INTRODUCTION

Malnutrition is a prevalent problem in hospitalized patients 1,2. It is such an important problem that the Council of Europe has published the resolution "Food and nutritional care in hospitals: how to prevent undernutrition. Report and recommendations" 3. The association between dysphagia and nutritional status has been investigated. In a systematic review of nursing home patients, the factors most consistently associated with malnutrition were swallowing/chewing difficulties 4. In patients with stroke, the ratio of being malnourished were higher among subjects with dysphagia compared with subjects with intact swallowing 5.

Complications of dysphagia include dehydration, malnutrition, depression, pneumonia and death 6. Moreover, dysphagia is a symptom, not a disease, and patients with dysphagia may have no important evidence of objective swallowing dysfunction. Some instruments have been developed to quantify patient dysphagia symptoms. The 10-item eating assessment tool (EAT-10) is a validated, self-administered, symptomatic outcome tool that is commonly used in hospitals 7. This questionnaire was developed by a multidisciplinary team of dysphagia experts and has high test-retest reliability and good internal consistency 8. The EAT-10 has been shown efficacious in detecting initial symptom severity and in monitoring nutritional support efficacy 9. An EAT-10 score ≥ 3 is abnormal and indicates the presence of swallowing difficulties.

On the other hand, malnutrition is often unrecognised and untreated. Anthropometry measurements are generally considered as the single most easily obtainable method by which to assess nutritional state. Biochemical measurements such as serum albumin and prealbumin are also well known as markers for the malnutrition 10. The evaluation of nutritional conditions in the elderly population demands the utilization of easy and fast methods. The Mini-Nutritional Assessment (MNA) test, which attributes scores based on dietetic, anthropometric, subjective and global assessments, has been evaluated in geriatric patients and meets these requirements 11,12,13.

The purpose of this investigation was to investigate the associations between nutritional status by MNA test and dysphagia by EAT-10 in elderly individuals requiring nutritional oral care in an acute hospital.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

SUBJECTS

This was a cross-sectional survey covering a sample of 560 elderly individuals aged 65 years or older who required nutritional care in an acute hospital. The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Medicine School (University of Valladolid). All participants provided informed consent prior to enrollment. Information was gathered over the course of 2015-2016. The inclusion criteria required that individuals were at least 65 years of age, admission to the acute hospital and requiring nutritional oral care because the intake did not reach 70% of the recommendations according to the formula of Harris Benedict 14 for at least the last month. Exclusion criteria were inability to respond the EAT-10 and terminal-stage malignancy.

PROCEDURES

As anthropometric parameters, weight, height and body mass index (BMI) have been included. Venous blood samples were collected in EDTA-treated and plain tubes after a 12 hour overnight fast for analysis of glucose, creatinine, sodium, potassium, albumin, prealbumin and transferrin. The EAT-10 and MNA tests were performed by the same dietitian. The days of hospital stay and mortality during hospitalization were recorded during admission. Charlson score was calculated in all subjects 15.

ANTHROPOMETRIC MEASUREMENTS

Body weight was measured to an accuracy of 0.1 kg and height was measured in centimetres using a stadiometer. Body mass index computed as body weight in kilograms/height (in m2).

BIOCHEMICAL ASSAYS

Fasting blood samples were drawn for measurement of glucose (70-110 mg/dl), creatinine (0.6-1.1 mg/dl), sodium (135-145 meq/l), potassium (3.5-5 meq/l), albumin (3,5-4,5 gr/dl), prealbumin (18-28 mg/dl) and transferrin (250-350 mg/dl) (Hitachi, ATM, Manheim, Germany).

EAT-10 TEST

Participants were divided into two groups: an EAT-10 score between 0 and 2 and an EAT-10 score between 3 and 40, because a score ≥ 3 is abnormal and indicates the presence of swallowing difficulties 15. The EAT-10 consists of ten questions about the severity of symptoms of oropharyngeal dysphagia. Each question will be scored from 0 (no problem) to 4 (important problem). Elevated EAT-10 score indicates a high level of dysphagia severity.

MINI NUTRITIONAL ASSESSMENT TEST

The standard MNA test is composed of simple measurements and questions that can be completed in about fifteen minutes. MNA consists of 18 questions divided into four blocks. The first group refers to anthropometric parameters (BMI, brachial circumference, leg circumference, recent weight loss in the last three months), overall assessment (daily medication, diseases in the last three months, neuropsychological problems, skin lesions, mobility), dietary parameters (number of meals per day, type of food consumed, fluid consumption, way of eating) and evaluation (subjective self-assessment of nutritional status compared with other patients) 16. According to this test, patients scoring less than 17 points are classified as malnourished patients; patients with scores between 17 and 23.5, as at risk of malnutrition; and patients with scores ≥ 23.5, as well-nourished.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The sample size was calculated taking into account a coefficient correlation of EAT-10 score and MNA score of 0.5 with a power of 0.9 and a statistical significance < 0.05 (n = 500). The results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. The distribution of variables was analysed with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Quantitative variables with normal distribution were analysed with the Student's t-test. Non-parametric variables were analysed using the Mann-Whitney U test. ANOVA test with Bonferroni post-hoc was used in variables with more than two groups. Discrete variables were analysed with the Chi-squared test, with Yates correction as necessary, and Fisher's test. Correlation analysis was realized with Pearson test. Multiple regression analysis was used to examine whether the EAT-10 has an independent effect on hospital stance and MNA test by adjusting for covariates such as age, gender and Charlson score. Logistic regression analysis was used to examine whether the EAT-10 has an independent effect on mortality by adjusting for the same covariates. A p-value under 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

A total of 560 patients were enrolled; mean age was 80.3 ± 8.3 years, weight was 56.4 ± 13.1 kg and BMI, 22.3 ± 4.3 kg/m2. The sex distribution of patients was 246 (43.8%) males and 314 (56.2%) females. In males, mean age was 80.2 ± 8.0 years, weight 63.1 ± 12.1 kg and BMI 22.6 ± 4.0. In females, mean age was 81.1 ± 8.9 years, weight was 53.9 ± 8.1 kg and BMI, 22.1 ± 4.8. Common diseases included dementia 46.6%, cerebrovascular disease 18.3%, cancer 15.4%, chronic neurological disease such as Parkinson disease 6.2%, chronic heart failure 6.8%, acute infections 5.6% and digestive disease 1.1%.

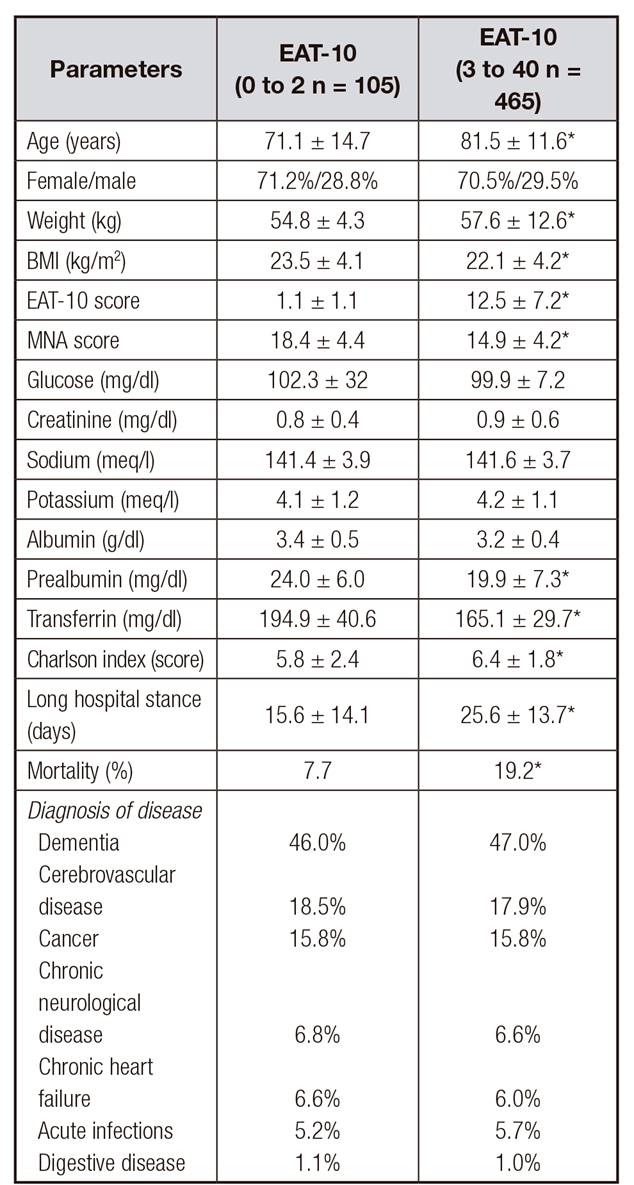

The mean EAT 10 was 11.2 ± 0.89, median 10 and interquartile range 6-15. Table 1 shows the distribution of patients according to their EAT-10 score, and a total of 465 (83.1%) elderly patients had EAT-10 scores between 3 and 40, indicating the presence of dysphagia. These patients have lower levels of albumin, prealbumin and transferrin than patients with an EAT-10 test 10 < 3. Anthropometric parameters such as weight and BMI were lower in elderly subjects with EAT-10 score above 3 than subjects with an EAT-10 score < 3. Elderly patients with the EAT-10 score above 3 had a Charlson score, hospital stay and mortality higher than those with an EAT-10 score lower than 3. There were no differences in the distribution of disease types in each group (Table 1).

Table I. The eat score, differences between normal group EAT-10 (0 to 2 n = 105) and pathologic group EAT-10 (3 to 40 n = 465)

MNA: Mini Nutritional Assessment test;

EAT-10: 10-item eating assessment tool; BMI: Body mass index.

*p < 0.05 between groups.

The mean MNA test was 15.2 ± 1.1, median 15 and interquartile rage 11-18.5. Table 2 shows the distribution of patients according their MNA score. A total of 340 (60.7%) elderly patients had MNA scores under 17, indicating the presence of malnutrition; 177 subjects (31.6%) had a MNA score of 17-23.5, indicating a risk of malnutrition; and 33 subjects well-nourished. Anthropometric parameters such as weight and BMI were lower in elderly subjects with MNA scores under 17 and 17-23.5 than in subjects with MNA scores > 23. Elderly patients with MNA scores under 17 and 17-23.5 had a higher Charlson score, hospital stay and mortality than those with MNA scores > 23.5. There were no differences in the distribution of disease types in each group (Table 2).

Table II. The MNA test differences among malnourished (< 17; n = 340), at risk of malnutrition (17-23; n = 177) and normal (> 23; n = 33)

MNA: Mini Nutritional Assessment test;

EAT 10: 10-item eating assessment tool;

BMI: body mass index

*p < 0.05 among groups with basal value (MNA score < 17) Anova Test Bonferroni post hoc test ex.

In the correlation analysis of the total score of the EAT-10 test with the different variables, a negative correlation was detected between the score of the EAT-10 test and the weight (r = -0.26; p = 0.43), MNA score (r = -0.43; p = 0.001) and hospital stance (r = -0.12; p = 0.02).

In the second correlation analysis of the total score of the MNA test with the different variables, a negative correlation was detected between the score of the MNA test and EAT-10 test (r = -0.43; p = 0.001), Charlson score (r = -0.16; p = 0.001) and hospital stay (r = -0.11; p = 0.03). A positive correlation was detected between the score of the MNA test and weight (r = 0.54; p = 0.001) and IMC (r = 0.55; p = 0.001).

Multiple regression analysis was used to examine whether the EAT-10 and MNA tests have an independent effect on hospital stay by adjusting for covariates such as age, gender, type of diseases and Charlson score. There was no multicollinearity between variables. The MNA score and EAT-10 score were independently associated with hospital stay Beta -0.111 (CI 95%: -0.031- -0.78) and Beta 0.122 (CI 95%: 0.038-0.43), respectively. The same model with MNA score as dependent variable showed that EAT-10 score was an independent variable Beta -0.236 (CI 95%: -0.213-0.09).

Logistic regression analysis was used to examine whether the EAT-10 and MNA tests have an independent effect on mortality by adjusting for age, gender, type of diseases and Charlson score. There was no multicollinearity between variables. The MNA score and EAT-10 score were independently associated with mortality Odds ratio 0.91 (CI 95%: 0.84-0.96) and 1.040 (CI 95%: 1.008-1.074), respectively.

DISCUSSION

Our study addressed the inverse association between the 10-item questionnaire (EAT-10) score and the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) score in elderly individuals requiring oral nutritional care in an acute hospital. Both scores (MNA and EAT-10) were associated with poor outcome in this group of elderly subjects, regardless of their hospital stay and mortality.

Dysphagia is a prevalent and severe motility disorder with a very poor prognosis. However, despite this high prevalence, mortality, morbidity and cost caused by nutritional and respiratory complications, dysphagia is mostly underdiagnosed and undertreated. All this may be due to the low level of awareness among healthcare professionals, and the lack of clinical tools for bedside screening of dysphagia contribute to this fact. The EAT-10 includes questions about dysphagia symptoms. Our study population presented many comorbidities, impaired nutritional status and high prevalence of dysphagia, because all of them had an oral nutritional problem which made normal intake impossible for at least the last month. The EAT-10 was associated with nutritional status in our elderly sample as reported by Wakabayashi et al. 17. The frequencies of at risk of undernutrition (31.6%) and malnourished status (60.7%) in our population were higher than those presented in the literature because our sample is a group of hospitalized patients selected with an ingestion that does not reach the recommendations.

MNA is associated with biochemical indicators of nutritional status, and it is an easy-to-use and inexpensive tool in clinical practice, which reinforces its importance in the clinical assessment of institutionalized patients 18,19. Causes of malnutrition in hospitalized patients are related to acute and chronic illness, or to environmental and social circumstances or poor nutritional choices 20. All of these factors may play a role in the etiology of sarcopenia 21, and contribute to sarcopenic dysphagia 22 in elderly subjects. Secondarily, dysphagia can cause nutrition-related sarcopenia. Our results suggest dysphagia represents another cause of malnutrition among elderly hospitalized patients. Therefore, dysphagia evaluation is very important for elderly patients requiring acute care in a hospital with an EAT-10 score > 3.

Studies have frequently shown that malnutrition has important implications for recovery in some diseases and is associated with increased mortality, morbidity, hospital stance and higher treatment costs 23,24. This is also what we have detected for malnutrition in our study. Also, we found that dysphagia is a risk factor for mortality and increases length of stay during hospitalization, as reported by Carrion et al. 25.

The strength of the EAT-10 is that it is a rapid and easily scored questionnaire. There are other methods to screen and assess swallowing function, such as pulse oximetry, cervical auscultation, volume-viscosity swallow test, videoendoscopic evaluation and videofluoroscopic evaluation. However, these methods are not easy to perform, compared to the EAT-10 26.

Some limitations of our study must be considered. First, a special sample of subjects was evaluated (elderly, acute hospitalization and a decrease in oral intake) and, subsequently, the data were not generalizable. Finally, there is no evaluation of the functional or social status of the patients, which may be factors that influence our results.

In conclusion, dysphagia assessed by the EAT-10 is associated with nutritional status in elderly subjects requiring acute hospitalization. Subsequently, malnutrition and dysphagia were associated with poor outcome such as hospital stance and mortality. Based on these findings, future studies should clarify the effect of routine systematic screening and assessment for malnutrition and dysphagia as part of standard elderly evaluation among elderly hospitalized patients requiring oral nutritional care. However, the position statements of the European Society of Swallowing Disorders recommend clinical screening of dysphagia, malnutrition and hydration status among hospitalized elderly subjects to provide specific nutritional support 27.