Introduction

The advance in Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) over the last two decades has generated significant social change, offering unlimited opportunities and new possibilities for social interaction (Areepattamannil & Khine, 2017). However, excessive use of ICTs can lead to symptoms similar to behavioural addictions (López-Fernández, 2015).

Although there is no definitive agreement on the terminology used to investigate problematic Internet use (Caplan, 2010; Odaci & Çikrikçi, 2014), nor a unified definition and criteria that allow the diagnosis of this problematic use (Melchers, Li, Chen, Zhang, & Montag, 2015; Spada, 2014), two types have been distinguished: a) generalised, in which excessive amounts of money or time are invested without any specific objective, and b) specific, in which a certain online activity is carried out in an excessive or abusive way, such as online gambling, social networks or instant messaging.

The problematic use of mobile phones is conceived as the maladaptive use that can become a dependency and carry negative consequences at the family, work, academic and social levels (López-Fernández, 2015; Takao, 2014). This has been commonly regarded as generalised use (e. g., abuse of the Smartphone in general) and, to a lesser extent, as specific problematic use - e.g., abuse of instant messaging applications such as WhatsApp (López-Fernández, 2015).

Instant messaging is an Internet-based application that enables real-time communication through text, voice and video messaging (Wang, Ngai, & Wei, 2012). Its use has advantages such as facilitating interaction between co-workers and/or classmates, improving communication, increasing connectivity and improving family relationships, strengthening social and friendship relationships with others, and reducing isolation and loneliness, among others (Crosswhite, Rice, & Asay, 2014; Kim, Lee, & Kim, 2014; McDaniel & Coyne, 2016).

Nevertheless, excessive use of instant messaging can have multiple negative consequences, such as diminished academic performance, interruptions in work and reduced productivity, decreased communication among family members, increased jealousy, increased distrust and greater control of partners, and interpersonal conflicts, among others. (Baker & Carreño, 2016; Bhatt & Arshad, 2016; Caro, 2015; Galluch, Grover, & Thatcher, 2015; Grover et al., 2016; Lasén, 2014; Lin, 2012).

While there are tools that evaluate problematic mobile phone use, there is no specific instrument to analyse the impact of WhatsApp overuse. These types of scales are necessary because instant messaging has several different features compared to other applications that make this one more attractive to users. Features such as providing information about users' connection status, pop-ups when users receive a message, the immediacy of responses or the ability to have multiple simultaneous conversations -individually or in groups- (Mesch, Talmud & Quan-Haase, 2012; Wang et al., 2012). These features enable these tools to be used differently than others. WhatsApp is one of the most popular and widely used instant messaging applications for Smartphones (Aharony & Gazit, 2016; Faye, Gawande, Tadke, Kirpekar, & Bhave, 2016; Montag et al., 2015). With total of 1200 million active users in January 2017 (Statista, 2017), it is the leading instant messaging service in 109 countries, including Brazil, India, Mexico, Argentina, Russia, Germany, Spain and the United Kingdom (Schwartz, 2016). Therefore, the aim of this study is to develop and validate a specific scale to assess the negative impact of such use in different areas, entitled WhatsApp Negative Impact scale (WANIS). This scale evaluates novel aspects such as the use of WhatsApp to control partners and intimate relationships. However, while this scale could be used to evaluate any other instant messaging tool, the choice was made to focus it on the use of WhatsApp because its widespread popularity among the population makes it a familiar tool.

Study 1

Method

Participants

A total of 95 participants were involved in the pilot study for the development of the scale. Of the total, 60% were women studying at the University of Murcia, Spain. Seventy point three percent were students of the Psychology Degree, 20.9% were students of the Dentistry Degree, 7.7% were students of the Occupational Therapy Degree and finally 1.1% was studying Dramatic Art. The total sample aged between 17 and 27, (M = 21.34, SD = 2.11). According to academic year, 9.7% were from the first, 1.1% from the second, 72% from the third, 15.1% from the fourth and 2.2% from the fifth.

Procedure

An initial list of 69 items was compiled to assess instant messaging addiction based on observation of behaviours (individual and group) and research on instant messaging usage and its impact on different areas of everyday life (Bhatt & Arshad, 2016; Goodman-Deane, Mieczakowski, Johnson, Goldhaber, & Clarkson, 2016; Grover et al., 2016; Lin, 2012). The items were grouped into five categories: abuse, social consequences, family consequences, effects on the couple, academic consequences. This first draft of the questionnaire was evaluated by six judges who were experts in Internet addiction. Each judge assessed the suitability of the item in the category to which it belonged by scoring on a Likert scale from 0 (None) to 3 (Much). The interjudge agreement index was .95.

After the experts’ judgment, students completed the questionnaire in a thirty-minutes session in the presence of a member of the research team (clinical evaluation expert). Participants did not receive any incentive to participate in the study. Ethical principles of research with human beings were respected, ensuring the confidentiality of the participants.

Data Analysis

Mean and standard deviations of all items for all six judges were obtained. The items that obtained an average score of less than 2 points and/or a standard deviation greater than 1 were eliminated (range 1 to 5 points), except in those cases in which the judges advised to re-elaborate them for their informative value. In addition, an item analysis was carried out, calculating the basic statistics and the corresponding uniformity indexes. Those items whose homogeneity index was between .30 and .70 were selected (Crocker & Algina, 1986). Data analysis was performed using SPSS (V. 20.0.).

Results

After collecting the judges' assessments four items were deleted. The scale was made up of 65 items in the same format as the original scale. The 65 items were applied to the convenience sample and an analysis of items was performed, resulting in a definitive scale of 40 items with homogeneity indexes greater than .30.

Study 2

Method

Participants

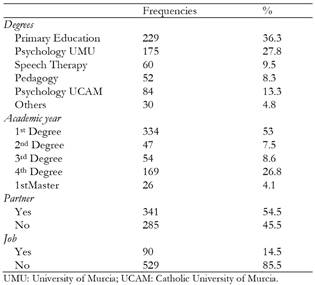

This group consisted of 630 participants aged between 18 and 62 (M = 21.23; SD = 4.32). Other socio-demographic characteristics can be seen in Table 1. The percentage of missing data was 1.45% and there was no floor and/or ceiling effect on the total scale (0%).

Instruments

Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale (GPIUS2, Caplan, 2010; Gámez-Guadix, Orue, & Calvete, 2013). It consists of 15 items in Likert format, from 1 (totally disagree) to 6 (totally agree). This scale measures five dimensions: Preference for online social interaction (α =.90); Mood regulation (α =.78); Cognitive preoccupation (α =.76); Compulsive Internet use (α =.84); and Negative outcomes (α =.79). All reliability coefficients were calculated on the sample used in this study, and for full scale α = .91.

Psychological Well-being Scale (EBP; Sánchez-Cánovas, 1998). It consists of 65 Likert items from 1 (never or almost never) to 5 (always). They are grouped around 4 dimensions: subjective psychological well-being, material well-being, work well-being, and relationships with the couple. Only the dimensions of subjective Psychological Well-being (α =.95) and Material Well-being (α =.91) were administered to the group.

Procedure

The scale was administered to a convenience sample made up of students of different Degrees from the University of Murcia and the Catholic University of Murcia, Spain. After obtaining informed consent from participants, students completed the questionnaire in a one-hour session in the presence of a member of the research team (clinical evaluation expert). Participants did not receive any incentive to participate in the study. During its development, the ethical principles of research with human beings were respected, ensuring the confidentiality of the participants. The ethics committee of the University of Murcia evaluated and approved this research.

Data analysis

An Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was performed using the unweighted least squares estimation method on a matrix of polychoric correlations. Parallel Analysis was used along with a good adjustment index (GFI >.95) and the root of the residual root mean square (RSMR < .08) for factor selection. Promax rotation was used to rotate the factor solution to simple structure. FACTOR v. 10.0 was used for this analysis (Lorenzo-Seva & Ferrando, 2013).

The internal consistency of the resulting dimensions was calculated with Cronbach's alpha coefficient. Empirical validation was tested with the Pearson correlation and Student t to test differences between groups.

Results

Descriptive analyses of items

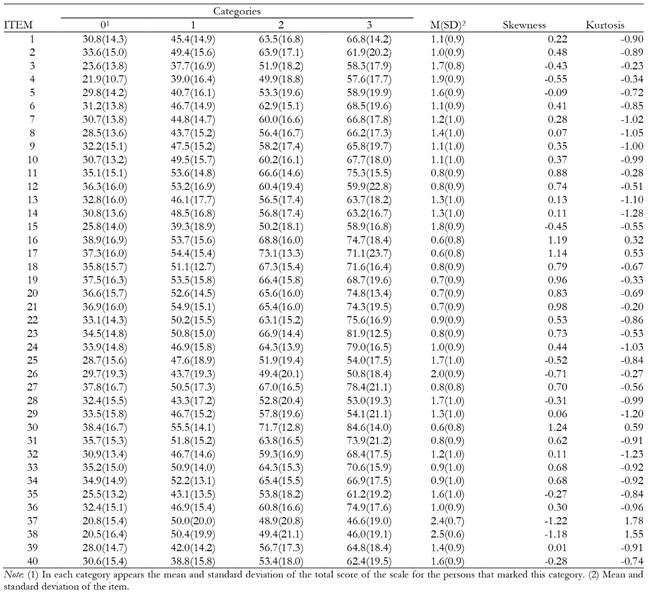

Table 2 shows the analysis of the 40 items selected for the sample of 630 cases. The average of participants according to category is increased as expected by the model, since participants with higher total scores must score a higher category. However, items 37 and 38 do not maintain this pattern. Then, both items were eliminated of the scale.

The final scale consisted of 37 Likert type items. The answer values were 0 (totally disagree), 1 (disagree), 2 (agree) and 3 (totally agree). The scale does not have any inverse items. The total score of it is obtained through the sum of the items.

Structural validity

The EFA of the remaining 38 items revealed that a three-factor solution was most appropriate for interpreting the WhatsApp Negative Impact scale. However, item 13 was removed from the resulting structure for not obtaining a structural coefficient greater than 0.30 in all three factors. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) sample adequacy measure was high (0.94) and Bartlett's sphericity test was highly significant, χ2(703) = 11273.8, p < .001.

The three resulting factors (GFI =.99, RSMR =.05) together accounted for 56.47% of the total variance (Table 3). The first factor, Negative Consequences of WhatsApp Use (NCWU), explained 42.58% of the variance. The second factor, Controlling Intimate Relationships through WhatsApp (CIRW), explained 8.01%. And finally, the third factor, Problematic Use of WhatsApp (PUW), explained 5.88% of the variance.

Reliability

Scores on the WANIS were found to be highly reliable, considering that the alpha coefficient was .95. In the NCWU, the reliability coefficient was high (α = .93); in the CIRW, the alpha coefficient was. 85; and finally, the alpha coefficient of the PUW was .87.

Convergent and discriminating validity

Convergent validity was found by correlating each of the factors and WhatsApp scale's total score with the subscales and GPIUS2 total score (Table 4). The results showed mean, positive and significant correlations (p < .01), indicating that the instrument had good convergent validity.

Discriminant validity was obtained by correlating each of the factors and the WhatsApp scale's overall score with the subscales of ‘Subjective Psychological Well-Being’ and ‘Material Well-Being’ that make up the Psychological Well-Being Scale (EBP). All correlations were negative and significant (p < .01), indicating that the instrument had good discriminant validity (Table 5).

Empirical validity

There were statistically significant differences according to sex, both in the WhatsApp Negative Impact total scale and in the PUW, with the mean reached by women being higher than men (Table 6).

The correlation of the scale's overall score with age was negative and significant, although very low (r = -.13, p = .001). The younger the student's age, the more NCWU (r = -.08, p =.044); the more CIRW (r = -.08, p =.047); and the more PUW (r = -. 19, p < .001).

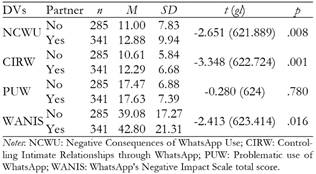

Statistically significant differences were found among students with or without a partner, both on the WANIS and on NCWU and CIRW, with the mean reached by students with a partner being higher (Table 7).

Finally, statistically significant differences were found depending on whether or not they had a job. Unemployed students achieved higher average scores in NCWU, PUW, and the WANIS (Table 8).

Table 7: Comparison of means on the WhatsApp Negative Impact scale (WANIS) based on whether or not they have a partner.

Discussion and conclusion

The purpose of this study was to create a scale to evaluate the negative impact of WhatsApp on users (WANIS), since there are no tools available at the moment, and it is becoming increasingly necessary to have a tool to know the possible negative consequences derived from the continued use of this instant messaging application. To this end, a list of items was compiled based on the observation of the behaviours (individual and group) of WhatsApp users and of previous studies on the impact of instant messaging in different areas of everyday life (Bhatt & Arshad, 2016; Goodman-Deane et al., 2016; Grover et al., 2016; Lin, 2012).

The EFA disclosed that the three-factor solution was most appropriate for interpreting the scale. The three resulting factors together accounted for 56.47% of the total variance. Factor I, Negative Consequences of WhatsApp Use, refers to the possible negative effects of WhatsApp use on social, family and academic performance. Factor II, Controlling Intimate Relationships through WhatsApp, mentions both the control of partners and friends through WhatsApp, and the jealousy and suspicions that could arise among partners as a result of using this application. Finally, Factor III, Problematic Use of WhatsApp, reports on the potential dependency on WhatsApp by users manifested through individual behaviours and behaviours with friends, family or in the academic environment.

WhatsApp Negative Impact Scale assesses the major issues that can result from excessive use of this application, such as controlling people in your immediate environment and partner, jealousy and mistrust, WhatsApp's interference in social and family relationships, the negative impact on academic performance, and the need to constantly use WhatsApp to the detriment of other activities.

As for psychometric properties, the scores of the questionnaire designed had a high reliability, maintained by analysing each dimension separately, indicating that the items of each factor are closely related. The scale also had good convergent and discriminating validity after being compared with instruments that evaluated the problematic Internet use and psychological well-being. This indicated that high scores on the WhatsApp Negative Impact scale were associated with high scores in problematic Internet use and at the same time low scores in psychological well-being. Thus, it is a psychometrically appropriate instrument to measure WhatsApp's negative impact on users and it can be a reference and useful tool in future research on this construct.

Other variables analysed were the relationship between WhatsApp's Negative Impact on Gender, Age, Marital and Employment Status. Regarding sex, statistically significant differences were found in WhatsApp's Negative Impact and PUW, with women scoring higher than men. This suggests that women may abuse WhatsApp more, a finding that matches Montag et al. (2015). Women, by using more instant messaging, could abuse this tool more and may experience a greater negative impact.

In terms of age, it was found that the lower the age, the greater the negative impact of WhatsApp, the greater the negative consequences derived from the use of this tool, the greater the control of intimate relationships through this application was made and the greater the problematic use of WhatsApp was experienced, although due to the low correlation, the results need to be interpreted with caution. This could be because young people are more vulnerable to addiction in general and to problematic Internet use in particular, possibly because they are less self-controlled, less self-regulatory and more exposed to the network and new technologies (Jacobson, Bailin, Milanaik, Adesman, 2016; Wang, Fan, Tao & Gao, 2017). In addition, young people are less aware of the negative consequences of their actions, which would lead them to continue with addictive behaviours and experience an increasing negative impact. Finally, young couple relationships are often less stable and durable. This, together with the insecurity that characterizes the young, would result in the need for greater control of the couple, with WhatsApp being a tool that can be used for this purpose. This coincides with the results found by Caro (2015). However, further research should be carried out into the direction of these results given the low correlations obtained.

College students with a partner also experienced greater negative impact from WhatsApp, more negative consequences due to the use of this tool, and more control over their intimate relationships through this application. These students could use WhatsApp to keep in continuous contact with their partners and to control what they do, where they are, when they are connected and when they are not, why they don't talk to them despite being connected, and so on. This monitoring and control of the couple through WhatsApp could have a number of negative consequences for users. Our results are in line with previous studies that indicated that the use of instant messaging contributes to partner problems, control conflicts, jealousy, possession, mistrust and suspicions (Lasén, 2014; Lin, 2012).

In terms of employment status, unemployed students scored higher than those who had work in WhatsApp's negative impact, negative consequences and problematic use. College students with jobs would have to combine education with employment, so they may have been busier and had less time to use WhatsApp. Instead, unemployed people may have more free time to connect to WhatsApp, and may be more likely to develop problematic Internet usage and experience more negative consequences and greater negative impact due to their use of WhatsApp.

This study has a series of clinical implications, highlighting that it is an innovative, valid and reliable tool to evaluate the problematic use of WhatsApp, as well as the negative consequences of its use and the control exercised by users of their intimate relationships through this application. Therefore, it is an innovative tool, since so far there is no tool of this kind in previous research which allows the early detection and prevention of the Negative Impact of WhatsApp. Also, early intervention in people who suffer from excessive use of WhatsApp would result in less professional, academic, family, social, and partner deterioration that may result from its use, so improving the psychosocial well-being of these users.

Limitations of the study include, on the one hand, the use of a sample for convenience, since the selection of participants was not randomized. Also, a confirmatory factor analysis was not performed to verify that the three-factor solution was the most appropriate to interpret WhatsApp's Negative Impact Scale. It may be interesting in future studies to apply this scale to clinical populations, such as people with some kind of addiction, whether chemical or behavioural, to investigate whether they experience a greater negative Impact from WhatsApp. It may also be attractive to administer this scale to people diagnosed with social anxiety, in order to evaluate the impact of WhatsApp on these people, as it is possible that this form of communication can be used as a substitute for face-to-face interaction.