Introduction

The recent appearance of online social networks and the generalised use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) have given rise to new virtual forms of social interaction or cyberinteraction. For teenagers, having a profile and using social networks is very important. This generation interacts with their peers digitally to connect, communicate, develop and maintain relationships, so if someone doesn't use social networks is practically isolated (Dhir, Puneet, & Rajala, 2018). In this sense, fifteen per cent of adolescents from 9 to 10 years old have a profile on social networks, and this percentage rises to 83% among older adolescents. In addition, studies reveal that 42% of boys and 50% of girls from 13 to 16 years old visit a profile on a social network daily, and 20% of boys and 40% of girls post photos and videos daily (Garmendia, Jiménez, Casado, & Mascheroni, 2016).

These virtual spaces have brought a change in how teenagers interact with their sexual partners (Lippman & Campbell, 2014), thereby setting up a new scenario in which a range of sexual behaviours can be carried out, such as engaging in sexting. Sexting is a new phenomenon that consists in exchanging explicit or provocative sexual material (text messages, photos and videos) using smart phones, the Internet and/or social networks (Chalfen, 2009). According to INTECO (2011), this behaviour is characterised by three criteria: (1) an initial willingness without the presence of coercion, suggestions or extortion; (2) the creation of materials with a highly erotic or sexual content; and (3) the use of electronic devices as a means to send, receive and forward the material.

Even though receiving and sending images or videos of a sexual nature is not new (Delevi & Weisskirch, 2013), the use of electronic devices to create and disseminate such contents means that sexting has its own particular characteristics. The first of these has to do with the absence of risk perception about the negative consequences that this behavior may cause (Alfaro et al., 2015). This material is frequently sent as a gift to a partner or as a flirting strategy without taking into account the loss of control over the content if the couple splits up, the device is lost or stolen, a third party gains access to the device without the owner's consent, etc. (Van Ouytsel, Van Gool, Walrave, Ponnet, & Peeters, 2017). The second is related to the immediacy of communication (INTECO, 2011). Today's functional, portable and economical technology means that an immediate impulse can easily become a reality that is impossible to stop, and this immediacy makes reflection more difficult. The third characteristic concerns the absence of control over the use and forwarding of the content that has been sent (Ferguson, 2011). The photographs or videos can be sent out to a large number of people who, in turn, can resend them a countless number of times.

Several studies have determined that sexting is a phenomenon that begins at early ages and its incidence increases with age (Mitchell, Finkelhor, Jones, & Wolak, 2012). According to Dake, Price, Maziarz and Ward (2012), only 3% of 12-year-olds engage in sexting while at the age of 18 this percentage rises to 32%. With regard to sex, at present there are strong discrepancies among the results from different studies. Some of them conclude that boys are more likely to sext than girls (Strassberg, McKinnon, Sustaíta, & Rullo, 2013). In contrast, other research has shown that this practice is not influenced by sex (Dake et al., 2012; Gámez-Guadix, de Santisteban, & Resett, 2017). Several studies, however, have concluded that the teenagers who engage more in sexting behaviours are those who are in a steady relationship with a partner (Van Ouytsel, Ponnet, Walrave, & d’Haenens, 2017).

Today, the sending and receiving of photos or videos of a sexual nature is increasing significantly among teenagers. International studies determine that the prevalence of sexting is somewhere between 23.1% and 31.7% for receiving photos or videos and between 12.5% and 16.8% for sending sexual contents (Madigan, Ly, Rash, Van Ouytsel, & Temple, 2018). In Spain, 4% of youngsters aged between 10 and 16 admitted taking photos or recording videos of themselves in a sexy pose using their mobile phone, while 8.1% report receiving pictures or videos on their phone from people they know posing in sexy postures (INTECO, 2010). Another more recent study by Gámez-Guadix and colleagues (2017) determines that the overall prevalence of sexting was 13.5%. The prevalence was 3.4% at 12 years old and increased to 36.1% at 17 years of age, showing a growing and significant linear trend. In Spain, there is not a specific law regarding sexting. For this reason, in order to increase the minors’ protection, some revisions of general laws have been developed such as one presented in December 2010 (Organic Law 5/2010, June 22) that replaced another from the Criminal Code (Organic Law 10/1995, November 23). The legislative response towards sexting is included in the article 189 of the Criminal Code in which the production, distribution and possession of sexual contents can be considerate, production and distribution of child pornography, in case sexual contents were referred to explicit sexual expressions in minors. However, in this case, minors are producing and distributing sexual contents and, at the same time, they are the own protagonists. For this reason, applying a law adjusted to other situations is difficult. This ambiguity underlies the belief of Spanish adolescent in which they consider that sexting behaviors are legal. This may explain the higher prevalence of this practice.

Teenagers who engage in sexting expose themselves to a series of cybernetic risks, including: physical and geolocalisation risks due to the pictures or videos may contain elements that help to identify the people that appear in them or facilitate their localisation (INTECO, 2011); cyberbullying, harassment and stalking carried out among minors by means of an electronic device (Van Ouytsel, Van Gool, Ponnet, & Walrave, 2014; Ybarra & Mitchell, 2014); sextortion, which is a form of blackmail in which somebody uses a person’s videos or photos of a sexual nature to obtain something from them under the threat of disclosing the material (Wolak, Finkelhor, & Mitchell, 2012); and grooming, which consists of a set of strategies that an adult uses in order to win over a youngster’s trust and gain concessions of a sexual nature (INTECO, 2011).

The seriousness of the consequences that such behaviours have on the adolescent’s overall development together with its high prevalence show the need to draw up and implement preventive strategies (Del Rey, Ojeda, Casas, Mora-Merchán, & Elipe, 2019; INTECO, 2011). In order to produce them correctly, however, it is first necessary to know which factors influence on the initiation and maintenance of this practice (Alonso, Rodríguez, Lameiras, & Martínez, 2017). In this regard, Cooper, Quayle, Jonsson and Göran (2016) determine the existence of four broad topics that would cover the main ambimotivations underlying engagement in sexting: flirting with and/or attracting the partner's attention, being in a steady relationship, seeing sexting as an experimental phase of adolescence, and being put under pressure by the partner or by friends. In the Spanish context, girls’ main reasons for sexting are to have or maintain an emotional relationship, whereas the boys’ justifications are to achieve a sexual relationship (Alonso-Ruido, Rodríguez-Castro, Lameiras-Fernández, & Martínez-Román, 2018; Rodríguez-Castro, Alonso-Ruido, Lameiras-Fernández, & Faílde-Garrido, 2018). Moreover, several studies have focused on examining attitudes towards sexting (Samimi & Alderson, 2014). The results show that teenagers who have more positive attitudes towards sexting present a greater number of sexting behaviours, with a greater risk associated with the erotic content of the material that is sent or received (Hudson & Fetro, 2015; Rodríguez-Castro, Alonso-Ruido, González-Fernández, Lameiras-Fernández, & Carrera-Fernández, 2017).

The current scientific literature frames an understanding of sexting behaviours among adolescents within the dual systems model of risk-taking. The Dual Systems Model posits the idea that risk-taking results from both logical reasoning and psychosocial factors (Steinberg, 2008). Impulsiveness is a spontaneous tendency to act on a whim, displaying behaviour characterized by little or no reflection, planning, or consideration of the consequences. This theory determines that risk behaviours and an impulsive decision-making process of adolescents seem not to be related to a minor reasoning, rather a scarce maturity of brain regions responsible for conscious behavior (Steinberg, 2008; Steinberg et al., 2008). Regarding this evolutionary pattern, emotions would play a more important role on some behaviours than reasoning on account of the executive functioning is not mature enough to manage emotions (Rhyner, Uhl, & Terrance, 2018; Steinberg, 2008). In this sense, adolescents are more sensitive to reward compared to punishment and, consequently, prefer immediate benefits that sexting generates than later potential damages. One review conducted by Cruz and Soriano (2014) determines that engagement in sexting is more frequent among those teenagers who are more impulsive to seek new sensations.

In line with the importance of the psychosocial factors mentioned in the Dual System Model, other research has focused on analysing the influence of certain variables, such as self-esteem and sexism. According to Rosenberg (1965), self-esteem is a variable reflecting the general attitude a person has about personal value. The self-esteem level would be decisive due to this determines social relations based on how people self-perceive themselves. Low self-esteem has been associated with certain sexuality problems, including engaging in sexual risk-taking (Jackman & MacPhee, 2015) and the experience of lasting consequences associated with sexting practice (Scholes-Balog, Nicole Francke, & Sheryl Hemphill, 2016). However, current results regarding self-esteem display a number of discrepancies from one study to another. Some conclude that teenagers who engage in sexting present lower levels of self-esteem (Ybarra & Mitchell, 2014). In contrast, other research has determined that this variable does not have any influence on the sending or receiving of such contents (Hudson & Fetro, 2015).

Sexism has typically been conceptualized as a reflection of hostility toward women and includes two components reflecting hostile and benevolent attitudes (Glick & Fiske, 1996). Benevolent sexism includes stereotypically attitudes and restricted roles that are subjectively accepted and also tend to elicit behaviours typically categorized as prosocial or intimacy-seeking. One of the components of this type of sexism is the myths of romantic love, “a set of socially shared beliefs about the allegedly true nature of love” (Yela, 2003, p.264). These myths are absurd fictitious and irrational and are collectivized differently due to the cultural beliefs regarding gender roles (Nava-Reyes, Rojas-Solís, Greathouse, & Morales, 2018). Conversely, hostile sexism shares the negative affective charge of traditional sexism and is a stereotyped and negative view of women as a consequence of the greater social power of men. In this context, sexist attitudes seem to significantly influence the resending of these contents without the original sender's express consent (Morelli, Bianchi, Baiocco, Pezzuti & Chirumbolo, 2016). Sexism, based on the myths of romantic love, is related to the belief that women have to adopt a submissive role and obey partners’ demands. Initially, this attitude facilitates an explicit request to send sexual material by man that is answered by woman regardless of a total conviction (Temple & Choi, 2014). After that, man may distribute this sexual material to punish a supposed disobedience or insolence of women, getting inside cyberbullying (Quesada, Fernandez-González, & Calvete, 2018).

Given the lack of risk perception in the use of social networks that characterizes adolescents and the impact that the practice of sexting can have on them it is necessary to analyse the variables and personality traits that distinguish adolescents who practice sexting from adolescents who do not practice sexting. So, the first aim of this study is to estimate the prevalence of sending and receiving sexual material among Spanish teenagers, distinguishing between figures for males and females. The second aim is to analyse the attitudes towards sexting according to whether participants engage in sexting or not. Finally, the third aim is to analyse the predictor variables of the sexting behaviours. To do so, an analysis is performed to determine how attitudes, self-esteem, impulsivity and sexism are related to engagement in sexting.

Method

Procedure

Firstly, we developed the Spanish adaptation of the instruments that were originally written in English (Sexting Behaviours Scale and Motivations for Sexting). Impulsivity Scale, Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale and Myths, Fallacies and Mistaken Beliefs about the Ideal of Romantic Love Scale had a Spanish version and we use that. A Spanish psychologist with a high level of proficiency in English carried out a translation. This preliminary translation was reviewed by two graduates in English philology and when their consensus was lower than 85%, we included their suggestions. An expert panel of two educational psychologists assessed the revised version and provided alternative expressions in cases in which the wording of some item was not considered to be the most suitable. In the second phase, the corrected version of the different scales was administered to a small group of people in a pilot study.

After obtaining the necessary permissions from the Conselleria de Educación, Cultura y Deportes de la Generalitat Valenciana (Regional Government), an appointment was made with the counsellor at each school in order to explain the aims of the research and to request their participation. We contacted with various educational centers of the Valencian Community to collect a representative sample. For this suppose, in selecting the centers, we followed a convenience sample procedure according to the type of school (public or private) and the location (Valencia or Castellón de la Plana). Thus, in the final sample, 76.3% of the participants (n = 598) studied in a public school and 23.7% (n = 187) in a private school. In addition, 41.7% of the participants live in Valencia (N = 327) and 58.3% live in Castellón de la Plana (N = 458).

Pupils were then given an authorisation to be filled in by their parents and/or legal guardians. After having obtained all the permissions, the battery of questionnaires was administered. The evaluation sessions were held at the time each school deemed most convenient during teaching hours. To do so, a member of the Salusex research team attended each class and administered the instruments to the groups as a whole, settling any doubts that might arise during the process. The instruments were administered (whenever possible) in electronic format in the computer classrooms available at each of the schools, by accessing the platform where the questions had been posted. In schools that did not have the necessary IT infrastructure, the same battery of instruments was administered in pencil and paper format. The average time per assessment was 40 min, 5 of which were devoted to establishing rapport with the participants. However, in order to verify nonexistence of differences between both groups we have done some statistical analyses. The first group that filled the questionnaire in paper-pencil contains 53.7% of men and 46.3% of women from 12 to 18 years old (M = 14.34; SD = 1.64). The second group that filled the questionnaire on the computer involves 50.6% of men and 49.4% of women, between 12 and 18 years old (M = 14.53; SD = 1.59). There are not statistical significant differences based on gender (X 2= .763; p = .390), age (t = -.1.616; p = .107) or being in a stable relationship (X 2= .048; p = .856). Participants were assured at all times that, their answers were voluntary and anonymous, thereby guaranteeing their privacy and reducing as far as possible any social desirability effects. Recruitment of participants was carried out between September 2017 and September 2018.

Sample

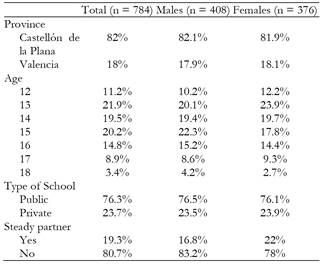

The sample consists of a total of 784 teenagers, 408 boys (52%) and 376 girls (48%), between 12 and 18 years of age (M = 14.44; SD = 1.61), all of whom were studying at three educational centres in the provinces of Valencia and Castellón, Spain. Thus, 19.6% of the participants were studying the first year of compulsory secondary education (in Spanish, ESO - 12 years old), 22.7% were in the second year of ESO, 19.9% in the third year, 19.1% in the fourth year, 4.7% were studying a basic vocational training course, 3.8% were in middle vocational training, 8.2% were in the first year of their Baccalaureate studies and 2% were finishing secondary education in the second year of Baccalaureate. When the evaluation was conducted, 19.3% reported being in a steady relationship with a partner. Details of the sociodemographic data are shown in Table 1.

Instruments

Ad-hoc sociodemographic questionnaire. Participants answered several questions about sex, age, province where they resided, academic year, type of school and whether they were in a steady relationship with a partner.

Sexting Behaviours Scale (Dir, Coskunpinar, Steiner, & Cyders, 2013). This instrument evaluates the prevalence and the frequency of engagement in sexting behaviours. It consists of 11 items (for example, “how often have you sent provocative or suggestive pictures or messages over the internet (i.e. Facebook, e-mail, MySpace, etc.)?”): five of them are to be answered on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 “Never” to 5 “Often/daily”, one open-answer item and one multiple-choice item. In this study, a Cronbach’s alpha of .78 is obtained.

Motivations for Sexting (Drouin & Tobin, 2014). This is an instrument that evaluates the motives for engaging in unwanted sexting with a committed partner. It consists of 10 items (for example, “I wanted intimacy” or “I wanted to be like my friends”) that ask about the motives related to oneself, one's partner, the peer group and society at large. For the purpose of this study, the items have been slightly modified to evaluate the motivations for engaging in sexting with a committed partner or other person. Respondents answer on a 5-point Likert-type scale that ranges from 1 “never” to 5 “always”. In this study, a Cronbach’s alpha of .81 is obtained.

Sexting Attitudes Scale (Weisskirch & Delevi, 2011; Rodríguez-Castro et al., 2017). This scale consists of 15 items (for example, “sexting is a regular part of romantic relationships nowadays”), with 6-point Likert-type answers, which evaluate three dimensions of attitudes towards sexting: fun and carefree; perceived risk; and relational expectations. Scores range between 10 and 90 points. The higher the score is, the more favourable the attitudes towards sexting will be. The Cronbach’s alpha of the factors on the original scale was .89, .82 and .78, respectively. In this study, the internal consistency for the overall scale was .77.

Impulsivity Scale (Plutchik & Van Praag, 1989; Alcázar-Córcoles, Verdejo, & Bouso-Sáiz, 2015). This instrument consists of 10 items (for example, “do you find it difficult to control your emotions?”) that describe different situations related to the degree of control over impulses. Respondents answer on a Likert-type scale with four alternatives that range from 0 “never” to 3 “nearly always”. Scores range from 0 to 45 points. The higher the score is, the greater the level of impulsivity will be. The adaptation of the scale in a sample of Spanish-speaking teenagers presents good reliability indices (α = .73). In this study, a Cronbach’s alpha of .83 is obtained.

Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965; Martín-Albo, Núñez, Navarro, & Grijalvo, 2007). This instrument consists of 10 items that evaluate self-esteem (for example, “I feel that I have a number of good qualities”), understood as referring to feelings of personal worth and respect towards oneself. Respondents answer on a Likert-type scale with four possible answers that range from 1 “totally disagree” to 4 “totally agree”. Scores range between 10 and 40 points. The higher the score is, the greater the level of self-esteem will be. The Spanish adaptation presents good internal consistency (α = .88) and a test-retest value, obtained by means of the Pearson correlation, of .84.

Myths, Fallacies and Mistaken Beliefs about the Ideal of Romantic Love Scale (Luzón, Ramos, Recio, & de la Peña, 2011). The scale consists of 9 items (for example, “love is very important because…” or “for love I would be able to…”) that evaluate sexist attitudes relating to four myths about romantic love: love can do everything, true love is predestined, love is the most important thing in life and requires total submission and love implies possession and exclusivity. From a group of statements, where only one answer is correct and which vary in number according to each item, respondents must choose the one that they agree. Renowned psychologist of education and gender violence agreed the right answer in each affirmation. The total score is calculated by adding one point for each incorrect answer, thus resulting in a value that ranges between 0 and 9. The higher the score is, the greater the sexist attitudes will be. In this study, an internal consistency of .65 is obtained.

Data analysis

Prevalence figures were estimated by calculating percentages and some descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation). Differences according to sex were calculated by means of the chi-square statistic. The Student t test for independent samples was used to determine the existence of any differences in attitudes towards sexting among people who sext (n = 198) and those who had never engaged in this practice (n = 662). The effect size was calculated using the Cohen d coefficient. Lastly, for the analysis of the explanatory variables of the initiation and maintenance of sexting behaviours, a Pearson correlation analysis and binary logistic regression analysis were performed. In order to calculate the global score in each scale, we have recoded those scores that were inverse. The statistical analyses were conducted with the statistics program IBM SPSS Statistics 24.

Results

Prevalence and motivations

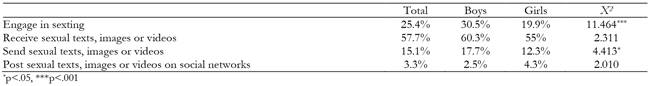

In this study, we consider the practice of sexting as involving the sending of messages, images or videos with a sexual content which show the body of the sender or the receiving of this kind of material by a partner or person with whom he or she is flirting. The prevalence of sexting was determined by taking into account those who had answered the question “On average I usually sext with…” in the questionnaire of Dir and colleagues (2013) with any response other than “I do not sext”, that is, those who explicitly reported sending or receiving sexual content by people who attract them, people with whom have dates or a stable relationship. As can be seen in Table 2, the results showed that 24.4% (n = 198) have engaged in sexting at some time, with an average of 2.32 people (SD = 2.70). Of all the people who reported having engaged in sexting, 56.3% did so with people with whom they had a steady relationship, 24.4% with acquaintances they felt attracted to, 12.6% with people who they were dating, and 6.7% with other people. In terms of sex, it should be highlighted that boys sext more than girls (30.5% vs. 19.9%), these differences being statistically significant (p = .001).

As regards the sending of sexually explicit images or videos of a generic nature, in which the teenager’s own body does not necessarily appear, results showed that 15.1% (n = 118) have sent this kind of material. Of the total number of teenagers who reported having sent such contents, 78% do so on a very sporadic basis, 14.4% do it occasionally, 5.1% reported doing it often and 2.5% stated that they frequently engaged in this kind of activity.

As regards the reasons why they engaged in such behaviour, the teenagers were given a list of motives, drawn up by Drouin and Tobin (2014), where they had to answer each item independently. The motives that obtained the highest percentages are: wanting to make the relationship with the boy or girl they like more intimate (11.6% in boys and 11.8% in girls), because their partner had explicitly asked them to do so (10.5% in boys and 9.4% in girls) because they just felt like doing it or had no apparent motive for doing so (9.9% in boys and 7.1% in girls) or out of boredom (9.2% in boys and 4.7% in girls).

Attitudes towards sexting

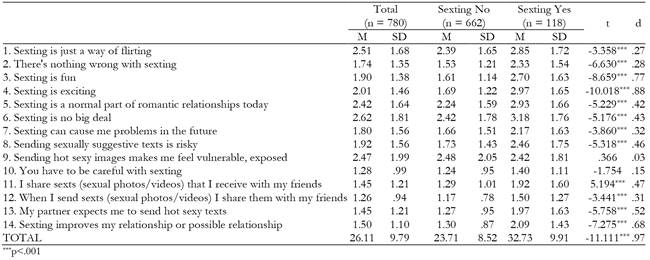

In an analysis performed to determine whether there are any differences in teenagers’ attitudes towards sexting, depending on whether they engage in this behaviour or not (see Table 3), those who sext obtain statistically significant higher scores than those who do not (23.71 vs. 32.73; p = .001). When we perform a detailed analysis of each item, statistically significant differences are observed in all the items of the instrument, with higher scores among the teenagers who engage in sexting, except for items 9 “Sending hot sexy images makes me feel vulnerable, exposed” (2.48 vs. 2.42; p = .715) and 10 “You have to be careful with sexting” (1.24 vs. 1.40; p = .080), where no significant differences are found. The effect sizes present magnitudes that range between small, medium and high values, with a minimum of .27 and a maximum of .88. It should be noted that the analyses performed according to sex determined that boys (M = 27.93, SD = 10.45) present more positive attitudes towards sexting than girls (M = 24.17, SD = 8.63), these differences being statistically significant (t1,707 = 5.274, p = .001).

Explanatory variables of sexting behaviour

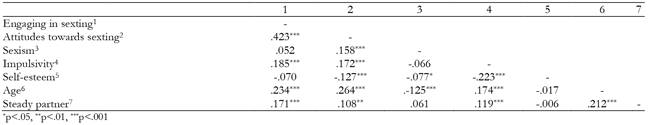

As can be observed in Table 4, the Pearson correlation analysis reveals the existence of statistically significant positive correlations between engaging in sexting and four of the six variables analysed: attitudes towards engaging in sexting (r = .423; p = .001), impulsivity (r = .185; p = .001), age (r = .234; p = .001) and having a steady relationship with a partner (r = .171, p = .001).

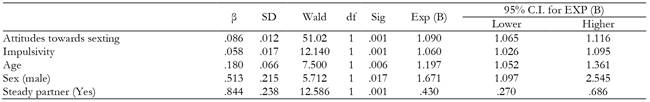

Predictive power of the explanatory variables of sexting behaviour

Lastly, we performed a logistic regression analysis using the forward method, with the variables that have shown significant differences in the analyses that were performed previously. The dependent variable in the study is engaging in sexting. The values of Cox and Snell’s R2 and Naglekerke’s R2 show that the proposed model explains between 20.2% and 29.8% of the variance. As can be seen in Table 5, positive attitudes towards sexting, impulsivity, age, being male and having a steady relationship with a partner are predictive variables of engaging in sexting. The Hosmer and Lemeshow test did not yield statistical significance (X 2 = 5.987; p = .649), which indicates the goodness of fit of the model. In general, good classification results are obtained, with a mean of 79.5% correct classifications. Results are better for sensitivity, as 93% are correctly classified in the group that does not engage in sexting and are somewhat lower as regards specificity, as 39.8% of the teenagers who do engage in sexting are correctly classified.

Discussion

The aim of this work was to estimate the figures for the prevalence of engaging in sexting and to analyse which variables distinguish between people who practice cybersex and those who do not practice it. Conducting this type of study is important for two reasons: because it is a recent phenomenon, little research has been conducted to study its magnitude and the factors involved in it in depth (Chalfen, 2009) and there is a growing need to know what variables should be introduced in the preparation and implementation of preventive strategies (INTECO, 2011).

The prevalence of sending and receiving sexual material in our study (30.5% among males and 19.9% among females) is consistent with the data obtained in a number of international studies (Ricketts, Maloney, Marcum & Higging, 2015; Strassberg, Cann, & Velarde, 2017), where the figures obtained for prevalence range between 20% and 40.5%. In Spain, Alfaro and colleagues (2015) determined an overall prevalence of sexting of 30.3% among boys and 14.6% among girls. However, Gámez-Guadix and colleagues (2017) report lower percentages that range between 2.1% and 7.1% for sending videos and photos, respectively. This inconsistency in the results may be due to a lack of agreement on the definition of sexting (Barrense-Dias, Berchtold, Surís & Akre, 2017), to whether a distinction was made between reports of sending behaviour and receiving behaviour (Fleschler-Peskin et al., 2013) and to the age range of the sample used (Mitchell et al., 2012). Specifically, the high prevalence found in our study with respect to the Spanish study by Gámez-Guadix and colleagues (2017) may be due to our joint evaluation of the rates of sending or receiving sexual contents. These results may be related to the higher expansion of electronic devices in the Spanish society. In fact, some studies focused on habits of ICT among children and adolescents report 2 out 3, between 10 and 16 years old (64.7%), have their own smartphone (INTECO, 2011).

The main motives reported for sexting are wanting to increase the degree of intimacy with one's partner and receiving an express request from the other partner in the relationship. With regard to the first motive, it seems that sexting with the intention of generating trust and intimacy is a motivation that is repeated across different studies (Drouin & Landgraff, 2012). In this regard, Parker, Blackburn, Perry and Hawkes (2013) determined that the main motivations underlying sexting are hedonism (45%) and intimacy (42%). As regards the second motive, i.e. explicit requests or pressure from one's partner, several studies have provided evidence of this reality in young adults (Drouin & Tobin, 2014), which some authors call unwanted but consensual sexting behaviours (Temple & Choi, 2014). Particularly, Temple and colleagues (2012) conclude that 57% of teenagers have sexted because somebody else explicitly asked them to do so. The second motivation would be supported by sexist beliefs of the Spanish social traditions. Therefore, sexting behavior would be influenced by gender roles that attribute to women a submissive role characterised by obedience and compliance with partners’ requests. At the same time, men would maintain a dominant role characterised by the choice of the type of sexual relationship and interaction with their partner (Quesada et al., 2018).

The correlation and regression analyses that were performed confirmed that engagement in sexting is significantly related to some of the psychological and sociodemographic variables analysed, in line with the research conducted by Cooper and colleagues (2016). Teenagers who engage in sexting have a lower capacity to control impulses than those who do not carry out this behaviour. Moreover, impulsivity is established as a significant predictor of initiation and maintenance. These data are in agreement with several studies that determine that engaging in sexting is positively related to the level of impulsivity (Cruz & Soriano, 2014) and negatively related to the level of self-control (Marcum, Higgins & Ricketts, 2014). However, and despite the fact that this behaviour is carried out in an impulsive way, some studies conclude that teenagers are fully aware of the consequences of their actions (Dake et al., 2012; Van Ouytsel et al., 2017). The lack of self-control in risk behavior is coherent with the Dual System model (Steinberg, 2008; Steinberg et al., 2008). In the adolescence, the brain regions responsible for self-control reveal a minor development and, consequently, the emotions underlay behaviors and possible negative consequences are not considered.

Our results, like the other studies that have been analysed, determine a direct relationship between positive attitude and engaging in sexting, so that teenagers with more positive attitudes are the ones who engage in sexting more often (Hudson & Fetro, 2015; Rodríguez-Castro et al., 2017). Like impulsivity, this variable is also a significant predictor of the initiation and maintenance of this behaviour. A review of the main studies on sexting concludes that teenagers who sext have more positive attitudes towards this behaviour and no evidence was detected to show that this practice leads to negative attitudes towards it (Klettke, Hallfor & Mellor, 2014). Furthermore, a study conducted with teenagers between 14 and 17 years of age from different European countries concludes that over half of the adolescents who send sexual images experience positive feelings after the behaviour, such as feeling that they are loved or feeling good about themselves (Wood, Barter, Stanley, Aghtaie & Larkins, 2015). As regards sex, in line with our results, most research shows that boys have more positive attitudes towards sexting than girls. One study conducted with Belgian teenagers found that girls are less willing to sext than boys (Walrave et al., 2015).

One of the predictive variables of engaging in sexting is age, as older teenagers sext more than younger ones. This claim is consistent with a number of studies that have shown the existence of a positive correlation between age and engagement in sexting (Mitchell et al., 2012). Indeed, the study conducted by Dake and colleagues (2012) reports that the age bracket with the highest prevalence is that between 16 and 18 years. At 12 years of age only 3% of teenagers sext, whereas at 18 this figure increases significantly to 32%. These results could be accounted for by the fact that older teenagers have greater access to a mobile phone or to social networks (INTECO, 2011), as well as a higher interest towards sex and the need of stablishing affective and erotic relations. The cyber-interaction provides this need of relation rapidly by information and communication technologies.

With regard to the influence of sex, our results run in the same line as those studies that conclude that boys are more likely to sext (Strassberg et al., 2013) and to seek more sexual sensations (Ballester-Arnal, Ruiz-Palomino, Espada-Sánchez, Morell-Mengual, & Gil-Llario, 2018). These differences may be related to the gender roles prevailing in the society and to the myths of romantic love (Yépez-Tito, Ferragut, & Blanca, 2019). A more sexist society may instigate men to send or own large amounts of sexual content, thus reinforcing their masculinity (Ringrose, & Harvey, 2015); on the other hand, women who perform these same behaviors are penalized to the extent that they are classified as too interested in sex (Livingstone, & Görzig 2014; Ringrose, & Harvey, 2015). Conversely, other studies determine that engagement in sexting is not influenced by sex (Dake et al., 2012; Gámez-Guadix et al., 2017). An explanation for this lack of consensus might be found in the study by Baumgartner, Sumter, Peter, Velkenburg and Livingstone (2014), carried out in different European countries including Spain, which concludes that sex differences vary according to the country and are due to prevailing values and culture, where gender stereotypes related to men and women determine, most of the times, their sexual behavior.

Finally, being in a relationship with a partner is proposed as a significant predictor of engaging in sexting. Consistent with this, Van Ouytsel and colleagues (2017) determine that most of the sexual material that is produced or sent is addressed to a sexual partner. This can be explained by three main motives: trusting that the partner will never disclose the content to other people (INTECO, 2011), establishing flirting as foreplay prior to a sexual relationship, and generating a climate of trust and intimacy (Temple & Choi, 2014).

These findings should be considered in light of some limitations. Firstly, the self-informed questionnaires may facilitate social desirability and bias in adolescents’ response. However, scientific literature has regularly used these type of instruments. In addition, this study has guarantee confidentiality and anonymity of participants. The second limitation is based on the transverse design, in case future studies include longitudinal designs could analyze whether sexting is an unusual or long-lasting behavior.

In conclusion, our results indicate that sending and receiving, texts, photos and videos of a sexual nature, produced by the sender him or herself, is a common practice among Spanish teenagers. This high prevalence emphasises the need of setting up policies to deal with this phenomenon in preventive and educative term, emphasizing information on sexuality (sex education). Given the scant existence of research that performs an in-depth analysis of the explanatory variables of the initiation and maintenance of sexting behaviour, the main contribution of our study is that it increases scientific knowledge about those variables who distinguish between those adolescents that, at least once, have practiced sexting and those who have not done. In this sense, the level of impulsivity, attitudes towards sexting, age and being in a stable relationship are mainly related to sexting practice and, consequently, may be included in designing and developing sexual educative programs.