diet in obese women with knee osteoarthritis pending surgery showed: a weight decrease between 5-10% with a relative decrease of fat mass and relative increase of fat-free mass; an improvement in the quality of life measured by the SF-36 test in all its spheres except for social functioning; and improvement in all dimensions of the WOMAC test. Adjusting for age and body composition weight loss showed an independent relationship with SF-36 improvement. Further studies are needed to evaluate this dietary intervention in patients with other arthropaty and during long term interventions.