INTRODUCTION

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is a broad term generally representing a measure of happiness or satisfaction with life 1 and includes social, mental and physical well-being 2 as well as other factors such as purpose, fulfilment, motivation, social engagement, role, and participation in daily activities 3. In recent years, HRQoL has aroused the interest of the public health community as a relevant measure related to childhood obesity and lifestyle 4,5.

In contemporary society, food habits are one of the most frequent human behaviours, and healthy food habits generally have a strong participative role in the overall state of well-being 6. Science has reported that adherence to the Mediterranean diet is associated with positive effects on specific components of HRQoL and subjective happiness 7. Besides, it is also associated with physical and mental health status as well as HRQoL. Likewise, children's food habits have an influence on health in later life, present associations with different factors of mental wellness 8, and can be protective factors for subjective well-being in children 9. Therefore, children's food habits should be monitored.

Childhood obesity is a multifactorial health condition and is associated with psychosocial alterations, including deficiencies in social co-existence, with consequences for HRQoL 4,5. It has been observed that obese children tend to have affective problems, which may negatively affect their academic performance 10. Childhood obesity has come up as a threat to the physical as well as the mental health of children and adolescents 11. Therefore, the relationship between mental illness (i.e., HRQoL), and obesity has been increasingly recognised in the paediatric population. However, research exploring the association between nutritional level and HRQoL in children has been inconsistent. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to determinate the association between children's food habits (i.e., Mediterranean diet adherence), weight status and HRQoL in Chilean schoolchildren.

MATERIAL AND METHOD

This cross-sectional study included 634 schoolchildren, girls (n = 282, 11.86 ± 0.82 years) and boys (n = 352, 12.02 ± 0.87 years) from four primary public schools in Chile selected by convenience. The sample size is similar to previous studies 12,13. Parents and guardians were informed about the study and provided signed written consent for participation. Additionally, all children gave their written assent on the day of the assessment.

The inclusion criteria were: a) presenting informed consent of the parents and the assent of the participant; b) belong to educational centres, and c) be between 10 and 13 years of age. The exclusion criteria were having a musculoskeletal disorder or any other known medical condition, which might alter the participant's health and physical activity levels. Moreover, schoolchildren with physical, sensorial or intellectual disabilities were excluded.

The investigation complied with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013) and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad de La Frontera, Chile (DFP16-0013). The tests were explained to all the participants before the study began.

MATERIAL

ANTHROPOMETRIC ASSESSMENT

The body mass index (BMI), calculated as the body mass divided by the square of the height in metres (kg/m2), was used to estimate the degree of obesity. The body mass (kg) was measured using a TANITA scale, model Scale Plus UM - 028 (Tokyo, Japan); the children were weighed in their underclothes, without shoes, and the height (m) was estimated with a Seca® stadiometer, model 214 (Hamburg, Germany), graduated in mm. The BMI is shown in the growth table of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Overweight and Obesity, verifying the corresponding age and the sex-related percentile. Child obesity is defined as a BMI equal to or greater than the 95th percentile and overweight as a BMI equal to or greater than the 85th percentile among children of the same age and sex 14. The waist circumference (WC) was measured using a Seca® tape measure model 201 (Hamburg, Germany) at the height of the umbilical scar 15. The waist-to-height ratio (WtHR) was obtained by dividing the WC by the height and was used as a tool for estimating the accumulation of fat in the central zone of the body following international standards 16. To measure the % body fat (BF), we used the tricipital fold and the subscapular fold (Lange Skinfold Caliper,102-602L, Minneapolis, USA) applying Slaughter's formula 17 D ¢ D: Girls: % B F = 1.33 (tricipital + subscapular) - 0.013 (tricipital + subscapular)2 - 2.5; Boys: % BF = 1.21 (tricipital + subscapular) - 0.008 (tricipital + subscapular)2 - 1.7.

The research assistant was submitted to the test-retest (n= 64, 10% of study sample) protocol to verify its technical measurement error with an intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC), in WC (ICC = 0.94), tricipital fold (ICC = 0.91) and subscapular fold (ICC = 0.91).

NUTRITIONAL LEVEL ACCORDING CHILDREN'S FOOD HABITS

The children's food habits were assessed by the Krece Plus test 18, which is a tool to assess the eating pattern and the relationship with the nutritional status based on the Mediterranean diet. The questionnaire has 15 items and the format assesses a set of items about the food consumed in the diet. Each item has a score of +1 or -1, depending on whether it approximates the ideal of the Mediterranean diet. The total points are added, and according to the score the nutritional status is classified as follows:

QUALITY OF LIFE

The HRQoL for Children and Young People was measured with the KIDSCREEN-10 questionnaire 19. The HRQoL was assessed using the Spanish version. This instrument of self-report consists of 10 items derived from the version of the KIDSCREEN-27 questionnaire. It is answered using a Likert scale with 5 possibilities (not at all, slightly, moderately, very often, always). The scale was reset to have a score from 0 to 10.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v23.0 software (SPSSTM IBM Corporation, NY, USA). Normal distribution was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. For continuous variables, values are presented as mean and standard deviation, whereas for categorical variables data are presented as proportions. Differences between weight status and nutritional level were determined using the one-way ANOVA. To determine the association between HRQoL with nutritional level and anthropometric parameters, a multivariable logistic regression was used. The chi-squared test was applied to compare proportions according to weight status and nutritional level about different questions of quality of life. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Table I shows the results according to nutritional level, which considered children's food habits (i.e., Mediterranean diet adherence). The schoolchildren with high nutritional levels reported higher quality of life (p = 0.018) and presented lower BMI, WC and WtHR (p < 0.001).

Table I. Characteristics of sample study according nutritional level

Data are presented as mean and SD. p < 0.05 considered statistically significant. BMI: body max index; WC: waist circumference; WtHR: waist-to-height ratio; BF: body fat. (A) low nutritional level, (B) denotes moderate nutritional level and (C) high nutritional level in post hoc analysis.

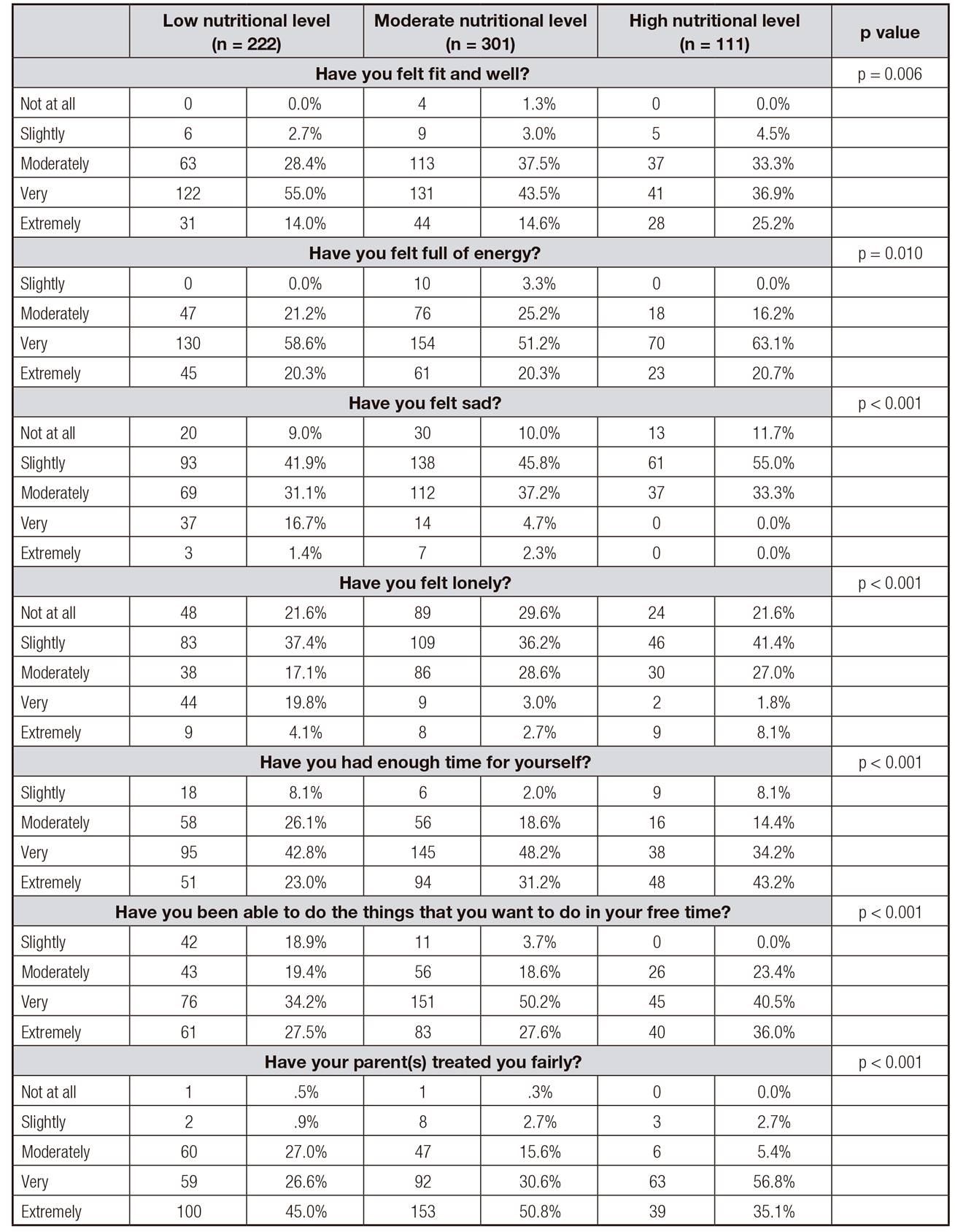

The distribution of the response (significantly different) between groups according to nutritional level in the categories of the KIDSCREEN-10 are presented in the Table II. In relationship to the following questions: Have your parent(s) treated you fairly? and Have you felt full of energy? The schoolchildren with high nutritional levels reported the major proportion in very and extremely answers (p < 0.001). Instead, in relationship to the question: Have you felt sad? The schoolchildren with low nutritional levels presented the major proportion in very and extremely answers (p < 0.001).

Table II. Answer in relation with quality of life according nutritional level

The data shown represent n (%). p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Linear correlations (adjusted by sex) indicated that BMI was negatively correlated with food habits (r = 0.29, p < 0.0001) and HRQoL (r = -0.33, p < 0.05). Besides, children's food habits had a significant correlation with HRQoL (r = 0.48, p = 0.002) (Table III).

Table III. Linear correlation adjusts by sex between anthropometrics parameters and food habits and quality of life

The data shown represent r (p values). p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. BMI: body max index; WC: waist circumference; WtHR: waist-to-height ratio; BF: body fat.

The multivariable logistic regression reported associations between HRQoL, BMI (B = -0.41, 95% CI = -0.55, 0.93, p = 0.001), and food habits (B = -0.78, 95% CI = -0.09, -0.02, p = 0.002) (Table IV).

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to determinate the association between food habits (i.e., Mediterranean diet adherence), anthropometric parameters and HRQoL in Chilean schoolchildren. The main findings were: a) schoolchildren with high nutritional levels presented higher quality life than low and moderate nutritional level groups; and (b) BMI and food habits (i.e., Mediterranean diet adherence) reported associations with quality of life.

The schoolchildren with high nutritional levels reported higher HRQoL and they felt full of energy in comparison with moderate and low nutritional level groups. Instead, schoolchildren with low nutritional levels felt sad in greater proportion. A previous study has reported that food habits, such as adherence to the Mediterranean diet, presented positive correlations with different factors of mental wellness 8. Likewise, another investigation has reported that Japanese children with undesirable lifestyles, such as skipping breakfast, were more likely to have poor HRQoL, independent of sex, BMI, social background, and somatic symptoms 20.

Likewise, a study that evaluated the adherence to the Mediterranean diet with HRQoL in Portuguese adolescents reported that the adherence was positively associated with HRQoL 21. Moreover, a recent study carried out in Spanish children and adolescents concluded that adherence to the Mediterranean diet was found to behave as a protective factor for positive well-being in a cross-sectional analysis 22. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis reported that unhealthy dietary behaviour or lower diet quality was associated with decreased HRQoL among children and adolescents 23.

On the other hand, schoolchildren with high nutritional levels presented better anthropometric parameters. A previous study has reported that regular breakfast consumption is significantly associated with lower body fatness and healthier dietary habits 24. In the same line, a study carried out in Chilean schoolchildren reported that adherence to the Mediterranean diet was positively associated with a healthier lifestyle, mental wellness and physical fitness 8. Another study that examined the association between breakfast consumption and cardiovascular risk factors in European adolescents showed that adolescents who regularly consumed breakfast had lower body fat content, higher cardiorespiratory fitness and a healthier cardiovascular profile 25. Similarly, a study that evaluated the associations between habitual school day breakfast consumption, BMI, physical activity and cardiorespiratory fitness in children reported that habitual breakfast consumption was associated with healthy BMI and higher PA levels in schoolchildren 26.

In our sample, the multivariable logistic regression reported a negative association between BMI and HRQoL. In this line, n study that evaluated the relationships between HRQoL and BMI in children reported that physical, social and school functioning was significantly lower for obese children when compared with normal weight children 27. Likewise, a study showed that HRQoL was inversely related to the extent of obesity measured as either BMI or BF in children 28. Moreover, another investigation reported that the BMI was inversely correlated to adolescent self-reported HRQoL compared with normal weight adolescents 29. However, an investigation in elementary school girls reported no significant association between HRQoL and being overweight 30. In this line, BMI was not found to be a strong explanatory factor for variations in HRQoL in a Norwegian school sample; however, BMI was negatively associated with the HRQoL subscales of self-perception and physical well-being 31. A study examining HRQoL across weight categories in adolescents using both a general and a condition-specific measure reported that differences in HRQoL across weight categories differed based on the measure utilized. Clinicians should use caution when interpreting and comparing HRQoL findings 32. Childhood obesity can profoundly affect children's physical, social, and emotional well-being as well as self-esteem. It is also associated with a lower quality of life experienced by the child 33.

LIMITATIONS

The main limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design. As a result, causal relationships cannot be established. Despite this limitation, it is noteworthy that the information available regarding the association between HRQoL and children's food habits is important, especially for professionals in the Nutrition Sciences. So, the current study provides some insights into this field.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, children's food habits (i.e., Mediterranean diet adherence) and BMI were associated with HRQoL in Chilean schoolchildren; therefore, it is important to consider these results and develop different strategies in schoolchildren to improve their nutritional levels, as HRQoL represents a measure of happiness or satisfaction with life.