INTRODUCTION

The lifestyle of the population is highly associated with the current increase in the prevalence of cardiometabolic disease (i.e., diseases that compromise both cardiovascular and metabolic systems) in young and adult populations, including arterial hypertension (HTN) (1) and diabetes (2). Physical activity (PA) and healthy nutrition are key environmental factors to preserve good cardiometabolic health in adolescents and adults (3-5). On the other hand, sleep hygiene (i.e., sleeping a sufficient amount of hours per each 24 h cycle) (6,7), and avoiding tobacco and alcohol consumption have been described additionally as important modifiable risk factors contributors to HTN and diabetes in adolescents and adults (8). More recently, it was reported a 26.9 % of HTN prevalence, and 11.2 % prevalence of diabetes in the non-ethnic Latin American adult population (1). On the other hand, ethnic young cohorts have shown recently a worrying 35.9 % prevalence of HTN in comparison with their non-ethnic peers (11.6 %) (9).

Following this, and as a relevant component of a healthy lifestyle, PA practice at different ‘intensities' (i.e., vigorous, moderate, or low) has been associated with lower cardiovascular risk in young (9) and adult populations (10,11), but also with better physical fitness (10,12). Additionally, fruit and vegetable intake frequency (i.e., healthy nutrition) as well as water consumption is also a key modifiable element in avoiding HTN and diabetes in adolescents and adult Latin American populations (13). In this sense, although there is important evidence in the Chilean population about lifestyle and its relationship with cardiometabolic disease markers of HTN (i.e., systolic [SBP], diastolic [DBP] blood pressure), and diabetes (fasting glycemia [GL]) in both adolescents and adults, there is a scarcity of evidence about these markers in the population of ethnic Latin American groups such as the Mapuche —people of the land in the Mapudungun language— and Aymara —the language of many years in the Jayamararu language. From a demographic perspective of the national Chilean survey, there are around 2,185,729 individuals in the Chilean population who declare themselves to be of some native ethnic group, this amount representing 12.8 % of the total Chilean population. Of this percentage (i.e., 12.8 %), 79.8 % correspond to Mapuche, and 7.2 % to Aymara ethnicity, among others (14), both being the major representatives of ethnicity in the country. Along this line, previous studies have suggested a worrying increase in insulin resistance in the adult Mapuche population (15), and other reports have shown higher levels of blood pressure (16), and fasting glucose (17), thus increasing the risk of HTN and diabetes. Epidemiologically, preliminary studies have described that adults of Mapuche ethnic origin in Chile report a 24.5 % of HTN prevalence (18), while 18.5 % was described for the Aymara ethnic group (19). Other reports describe the diabetes prevalence in Mapuche ethnicity as 8.2 %, and 6.9 % for Aymara (17). On the other hand, despite lifestyle factors such as PA and nutrition and their known association with HTN and diabetes markers, other evidence has suggested that ethnic groups who are living in urban areas show a major cardiometabolic risk in comparison with their rural peers, with living in urban areas being attributed a greater role than lifestyle factors for these diseases (15); it is of great interest to study these groups in terms of increasing health prevention strategies.

Unfortunately, these previous studies are isolated, have been developed in one or another of the 15 geographic regions of Chile, and do not contain major representative data of the whole country. Thus, there is a scarcity of studies reporting a representative sample of these groups (i.e., at least from a geographical perspective) including ethnic adolescents and adult populations such as the Mapuche and Aymara groups, describing lifestyle (i.e., PA ‘intensity', nutritional, water consumption, sleep hygiene, tobacco, and alcohol habits), and testing their association with HTN and diabetes markers. Thus, the primary aim of this study was to describe the lifestyle and cardiometabolic risk factors for arterial hypertension (HTN) and diabetes in ethnic Latin American Mapuche, Aymara, and other non-ethnic Chilean individuals > 15 years of age. A secondary study was to determine the association between physical activity intensity with HTN and diabetes markers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

STUDY DESIGN

A cross-sectional national secondary study was developed with the National Health database surveys (NHS) 2016-2017 of Chile. The NHS is a prevalence, and multi-stage national study that includes representatives of the Chilean geographical country, and is applied in multi-stages, in person at home with families using a cross-sectional random, stratified-by-conglomerates survey with inclusion of the population ≥ 15 years old, with or without an ethnic origin, and living in particular homes, from urban to rural areas of the 15 geographical regions of this country.

Of 6,233 thousand participants included in the NHS 2016-2017 (i.e., all of this population are part of the Chilean public health system), a total of n = 731 participants belonged in some of the major eight ethnic groups, including Aymara n = 151, Rapa-Nui n = 1, Quechua n = 14, Mapuche n = 466, Atacameño Linkánanta n = 36, Coya n = 17, Kawésqar Alacalufes n = 3, and Diaguita n = 43), with the rest of participants being identified as a non-ethnic adolescent (≥ 15 years)/adult population (n = 5.502) ascribed to the Chilean public health system. The present study included and analyzed the information related only to the Mapuche ethnic gro- up (EG-Map; men n = 166, women n = 300), Aymara ethnic group (EG-Aym; men n = 55, women n = 96), and the population of non-ethnic origin (No-EG; men n = 2,057, women n = 3,445). The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Escuela de Medicina de la Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile (16-019), and all participants signed an informed consent (20).

LIFESTYLE PARAMETERS

Characterization of physical activity and sedentary time

To determine PA levels, the "Global Physical Activity Questionnaire" version 2 was applied (GPAQ v2) (20). Thus, PA was described according to its intensity as follows; i) PA of ‘vigorous'-intensity (PAVI); ii) PA of ‘moderate'-intensity (PAMI), and finally iii) PA of ‘light'-intensity (PALI), which corresponded to all those activities such as walking, transport, or cycling.

Determination of nutrition frequency

The NHS 2016-2017 includes the GABA criteria as follows; i) fish consumption 2 times/week (fish and seafood), ii) dairy products in 3 servings/day (milk, cheese, or yogurt), iii) legumes consumption 2 times/week (legumes/beans), iv) consumption of fruits/vegetables 5 servings/day, and finally vi) drinking water 6 glasses/day (21). This information was obtained from the three Mapuche, Aymara, and non-ethnic adult groups by self-report.

Determination of sleep hygiene, tobacco habit, and alcohol consumption

Other lifestyle parameters were registered and reported as sleep time using the following categorization; sleep hygiene (< 7 h/day; 7 to 9 h/day; and > 9 h/day), tobacco (Yes, 1 or more cigarette/day; Yes, occasionally, < 1 cigarette/day; No, I stopped smoking; and No, I have never smoked), and alcohol consumption (Never; ≤ 1 cups/week; 2 to 3 cups/week; and ≥ 4 cups/week).

All information on nutrition frequency, sleep hygiene, tobacco habit, and alcohol consumption was obtained by self-report, using the validated questionnaire of the Chilean NHS 2016-2017.

Measurement of blood pressure (main outcome)

As HTN markers, SBP and DBP were measured in both arms twice during 30 sec, and in different days (at least 1 day between measurements) by the professional nursing staff of the public health center. In this study, these measurements were averaged and registered for subsequent analyses. After that, both SBP/DBP values were used to classify HTN prevalence in % considering categories of ‘normotension, elevated blood pressure, HTN stage 1 (SBP ≥ 140, or PAD ≥ 90 mmHg), and HTN stage 2, following standard current procedures (22).

Measurement of fasting glycemia (main outcome), and lipid profile outcomes

As diabetes marker, fasting plasma glucose (GL) was used. This outcome was measured in conditions of at least 8 hrs of fasting state and applied similarly to previous studies (21), following the Chilean clinical guide (23).

Additionally, we also included the metabolic markers of dyslipidemia (total cholesterol (Tc), low-density lipid cholesterol (LDL-c), high-density lipid cholesterol (HDL-c), and plasma triglycerides (Tg) as additional information. As categorical information, we also included the metabolic syndrome diagnoses.

Anthropometric measurements

To assess the body weight, there was used a digital scale OMRON® (model HN 289 OMRON Corporation, Kioto, Japon) with a sensitivity of 100 g, and a maximum weight register of 150 kg). Height was measured by a metal tape, a square, and adhesive tape (i.e., to secure in a wall or gate). Waist circumference was measured using inextensible and flexible tape. The nutritional state was established by body mass index (BMI) following adult recommendations as follows; underweight < 18.5 kg/m2; normal weight: 18.5-24.9 kg/m2; overweight: 25.0-29.9 kg/m2 and ≥ 30.0 kg/m2 to obesity. There was also included information regarding the nutritional state, (underweight, normal weight, overweight, obesity) (24).

STATISTICAL ANALYSES

Data of socio-demographic and cardiometabolic characteristics are shown as means (95 % confidence interval [CI]) for continuous variables, and numbers (proportion, %) for categorical variables. To continuous outcomes, the univariate test was applied to establish the significance of interaction by groups and to compare the difference between groups, Sidak's post-hoc was used to compare both ethnic EG-Map and EG-Aym versus the non-ethnic group. Age, BMI, sex, height, and region were used as co-variables for continuous outcomes. For categorical outcomes Pearson's Chi-squared test was applied to determine differences in frequencies, and Somer's d-test. Additionally, the association between lifestyle factors of PA ‘intensity', as well as the nutrition, sleep hygiene, and other secondary outcomes were associated with SBP, DBP, and GL using linear regression analyses by 4-models; model 1 (PALI, PAMI, PAVI, min/day), model 2 (seafood consumption, dairy products, whole grains, legumes, greens and vegetables, and water consumption), model 3 (sleep time in the week, and the weekends), and model 4 (tobacco and alcohol habits). These analyses were applied independently to describe PA ‘intensity', nutrition, sleep hygiene, tobacco, and alcohol consumption predictive weight. All analyses were carried out using the SPSS version 28 software. All procedures described were developed following the technical recommendations of the Guideline of Application F2 of the NHS 2016-2017 (25).

RESULTS

COMPARISON OF DESCRIPTIVE DATA ACCORDING TO GROUPS

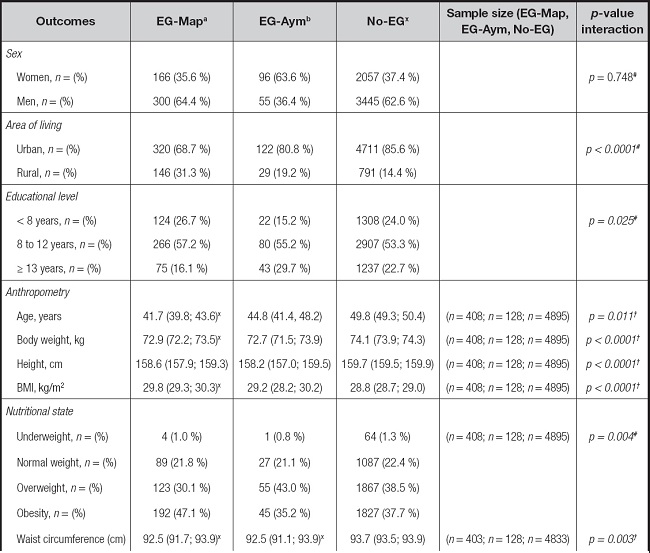

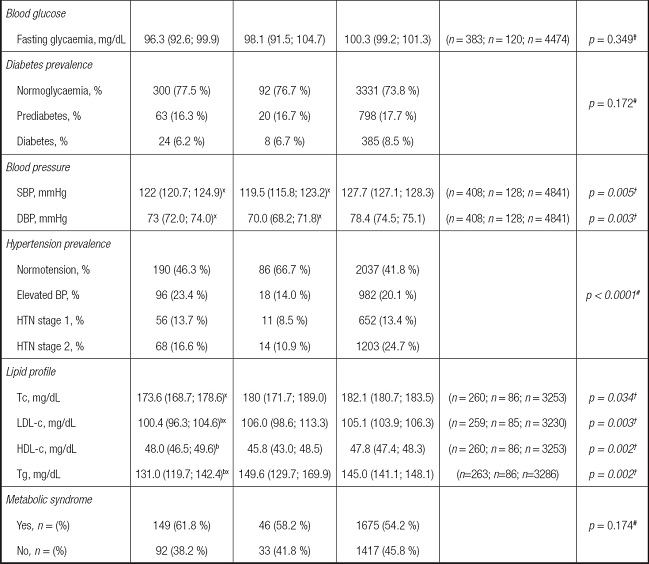

The characteristics of the Mapuche, Aymara, and non-ethnic groups are shown in table I. For continuous outcomes, there were significantly different values of age, body weight, height, BMI, waist circumference, fasting glycemia, SBP/DBP, Tc, LDL-c, HDL-c, and Tg between EG-Map, and EG-Aym versus (vs.) the No-EG group (Table I). For categorical outcomes, there were significant differences in the area of living (urban, rural), educational level, and nutritional state in EG-Map, and EG-Aym vs. No-EG (Table I).

Table I. Descriptive characteristics of the > 15-year-old Chilean population of ethnic Mapuche, Aymara, and non-ethnic peers from the National Health Survey 2016-2017.

Table I (cont.). Descriptive characteristics of the > 15-year-old Chilean population of ethnic Mapuche, Aymara, and non-ethnic peers from the National Health Survey 2016-2017.

Data are shown as means and 95 % confidence intervals (95 % CI) for continuous outcomes and as number (n) and percentages (%) for categorical outcomes.

Groups are described as: EG-Map: Mapuche ethnic group; EG-Aym: Aymara ethnic group; No-EG: no ethnic group. Outcomes are described as: BMI: body mass index; SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; Tc: total cholesterol; LDL-c: low-density lipid cholesterol; HDL-c: high-density lipid cholesterol; Tg: triglycerides.

†Data analyzed by univariate test. aSignificantly different versus EG-Map at p < 0.05, bSignificantly different versus EG-Aym at p < 0.05. xSignificantly different versus No-EG at p < 0.05 by Sidak's post-hoc.

#Categorical data analyzed by Pearson's Chi-squared test at p < 0.05. Italics values denote significant between-group interaction at p < 0.05.

DESCRIPTION AND COMPARISON OF LIFESTYLE DATA ACCORDING TO GROUPS

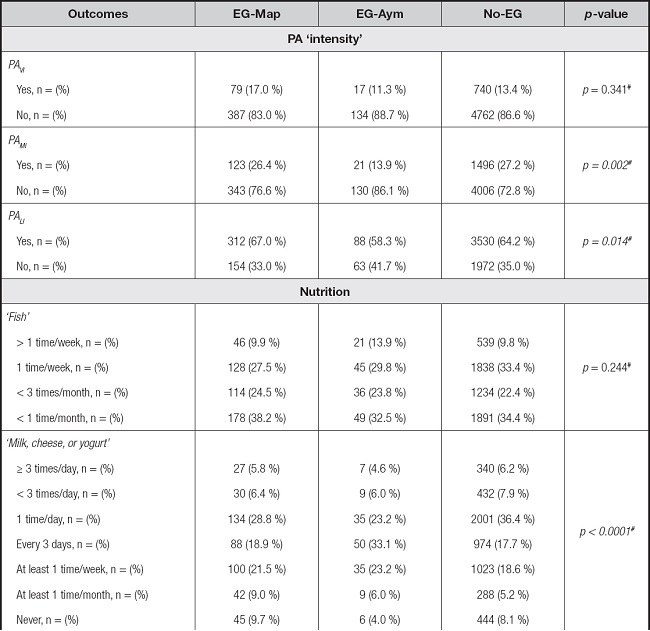

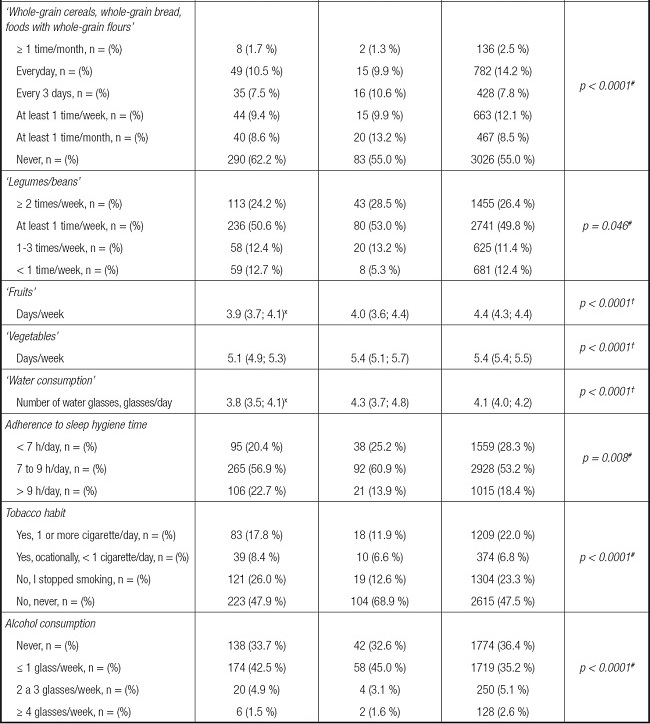

In the characteristics of the PA ‘intensity' (measured by the GPAQ-v2 questionnaire), there were significant differences among groups in the PAVI, PAMI (Table II). In the nutritional parameters, there were significant differences in the frequency of ‘milk, cheese, or yogurt', ‘whole grains, bread, foods with whole-meal flours', ‘legumes/beans', ‘fruits' and ‘vegetables', as well as in ‘water consumption' (Table II). There were significant differences in the sleep hygiene (hours of sleep on weekends, the adherence to sleep hygiene, and tobacco habit and alcohol consumption between EG-Map, and EG-Aym versus No-EG (Table II).

Table II. Lifestyle parameters (physical activity, diet, water consumption, sedentary time, sleep hygiene, and tobacco/alcohol habits in the Chilean > 15-year-old population of ethnic Mapuche, Aymara, and non-ethnic peers from the National Health Survey 2016-2017.

Table II (cont.). Lifestyle parameters (physical activity, diet, water consumption, sedentary time, sleep hygiene, and tobacco/alcohol habits in the Chilean > 15-year-old population of ethnic Mapuche, Aymara, and non-ethnic peers from the National Health Survey 2016-2017.

Data are shown as number (n) and percentage (%).

Groups are described as: EG-Map: Mapuche ethnic group; EG-Aym: Aymara ethnic group; No-EG: No-ethnic group. Outcomes are described as: PAVI: physical activity of vigorous intensity; PAMI: physical activity of moderate intensity; PALI: physical activity of light intensity.

#Denotes categorical data analysed by Pearson's Chi square test at p < 0.05. Italics values denote significant between-group interaction at p < 0.05.

†Analysed by univariate test at p < 0.05. Italics values denote significant between-group interaction at p < 0.05.

ASSOCIATION OF PA ‘INTENSITY' WITH HTN AND DIABETES OUTCOMES

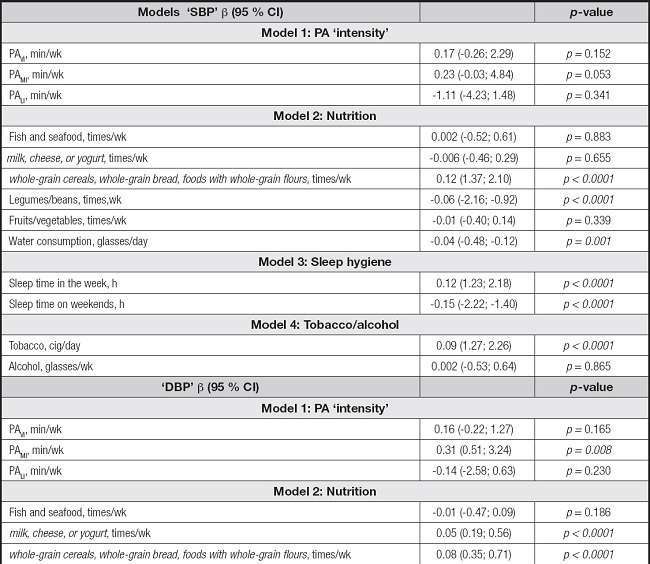

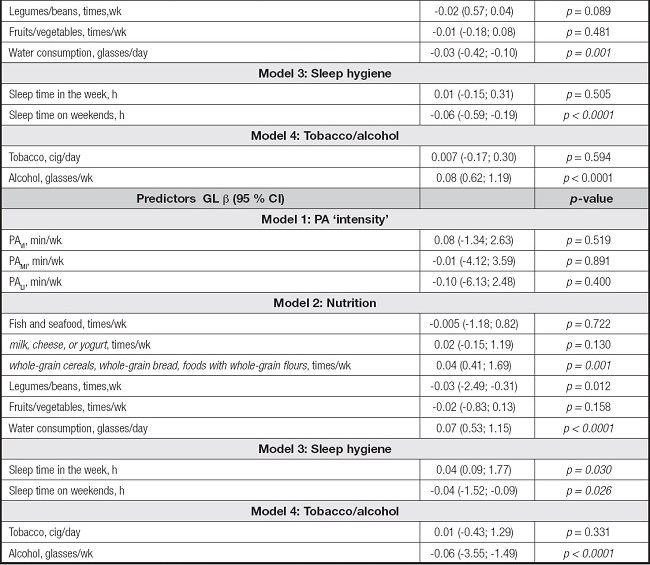

For predicting blood pressure from PA ‘intensity', lineal regression analyses revealed only PA of ‘moderate' intensity predicted significantly DBP in model 1 (PAMI, p = 0.008) (Table III). The diabetes marker of GL was significantly associated with model 2 (nutrition 0.9 %, p < 0.0001), and model 4 (tobacco and alcohol habits 0.6 %, p < 0.0001). In another lifestyle, SBP has significantly associated with model 2 nutrition (whole grains, water consumption), model 3 sleep hygiene, and model 4 tobacco, all p < 0.001), DBP was significantly associated with model 2 nutrition (whole-grains, legumes, and water consumption), model 3 sleep hygiene (sleep time in the week, and weekends), and model 4 tobacco, all p < 0.001) (Table III). Fasting plasma glucose was significantly associated with model 2 nutrition (whole-grain, water consumption, p < 0.001), model 3 sleep hygiene (sleep time on weekends, p = 0.026), and model 4 alcohol habits, p < 0.0001) (Table III).

Table III. Association of four models of lifestyle outcomes with hypertension and diabetes markers (SBP, DBP, and GL) in Chileans of ethnic Mapuche, Aymara, or non-ethnic background > 15 years old, from the National Chilean Health Survey 2016-2017.

Table III (cont.). Association of four models of lifestyle outcomes with hypertension and diabetes markers (SBP, DBP, and GL) in Chileans of ethnic Mapuche, Aymara, or non-ethnic background > 15 years old, from the National Chilean Health Survey 2016-2017.

Data are shown as beta coefficient and 95 % CI. All analyses were adjusted by age, BMI, sex, height, and region. PAVI: physical activity of vigorous intensity; PAMI: physical activity of moderate intensity; PALI: physical activity of light intensity. Italics values denote a significant association between the independent outcome and the dependent outcome at p < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

The primary aim was to describe the lifestyle and cardiometabolic risk factors for HTN and diabetes in ethnic Latin American Mapuche, Aymara, and other non-ethnic > 15-year-old Chilean adolescents/adults. A secondary study was to determine the association between physical activity ‘intensity' with HTN and diabetes markers. The main finding of this study related to the first aim is that; i) there are significant differences in some anthropometric, nutritional state, waist circumference, blood pressure, and lipid profile outcomes between EG-Map and EG-Aym in comparison with peers of No-EG, ii) being also significantly different the practice of different PA intensities, as PA of ‘moderate', and ‘light' intensity among groups, and to the second study aim concerns, iii) DBP was significantly associated with PA of ‘moderate' intensity. These results were displayed with other lifestyle outcomes associated with SBP such as nutrition, sleep hygiene, and tobacco, or by contrast, DBP was also associated with nutrition, and sleep hygiene, and finally, GL was significantly associated with nutrition, and sleep hygiene and alcohol. Overall, there was a significant prevalence of HTN in the adolescents/adults who does not pertain to ethnic groups, who show higher SBP levels in relationship with ethnic peers of EG-Map and EG-Aym.

Although lifestyle parameters such as PA, and nutrition play a key role in health, in Chile evidence is scarce from adolescents and adult ethnic groups such as those of Mapuche and Aymara ethnicity that represent an important amount population (12.8 %) (14). Due to from > 15 years old young adolescents have autonomy in their environmental behavior (i.e., they take their PA patterns, nutrition, and sleep hygiene independently of adults), to increase the information about lifestyle and cardiometabolic risk factors from these ages could increase the approach for future public politics in terms of early education and prevention of HTN and diabetes.

Following this, increasing the information regarding these minorities through representative studies could increase their knowledge to prevent HTN and diabetes in minorities that live in urban environments that usually left their cultural lifestyle patterns. For example, in the present study, the main findings indicated that DBP was significantly associated with PA of ‘moderate' intensity (Table III). In this sense, it is relevant to mention that Aymara ethnic groups are located in the north of Chile, which is characterized by higher temperatures, Mapuche groups are endemic in the central to southern portions of this country, characterized by a higher amount of rain and cold climate, and the non-ethnic population is located throughout the country's geography, where we presume that these climate factors are involved in the intensity of daily PA practice. On the other hand, in the PA of transport, usually termed also as ‘active commuting', the main part of PA of low to moderate intensity can be achieved by active commuting in more developed countries, where it is well known that using vehicles as a means of transport, is highly associated to sedentary lifestyles and cardiometabolic risk factors (26). Thus, it could be relevant to increase public politics for a major promotion of active commuting using bikes or walking in urban environments, where road security and street infrastructure could increase the health promotion in ethnic and non-ethnic adolescents and adults.

Due to there were differences in the frequency of nutrition among groups, particularly in dairy products, cereals, legumes, fruits, vegetables, and water consumption (Table II), we presume that independent of cultural or ethnic factors, there have been reported that the daily nutrition is also modified due to residence at rural/urban areas, the socio-economic income (27), and including the educational level (28). On the other hand, it is well known that both tobacco (29) and alcohol consumption promotes dangerous health risks whereas preventive public health mechanisms are strongly known (30). Additionally, other more recently known risk factors such as low sleep hygiene (e.g., 28.3 % of No-EG, reported to sleep < 7 hrs/day, where we presume that as this cardiometabolic risk indicator has been recently included in public health systems, there is low awareness in the adult population of this concern. For example, a low sleep time has been related to a wide variety of cardiometabolic alterations such as higher blood pressure or HTN (31), and higher fasting glucose levels of diabetes (32,33).

We observed that the No-EG group showed higher levels of SBP than ethnic groups EG-Map and EG-Aym. There are controversial findings in the literature, from the point of view that previous Latin-American studies have shown that ethnic minorities show elevated risk factors when these groups are living in urban contexts (15). Thus, we also presume that more than the ‘ethnicity' factor, the ‘urban living' could be a better factor explaining those markers of HTN and diabetes, due to the major possibilities of acquiring westernized habits (i.e., spending sedentary time in jobs, to be physically inactive, to consume more sugar, salt, and poor fruits, vegetates and water, together with poor sleep hygiene [34]) are more characteristic of the city context. Additionally, urbanization has been previously associated with lower possibilities of active commuting as we have mentioned, which is related to more diabetes prevalence for example (5,35). Due to these concerns, is that it has been proposed better neighbourhood regulations that favour more active living in communities, including more green areas, and better possibilities for active commuting (36). However, by contrast, other studies have reported that more than living in urban or rural areas, job occupation is a major factor associated with the prevalence of risk factors for HTN and diabetes in the adult population (37).

From a more general point of view, higher SBP levels in Chilean population are not new, because different isolated previous studies developed in ethnic young (9,38), adults (15,39), and non-ethnic populations have alerted this situation (1,2). For example, our research team has previously shown that schoolchildren of Mapuche ethnicity showed higher levels of SBP, and thus also a higher prevalence of HTN (38), being more recently these findings corroborated and complemented with sex differences in major risk of ethnic groups (40). The significance of our findings is that this is the first Chilean national study that includes lifestyle and cardiometabolic risk factors for HTN and diabetes including the two major ethnic groups, the Mapuche and Aymara populations, having our findings of characterization relevance for future more complex studies.

On the other hand, we observed that SBP, DBP, and GL were significantly associated with model 3 sleep hygiene. In this line, sleep is an important factor in blood pressure, neuroendocrine function, and glucose metabolism. Low sleep quality, for example, has been related to more metabolic and endocrine alterations, such as decreased insulin sensitivity, and increased appetite (41). Sleep restriction worse the hormonal system that regulates energy balance involving different hormones such as cortisol, insulin, ghrelin, leptin, and melatonin, that all are related to an increased risk of diabetes (42) and mortality (43). A low amount of sleep hours has been associated with all-cause mortality, obesity, and cardiovascular events ref. In addition, a reduced, sleep duration is a risk factor for both obesity and cardiovascular disease and represents a common complication that could contribute to worsening complications in metabolic and cardiovascular diseases (44).

Part of our secondary results included that alcohol consumption was also negatively associated with GL. In this regard, it is well known that a higher dose of alcohol consumption is related to more HTN, and moderate consumption per week is highly related to pancreatic cancer in subjects with prediabetes (45). However, there's also evidence that a light alcohol intake also reports minimal association with cardiometabolic risk, but when the analyses are adjusted by a beneficial lifestyle this minimal risk is attenuated, playing a critical role in the level of alcohol intake (46). Future studies should include the association between different amounts of sleep by adolescents/adults, including sleep quality with other cardiometabolic health markers.

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

The present study has the following limitations; i) the significant associations reported do not denote causality, ii) the PA levels (i.e., in terms of ‘intensity' were obtained from self-report by a standard the GPAQ v2 PA questionnaire, where it could be supra- or- underestimated, iii) despite the several ethnic groups information part of the NHS 2016-2017, we included only that related with Mapuche and Aymara ethnicity, but unfortunately, due to socio-politician concerns of some geographical regions, it could be possible that the instrument used here as the NHS 2016-2017 could not include all those ethnic populations considering that not all these groups are in the public health system, iv) we included a population > 15 years old including adolescents/adults with information of the NHS 2016-2017 that is recommended to interpret with rigor for future comparisons, v) around 80 % of the > 15-year-old participants in the NHS 2016-2017 were adolescents/adults living in urban areas, that may induce a predominant urban (i.e., westernized) lifestyle, and vi) the sample size among ethnics and non-ethnic groups were different. A strength of this study is that; i) the study contains representative data of the Chilean adult population (i.e., the NHS is applied in multi-stages, in person at home with families using a cross-sectional random, stratified by conglomerates), including lifestyle, and cardiometabolic risk factors outcomes of the two major ethnic groups of this country.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, there are differences in lifestyle between ethnic Mapuche, Aymara, and non-ethnic Chilean adolescents/adults (> 15 years of age), where PA of ‘moderate' intensity, and other modifiable lifestyle factors are also associated with blood pressure and fasting glycemia.

INSTITUTIONAL REVIEW BOARD STATEMENT

The Chilean National Health Surveys were funded by the Chilean Ministry of Health and led by the Department of Public Health of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. The Chilean National Health Surveys were approved by the Ethics Research Committee of the Faculty of Medicine at the same university.