INTRODUCTION

The global cancer burden has grown significantly. Gynecological cancer is most prevalent among obese women living in developing countries and having low socioeconomic status. In Brazil, the expected number of new cases of this neoplasm for each year of the 2020-2022 triennium will be 16,710, with an estimated risk of 16.35 cases per 100,000 women (1).

Among risk factors for cancer inadequate lifestyles stand out, including smoking, high alcohol consumption, inadequate diet, obesity, and body fat, among other environmental factors (2-4). Obesity, a major global epidemic, is considered the most significant preventable risk factor for several types of malignant tumors among adult women; therefore, maintaining a healthy weight is a primary recommendation among cancer prevention entities (5). A study on the proportion of cancer cases attributed to lifestyle in Brazil found that 36.5 % of cervical cancers and 5.7 % of ovarian cancers in Brazil are attributed to an elevated body mass index (BMI) (6).

There are few studies in the literature assessing the nutritional status and body composition of women with gynecological tumors, especially before antineoplastic therapy. Gold-standard methods to estimate body composition in this population, such as magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, and DEXA, could be high-cost (12). Therefore, in the context of limited resources, the adoption of complementary indicators in determining nutritional status can be very useful.

Thus, the objectives of this study were: 1) to evaluate the nutritional status and body composition of women with gynecological tumors before starting cancer treatment; 2) to evaluate the fat mass index (FMI) as a complementary indicator for addressing the nutrition status.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

STUDY AND SAMPLE CHARACTERIZATION

This is a cross-sectional study with women recently diagnosed with gynecological tumors, between January and September 2017, at a public hospital in Brazil. The study included women with positive pathology for gynecological cancer (ICD 10 - C52, ICD 10 - C53, ICD 10 - C56, and other correspondents) (7,8), without any previous antineoplastic treatments, aged 20 years or more. Women with mental or cognitive deficits were excluded.

For the sociodemographic characterization we used the economic class according to the Brazilian Economic Classification criteria of the Brazilian Association of Research Companies (ABEP) (9). Clinical stage was classified according to the AJCC 8th edition (10). We collected self-reported diabetes mellitus (type 2) and arterial hypertension (11-13).

ASSESSMENT OF NUTRITIONAL STATUS AND BODY COMPOSITION

The following measures were considered: current weight (kg), height (m), body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) (14), arm circumference (AC, cm), tricipital skinfold (TS, mm), and arm muscle circumference (AMC, cm).

AC and TS measurements were determined according to the criteria established by Lohman et al. (15). We adopted the cutoff points proposed by Blackburn and Thornton (16). Nutritional status was also assessed using the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA), culturally adapted to Portuguese (Brazilian) by Campos and Prado (17), and classified according to Ottery (A: well-nourished; B: mildly/moderately malnourished; C: severely malnourished) (18).

We used the multi-frequency segmented bioimpedance analysis (InBody® model 230 equipment) to evaluate body composition. The fat mass index (FMI) was determined using the equation: FMI (kg/m2) = fat mass (kg) / height2 (m), and classified according to the cutoff points for women proposed by Kyle et al. (19). Of the 171 women who agreed to participated in the survey, 158 (92.4 %) underwent a bioelectrical impedance test.

We conducted a descriptive analysis of the data. Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) was used to estimate the correlation between FMI and conventional anthropometric variables. We considered a strong correlation for values higher than 0.70 (20). We adopted the significance level of p < 0.05. The analyses were conducted with the aid of the SPSS sotware, version 22.

This study followed the rules and guidelines of Good Clinical Practice according to Resolution 466/2012, and was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital under the protocol number: 2.042.767. We have no conflicts of interest to declare.

RESULTS

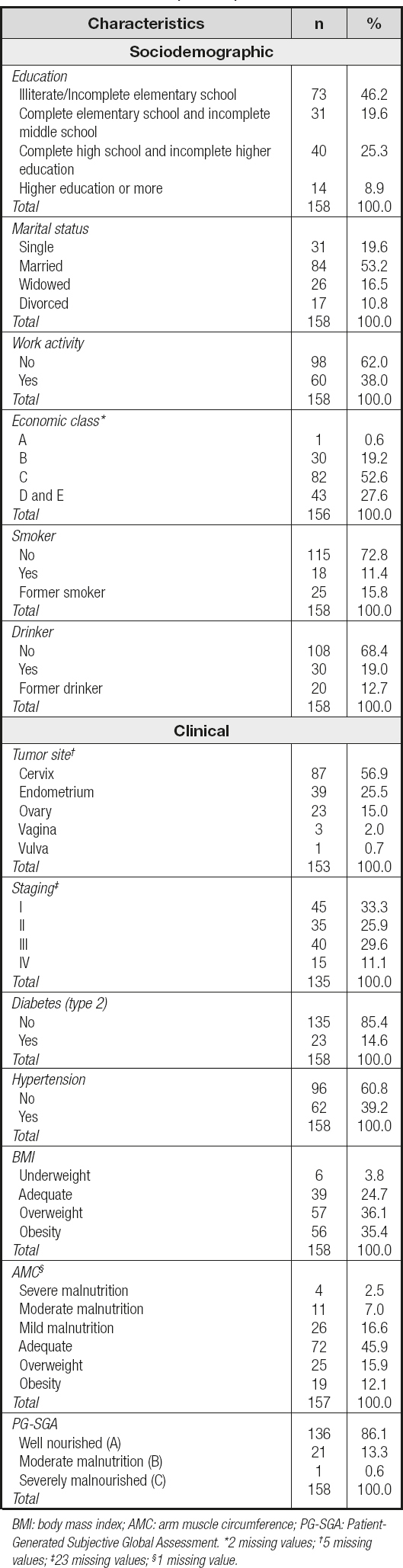

A total of 158 women recently diagnosed predominantly with cervical neoplasia (56.9 %) in a non-advanced stage (I and II, 59.2 %) participated in the study. The average age of the participants was 52.2 ± 15.3 years. Most were married (53.2 %), economic class C (52.6 %) (low economic level), non-smokers (72.8 %), non-alcoholic (68.4 %), and unemployed (62.0 %) (Table I).

Table I. Sociodemographic, clinical and nutritional status characterization of the participants

BMI: body mass index; AMC: arm muscle circumference; PG-SGA: Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment. *2 missing values; †5 missing values; ‡23 missing values; §1 missing value.

Regarding nutritional status, 45.9 % (n = 72) were adequate according to AMC, and well nourished (A) (86.1 %, n = 136) when assessed by the PG-SGA. As for BMI, most were overweight (71.5 %, n = 113) (Table I). The sample was composed, on average, by women with excess weight and high body fat (Table II).

The FMI showed a positive and significant correlation with BMI (r = 0.934), AC (r = 0.812), TS (r = 0.562) and AMC (r = 0.747), p < 0.001 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Correlation between fat mass index (FMI) and conventional anthropometric variables (FMI: fat mass index; BMI: body mass index; AC: arm circumference; TS: triceps skinfold; AMC: arm muscle circumference).

We identified that women with a very high FMI belonged to the groups with illiterate/incomplete elementary schooling (52.4 %), no work activity (73.0 %), a low economic class (C, 57.4 %), obesity (BMI) (85.7 %) and well nourished (95.2 %) (Table III).

Table III. Classification of the Fat Mass Index (FMI) of the participants considering the sociodemographic, clinical, and nutritional status characteristics

BMI: body mass index; AMC: arm muscle circumference; PG-SGA: Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment. *2 missing values; †5 missing values; ‡23 missing values; ¦1 missing value.

DISCUSSION

This study investigated the nutritional status and body composition of women diagnosed with gynecological tumors without previous antineoplastic treatment, and evaluated their FMI as a complementary indicator for addressing the nutrition status.

In this study, cervical cancer was predominant, corroborating both national and international statistics pointing at it as the most frequent gynecological tumor in the female population (1).

The women in this study were overweight and had high body fat at diagnosis. Although excess body fat and lifelong weight gain can influence the development of some gynecological cancers through inflammatory, metabolic, and hormonal mechanisms (21), its influence on cervical cancer risk has been poorly understood.

Excess body fat can negatively influence treatment and patient quality of life. Patients with morbid obesity and endometrial cancer or ovarian cancer submitted to surgery had a higher number of surgical complications than patients with a BMI < 40.0 kg/m2 (22,23). Similarly, a study on the impact of obesity on complications and survival in 2,500 patients with endometrial cancer found that obese women had a higher risk of all-cause mortality (24).

In addition to the impact on performing an adequate and safe surgery, excess body fat can compromise a safe and effective administration of cytotoxic agents. There are limited data on the evaluation of the relationship between obesity and the pharmacokinetics of chemotherapy, specifically regarding volume, in obese patients. The issue of reassessing chemotherapy doses based on body composition in this population should be discussed (25).

The FMI showed a strong and positive correlation with conventional anthropometric measurements such as BMI, AC, and AMC, and a moderate and positive correlation with TS; thus, it can be considered a good indicator for assessing body composition at diagnosis, besides using the lean body mass index. The isolated use of BMI does not reflect body composition in a cancer patient and, therefore, should always be used with other body composition measures (26).

In the present study, most women with a very high FMI were obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2) and had a low economic and educational level. Similarly, in a study that estimated the frequency and sociodemographic distribution of risk and protective factors for chronic diseases in Brazil (27), the frequency of overweight and obesity among women decreased notably with increased education.

This study has some limitations. The study was developed in only one oncology hospital, and its cross-sectional design limits the evaluation of causal relationships. We did not evaluate weight loss or weight gain before the assessment, which could influence body composition. In addition, no data were collected that could validate the FMI measurement as a predictor of complications and other clinical outcomes since that was not the objective of the present study. It is important to point out that it would be interesting to evaluate whether the patients were menopausal or premenopausal, since fat mass is associated with an increased risk of uterine corpus cancer in postmenopausal women (28). We believe that our results may arouse interest in conducting new studies with prospective follow-up, given the importance of nutritional intervention at diagnosis and the implications of overweight in cancer treatment.

CONCLUSION

Women recently diagnosed with malignant gynecological tumors without previous antineoplastic treatments were admitted with overweight and increased FMI.

Besides, FMI showed a good correlation with conventional measures of BMI, AC, and AMC. Thus, FMI may be a good indicator of body composition and a potentially useful tool to complement the assessment of nutritional status. In clinical practice, FMI can help multidisciplinary teams to perform early clinical and nutritional interventions.