Introduction

The introduction and maintenance of healthy habits is very important due to their influence on people’s behaviours, patterns, habits and actions since they contribute to their health improvement (Pullen, Noble & Fiandt, 2001; Sánchez-Ojeda, 2015). Physical activity (PA) leads to physical, social and psychological benefits regardless of age, which also increases the quality of life of the subjects engaged in it (Rosa, 2013; Romo & Barcala, 2012).

An active lifestyle has a positive impact on the individual’s self-esteem because of the subsequent higher level of independence although that really depends on the various health and social changes experienced during old age. Independence is linked to usefulness, decision-making, leisure activities, physical autonomy and health perception during old age. Consequently, PA enhances self-esteem (Herrera, Barranco, Melián, Herrera, Rodríguez & Mesa, 2004; López et al., 2006; Bergland, Thorsen and Loland, 2010; García, 2012) and is associated with positive self-esteem levels as it reinforces it (Tajfel &Turner, 1986; Eliezer, Major & Mendes, 2010; Troyano & García, 2013) and improves the quality of live of the elderly (Uribe, Padilla & Ramírez, 2004; Rodríguez, Valderrama & Uribe, 2010).

Self-esteem is defined as one’s psychological and positive perception of oneself involving relevant factors such as social support and functional autonomy (Masso, 2001; Nanthamongkolchai, Makapat, Charupoonphol & Munsawaengsub, 2007; Guerrero-Martelo et al., 2015), which may also be affected by gender and age (Escarbajal, Martínez & Romero, 2015: Goñi, Fernández-Infante & Zabala, 2012). Additionally, self-concept is strongly related to self-esteem, which is perceived as a series of someone’s beliefs about their own person, resulting from the analysis of personal experiences and self-esteem feedback, hence its multidimensional focus including cognitive parameters (self-image) as well as emotional (self-esteem) (González-Pienda, Núñez, González-Pumariega & García, 1997; Marsh & Craven, 2006; Rodríguez & Caño, 2012). There are different components such as the physical, academic, personal and social contexts (Esnaola, Infante & Zulaika, 2011). One instrument, Rosenberg’s Self-esteem Scale, allows experts to establish the connection between self-concept and self-esteem. It was validated for the Spanish population by Martín, Núñez, Navarro y Grijalvo, (2007).

PA can only be an efficient tool at increasing elderly people’s independence level if its type and intensity are kept under control by adapting physical exercises to each person’s characteristics (Lesende, et al, 2010). There is evidence that greater functional independence results in a higher quality of life for the subjects (Casals et al, 2015) since it reduces the possibility of health problems (Pavón, 2008). Therefore, Barber’s questionnaire proves very useful for the evaluation of dependence risks among the elderly (Barber et al, 1980; Lesende, 2005).

This research paper aims at analysing and understanding the impact of PA on self-esteem and dependence level in elderly people establishing a boundary between the control group (sedentary subjects) and the experimental group (active subjects). It is conducted based on a premise: the double hypothesis linking higher physical exercise level with more positive self-esteem and fewer dependence risks in old age.

Methodology

Participants

The whole sample included 168 people aged over 65 years, 84 of whom are classified as active (EG: experimental group) since they take part in PA and sport programmes organised by daytime centres in urban areas establishing a minimum 6 month-participation in the PA sessions as requirement. The remaining 84 people are totally sedentary as they do not engage in any sports or physical activities. A simple random sampling technique was used to select the sample avoiding any possible inconsistent results. A preliminary filtration of their physical state (elimination of subjects with a medium-high dependence level) as well as educational and cultural characteristics (exclusion of people with poor reading and writing skills) was performed to guarantee a satisfying level of autonomy before the different tests were carried out. A confidence level of 95% and margin of error of 3% were used.

The sociodemographic characteristics of the sample show that 76.8% of the subjects are women, all the participants are aged over 65 years (73.57±5.85), the marital status reveals that the majority of them are married (53%), followed by widows and widowers (26.8%), singletons (18.5%) and those who are divorced (1.8%). As regards PA practice level, 50% of the subjects do it, at least 2 hours every week whereas the rest remain sedentary taking no physical exercise whatsoever.

Instrument

Two questionnaires were used to analyse self-esteem and dependence risk self-perceived by elderly people, which also allowed for the collection of demographic data about the gender, age and marital status of the participants.

a) Self-esteem was evaluated using Rosenberg’s Individual Self-esteem Scale (1965), which analyses one’s self-perception as well as that of others. It consists of ten questions based on a Likert scale with four options (from 1 “I strongly disagree” to 4 “I totally agree”). Positive (items: 1, 3, 4, 6 and 7) and negative (items: 2, 5, 8, 9 y 10) self-esteem can be analysed separately. Previous versions of this scaled were applied to a sample with the results α=.79 (Fernández, 2002) and α=.89 (García and Rodríguez, 2009).

b) Dependence risk was evaluated using Barber’s test that consists of nine items involving a dichotomic answer (“true” or “false”). Every affirmative answer is worth one point as opposed to zero points for each negative answer. A total score of one or over suggests the presence of a dependence risk (Martínez & Rodríguez, 2005).

Procedure

The same researcher, who had previously been trained in the use of this scale, was in charge of administering the questionnaires. The permission and informed consent of all the adults participating in the study was also obtained. Some brief instructions were given to the participants and confidentiality was also guaranteed for their answers. Participation in the study was completely voluntary and no compensation was offered in exchange for any contribution. The research was conducted according to the ethical principles from the current Declaration of Helsinki in an effort to comply with all the highest professional safety and ethical standards for this type of projects.

Data analysis

First of all, Cronbach’s alpha which shows the reliability of the scale for this sample was obtained. Secondly, a descriptive analysis (average, standard deviation, variance, asymmetry and kurtosis) and scoring (percentiles) of the self-esteem scale were performed through the analysis of frequencies using the chi square test. Then, a descriptive and variance analysis (ANOVA) was carried out to describe the underlying connection between the practice of PA and dependence risk. Finally, the bivariate Pearson correlation descriptive analysis was performed and it generated a bilateral significance linking self-esteem variables, dependence risk and PA. All the data was handled anonymously using a series of codes and a confidence level of 95% for all the results (p <.05). The analysis was carried out using the statistical computer software SPSS, v. 21.0 for WINDOWS (SPSS Inc, Chicago, USA).

Results

Despite Rosenberg’s self-esteem scale being a validated tool, an exploratory factor analysis was performed resulting in the same factor structure as in the original version, which is taken into consideration for this study. The reliability test revealed a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the entire scale of .73, .78 for the positive self-esteem factor and .63 for the negative self-esteem factor. Table 1 shows data obtained from the descriptive analysis and the scaled score whose results allow the subjects to be classified according to the level of PA practice for a specific population group. In general, the results show higher positive self-esteem in elderly people with at least 2-hour-weekly PA practice (EG: 3.25 vs. CG: 3.14). Indeed, they obtained higher scores in questions involving negative self-esteem (CG: 2.23 vs. EG: 2.20).

Positive self-esteem is more appreciated by subjects from the EG, revealing higher scores compared to the CG considering, for instance, the items where they say that they perceive themselves as valuable as the others (3.25 vs. 3.07) or that they can do things as well as the others (3.23 vs. 3.00). Subjects from the CG only have higher scores when they say that they have some good things (3.36 vs. 3.30). However, the negative self-esteem analysis shows a different reaction pattern since subjects from the CG present higher scores compared to the EG, especially when they see themselves as a failure (2.04 vs. 1.75) or think they should show themselves more respect (2.50 vs. 2.46) although this tendency is reversed when they recognise that sometimes they feel a bit useless (2.36 vs. 2.52).

Table 1: Descriptive analysis and scaled scores of Rosenberg’s self-esteem according to the level of PA practice.

The analysis of variance (ANOVA) (Table 2) reveals significant differences: the active subjects (EG: 1.65±1.03) present a lower dependence risk than the sedentary ones (GC: 2.93±1.67).

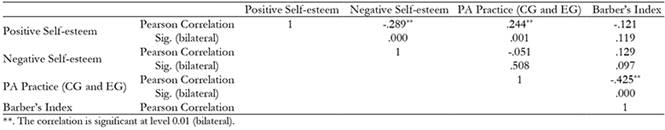

Convergent correlation (between factors: positive and negative self-esteem) and predictive correlation (between PA practice, self-esteem and dependence risk) were analysed. The results show that both positive and negative self-esteem dimensions have a significant and negative correlation (r = -.289, p ≤.001). Additionally, there is a positive and statistically significant correlation between PA and positive self-esteem (r =.244; p ≤ .01). Subsequently, an improved perception of oneself is produced in line with increased PA practice as subjects from the EG present greater self-esteem. That correlation also exists between PA and Barber’s index (r = -.425; p ≤ .001), which shows that the more PA (EG), the less dependence risk in old age (Table 3).

Discussion

The main goal of this study was to analyse and understand the impact of PA practice on self-esteem and dependence level in elderly people with a difference between the control group (sedentary subjects) and the experimental group (active subjects).

An acceptable general Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was obtained using Rosenberg’s self-esteem scale, which was slightly higher for the positive self-esteem factor than for the negative self-esteem. This data was similar to that obtained by Maroco & García-Marques (2013).

In this study, elderly people who engage in regular PA practice present higher positive self-esteem. As demonstrated in the study carried out by Troyano & García (2013) or García et al. (2012), the people with higher self-perceived self-esteem are certainly those who practise PA more frequently. In this study sedentary people present a higher negative self-esteem than active people, a tendency similar to that described by also described Teixeira et al. (2016), Elavsky et al. (2005) and Pereira et al. (2008).

PA is positively connected with the prevention of dependence risk as well as improved quality of life and acquisition of autonomy (González, 2003). In this study, elderly people from the EG present a lower risk than subjects from the CG, which is a confirmation of the results obtained by Poblete, Bravo, Villegas and Cruzat (2016). This correlation was confirmed not only in our study due to the positive impact of PA on positive self-esteem, but also with Barber’s index. In fact, a recent study by Battaglia, Bellafiore, Alesi, Paoli, Bianco and Palma (2016) showed that certain variables associated with mental health improved within the group of elderly people taking part in a training programme in contrast with the control group (sedentary people).

Conclusions and limitations

This study was not exempt from limitations. For example, some questions may have been misunderstood by the elderly although this possibility was under control since anonymity was at all time guaranteed and the subjects were always accompanied by researchers trained in the control and supervision of the instrument.

Regarding future lines of research, the sample used here could be extended or the study could be conducted from a longitudinal approach, which would bring more causality relationships.

As a conclusion, there is no doubt that PA presents a positive correlation with self-esteem and dependence risk in elderly people. Rosenberg’s self-esteem scale is a valid and reliable tool that gives researchers insight into one’s self-perception in old age. Barber’s test is a useful and adequate instrument for determining dependence risk within this part of the population.