INTRODUCTION

The pandemic of physical inactivity is linked with several chronic diseases and premature deaths (1). The World Health Organization guidelines for adults include strong recommendations based on overall moderate-certainty evidence on weekly volumes of aerobic and muscle-strengthening physical activity (PA) and also, it reaffirms that all adults should regularly engage in PA and that some PA is better than none (2). Insufficient activity is a serious health concern, especially among university students (3). Similarly, studies have shown that PA decline is evident during young adults' transition into early adulthood with the steepest decline occurring at the time of entering a university (4,5).

Amongst dietary patterns, Mediterranean diet (MD) is well known as one of the healthiest (6). The main characteristics of this diet are a high consumption of plant products (fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts), bread and other cereals (wheat being an optional food), olive oil as the main fat, vinegar, and wine consumption in moderate quantities (7). Scientific evidence has demonstrated an inverse association of MD with non-communicable diseases (e.g., cancer, cardiovascular diseases, hypertension or metabolic syndrome) (8) as well as with mortality (9), with some of the dietary components mentioned above being the main influences on these relationships (9).

On the other hand, unhealthy diet and insufficient PA have shown a tendency of clustering among Spanish university students (10-13). Moreover, although there are studies that have evaluated the association between PA and MD in university students (10), studies assessing the specific Mediterranean pattern factors associated with PA levels among university students are scarce. Supporting this notion, one systematic review of controlled trials among university students concluded that missing information about intervention components limits the strength of conclusions about the most effective strategies and the evidence of effectiveness, highlighting the need for further high-quality studies (14). Furthermore, another systematic review showed that nutrition education, enhancing self-regulation factors towards dietary intake, and point-of-purchase messaging strategies may improve university or college students' dietary intake. Based on the above, knowing the dietary factors associated with a higher level of physical activity might help to design more accurate and effective interventions. Thus, the aim of the present study was to assess the level of PA and its association with Mediterranean dietary patterns in university students of health sciences at Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha (Spain).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

PARTICIPANTS AND STUDY DESIGN

A cross-sectional study was performed through an online survey among university students of health sciences of Castilla-La Mancha (Spain). The prevalence of sufficient PA levels in university students was estimated at 20 % (15), a total width of the confidence interval of 0.10 and a confidence of 95 % (16). Under these conditions, the minimum number of subjects required is 523. Regarding inclusion criteria, only university students who signed the informed consent were enrolled. Contrariwise, regarding exclusion criteria, the following were excluded: a) participants with any kind of dysfunction that restricted practicing PA (i.e., any disease or motor problem); and b) participants under some kind of pharmacological treatment.

This research was approved by the Board of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Castilla-La Mancha (date: April 15, 2020). Also, it was performed following the Helsinki Declaration and respecting the human rights of all study participants. All participants voluntarily agreed to participate in the study.

Of the original 575 participants, 20 participants were excluded due to missing data. Thus, 555 participants completed the survey (78.2 % females). The differences in terms of gender are justified by the higher prevalence of women in health sciences university degrees, with an approximate proportion of 70 % of females and 30 % of males in Spain.

The study was carried out from May 2020 (first dispatch of the on-line survey) to July of the same year. An initial data collection survey was designed that contained demographic data on the participants on the one hand and, on the other, a survey was carried out with the collection of data on level of PA and adherence to the MD. The data collected in the Google Forms survey was stored in Google Sheets (https://www.google.com/sheets/about/) (password-protected, encrypted and de-identified) for subsequent export and processing. The “Google Sheets + Mailchimp Integrations” plugin (https://zapier.com/apps/google-sheets/integrations/mailchimp), the Zapier automation platform (https://zapier.com/how-it-works), and the Mailchimp platform (https://mailchimp.com/why-mailchimp/) were used to store the database.

PROCEDURES

Adherence to the Mediterranean diet

Adherence to MD was assessed using the 14-item Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener (MEDAS), validated in the Prevention with MEDiterranean DIET (PREDIMED) trial (17). To obtain the global about adherence to MD, a value of +1 was assigned to each condition met, and a value of 0 when the condition was not meet. The final PREDIMED score ranged from 0 to 14.

Level of physical activity (PA)

To measure PA, the Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity Scale (RAPA) (18) questionnaire was used, which is an instrument that assesses any PA performed, and has administration times that are acceptable for use in clinical settings. This test was chosen owing to its simplicity and ease of completion. RAPA is divided into two categories: RAPA 1, which determines the level of PA: a - sedentary ('I rarely or never do any physical activities'), b - little active ('I do some light or moderate PA, but not every week' or 'I do some light PA every week'), c - moderately active ('I do moderate PA every week, but less than 30 minutes a day or 5 days a week' or 'I do vigorous physical activities every week, but less than 20 minutes a day or 3 days a week'), and d - active ('I do 30 minutes or more a day of moderate PA, 5 or more days a week' or 'I do 20 minutes or more a day of vigorous PA, 3 or more days a week'); and RAPA 2, which assess the type of exercise: a - none muscle strength and flexibility activities, b - muscle strength activities ('I do activities to increase muscle strength, such as lifting weights or calisthenics, once a week or more', c - flexibility activities ('I do activities to improve flexibility, such as stretching or yoga, once a week or more'), or d - both muscle strength and flexibility activities). For further analyses, participants were divided into two groups according to their RAPA 1 score: 'insufficiently active' (“sedentary” + ”little active”) (score 1-3) and 'sufficiently active' (“moderately active” + ”active”) (score 4-7). Similarly, the RAPA 2 score was used to categorize two different groups: 'strength and flexibility activities' (both muscle strength and flexibility activities) and 'neither muscle strength nor flexibility activities'.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The statistical analysis was carried out by the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) v.24 for Windows. From the computer platform used to collect the necessary data for the present study, the variables were ordered, coded and refined to be able to be analyzed. The quantitative variables have been reported as mean and standard deviation; while qualitative variables such as absolute and relative frequencies. The relationship between the qualitative variables was performed using the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test in the case of an expected frequency lower than 5. Finally, a binary logistic regression analysis was performed considering the practice of PA as a dependent variable and the different Mediterranean dietary patterns as independent variables, through backward stepwise regression. No statistically significant interaction was found for gender and MD in relation with the level of sufficient PA (p = 0.973) and the engagement in strength and flexibility activities (p = 0.177). Thus, we analyzed males and females together to increase the statistical power. Age, gender and faculty in which he/she was enrolled were included as covariates. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

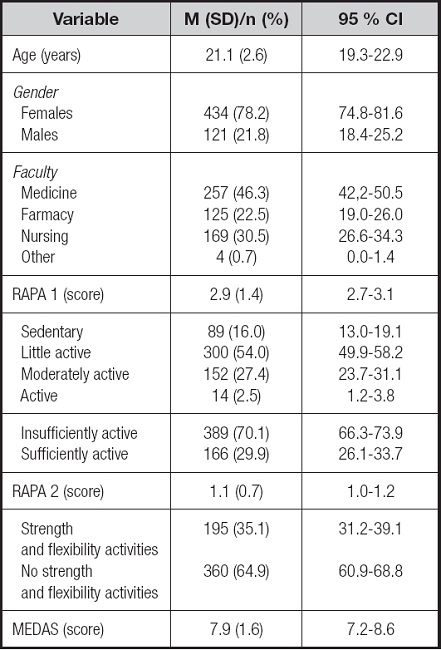

Table I shows the characteristics of the study participants. The mean age of the analyzed sample was 21.1 (SD = 2.6) years. Also, the proportion of females (78.2 %) was higher than that of males (21.8 %). As regards PA, 2.5 % of the participants were considered active (29.9 % were considered sufficiently active) and 35.1 % did both strength and flexibility exercise. The mean MEDAS score was 7.9 (SD = 1.6).

Table I. Characteristics of the participants in the study (n = 555)

MEDAS: Mediterranean Diet Adherence Screener; RAPA: Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity. RAPA 1: Assessment of aerobic activities; RAPA 2: Assessment of strength and flexibility activities.

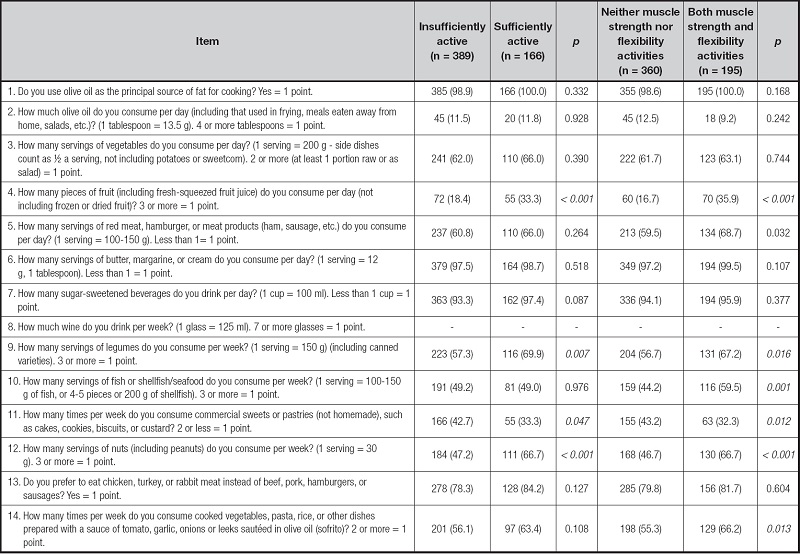

Table II indicates the associations between Mediterranean dietary factors and the different established groups of PA. A significant association for fruits, legumes, sweets/pastries and nuts was found for both PA groups (p < 0.05 for all). Moreover, an association was observed for red meat, fish/seafood and sofrito in those who engaged in both strength and flexibility activities (p < 0.05 for all).

Table II. Association between Mediterranean dietary factors and different physical activity established groups

Data expressed as number (percentage). Italics indicates a statistically significant association (p < 0.05).

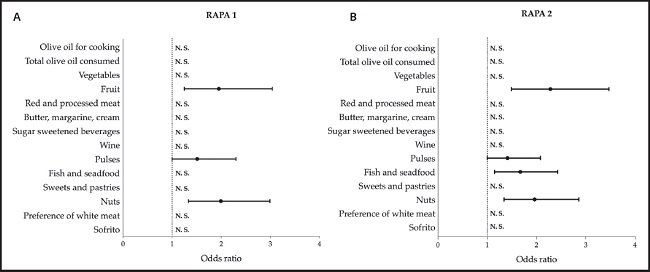

Figure 1 indicates the final results of the binary logistic regression analyses, after adjustment for potential confounders. A greater association was observed between the intake of fruits (OR = 1.95; 95 % CI, 1.25-3.04), pulses (OR = 1.51; 95 % CI, 1.00-3.20) and nuts (OR = 1.99; 95 % CI, 1.33-2.99) in those considered sufficiently active. Similarly, we found a significant relationship between the intake of fruits (OR = 2.28; 95 % CI, 1.49-3.47), pulses (OR = 1.41; 95 % CI, 1.00-2.08), nuts (OR = 1.96; 95 % CI, 1.34-2.86), and fish/seafood (OR = 1.67; 95 % CI, 1.15-2.43) in those who engaged in both strength and flexibility activities.

Figure 1. Binary logistic regression analysis with Mediterranean dietary patterns as independent variables and sufficient physical activity or engagement in both strength and flexibility activities as dependent variables. Data expressed as odds ratio (OR) and 95 % confident intervals. Insufficiently active and no engagement in both strength and flexibility activities selected as reference groups. Adjusted by age, gender and type of faculty. A: assessment of aerobic activities; B: assessment of strength and flexibility activities. RAPA: Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity

DISCUSSION

The current study aimed to evaluate the level of PA and its association with specific Mediterranean dietary patterns in a sample of Spanish university students of health sciences. In this sense, only three out of 10 participants were considered sufficiently active and reported to do both strength and flexibility exercises. Similarly, some Mediterranean dietary patterns were identified as correlates of higher physical activity level.

Our finding matches those of previous studies in the scientific literature, which indicate insufficient levels of PA among university students (4,15,19,20). As per the factors affecting the decline of PA levels during this life stage, they include changes in psychosocial aspects and residency (i.e., distance to the university (21) and greater time demands, such as work and class time (22). Supporting this notion, one study indicated some barriers for PA among university students such as lack of time because of busy lesson schedule or due to responsibilities associated with family and social environment, or even the priority of parents on academic success over PA (23). Similarly, another study in Spanish university students reported as reasons for not performing PA time availability, lack of time and interest in PA (mainly in performance and/or body esthetics) (24). In addition, another possible hypothesis about these low levels of PA might be related to autonomous regulations (especially integrated regulation), which have been linked to higher PA levels (25). However, these abovementioned variables (i.e., barriers and motives for PA, self-regulation) were not assessed in the present study.

Another finding of our study is that we found a significant relationship between engagement in PA and Mediterranean dietary patterns, coinciding with other studies found (26-28). In the same line, a higher intake of some healthy Mediterranean patterns (e.g., fruits or nuts) was observed in those who were considered sufficiently active and among those who engaged in both strength and flexibility activities. Our findings match those obtained by Mieziene et al. (28) in Lithuanian young adults, which showed that lower levels of PA were likely related to underconsumption of olive oil, nuts, fish, seafood, legumes and wine, as well as red meat. Similarly, the intake of some specific foods (e.g., nuts) has been related to higher cardiorespiratory fitness (via unsaturated fatty acids) (29). This fact has been also reported among Spanish university students and, as the authors recognize, PA could (at least partially) explain this relationship (30). Also, two studies performed among Spanish university students showed direct significant associations between PA and the intake of some healthy foods (e.g., fruits (31,32) and legumes (31). Accordingly, being more physically active could motivate individuals to make healthy food choices (33) (e.g., adherence to MD) and provide their organism with the necessary nutrients (carbohydrates, vitamins, healthy fats or quality proteins). Some factors could explain these findings. First, health sciences students may have a low quality of life and experience greater difficulties due to hospital shifts, high study load, stress, and general burnout (34). Therefore, health care students are at risk of adopting an unhealthy lifestyle, including excessive alcohol consumption, smoking, and unhealthy dietary patterns, with overconsumption of comfort foods, which are commonly used as copying mechanisms for chronic psychological distress (35). Second, the regular practice of PA increases energy expenditure, which leads to an increase in calorie consumption, which could facilitate a more varied diet and provide greater nutritional quality (36). Third, the association between fruit consumption and PA could be due to some vitamins present in fruits (e.g., vitamin C) (37). Higher consumption of fruits could provide greater levels of vitamin C, which might help reduce the damage caused by free radicals, preventing injuries and improving physical performance (38). Thus, the high levels of vitamin C found in physically active individuals can be explained by their high intake of fruit and vegetables. Also, increased PA and higher adherence to MD have been linked to increased total antioxidant capacity (39). Fourth, the association between nuts and PA could be due to their content in omega-3 fatty acids, which have potential anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity that may provide health benefits and improve performance, especially in those who practice PA, due to their increased production of reactive oxygen (40). Lastly, the relationship between some protein-rich foods (e.g., legumes or nuts) and higher levels of PA could be due to the influence of exercise on protein concentrations (41). Thus, plasma protein concentrations have been shown to be responsible for regulating fuel storage (42), energy (43), and force production (44).

Certain limitations should be indicated in this study. On the one hand, due to the cross-sectional design, it cannot be concluded that the observed relationships reflect causal relationships. Furthermore, self-reported measures were used in this study to assess both PA and adherence to MD. Another limitation found is the fact that only university students from health sciences degrees were evaluated. Thus, the results could be different for degrees in other areas. In this sense, eating habits and lifestyle among health sciences university students seems to be healthier than in students from other areas of knowledge (12). On the contrary, with regard to the strengths of our study, as far as we know it is one of the first studies to analyze the specific Mediterranean dietary patterns related to the practice of PA in university students.

CONCLUSIONS

This study suggests that the consumption of certain Mediterranean food patterns was associated with sufficient levels of PA in the sample of Spanish university students analyzed. Our results highlight the need to promote a healthy lifestyle in university students through specific intervention programs. In this sense, universities should be concerned about encouraging and facilitating PA and healthy eating habits in university students.