INTRODUCTION

Head and neck cancer includes oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, hypopharynx and paranasal sinus 1. The majority are squamous cell carcinomas, affecting specially men, with a male to female ratio ranging from 2:1 to 4:1 2. Some risk factors have been described, including alcohol abuse, smokeless tobacco and papilloma virus (VPH) infection 3. Its incidence is approximately 550,000 cases and 300,000 deaths per year 1. In Europe, during 2012, 250,000 new cases and 63,500 deaths were reported 4.

Treatment goals include local disease control and increase of the survival with minimal adjacent tissue damage; more than 60% of patients with head-neck cancer can be cured with surgery and/or radiotherapy (RT). Treatment options are determined by the disease localization, extension and histology. Patients with stage I and II are treated with surgery or radiotherapy (curative rate 77-91%), while stages III and IV require the combination of extensive surgery, radiotherapy or chemoradiation (curative rate ranges 25-61% depending on tumor localization) 2.

Malnutrition affects 30-50% of patients with head-neck tumors, especially those localized in the oropharynx or the hypopharynx; around 30% have severe malnutrition during the six months prior to diagnosis. Chemotherapy worsens the nutritional condition due to tract digestive system related symptoms including taste loss, mucositis, xerostomia, nauseas and vomits 5. Malnutrition in head-neck cancer patients has been related to a higher rate of postsurgical complications, worse treatment response and higher tumor recurrence. Malnutrition increases the risk of infections, treatment related toxicity and decreases quality/expectative of life 6. Several studies have suggested more treatment interruptions and worse treatment effectiveness related to mucositis 7; fat-free body mass loss has been proposed as the responsible for the increase in mortality and worse prognosis related to malnutrition in cancer patients 8.

Early nutrition support (ENS) seems to improve the outcome in patients with gastrointestinal tract and head-neck tumors who receive RT 5, suggesting that maintaining body weight stable avoids deterioration in nutritional status 5. International guidelines suggest early dietary counselling and oral supplements for avoiding treatment related weight loss and not-planned interruptions in RT 9; even the improvement in nutritional status could be related to decreased RT toxicity 5.

Based on this, our aim was to evaluate the effect of early nutritional support using dietary counselling, oral supplements or enteral nutrition on anthropometric, biochemical markers and RT tolerance in patients with head-neck cancer.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

PATIENTS

The Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario Reina Sofía (Cordoba, Spain) approved the study, which was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and according to national and international guidelines. Every individual or family member accepted the informed consent before inclusion into the study. We included both sex patients, older that 18-years old, with minimal two points in the malnutrition screening tool (MUST) 10. All patients had a head-neck cancer requiring RT and they were evaluated minimal in two different occasions in our outpatient clinic before the inclusion into the study. All the evaluated patients that fulfilled the inclusion criteria were included. Patients were treated according to the current guidelines for head-neck cancer 11,12. Radiotherapy consisted in external radiation using high-energy photon beams (4-6 MV) generated by a linear accelerator. The total doses was 46-70 Gy divided in 1.8-2 Gy per day, five days per week (doses per week: 10 Gy). RT tolerance was measured using the oncology toxicity grading (RTOG) as follows 9:

Grade 0: none.

Grade 1: asymptomatic, mild symptoms.

Grade 2: local symptoms; intervention is required.

Grade 3: severe without life threatening effect.

Grade 4: life threatening, urgent intervention is required.

Grade 5: death related to adverse effect.

For our analysis, the five levels of the RTOG were combined in three different groups as follows: good tolerance, grades 0-1; regular tolerance, grades 2-3; and bad tolerance, grades 4-5.

CLINICAL EVALUATION

Anthropometric evaluation included body mass index (BMI) calculated as weight (kg)/height (m2). The percentage of weight loss (%EWL) was calculated using the following formula: (initial weight -follow-up weight)/(initial weight- ideal body weight) x 100; the ideal body weight was calculated for a BMI of 21 kg/m2 in women and 23 kg/m2 for men 13,14. The mean Karnofsky index (KI) 15 was calculated for each patient.

Mucositis evaluation was performed according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification 16:

Grade 0: none.

Grade I (mild): oral soreness erythema.

Grade II (moderate): oral erythema, ulcers, solid diet tolerated.

Grade III (severe): oral erythema, ulcers, liquid diet only.

Grade IV (life-threatening): oral erythema, ulcers, oral alimentation impossible.

Epithelitis evaluation was performed following the scale:

Grade 0: no change from baseline, asymptomatic.

Grade 1: follicular faint or dull erythema epilation, dry desquamation, decreased sweating.

Grade 2: bright erythema, confluent moist desquamation, pitting edema.

Grade 3: ulceration, hemorrhage, necrosis.

This scale was adapted from the toxicity criteria of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer 17.

Anemia was also divided in four different groups according to the hemoglobin (Hb) level:

NUTRITIONAL INTERVENTION

All patients received nutritional counselling based on the Mediterranean diet 18, oral supplements/enteral nutrition and a close follow-up by a nutritionist in our hospital. The volume of enteral nutrition per day was adjusted according to the basal situation of the patient, and was modified according to the food intake and the presence of RT related complications.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Normality distribution of the data was determined using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables were reported in percentage values. Univariate analysis in continuous variables was performed using the Wilcoxon test. Chi-squared compared categorical data. Cox regression curves were performed for the evaluation of mortality associated variables. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software v15. Data in graphs are expressed as mean ± SEM. p-values < 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 102 patients with head-neck cancer were included in the study. The clinical features of patients are summarized in Table I. In our group, 47.9% of patients were active smokers and 42.1% had active alcohol abuse. Otalgia and oral ulcer were the most prevalent symptoms (23.5% and 20.6% respectively), related to the most common primary tumor localization (oropharynx, 34.3%; larynx, 21.4%). A stage IV of disease was observed in 76% of patients when included; stage IVa was the most prevalent (63%). The mean Karnofsky index (KI) was 89.2%.

Table I General characteristics of the studied population

*Radiotherapy was a therapeutic option in all included patients.

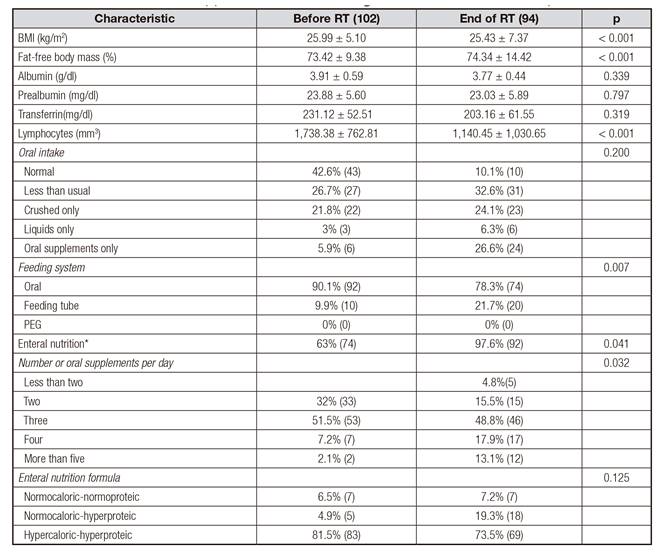

Early nutritional support was systematically performed in all patients before RT. More than 55% had decreased or different oral intake before RT but almost 90% of the included patients had abnormal oral intake after RT. At that moment, enteral nutrition was the only support in 26.6% of patients (Table II) while more than 20% required a feeding tube. A non-clinically significant decreased BMI was observed after RT (p < 0.001), with an increase in fat-free body mass (p < 0.001). Interestingly, biochemical markers including albumin, prealbumin and transferrin remained stable after the treatment period (Table II).

Table II Nutritional support before and during RT in head-neck cancer patients

PEG: percutaneous enteral gastrostomy. *Enteral nutrition refers to oral supplements or total enteral nutrition.

In our group, more than 55% of patients tolerated well the RT, 92% of cases attended to all the originally planned RT sessions and only 27.7% of patients interrupted the RT schedule, while 29.7% required hospitalization. More than 60% of patients had grade 0-1 mucositis and epithelitis and more than a half tolerated the RT treatment adequately (Table III).

In our study, eight patients died. These patients characteristically had lower KI (81.25% vs 90.18%; p < 0.01), higher weight loss before RT (19.9 vs 4.6%; p < 0.001), higher grade of mucositis (p < 0.05) and higher epithelitis (p < 0.05). There were no significant differences between age or initial biochemical nutrition parameters.

Interestingly, patients with previous caloric malnutrition (defined as minimal body weight loss in the last three months of 5%), had a higher non-completion rate of RT compared to those patients without caloric malnutrition (66.5 vs 97.8%, respectively; p < 0.001). Those patients requiring induction or concomitant chemotherapy had more non-desired RT interruptions (p < 0.05) and higher number of hospitalizations (p < 0.05) (data non-shown).

DISCUSSION

The majority of patients with head-neck cancer have locally advanced disease at diagnosis. For this reason, treatment is usually aggressive, with a therapeutic goal of achieving a cure while minimizing toxicity 6. Patients are frequently malnourished prior to the beginning of treatment. Malnutrition in head-neck cancer affects 30-50% of patients 6,7,19; since malnutrition has been related to higher post-operative complication rates, worse treatment response and higher tumor recurrence, early nutritional intervention is required 6. Enteral nutrition is based on the use of oral supplements or gastro-enteric tube feeding; its goal is to guarantee and, if possible, increase the nutrients intake when oral intake is not adequate or safe 9.

Our studied population presented the most common risk factors and staging at diagnosis that are currently described in head-neck cancer patients 2,20. It represents, then, an appropriate group of patients for analyzing results and driving conclusions.

It is well known that some nutritional parameters should be controlled in cancer patients in order to initiate early interventions and to prevent excessive deficits 21. Nutritional evaluation should be performed frequently and ENS should be initiated when deficits are detected (level of evidence C); according to the current guidelines, enteral nutrition with standard formulas should be initiated if malnutrition is detected or if oral intake has decreased during the last 7-10 days 9. Intensive early nutrition support with regular follow-up helped attenuate the natural weight loss history of treatment in our study group, as it has been previously reported 5. ESPEN guidelines suggest nutritional counseling and oral supplements use in patients under chemo-radiotherapy for avoiding weight loss 9,21; oral, enteral or parenteral route may be used depending on the clinical situation of each patient and specially, the level of function of the gastrointestinal tract 21.

Energy requirements in cancer patients should be similar to those of healthy subjects; protein intake should be above

1 g/kg/day, or even above 1.5 g/kg/day 21. Clinical features and treatment options in head-neck tumors may make reaching these goals difficult, suggesting the importance and necessity of nutritional supplements in these group of patients.

A slightly decrease in weight loss and BMI (< 0.6 kg/m2) was observed in our patients, whereas serum proteins and nutritional markers remained stable. Only lymphocytes were decreased, which could be probably related to chemotherapy effects or to the tumor itself 22. Despite body weight loss, an increase in fat-free body mass was observed. Similar results have been reported in randomized studies evaluating early and intensive nutrition intervention in patients with gastrointestinal and head-neck tumors 5 and advanced stage IV solid tumors 23.

It is well known that RT is associated with acute side effects (whose incidence increases when concomitant or induction chemotherapy is administered), especially oral mucositis 24,25. In our group, the incidence of severe mucositis was lower than 10%, contrasting with other studies reporting mucositis rates of 89-97% in head-neck cancer patients receiving RT 26. The incidence of severe mucositis (grades 3-4) has been reported in 34-53% of patients depending on the RT method 26. Interruption rates of 86% have been also described, especially due to mucositis 27. Interestingly, a four-fold decrease in non-organized interruptions has been observed in our study group.

Oral mucositis has been related to unscheduled breaks or delays in RT administration (24,25). Unscheduled RT interruptions were observed only in 22% of the evaluated patients; this rate tends to be higher in other reports 28. Even RT interruption rates of 36% exclusively due to mucositis have been previously described (27). Remarkably, it has been suggested that when inadvertent or deliberated gaps in RT occur, reduced tumor control may result because of accelerated tumor clonogen repopulation 28. Based on this, nutritional counseling and oral supplements use are recognized as important tools to reduce weight loss and avoid treatment interruptions in patients receiving chemo-radiotherapy 9.

Compared to clinical guidelines which suggest the use of standard supplements 9,21, we mostly used specific enteral formulas depending on the patient's nutritional status, daily oral intake and regular use of the nutrition supplements. In our group, previous caloric malnutrition and combined chemo-radiotherapy was related to worse treatment adherence and fulfillment; probably in these cases, enteral nutrition and/oral supplements should be started earlier, since the diagnosis is performed.

A limitation of this study was the number of participants, the absence of a control group and the absence of other anthropometric and nutritional markers (for example, dynamometry or tomography guided fat-free mass measuring). Despite this, the ENS in our group showed relevant clinical benefits.

In conclusion, treatment in head-neck cancer patients requires a multidisciplinary approach including ENS. Enteral nutrition should be started previous to the systemic treatment and kept during and after it, in order to decrease weight loss. This strategy would allow to decrease treatment interruptions and systemic related complications and improve quality of life. Nutritional advice and oral supplements should be started earlier in previous malnourished patients and in those receiving combined chemo-radiotherapy or induction chemotherapy. Randomized, large studies are required to confirm and increase these results.