Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

Anales de Psicología

versión On-line ISSN 1695-2294versión impresa ISSN 0212-9728

Anal. Psicol. vol.33 no.1 Murcia ene. 2017

https://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.33.1.229171

Women Occupying Management Positions in Top-Level Sport Organizations: A Self-Determination Perspective

Mujeres que ocupan cargos de gestión en organizaciones deportivas de primer nivel: una perspectiva desde la autodeterminación

Andrea Perez-Rivases, Miquel Torregrosa, Carme Viladrich and Susana Pallarès

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (Spain).

This work was supported by the Instituto de la Mujer (018/10) and the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (DEP2010/15561). We also wish to express our gratitude to Saül Alcaraz, Violeta Benischelli, Gerard Soriano and Yago Ramis for they valuable comments and support.

ABSTRACT

Framed in Self-determination theory (SDT), the purpose of this research was to examine whether the working environment of women in sport management positions could fulfil or thwart their basic psychological needs (BPN) and to explore the motivations that women managers experience in these positions. Eight female managers of top-level sport organizations participated in semi-structured interviews. Results showed that seven of them reported being in an environment that fulfilled their BPN and experienced autonomous motivation in their job. In contrast, one participant reported working in a context that thwarted her BPN and experienced controlled motivation. We present contextual antecedents that were considered satisfying or thwarting of the BPN of those women enrolled in management positions. Insomuch as BPN satisfaction is expected to be related to autonomous motivation and well-being, the current study provides a first insight regarding how sport organizations could promote women managers' BPN satisfaction and thus increase their autonomous motivation and well-being in such positions.

Key words: managers; motivation; basic psychological needs; gender; sport organizations; qualitative analysis.

RESUMEN

Bajo el marco teórico de la Teoría de la Autodeterminación (SDT), el propósito del presente estudio fue investigar si el entorno laboral de mujeres que ocupaban cargos directivos en el deporte era de satisfacción o frustración de las necesidades psicológicas básicas (BPN), y explorar sus motivaciones en estas posiciones. Se realizaron entrevistas semi-estructuradas a ocho directivas de organizaciones deportivas de primer nivel. Los resultados mostraron que siete de ellas reportaron estar en un entorno de satisfacción de las BPN y experimentaban motivación autónoma en su trabajo. Por el contrario, una participante reportó trabajar en un contexto de frustración de las BPN y experimentaba motivación controlada. Presentamos los antecedentes contextuales expuestos por las directivas que consideramos de satisfacción o frustración de sus BPN. Asumiendo que la satisfacción de las BPN está relacionada con la motivación autónoma y el bienestar, el presente trabajo proporciona una primera aproximación sobre cómo las organizaciones deportivas podrían promover la satisfacción de las BPN de las directivas y aumentar así su motivación autónoma y bienestar en el cargo.

Palabras clave: directivas; motivación; necesidades psicológicas básicas; género; organizaciones deportivas; análisis cualitativo.

Introduction

Sport environment has historically been a context dominated by men at all its levels (i.e., sportive, technique and managerial) and it is still predominantly masculine although it is becoming more equitable in some spheres (Fink, 2008). Inside sport agencies equity is further away, and many studies are rooted in this reality (see Burton, 2015, for a review). For example, Claringbould and Knoppers (2007) showed how men were able to control boards by negating affirmative action policies and to reproduce the male-dominated culture in those boards through the recruitment and selection processes. On the other hand, Spoor and Hoye (2014) found that top management support to gender equity practices was relevant to encourage women to pursue a leadership position in sport organizations. Although in the last years many initiatives have been implemented (e,g., European Parliament resolution about women and sport; European Parliament, 2003) and specific organisations have been created (e.g, International Working Group and the European Women and Sport Commission in 1993), women still play a little role inside sport agencies, specially as we ascend in the decision making process to top-level management positions. This fact is exemplified by the small representation of women in decisionmaking positions in major sport organizations, such as International Federations and National Olympic Committees (IOC, 2010) or the IOC itself, in which less than 22% of members are women (IOC, 2013). Thus, it seems relevant to study how an environment that has been traditionally masculine and it is still dominated by men, influences the motivation and well-being of those few women that are able to access to a top-level management position.

According to previous research, women have to face many barriers to attain a leadership position in sport organizations (e.g., Claringbould & Knoppers, 2007; 2012), and those women that have accessed to male-dominated occupations have to face other sort of barriers such as being marginalized in the decision-making processes (e.g., Chantelat, Bayle, & Ferrand, 2004; IOC, 2010; Sibson, 2010). Consequently, they tend to not stay in those positions for a while (Martin & Bernard, 2013), being also a problem for the sport organizations because as Wicker, Breuer, and Von Hanau (2012) empirically evidenced, women in management positions can be beneficial to that organizations. According to Martin and Bernard (2013), intrinsic motivation factors could be an element of women's resilience against hostile organizational practices. Thus, it is important to understand what lead these women to experience intrinsic motivation when they work in sport organizations.

Self-determination theory and basic psychological needs theory

In order to study motivation and well-being, tenets of self-determination theory (SDT; Deci & Ryan, 1985) have been widely applied to different environments, such as sport (see Ntoumanis, 2012) and work (e.g., Gagné & Deci, 2005). According to SDT, humans are active beings with an organ-ismic tendency to personal growth, integrity, and well-being when they interact with the environment, and this tendency is expected to be actualized so long as the required psychological nutriments are attainable (Deci & Ryan, 2000). These essential nutriments are the satisfaction of the basic psychological needs (BPN) for autonomy, competence and relatedness. The need for autonomy is the desire to feel as the origin of one's behaviour; the need for competence is the desire to interact effectively with the environment and to perceive opportunities to use one's abilities; and the need for relatedness, the desire to feel connected to others and to be respected by them (Deci & Ryan, 2000). Ryan and Deci (2000) highlighted the importance of the sociocultural context in the fulfilment or thwarting of BPN. Specifically, when an individual feels their three BPN satisfied in a given context (e.g., work, sport, academics), she/he will feel effective, will relate to others properly and will engage in activities that finds interesting (Deci & Ryan, 2000), and consequently, she/he will experience well-being (Ryan & Deci, 2000). However, BPN thwarting is associated with poor quality motivation, and low well-being (e.g., Deci & Ryan, 2000; Gillet, Fouquereau, Forest, Brunault & Colombat, 2012; Stebbings, Taylor, Spray, & Ntoumanis, 2012).

SDT establishes the existence of different motivations depending on the level of self-determination and explains how humans engage in their activities; that is, whether humans engage freely and volitionally in their behaviours (i.e., autonomous motivation defined by intrinsic motivation and self-determined regulations; that are the highest levels of self-determination) or behave under pressure or under feelings of obligation (i.e., controlled motivation; Gagné & Deci, 2005). Satisfaction or thwarting of the BPN influences the degree in which an activity is found to be important or interesting for itself (i.e., autonomous motivation) or not (i.e., controlled motivation).

Previous research in sport psychology has used SDT to study the motivation and or the well-being of athletes of different competitive levels and ages (e.g., Gagné, Ryan, & Bargmann, 2003; Mallett & Hanrahan, 2004; Moreno, Cervello & Gonzalez-Cutre, 2010; Ramis, Torregrosa, Viladrich, & Cruz, 2013), as well as sport coaches (e.g., Alcaraz, Torregrosa, & Viladrich, 2015; Allen & Shaw, 2009; McLean & Mallett, 2012). However, to the best of the authors' knowledge no studies in sport psychology have used SDT framework to explore the motivations experienced by those women managers working in sport organizations and to understand how contextual factors influence these motivations. In SDT contextual factors are defined as "recurrent variables that are systematically encountered in a specific life context but not in others" (Vallerand, 2007, p. 264) which in management of sport organizations are aspects like board directors meetings, users/athletes' relations. Both motivations and contextual factors can lead to negative or positive effects on turnover intentions (Richer, Blanchard & Vallerand, 2002). Thus, applied to sport management, women intentions to stay or not at the sport organization will affect gender equity in sport management positions (Spoor & Hoye, 2014), and also in the benefits of the sport organizations (Wicker et al., 2012).

Organizational psychology research conducted within the framework of SDT has aimed at understanding how motivation operates in work environments, highlighting in which conditions employees feel their BPN satisfied and what are the consequences. Gagné and Deci (2005) summarize the main elements of job motivation presented in previous SDT research. The authors highlighted that those working climates where supervisors engage in autonomy-supportive behaviours promote employees' BPN satisfaction. In turn, BPN satisfaction increases employees' autonomous motivation, which is an antecedent of positive work outcomes such as job satisfaction and psychological well-being.

Related to BPN, Boezeman and Ellemers (2009) found that volunteers and paid employees differed in the importance they gave to the fulfilment of each BPN; volunteers valued more relatedness satisfaction while paid employees valued more autonomy satisfaction, this point is relevant because most of sport managers in sport organizations are nonprofit employees. Allen and Shaw (2009) explored how two different types of sport organizations satisfied the BPN of women high performance coaches. The results showed that women enrolled in the organization where most of the coaches were women, felt higher quality of autonomy support (e.g., were able to work with their athletes independently from their organization), competence support (e.g., received more opportunities for developing and improving their coaching skills) and relatedness support (e.g., felt connected to other women coaches and club managers), than women enrolled in the organization where most of the coaches were men. Recently, Allen and Shaw (2013) used an interdisciplinary approach to examine the perceptions of women coaches regarding the working conditions of their sport organization, showing that some organizational structures and values (e.g., those that facilitated developing quality interpersonal relationships) were positively related to coaches' BPN satisfaction and enthusiasm for working in the organization. The studies that investigate the contextual factors in sport organizations that satisfy BPN of women coaches are scarce, and the studies with top-level women managers inexistent. Therefore, the main purpose of the present research was twofold: (a) to analyse the social antecedents that fulfil or thwart the BPN of women managers working in top-level sport organizations and (b) to explore their motivations and provide strategies to increase autonomous motivation and well-being.

Method

Design

The current study is a cross-sectional, qualitative and interpretative research. It is an adequate choice if we take into account that we aimed to describe an unexplored domain under SDT framework and with a very small population in size (i.e., women managers in top-level sport organizations)

Participants

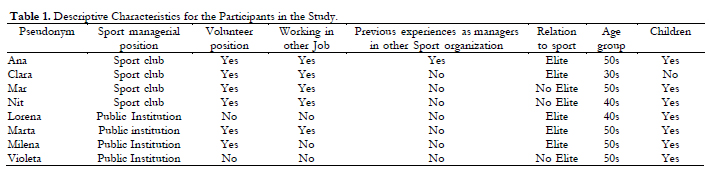

Based in a stratified purposeful sampling strategy, eight women managers working in top-level Spanish sport organizations participated in the study. We define top-level sport organizations and top-level management positions as the managerial board of sport organizations at national or international contexts (e.g., IOC, Manchester United). In order to preserve their anonymity, pseudonyms have been assigned and some descriptive details have been omitted.

All eight women were working in one of the sport management positions described in Table 1. Taking into account the volunteering characteristics of most of these positions, some managers had to conciliate this role with a different main paid job. Their academic level was at least a master degree and their sport experience differed depending on whether they were former elite athletes (five) or not (three). Elite sport criterion was reached if the participant had ever appeared in the lists of the Spanish Official Bulletin (BOE), where only those athletes achieving specific performance goals are included.

Interview guide

Data was obtained through semi-structured interviews based on an interview guide. Four main topics were included: (a) description of the sport management position or role participants were working in. We wanted to explore the level of autonomy and competence in the position by asking about the tasks developed, work organization and their contributions as managers (e.g., Which are your specific responsibilities and functions/tasks?); (b) the most relevant changes participants had experienced before arriving to their actual position. We wanted to explore the participants' previous experiences to the position in top-level sport organizations, previous works, studies, their relation to sport and so on (e.g., How was the process until you got into this position?); (c) situations and experiences lived during the beginning, development and ending of their transition to the current sport management position. We wanted to explore the relations with the other members of the managerial boards and the stakeholders of their organizations, the evaluation of their experiences in the position, and their motivations to be a manager (e.g., During the years you have been in this position, would you highlight some negative or positive situations you have lived?); and (d) how they had experienced being a woman that follows a managerial career linked to sport. We wanted to explore experiences and perceptions related to gender and the fact of being a woman in a male environment (e.g., Just for the fact of being a woman, which barriers or advantages did you have or did not have?). However, the interviews were flexible, allowing the participants to describe relevant situations not initially included in the interview guide. In addition, probes and follow-up questions (e.g., could you explain it in more detail, please) were used to go in depth into the interviewee's responses (Patton, 2002).

Procedure

This study followed the ethical guidelines established by the ethics committee of the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona. First, we contacted with different top-level sport organizations, which offered us 14 possible participants for the study (i.e., women occupying a management role in sport organizations) but we only could establish contact with eight of them. The eight participants were informed about the purpose and the procedure of the study and once they agreed to participate, they signed an informed consent. Interviews were conducted by the second and the fourth authors, were recorded and transcribed verbatim. They lasted between 40 and 80 minutes, totalling 430 minutes recorded.

Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using thematic analysis with a deductive approach to the content (Braun & Clarke, 2006) and following the six steps suggested by these authors (see Table 2).

This analysis organizes and describes data in rich detail (Sparkes & Smith, 2014). Software Atlas.ti 5.0 was used as an assistant to organize data codification and interview analyses. Fernández-Alcántara, García-Caro, Pérez-Marfil and CruzQuintana (2013) described how the program works, and Zamora et al., (2012) explained its main functions.

In order to guarantee the rigour of the study (Maxwell, 2002), interviews were audio-recorded, transcript verbatim and proofread by the first author. Interrater reliability was estimated following the three-stage process explained in Campbell, Quincy, Osserman and Pedersen (2013). Cohen's kappa was calculated for the independent scores of two coders. Cohen's kappa was 0.83, and was interpreted using the cut-off scores of Landis and Koch (1997) who considered that 0.81-1 scores were good to perfect agreement. Three researchers, external to the study audited the category system considering the data representation and the theoretical depiction. Their intervention help authors to refine the names of the themes and subthemes. Finally, results were provided to women managers in order to check how accurately their' realities were represented in the study. They agreed with the results.

We also controlled the genesis of data, differentiating information obtained directly by the participants' experiences and information obtained by the researchers' interpretations of these experiences in relation with the SDT framework. Both, during the analysis and in the results section.

Results

Data were clustered into three main themes: (a) antecedents of managers' BPN satisfaction (i.e., autonomy, competence and relatedness), including six subthemes; (b) antecedents of managers' BPN thwarting (autonomy, competence and relatedness thwarting), including four subthemes; and (c) managers' motivation when antecedents satisfy or thwart their BPN, with four subthemes (see Figure 1 for a summary). The specific antecedents (i.e., subthemes) were described by the participants. However links between antecedents and BPN satisfaction or thwarting (i.e., main themes) were obtained as a result of researchers' interpretation of the data, which was based on SDT tenets and definitions.

Theme 1: Antecedents of Managers' BPN Satisfaction

These antecedents refer to the climate created in the sport environment where participants worked, and include the factors influencing women managers' BPN satisfaction. Analysis showed that seven out of eight participants reported working on an environment that promoted BPN satisfaction. A total of six subthemes were identified as antecedents of manager's BPN satisfaction: Three of them belonged to autonomy, one to competence and two to relatedness and they are presented in the next sections.

Autonomy satisfaction

Autonomy satisfaction is related to situations where managers feel they can give their opinions freely, where they perceive possibilities to choose and where they feel as the drivers of their own acts. Three different subthemes were identified: (a) democratic boards, (b) freedom of choice in their position and (c) personal needs recognition.

Democratic boards. Women managers reported characteristics of autonomy support in their sport organizations when organization councils were democratic and respected the opinion of all their members. Most of the decisions were made in council meetings, women managers valued not being coerced or forced to accept imposed decisions, and valued working in an environment where everybody felt free to express their own opinions, even when their ideas were not shared by most of the council. Mar said "if I don't agree I always say my thing, people respect you a lot for this...". When asked about how free they felt when participating in decision-making processes, one of the managers (Nit), explained:

"I've never perceived (...) any imposition about any decision that has been a problem for me, you know? It has been some debate (...) you can present your ideas, the ideas are listened, and in the end they are voted or they are not voted".

For these managers, perceiving that their opinions were respected was more important than the fact of their proposals being accepted or not. Additionally, participants valued feeling that they could propose projects, initiatives or action plans in their councils. Thus, in those democratic boards, women managers felt that their opinions were listened, respected and valued, all of them words associated with the fulfilment of their need for autonomy.

Freedom of choice in their position. This subtheme refers to the possibility of making their own choices regarding their working tasks and functions. Sometimes, managers could choose whether they were interested in doing a particular task or function. In other cases, their supervisors or workmates asked them directly if they wanted to lead a certain project or function. As Mar stated "sometimes is the other way around, and they [the board of directors] are the ones that have ideas. They tell us, and if those ideas look good to us, we carry them out". The best example of this freedom of choice could be found in Ana's experience. She explained that when she initially refused a job in a sports federation because she did not like the functions proposed, the federation made her a new offer with entirely new functions to carry out.

Personal needs recognition. Participants felt that their individual needs were recognized when they felt able to organize their time and plan their agendas, in order to balance their job with other spheres of their lives (e.g., maternal role). Lorena explained "now I benefit from a reduction in my working-hours to combine [work] with family life and I work five hours day (...) the agreement allows me to balance everything without losing projection". This point is important because when participants were asked about the causes why there were only few women pertaining to boards of directors, one of the reasons participants highlighted was the decision to have children. In many cases, this reason forced women to choose between being a mother or a manager. As Marta noted:

"Those women that make it [succeed in top-level sport management positions] have done a great effort and are people that have really clear job goals, and most of the times they do not consider or stop considering other life options".

However, if their job gives them some advantages, they can be both mothers and managers if they want to. As explained by our participants, these advantages include tasks that could be done at home using technological support (i.e., e-mails, telephone calls) as well as flexible schedules that allow them to not be forced to choose between different life spheres.

Competence satisfaction

Regarding how the social context could satisfy participants' need for competence, the results presented in this section include a subtheme (i.e., environment that trust them) related to the conditions that allow women managers to effectively develop their role abilities and to feel competent in their tasks and functions.

Environment that trust them. Participants perceived that a work environment trusted them when their supervisors and significant others had confidence in their abilities and in what they could bring to the organization, and also when they received help and recognition (e.g., positive feedback) from mates, supervisors and users. In these environments, supervisors usually took them into account to lead certain projects and recognized their work and effort, as Lorena explained: "A key person is the former director, he trusted me (...). He is the reason why I'm currently working here". Thus, managers worked in environments where they could develop their capability and prove their skills, which probably could not have been possible in a social environment that had not relied on them.

Perceiving that people trusted them was relevant, but receiving support also helped managers to improve their capabilities. One manager, Clara, explained that she received help from two male presidents "My favourite presidents are from [Club names] they helped me a lot, they gave me their opinion and they shared their expertise with me". When this type of support was available, our participants really valued it. However, in our study this environmental support was more remarkable for its absence than for its presence, and consequently it will be further discussed below in the section presenting the antecedents of BPN thwarting.

Relatedness satisfaction

The results of this section present two subthemes related to the conditions that allow women managers to feel appreciated, well related to others, and valued as human beings. The antecedents that fulfil managers' need for relatedness include: (a) caring environments, and (b) institutional support.

Caring environments. Managers perceived to be working in caring environments when their job relationships were so good that they viewed their mates as members of a second family, "for me, that sense of belonging to this group has been more than just belonging to a typical board. I feel it more like an extension of my family life" (Nit). This feeling arises from sharing the same goals (e.g., development of the sport organization), having personal affinity, and doing activities together outside of work. A caring environment could also be favoured by those club users or athletes that managers work with. "...I think that [athletes] like me so much, they're showing me love constantly" (Milena). Managers used words such as "friendship", "second family", "affection" and "affinity" to define these caring environments. Moreover, it is important to note that these caring environments are characterized by the acceptance of women. When questioned whether they were well received in their own boards or in boards they collaborate with, two participants explained that they felt totally accepted everywhere they went. However, they also expressed that they were involved in a male environment that at some point was even sexist. In Mar words "if she's not going [her only female colleague], maybe there are eight or ten men and I'm alone, but they treat me nicely". The other women managers explained that sometimes they had relatedness problems with some of their male colleagues, but they also expressed that, in general, relationships with their mates were good and caring, particularly with presidents and direct supervisors, which sometimes made an effort to include women in those male environments, as Milena explained: "He [the president] probably also thought that this move was necessary, that "it [the position] had to be occupied by a woman".

Institutional support. This support came from the personal relationships that participants had with the directors and managers of the institutions that uphold them. Experiencing that the institution supports them proves that they were well connected and, in some way, cared "when we were hanging by the last thread, searching for possible complicities, that we found for example on the town hall. It was difficult to survive but the truth is that I felt accompanied" (Marta). Another manager expressed in the same way: "The Administration, no matter the colour or the flag, always received us and they actually gave us some help" (Violeta).

Finally, certain institutions created a favourable atmosphere for managers to feel connected with their families, as some of their functions and liabilities allowed the participation of their relatives, and managers were able to share activities and hobbies with their family. Two managers referred to that "the [club name] is a social club, and in all the institutional events where we can go, we all go [the family]" (Nit). In such situations, managers felt lucky because they could spend more time with their families.

Theme 2: Antecedents of Managers' BPN Thwarting

These antecedents refer to the climate created in the sport environment that thwarted women managers' BPN. Experiences and opinions regarding those antecedents were mainly expressed by: (a) one manager, who found herself in a hostile work environment, (b) the experiences of another manager in the two boards of directors where she used to work, (c) the knowledge and opinions of our participants concerning situations that other women managers had lived. Four subthemes were identified as antecedents of managers' BPN thwarting.

Autonomy thwarting

Autonomy thwarting was related to situations where managers did not feel able to give their opinions freely and felt limitations to be the drivers of their own acts. One antecedent of managers' autonomy thwarting was found: (a) coercive boards.

Coercive boards. These boards were defined as work teams where group dynamics were characterized by the coercion that one or more board members exerted on the other members. One of the managers (Ana) explained that in one of her former sport management roles, the board pressured her to vote for a project that she thought that was not the best option at all; as she decided to stand firm on this, she was told "Then you're the opposition". This situation made her perceive that she had no freedom for choosing or voting differently, "you are coercing the people here and I don't like that. Can we vote freely?" In addition, she did not receive any reasonable explanation regarding why she was supposed to vote in a way or another. Those situations of coercion were perceived by the managers as sources of ill-being causing that they thought about leaving their job or even finally step down from the management position. Ana decided to quit from her former responsibility position due to her sense of impotence and ill-being. She did not feel free to decide, and perceived that male members ignored her comments and opinions. This situation was experienced as really damaging and she preferred stepping down from her position than continuing in that harmful environment, although she wanted to work there.

The participants in our study that had experienced those situations explained that being a woman made it so much worse. Clara expressed:

"... they [men managers] are interested in a profile of young woman with studies but who doesn't bother a lot (...) I asked a question in a question-and-answer session and I had the feeling that it bothered them (...) like 'look, the girl is a pain in the ass'".

Competence thwarting

The antecedents that thwarted participants' need for competence were described as (a) rigid environments, and (b) gender limitations in their job development.

Rigid environments. In some cases, boards or users were really used to a particular functioning and were not open to changes, initiatives or proposals suggested by women managers. Our participants firmly believed that these changes were an improvement for their organizations. The participants also stated that in the cases where they were finally able to develop those initiatives they had to fight a lot "sometimes to contribute things here I had to take the knife out and put it between my teeth!" (Milena). This situation of fight was experienced as a hard and very exhausting challenge, where managers' need for competence was actively thwarted. Managers knew that they could contribute to the organization with their expertise, but the environment restricted their abilities.

Gender limitations in their job development. This subtheme presents attitudes and thoughts that some male directors or other people (e.g., mates, users, athletes) have towards women managers that generate subtle discriminating situations. Those limitations include situations where women are prevented from arriving to top-level sport management positions or from being involved in certain projects, although they have the same abilities than men: "they don't choose a woman before a man, even with the same knowledge or greater" (Ana). Participants also reported differences in their perception of help and support received as a man or a woman manager. An example of these differences is the lack of help received regarding the acquisition of abilities to decide or discuss certain projects or issues. In Marta's words: "[men] are mentored in a very subtle way (...) however, this process of mentoring isn't applied by men mentors to women in the clubs". The lack of support and counselling perceived by the managers could have thwarted their need for competence, as they really did not know how to behave in certain situations.

Relatedness thwarting

The antecedents thwarting participants' need for relatedness were reduced to one subtheme: Disrespect.

Disrespect. This subtheme includes those social agents (e.g., male directors) that do not support nor respect women participation in managerial environments, particularly when women show initiative and propose changes; that is, when women managers are combative and do not agree with merely seeing, hearing and keeping quiet. Participants expressed that they suffered this type of discrimination in the boards where they were working or in their relationships with other clubs or institutions. "I've had to endure very sexist conversations (...) there are still some profiles, especially well-established intransigent male directors, that are first shocked because there is a woman [in the board], then because I'm young, and then because I don't agree with them." (Clara). There are situations where women managers did not know whether the disrespect received was due to gender issues or lack of personal affinity. Milena explained "concerning gender issues, sometimes it's really difficult the border that limits the doubt regarding whether it's a gender issue or that they dislike that particular woman. Or because it's not the type of woman they want in such position". Thus, it seems extremely difficult to determine whether the negative relationships that some male managers establish with our participants are due to gender issues or not. Our participants also related that some male managers use particular strategies, such as hiring a certain profile of women (e.g., less combative) in order to prove that they do not have problems regarding the gender of their subordinates. Three participants pointed out that there was an increasing tendency of men hiring female managers, but they were not sure whether this increase was owing to cleaning supervisors' image, obtaining grants or because men found it truly important.

Theme 3: Female Managers' Motivations

This section shows the connections between the previously presented antecedents and managers' motivation, including the forms that this motivation could adopt. These motivational forms are clustered in four subthemes, three related to autonomous motivation and one referred to controlled motivation.

Autonomous motivation

Autonomous motivation is assumed when participants engage volitionally in their behaviours as sport managers. Seven out of the eight participants referred autonomous motivation to work in their management position. Those seven managers had in common that they were working in environments that in general fulfilled their BPN (i.e., these environments positively contributed to their feelings of autonomy, competence and specially relatedness). The motivations of those female managers could be grouped in three subthemes: (a) passion for their job (b) achieving or improving something important, and (c) connection to sport.

Passion for theirjob. Six out of the eight participants reported that they carried out their managerial functions and tasks because they loved doing it. Our participants repeatedly used words such as "love", "like", "devotion", "attract", "enjoy", "passion", "dream" and "happiness" to describe their feelings as top-level sport managers. As clearly stated by one of the participants (Mar): "Nowadays, it [club name] is the motor of my life. I mean, it's my family and the club". It has to be noted that those participants whose work motivations were related to the inherent pleasure experienced in their management position, were also the ones that described that their work environment with attributes related to BPN satisfaction.

Achieving or improving something important. This kind of motivation appears when managers want to carry out their managerial functions in order to implement or to achieve something perceived as important and congruent with their values. Most of the times their actions headed towards helping other people improve their situation, or increasing the promotion of a certain sport. For example, for one of the managers her motivation was to improve women's sport. "Competition meetings were all about boys, boys, boys. When there were five minutes left, it was like 'well, what do we do with the girls this weekend?' And so it was the way to gain ground" (Ana). Similarly, managers also expressed their beliefs about the feasibility and importance of their project as forms of autonomous motivations. Violeta said: "to me, it looks wonderful, a fantastic project". As she related in her interview, Violeta had always firmly believed in the third sector; at the time of the interview she was a manager in a sport foundation and considered that her work was really important. In those cases, motivation is more related to integration between managers' values and their way of thinking than to the experience of inherent enjoyment and pleasure in their job.

Connection to sport. Another relevant type of autonomous motivation referred to the managers' opportunity to continue connected to sport and athletes. This type of motivation was mostly expressed by those participants that were former elite athletes, but it was also present in some of the participants that were not. Lorena defined it as: "Being able to live through the athletes sensations that I have had", or in Violeta's words "using sport as an integration tool, (...) looked wonderful to me, I've always believed in this facet of sport". Both are examples of autonomous motivations related to their management position. When regulated by their connection to sport, managers' view sport as the central axis of their motivation and experienced feelings of love for sport, its values, and everything that sport entails.

Controlled Motivation

Controlled motivation is referred when managers engage in an activity under pressure or under feelings of obligation. Only Clara showed signs of controlled motivation. It was also the only participant that was involved in an environment that thwarted her BPN, particularly her needs for competence and relatedness.

Taking responsibility. The type of controlled motivation that appeared along the interview referred to the sense of responsibility. When Clara expressed their reasons to remain in her management position, their motives were related to her sense of duty and responsibility, both linked to her commitment with the sport organization. She stated "you are carrying out a project with little feasibility and in the end you just do it (...) because you found yourself in a situation where after all you take the responsibility and you can't leave it until you finish". However, it has to be noted that all the participants were regulated by different motivations and none of them experienced motivations that were solely external (i.e., carry out their functions to obtain something in return, money or other benefit like public visibility). One of our managers explained that there were some male managers whose motivation was to take profit from their position in some sense "[some male managers] accepted a position at the football or the canoeing federation to see if they can sell more sofas or pans" (Milena). None of the participants expressed that this motivation was important for women, neither as their own motivation nor as the motivation of the other women they referred to during the interviews.

Discussion

The main purpose of this study was to analyse the social antecedents that fulfil or thwart the BPN of women managers working in top-level sport organizations and to examine how BPN satisfaction and thwarting were related to their job motivation. The results show that most of the participants reported to be working in environments that fostered BPN satisfaction; environments where they were able to choose and to give their opinion, where they could prove their competence and efficacy, and where the relationships among workmates, users and supervisors were positive. Only one of the managers perceived to be involved in an environment that thwarted her BPN, specially her needs for competence and relatedness. In addition, those women managers that reported to be working in an atmosphere that fulfilled their BPN also expressed a sense of autonomous motivation for their job. In contrast, the manager that perceived to be an environment that thwarted her BPN, reported to be regulated by controlled motivation. The findings from the current study are in line with Gagné and Deci's model (2005) due to the fact that autonomy-supportive environments foster managers' job autonomous motivation.

The findings of the current study underline that job environments fostering autonomy satisfaction were highly valued by our participants, especially when managers could choice democratically in their councils, and when everybody felt free to give their opinion and was listened. In contrast, coercive boards were environments that thwarted managers' BPN. In those controlling environments thinking different led to conflicts and not all the board members were included in the decision-making processes. Our results regarding the coercive boards seem to complement the results of Sibson' (2010) case study. Sibson showed that in a sport organization where the same number of men and women were included in the board of directors, there were certain situations that probably limited women's autonomy, due to some forms of exclusionary power (i.e., not having the opportunity to decide which activities to do, how to assign new employments or how to invest resources). Furthermore, these situations could push women to leave their position as it occurred in our study with one of the managers. She experienced a lack of autonomy because she was not allowed to decide freely, and male members ignored her comments and opinions. This situation was experienced as really damaging, showing that BPN thwarting is associated with less well-being (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Gillet et al., 2012).

In addition, having the opportunity to choose which tasks to do, deciding how to perform them, and deciding some issues inside boards was highly valued by these managers. However, for them it was also necessary to be recognized as human beings, taking into account their personal needs, not related to their positions. For that reason, managers' need for autonomy was supported when their job environment take into consideration their individual needs, allowing them to manage their own time in order to be able to balance the different spheres of their life. These results are in line with Allen and Shaw's study (2009) with women high performance coaches. In their study, coaches felt their autonomy was fostered when the sport organization considered and supported some special situations regarding their private life, easing conciliation between job and personal spheres. This flexibility is very important for women in leadership positions (Bruening & Dixon, 2007), which are frequently unpaid (Cameron, 1996), because their environment (e.g., family duties, social stereotypes) or her own attitudes could force them to choose between those spheres, especially when they are mothers (e.g., Dixon & Bruening, 2007). In our study, this topic is particularly relevant because seven out of eight participants were mothers.

Related to the antecedents that could foster managers' need for competence, in the current study we found that participants valued working in an environment that trusts them. Such an environment helps to increase managers' competence satisfaction as they perceived that their mates and supervisors rely on their competences/abilities to lead projects and not only to fulfil a quota in the board. In a similar way, Chantelat et al., (2004) stated that women wanted to be valued by their abilities and competences and not to fulfil the gender needed in a quota. In the same study it was found that the quota system was a little contradictory: including women at boards in order to fulfil a quota instead of hiring them due to competence criteria could be counterproductive for the woman herself or could be an opportunity to access to a managerial position. This idea was also a concern shared by our participants. It seems that in some cases, gender quota systems and political measures are the only way for women to participate in the boards of directors of sport organizations, however, many authors conclude that these conditions do not seem to be sufficient (Adriaanse & Schofield, 2014; Sibson, 2010; Spoor & Hoye, 2014) and this is also found in our results. Women occupying top-level sport management positions need to feel useful in their roles, which require that managers need to be allowed to lead projects in order to show they are able to do it, to get positive feedback when they achieve a goal valued for the organization, and to receive advice regarding their functions, at least in the beginning. Regarding the latter, we found that our participants valued receiving help and support, but sometimes they did not obtain them. Previous research has highlighted the relevance that having mentors has for women in order to gain confidence and experience both in their role as sport managers (e.g., IOC, 2010; Weaver & Chel-ladurai, 1999) or coaches (e.g., Allen & Shaw, 2009; Kilty, 2006). In this line, the current study reinforces the conclusions regarding mentoring stated in past research.

According to the results, our participants, six of whom were volunteers, valued being in a job environment that fostered the satisfaction of their need for relatedness. Specifically, women managers highlighted the relationships established with members of their boards, athletes or club users, and the satisfaction experienced when these relationships were positive (i.e., caring environments). In contrast, they reported suffering from ill-being when their need for relatedness was thwarted. Our results support the findings of Boezeman and Ellemers' study (2009), which compared the importance that volunteers and paid employees associated to each BPN. Boezeman and Ellemers found that the need for relatedness was the most valued by volunteers and it was also their main predictor of job satisfaction and intention to remain in the organization. In this line, our participants explained that those situations where they felt integrated, valued and well-related fostered their need for relatedness, and were clearly related to their well-being. Although Deci and Ryan's study (2000) highlighted that the needs for autonomy and competence are essential to experience autonomous motivation and well-being, recent studies have shown the relevant role of the BPN for relatedness (Alcaraz et al., 2015; McLean & Mallett, 2012). In a study conducted with development coaches, Alcaraz et al., (2015) found that among the three needs, relatedness was the one that mostly predicted coaches' self-determined motivation and psychological well-being. In a similar way, McLean & Mallett (2012) found in their qualitative study that BPN for relatedness was also very important for coaches of different competitive levels (i.e., participation, development and highperformance).

Regarding the reasons why participants engaged in sport management roles, three subthemes were related to autonomous motivation (i.e., passion for their job, achieving or improving something important, and connection to sport). In contrast, only "taking responsibility" emerged as a type of controlled regulation. Some of our results are in line with those presented in McLean and Mallett's (2012) study: connection to their sport, passion for the job and non-relevance of financial rewards. Concerning the connection to sport, participants in both studies (i.e., male and female coaches in McLean and Mallett's study, only women managers in our study) related the feeling experienced while being involved in sport and particularly while dealing with athletes. In regard to their passion for the job, women managers and coaches used similar words to describe their motivation to perform the tasks of their job, such as "enjoyment", "love" and "passion". It also has to be noted that none of the participants in both studies reported financial or other external reasons for occupying their job position. The similarities between our results and those from previous coaching research reinforce the idea that SDT is a broad framework that is not only relevant to study athletes' and coaches' motivation and well-being, but also women sport managers'. Thus, our study responds to the necessity highlighted by Ntoumanis (2012) to extend SDT' research towards unexplored populations. Recently, Martin and Bernard (2013) stated that intrinsic motivation (i.e., form of autonomous motivation) is an element of women's resilience in hostile male-dominated contexts. In line with these authors, we would expect that the manager that was working in a context of BPN thwarting and showed controlled motivation will no longer continue in their management position. Regarding the results of the current study and SDT literature, our concern, is that it seems more unlikely to be autonomously motivated in contexts that are not autonomy-supportive. That is why initiatives focused on promoting that sport organizations support the BPN satisfaction of their women managers are necessary to increase and maintain the ratio of women participation in these organizations, and this study could provide some useful knowledge based on real experiences of top-level women managers to promote this kind of initiatives.

In terms of the methodological implications of the study, qualitative methodology allowed a deeper examination of the specificities experienced by women managers in the top-level management contexts. Moreover, only qualitative methodology allowed participants to contribute with relevant information not considered by researchers beforehand, as this population remained unexplored under SDT framework at the time of data collection, so it was an adequate way to approach our objective. Although the sample size could be seen as a limitation, there is a very low percentage of women (22%) occupying management positions in Spain (Yusta, 2015). Tacking into account that participants of the current study occupied management positions in top-level sport organizations, the ratio of possible participants was even scarcer.

Along with the contributions of the current study, it is also necessary to mention some limitations. First, some women managers reported past situations occurred in boards they used to work on, these retrospective reports enabled us to obtain rich knowledge based on their experiences that although they are really interesting for our study could have had some degree of memory bias. The second limitation is related to the notion that sport organizations are multilevel entities (Dixon & Cunningham, 2006) where it is important to study the factors that have an influence on all their levels (i.e., individual, organizational and structural). Nevertheless, our analysis was mostly focused on the individual level (motivation and BPN of women sport managers) and organizational level (working conditions in sport organizations). We suggest this particular limitation could be further explored in future research. The third limitation is related to the paid/volunteer position of the female managers on the board, however we did not find any relevant difference regarding this issue.

Conclusions

In the current study, we tried to understand the characteristics of the environment where women sport managers work by analysing the situations that potentially fulfil or thwart their BPN and exploring how this environment influences their job motivation under the SDT framework. To do this, we have used a qualitative approach methodology which is actually uncommon in this research' area, and we have also extended the investigation focus beyond the athlete population, as had been requested in Ntoumanis (2012). Taking into account that BPN satisfaction is related to autonomous motivation and well-being (Deci & Ryan, 2000), our study has found social antecedents in sport organizations that foster women managers' BPN satisfaction, not thwarting.

Thus, results provide some practical implications for those top-level sport organizations interested in increasing their women managers' autonomous motivation and well-being. Those organizations should promote: democratic boards respecting all different opinions, trust the managers in leading important responsibilities, and emphasizing positive social interactions with board members and stakeholders. At the same time, these organizations should avoid: coercive boards where different opinions are hindered, gender limitations in their job development, and disrespect with intentional or "innocent" sexism jokes. Such an initiative would allow having a higher number of women managers working in top-level sport organizations adding effectiveness to the gender quota system used in the last decades.

Author note.- Andrea Perez-Rivases, Departament de Psicologia Social, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona; Miquel Torregrosa, Departament de Psicologia Bàsica, Evolutiva i de l'Educació, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona; Carme Viladrich, Departament de Psicobiologia i Metodologia de Ciències de la Salut, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, and Susana Pallarès, Departament de Psicologia Social, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

References

1. Adriaanse, J., & Schofield, T. (2014). The impact of gender quotas on gender equality in sport governance. Journal of Sport Management, 28(5), 485-497. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2013-0108. [ Links ]

2. Alcaraz, S., Torregrosa, M., & Viladrich, C. (2015). How coaches' motivations mediate between basic psychological needs and well-being/ ill-being? Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 86(3), 292-302. doi: 10.1080/02701367.2015.1049691. [ Links ]

3. Allen, J. B., & Shaw, S. (2009). Women coaches' perceptions of their sport organizations' social environment: Supporting coaches' psychological needs?. The Sport Psychologist, 23, 346-366. [ Links ]

4. Allen, J. B., & Shaw, S. (2013). An interdisciplinary approach to examining the working conditions of women coaches. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 8(1), 1-18. [ Links ]

5. Boezeman, E. J., & Ellemers N. (2009). Intrinsic need satisfaction and the job attitudes of volunteers versus employees working in a charitable volunteer organization. Journal of Occupational and Organisational Psychology, 82, 897-914, doi: 10.1348/096317908x383742. [ Links ]

6. Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [ Links ]

7. Bruening, J. E., & Dixon, M. A. (2007). Work-family conflict in coaching II: Managing role conflict. Journal of Sport Management, 21, 471-496. [ Links ]

8. Burton, L.J. (2015). Underrepresentation of women in sport leadership: A review of research. Sport Management Review, 18(2), 155-165. doi: 10.1016/j.smr.2014.02.004. [ Links ]

9. Cameron, J. (1996). Trail blazers: Women who manage New Zealand sport. Christchurch, New Zealand: Sports Inclined. [ Links ]

10. Campbell, J.L., Quincy, C., Osserman, J., & Pedersen, O.K. (2013). Sociological Methods & Research, 42(3), 294-320. doi: 10.1177/0049124113500475. [ Links ]

11. Chantelat, P., Bayle, E., & Ferrand, C. (2004). Les représentations de l'activité des femmes dirigeantes dans les fédérations sportives françaises: Effets de contexte et ambivalences. Staps, 66(4), 143-159. doi: 10.3917/sta.066.0143. [ Links ]

12. Claringbould, I., & Knoppers, A. (2007). Finding a 'normal' woman: Selection processes for board membership. Sex Roles, 56(7-8), 495-507. doi: 10.1007/s11199-007-9188-2. [ Links ]

13. Claringbould, I., & Knoppers, A. (2012). Paradoxical practices of gender in sport-related organizations. Journal of Sport Management, 26(5), 404-416. [ Links ]

14. Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Nueva York: Plenum Press. [ Links ]

15. Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The "what" and the "why" of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227-268. [ Links ]

16. Dixon, M. A., & Bruening, J. E. (2007). Work-family conflict in coaching I: A top-down perspective. Journal of Sport Management, 21, 377-406. [ Links ]

17. Dixon, M. A., & Cunningham, G. B. (2006). Multi-level analysis in sport management: Conceptual issues and review of aggregation techniques. Measurement in Physical Education and Exercise Science, 10(2), 85-107. [ Links ]

18. European Parliament (2003). Women and Sport: European Parliament resolution on women and sport (2002/2280(INI)). Retrieved from http://www.europarl.europa.eu/sides/getDoc.do?pubRef=-//EP//NONSGML+TA+P5- TA-2003-0269+0+DOC+PDF+V0//EN. [ Links ]

19. Fernández-Alcántara, M., García-Caro, M.P., Pérez-Marfil, N., & Cruz-Quintana, F. (2013). Experiencias y obstáculos de los psicólogos en el acompañamiento de los procesos de fin de vida. Anales de Psicología, 29, 1-8. [ Links ]

20. Fink, J. S. (2008). Gender and sex diversity in sport organizations: Concluding comments. Sex Roles, 58(1-2), 146-147. doi: 10.1007/s11199-007-9364-4. [ Links ]

21. Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Behavior, 26, 331-362. [ Links ]

22. Gagné, M., Ryan, R. M., & Bargmann, K. (2003). Autonomy support and need satisfaction in the motivation and well-being of gymnasts. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 15, 372-390. [ Links ]

23. Gillet, N., Fouquereau, E., Forest, J., Brunault, P., & Colombat, P. (2012). The impact of organizational factors on psychological needs and their relations with well-being. Journal of Business Psychology, 27, 437-450. [ Links ]

24. IOC (2010). Gender equality and leadership in Olympic bodies: Women, leadership and the Olympic movement 2010. Retrieved from: http://www.olympic.org/Documents/Olympism_in_action/Women _and_sport/GENDER_EQUALITY_AND_LEADERSHIP_IN_OLYMPIC_BODIES.pdf. [ Links ]

25. IOC (2013). Factsheet women in the Olympic movement. http://www.olympic.org/Documents/Reference_documents_Factsheets/Women_in_Olympic_Mov ement.pdf. [ Links ]

26. Kilty, K. (2006). Women in coaching. The Sport Psychologist, 20(2), 222-234. [ Links ]

27. Landis, J.R., & Koch, G.G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement of categorical data. Biometrics, 33, 159-174. doi: 10.2307/2529310. [ Links ]

28. Mallett, C. J., & Hanrahan, S. J. (2004). Elite athletes: Why does the "fire" burn so brightly? Psychology of Sport and Exercise 5, 183-200. doi: 10.1016/S14690292(02)00043-2. [ Links ]

29. Martin, P., & Bernard, A. (2013). The experience of women in maledominated occupations: A constructivist grounded theory inquiry. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 39(2), 1-12. doi: 10.4102/sajip.v39i2.1099. [ Links ]

30. Maxwell, J. A. (2002). Understanding and validity in qualitative research. In A.M Huberman & M.B. Miles (Eds.), The qualitative researched s companion (pp. 37-63). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [ Links ]

31. Moreno, J.A., Cervelló, E., & González-Cutre, D. (2010). The achievement goal and self-determination theories as predictors of dispositional flow in young athletes. Anales de Psicología, 26(2), 390-399. [ Links ]

32. McLean, K. N., & Mallett, C. J. (2012). What motivates de motivators? An examination of sports coaches. Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy, 17, 21-35. [ Links ]

33. Ntoumanis, N. (2012). A self-determination theory perspective on motivation in sport and physical education: Current trends and possible future research directions. In G.C. Roberts and D.C. Treasure (Eds.). Motivation in Sport and Exercise: Volume 3. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, pp. 91-128. [ Links ]

34. Patton, M.Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. [ Links ]

35. Ramis, Y., Torregrosa, M., Viladrich, C., & Cruz, J. (2013). El apoyo a la autonomía generado por entrenadores, compañeros y padres y su efecto sobre la motivación autodeterminada de deportistas de iniciación. Anales de Psicología, 29, 243-248. [ Links ]

36. Richer, S.F., Blanchard, C., & Vallerand, R.J. (2002). A motivational model of work turnover. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32, 2089-2113. [ Links ]

37. Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55, 68-78. [ Links ]

38. Sibson, R. (2010). I was banging my head against a brick wall: Exclusionary power and the gendering of sport organizations. Journal of Sport Management, 24(4), 379-399. [ Links ]

39. Sparkes, A. C., & Smith, B. (2014). Qualitative research methods in sport, exercise and health. From process to product. Abingdon: Routledge. [ Links ]

40. Spoor, J. R., & Hoye, R. (2014). Perceived support and women's intentions to stay at a sport organization. British Journal of Management, 25(3), 407-424. doi: 10.1111/1467-8551.12018. [ Links ]

41. Stebbings, J., Taylor, I. M., Spray, C. M., & Ntoumanis, N. (2012). Antecedents of perceived coach interpersonal behaviors: The coaching environment and coach psychological well- and ill-being. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 34(4), 481-502. [ Links ]

42. Vallerand, R.J. (2007). A hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation for sport and physical activity. In M.S.D. Hagger & N.L.D. Chatzisarantis (Eds.), Self-determination theory in exercise and sport (pp. 255-279). Champaign, IL : Human Kinetics. [ Links ]

43. Weaver, M. A., & Chelladurai, P. (1999). A mentoring model for management in sport and physical education. Quest, 51, 24-38. doi: 10.1080/00336297.1999.10491666. [ Links ]

44. Wicker, P., Breuer, C., & Von Hanau, T. (2012). Gender effects on organizational problems-evidence from non-profit sports clubs in Germany. Sex Roles,66(1-2), 105-116. doi: 10.1007/s11199-011-0064-8. [ Links ]

45. Yusta (2015, November 29). Los despachos deportivos siguen todavía cerrados a las mujeres. Público. Retrieved from: http://www.publico.es/deportes/despachos-deportivos-siguen-todavia-cerrados.html. [ Links ]

46. Zamora, R., Muñoz-Cobos, F., Burgos, M.L., Carrasco, A., Martín, M.L., Ortega, I., Río, J., & Villalobos, M. (2012). Modelo de estadios de cambio: compatibilidad con relatos biográficos de mujeres que sufren violencia doméstica. Anales de Psicología, 28(3), 805-822. [ Links ]

![]() Correspondence:

Correspondence:

Andrea Perez-Rivases,

Facultat de Psicologia,

Departament de Psicologia Social,

Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

08193, Bellaterra, Barcelona, (Spain).

E-mail: andrea.perez@uab.cat

Article received: 09-08-2015

revised: 03-02-2016

accepted: 04-02-2016