Introduction

Schema Therapy (ST) is a recent integrative approach sharing different elements with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Gestalt Therapy, Object Relations Theory, Attachment Theory and Transactional Analysis (Young, Klosko, & Weishaar, 2003).

The concept of early maladaptive schemas (EMS) is the core of ST. Young and colleagues defined EMSs as “extremely stable and enduring themes, comprised of memories, emotions, cognitions, and bodily sensations regarding oneself and one’s relationship with others that develop during childhood and are elaborated on throughout the individual’s lifetime, and that are dysfunctional to a significant degree” (Young et al. 2003). According to the ST model, psychiatric disorders result from the development, in childhood, of EMSs in response to unmet emotional needs. In recent years, many studies have shown that EMSs are involved in many psychiatric diseases such as personality disorders (Sempértegui, Karreman, Arntz, & Bekker, 2013), affective disorders (Davoodi et al., 2018; Hawke, Provencher, & Arntz, 2011), obsessive-compulsive disorder (Basile, Tenore, Luppino, Mancini, & Basile, 2017; Voderholzer et al., 2014), social phobia (Calvete et al. 2013; Pinto-Gouveia et al. 2006), eating disorders (Pugh, 2015), substance abuse (Shorey, Anderson, & Stuart, 2013), and psychosis (Stowkowy et al., 2016).

The Young Schema Questionnaire (YSQ; Young & Brown, 1990) is a self-report measure developed to assess EMSs and consists of a long form (YSQ-L) and a short form (YSQ-S). The YSQ-S is made up of 90 items, representing the 18 EMSs defined by the authors, and it was created for research aims due to its faster administration than the long version (Young et al. 2003). In Young’s (2003) theory, EMSs are organized into five domains: disconnection/rejection, impaired limits, overvigilance/inhibition, impaired autonomy/performance and other-directedness, but more recently Bach and colleagues (2018) have found a better fit in a model with four domains: disconnection & rejection, impaired autonomy & performance, excessive responsibility & standards, and impaired limits.

Currently, the YSQ is in its third version (YSQ-S3) (Young, 2005), but to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that aims to validate the Italian version of YSQ-S3 according to the new proposed organization of EMSs into four domains (Bach, Lockwood, & Young, 2018).

Therefore, the purpose of this study is to examine the factor structure of the YSQ-S3 in a non-clinical Italian population by means of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and also to explore the internal consistency, test-retest reliability and concurrent validity of the YSQ-S3, using measures of depression and anxiety for concurrent validity assessment.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Students at the School of Medicine, Nursing Sciences and Sociology from the University “Magna Graecia” of Catanzaro (Italy), and seniors from 14 high schools from 6 different cities in Calabria (Southern Italy) were given the opportunity to participate to the study. The aim of the research was described on the Facebook page of the Ambulatory for Clinical Research and Treatment of Eating Disorders of Catanzaro (Italy). Through an anonymous online survey, the participants completed an informed consent form and the questionnaires. Anonymity was guaranteed using a nickname (formed by at least 8 alphanumeric and symbols characters) that participants used both in the first (test) and in the second administration (retest) of the tests.

The final sample consisted of 1372 participants (N=846; 61.7% women) with mean age 19.45 ± 2.7 years old; 929 (67.7%) participants had middle school diploma while 443 (32.3%) had high school diploma. No differences were evident between males and females (respectively 19.3 ± 2.8 and 19.5 ± 2.5; t= 1.592; p= .112). All participants were Caucasian.

The retest was made available to participants three weeks later for a week; overall, 892 (65%) participants completed a retest after 24.4±3.5 days.

The research was conducted from March 2017 to May 2018.

Instruments

Young Schema Questionnaire S3 (YSQ-S3)

The authors made a double Italian/English forward/backward translation of the YSQ-S3 as follows: once an initial agreement was reached among translators from English to Italian, another researcher, blind to this original version, made the translation back into English. After verifying the similarity with the original test, the YSQ-S3 was given to a small group of 20 volunteers who evaluated the comprehensibility of the items. All raters considered it to be clear and easy to rate.

The YSQ-S3 is made up of 90 Likert type items ranging from 1 (completely untrue for me) to 6 (describes me perfectly) written to assess the presence of the 18 EMSs (Appendix 1).

Beck Depressive Inventory (BDI)

Depressive symptoms were measured using the Italian version of the BDI (Ghisi et al. 2006), which consists of 21 multiple-choice items, rated from 0 to 3. Scores between 0-9, 10-16, 17-29 and ≥ 30 respectively indicate minimum, mild, moderate and severe depression. Cronbach’s alpha in the present research was .886.

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)

The Italian version is made up of 40 items and assesses state (STAI-St) and trait (STAI-Tr) anxiety (Pedrabissi and Santinello 1989). In this study, we examined only STAI-Tr and the Cronbach’s alpha was .934.

Data analyses

Different CFAs were conducted using M-plus (Muthén and Muthén 1998-2015) to examine the best latent structure of the YSQ-S3, including both first- and second-order structures. Firstly, we examined a correlated first-order 18-factor structure, corresponding to the 18 hypothetical EMSs; secondly, we tested a second-order 5-factor structure corresponding to the five domains proposed by Young et al. (2003); finally, we tested a second-order 4-factor structure corresponding to the new organization of EMSs into four domains proposed by Bach et al. (2003).

The weighted least square mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) method was used to estimate the parameters, because it provides the best option for modelling categorical or ordered data (Brown, 2006).

The Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), The Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Standardized Root Mean Squared Residual (SRMR) and relative chi-square (χ2/df) were used to assess the goodness of fit of data to a proposed model. For TLI and CFI, values of 0.90 and above were considered adequate, whereas values of 0.95 or above were considered very good; for RMSEA values of 0.08 and below was considered adequate and 0.05 or less very good; for SRMR a cut-off value close to 0.08 was considered adequate. Values of χ2/df <3.0 are good and those <2.0 are very good. The levels of these indices were evaluated according to the recommendations of Hu and Bentler (1999).

The McDonald’s ω reliability coefficient was calculate using JASP open-source software (JASP, Version 0.9.2, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands).

The intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) along with the 95% confidence interval (CI) was run to calculate test-retest reliability. According to Cicchetti's suggestions, we considered that ICC <.40, .40 −.59, .60 − .74, and .75 − 1.00 respectively indicate that the level of clinical significance was poor, fair, good and excellent (Cicchetti, 1994).

Correlations between YSQ-S3 and STAI-Tr and BDI were calculated to measure construct validity, considering that correlation coefficients greater than .30 are recommended (McGraw & Wong, 1996).

A p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Reliably of the scores

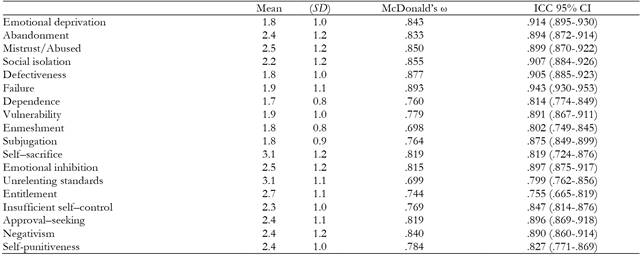

As displayed in Table 1, the McDonald ω coefficient of the 18 EMSs ranged from .698 (Enmeshment) to .893 (Failure), indicating very good reliability.

Regarding test-retest reliability, ICC (95% CI) ranged from .755 (.665-.819) for Entitlement to .943 (.930-.953) for Failure, showing an excellent stability.

Confirmatory factor analysis

The fit indices of the three CFA models tested are shown in Table 2. It is evident that some of the fit indices of these models do not meet the cutoff to define a model as valid (i.e. χ2/df, CFI, TLI). However, the distributions of fit indices are affected by different conditions such as the sample size and the distribution of the data (Yuan, 2005). Therefore, cutoffs of fit indices cannot be considered the only way to evaluate a model's validity. For this reason, low fit indices do not necessarily indicate a poor fit. McNeish et al. (2018) suggested evaluating the validity of factor models not only on goodness of fit indices, but also with factor loadings that represent the quality of measurement of latent variables. In fact, according to the reliability paradox, it can be observed that models with low factor loadings could have better fit indices than model with high factor loadings (Hancock & Mueller, 2011).

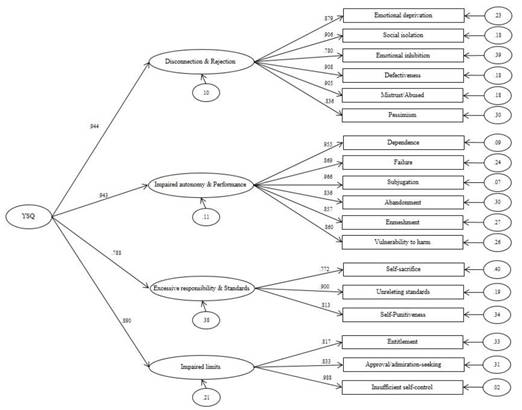

Based on these recommendations, the second-order model with four factors has the highest factor loadings when compared with the other two models (as displayed in figure 1).

Sources of validity evidence of internal structure

As displayed in Table 3, all 18 EMSs were significantly correlated with the BDI (ranging from .143 for Unrelenting standards to .707 for Negativism) and STAI (ranging from .141 for Unrelenting standards to .768 for Negativism).

Discussion

The aim of the present research was to validate the new four-domain model of the YSQ-S3 in a large non-clinical sample. Recently, several studies have investigated the role of each EMS in the psychiatric disorders; for this reason, having a psychometrically valid assessment tool tested in a non-clinical sample is necessary and very useful.

Our results indicate that this version of the YSQ-S3 is a solid tool with good psychometric properties, in particular good reliability and excellent test-rest reliability. Furthermore, the McDonald’s ω of almost all EMSs were higher than 0.7, which indicated good internal reliability. However, Unrelenting Standards and Enmeshment had slightly less than good internal consistency, although they were still within the adequate range. The low reliability coefficients of these two EMSs were similar to previous versions in other languages (Calvete, Orue, & González-Diez, 2013; Hawke & Provencher, 2012; Soygüt, Karaosmanoğlu, & Cakir, 2009), so it seems that our version of YSQ-S3 has good enough reliability to be used without serious revision.

Regarding the CFAs, pre vious validation studies of YSQ-S3 have tested the latent factor structure of the questionnaire and they found mixed results. In fact, some researchers have centered their interest on the first-order factors, namely the 18 EMSs (Hawke & Provencher, 2012; Lee, Choi, Rim, Won, & Lee, 2015), while others have gone further, describing some of the five second-order domains (Calvete et al. 2013; Kriston et al. 2012; Sakulsriprasert et al. 2016). These discrepancies in the factor structures may be for different reasons, such as translation problems, the sample used in the research or cultural differences.

In our study, although some model fit indices were not good, factor loadings appeared robust. In fact, even if the first-order factors model showed the best fit, some loadings of the 90 items did not appear to be significant for the corresponding EMS. Instead, in the second-order model, the factor loadings of all the four domains on their EMSs were significant. Therefore, this last model was chosen, as it showed more adequate measurement properties than the other two models.

Regarding concurrent validity, each schema of the YSQ-S3 was highly correlated with BDI and STAI-Tr scores, and this result is consistent with the versions of the YSQ-S3 in other languages (Lee et al. 2015; Soygut et al. 2009). This finding is not surprising; in fact, the EMSs are well known to be implicated in depressive and anxiety symptoms (Davoodi et al. 2018; Rezaei et al. 2016). For this reason, some researchers have proposed that ST should be also applied in the treatment of mood and anxiety disorders (Hawke & Provencher, 2011; Malogiannis et al., 2014).

Our results should be interpreted with caution due to certain limitations. First, in the present study, all data were obtained via online questionnaires. On one hand, this allows for recruitment of a large number of participants, but on the other hand it could lead to a selection or response bias (Mayr et al., 2012). Second, our sample is composed of a large non clinical population, so caution is needed in generalizing our findings. There are various reasons why we feel our choice was justified. First, the validation of a test in a foreign language has the aim to demonstrate that the new version matches with the original one, whose validity has been already demonstrated by the authors of the test. In addition, many studies regarding YSQ-S3 validations in other languages have used sample with student populations (Calvete et al. 2013; Lee et al. 2015; Sakulsriprasert et al. 2016). Nevertheless, we believe that further studies with a clinical sample of Italian patients are necessary to replicate and extend the present results. Finally, our study being based on self-report questionnaires could be subject to some limits as reduced introspective ability of respondents, social desirable answers, response bias or sampling bias. However, self-report scales allow a ‘cheap’ way in terms of both time and cost of obtaining data; furthermore, they can be used to measure constructs that would be difficult to obtain with behavioral or physiological measures.

Despite these limitations, the strength of our research is that this is the first study that tests the new four-domain model recently proposed by the authors (Bach et al. 2018), which has received little attention to date.

Conclusions

Summing up, the Italian version of the YSQ-S3 has demonstrated sound psychometric properties such as good internal consistency and excellent test-retest reliability. In addition, the present study supports the new proposed organization of EMSs into four domains. Thus, this study has shown that the Italian version of YSQ-S3 can be a useful and valid tool for clinicians and researchers in the self-report measurement of EMSs.