Introducción

Spanish organisations have for some years now been starting to design and implement health management and promotion actions. This has led to organisations and their leaders being concerned about the health of their employees and the concept of healthy organisations has emerged. Originally, the concept began as healthy and/or positive institutions, and distinguished between healthy and toxic organisations (Dejoy and Wilson, 2003). The concept has evolved from various authors (Cooper and Cartwright, 1994; Elliot and Macpherson, 2010) to the Healthy and Resilient Organization (HERO) model (Salanova, Llorens, Cifre and Martínez, 2012) which is a theoretical model that is composed of theoretical evidence from research on occupational stress, human resource management, organisational behaviour and from the Psychology of Positive Occupational Health (Llorens, Del Libano, and Salanova, 2009); Salanova, Llorens, Cifre, and Martínez, 2009; Vandenberg, Park, DeJoy, Wilson, and Griffin-Blake, 2002). According to Salanova et al. (2012) it is understood that a healthy and resilient organisation combines three key elements that interact with each other: healthy organisational resources and practices; healthy employees; healthy organisational results (Salanova, 2009; Salanova, Cifre, Llorens, Martínez, and Lorente, 2011; Salanova et al., 2012). In addition, they are defined as organisations that make systematic, planned and proactive efforts to improve employee health through good practices related to task improvement, social environment and organisations (Salanova, 2008; Salanova and Schaufeli, 2009). On the other hand, healthy employees are those who belong to healthy organisations and are characterised by psychological strengths and capabilities that can be measured and managed to achieve improved organisational functioning and performance (Salanova, 2008). At first, the healthy employee was defined as psychological capital (PsyCap) with the characteristics of self-efficacy, hope, optimism and resilience (Luthans and Youssef, 2004; Stanjovik, 2006), to later be called a healthy employee and add the dimension of engagement (Salanova, 2008; Salanova, 2009).

The strengths of the healthy employee have been studied in the work environment, where Xanthopoulou, Bakker, Demerouti and Schaufeli (2009) showed that self-efficacy, mental and emotional competence, self-esteem and optimism are positively related to well-being. Group social resources also completely mediate the relationship between positive group emotions and performance (Peñalver, Salanova, Martínez and Wilmar, 2019). In addition, engagement and self-efficacy are related to greater personal initiative, which implies improved performance (Lisbona, Palací, Salanova and Frese, 2018). On the other hand, psychological capital (Luthans and Youssef, 2004) is related to well-being at work (Avey, Luthans, Smith and Palmer, 2010).

Along the same lines, Hernández, Llorens and Rodriguez (2014) show that beliefs in efficacy and positive effects are positively related to engagement in the health care environment. In the same sense, but in individual concepts, the beliefs of effectiveness are positively related to coping with stress and health in organisations (Salanova, Peiró and Schaufeli, 2002), and engagement (Ventura, Salanova and Llorens, 2015). Employee engagement is related to higher performance (Bakker and Demerouti, 2017; Schneider et al., 2017), greater entrepreneurship and creative ideas (Gawke, Gorgievski and Bakker, 2017; Orth and Volmer, 2017). Optimism is positively related to employees with greater resources to cope with emotional stress and increase self-esteem (Jimenez, Montorio and Izal, 2017). It also minimises the effects of mobbing (Sprigg et al., 2018) and burnout (Gallavan and Newman, 2013), and is a predictor of life satisfaction (Chico and Ferrando, 2008).

The instruments used to measure the strengths of the healthy employee are engagement (Schaufeli and Bakker, 2003), self-efficacy (Parker, 1998), optimism (Scheier and Carver, 1985), resilience (Wagnild and Young, 1993), and hope (Snyder et al, 1996). Each of these scales selected has considerable psychometric support in multiple samples in previous research and has also been verified in workplace studies on their own or in combination (Jensen and Luthans, 2006; Larson and Luthans, 2006; Luthans, Avolio, Walumbwa and Li, 2005; Peterson and Luthans, 2003).

Similarly, HERO (Salanova et al., 2012) proposes in one of its three axes to measure in a single questionnaire the five strengths of the healthy employee. However, the questionnaire has eight dimensions: positive emotions, engagement vigor, engagement absorption, engagement dedication, resilience, self-efficacy, mental competence and emotional competence (Salanova et al., 2012). Thus, the instrument consists of eight dimensions, establishing three dimensions to value engagement, and two dimensions to value hope through competition. This fact makes us consider the reduction of the instrument from eight dimensions to five dimensions since the literature establishes five dimensions for the healthy employee (Salanova, 2008; Salanova, 2009), self-efficacy, hope, optimism, resilience and engagement (Salanova, 2008; Salanova, 2009; Salanova et al., 2012), and thus provides greater comfort and an approach of the instrument to the theoretical concept.

Therefore, this study aims to validate the HERO instrument (Salanova et al., 2012) by reducing the construct of the healthy employee from eight dimensions to five dimensions and to ascertain its reliability as a means of evaluating the healthy employee.

Method

Participants

Three companies were involved in the study, with a total of 287 participants. Company A is in the food industry and has more than 1000 employees distributed in different factories. A sample of 100 is obtained from this firm, which means 34.84% of the total of the sample. Company B is dedicated to consulting and web development, and, among all its locations, currently has about 300 employees, of which 180 work in Seville. The sample collected in this company was 152, 52.96% of the total. Company C, is a Sevillian company that is an integral consultancy in human resources. It contributed 12.20% of the total sample (n = 35). As to the gender of the participants, 72.47% (n = 208) are men and 27.53% (n = 79) are women (Table 1). 30% (n = 30) of the employees in the company A are women, and 70% (n = 70) are men. The female employees of company B account for 23% (n = 35) of the sample, while the men are 77% (n = 117). Finally, in company C, the female employees in the sample are 34.3% (n = 12), while the male employees are 65.7% (n = 23).

The non-probabilistic method of sampling was used as it had access to all three companies and each belonged to a different sector.

The age distribution of the study’s participants is as follows: 30.31% (n = 87) are between 20-29 years old, 42.86% (n = 123) are between 30-39 years old, 19.51% (n = 56) are between 40-49 years old, only 3.83% (n = 11) are between 50-59 years old.

Material

The Healthy and Resilient Organization Questionnaire (HERO).

HERO, in its healthy employee questionnaire, confirms its psychometric properties, and Cronbach's α coefficient supports the internal validity and reliability of the instruments with employees (Salanova et al., 2012). The instrument consists of 40 items structured with the first scale of optimism measured in the healthy employee questionnaire by the concept of positive emotions, these being measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale consisting of six items. The second scale, engagement is structured in three dimensions, engagement vigor (1), which is measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale, where 0 is never and 7 is always, consisting of seven items. A second dimension of engagement dedication (2) is measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale, where 0 is never and 7 is always, consisting of four items. And the third dimension engagement absorption (3) is measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale, where 0 is never and 7 is always, consisting of seven items. The third scale, resilience, is measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale, where 0 is never and 7 is always, consisting of seven items. The fourth scale, self-efficacy, is measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale, where 0 is incapable of doing it and 7 is sure of doing it well, consisting of three items. And, finally, the fifth scale of hope is measured in the healthy employee questionnaire by two dimensions, mental competence (1), which is measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale , where 0 is never and 7 is always, consisting of three items; and emotional competence (2), which is measured on a 7-point Likert-type scale , where 0 is never and 7 is always, consisting of three items.

Procedure

The procedure for contacting the companies was the following. Firstly, an email containing a letter of introduction and explaining the research project Secondly, if the company responded with concerns, a more elaborate document was sent having a link to the Google forms for the company manager or head of human resources to send to their employees. The employees answered anonymously and voluntarily. The period for collecting information from participants began in May 2015 and ended in May 2016. The final matrix was obtained in September 2016. The informed consent of the participants was subsequently obtained. Authorisation was also obtained from the Ethics Committee of the University of Málaga (No. 243, CEUMA Registry No.: 19-2015-H). The principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, 2013), which sets out the fundamental ethical principles for research involving human subjects, were also met.

Later, the fit of the five- and eight-dimensional models was analysed by Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), using the Robust Maximum Likelihood estimation method (Satorra and Bentler, 2001) implemented in the Lisrel 8.80 program (Jöreskog and Sörbom, 2006), given the ordinal scaling of all the indicators.

Statistical analysis

The statistical programmes used have been SPSS (22.0), SAS v.9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., 1999; Schlotzhauer & Littell, 1997), LISREL 8.8 (Jöreskog and Sörbom, 2006) to perform Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and SAGT (Hernández-Mendo, Blanco-Villaseñor, Pastrana, Morales-Sánchez and Ramos-Pérez, 2016) to perform generalisability analysis.

First, an analysis of the variance components was performed using a leastsquares procedure (VARCOM Type I) and a maximum likelihood procedure (GLM).

The following are the psychometric properties of the healthy employee construct. For this purpose, the fit of the 5- and 8-dimensional models was analysed by means of an AFC, using the method of Maximum Robust Likelihood estimation (Satorra and Bentler, 2001) implemented in the Lisrel 8.80 programme (Jöreskog and Sörbom, 2006), given the ordinal scaling of all the indicators. According to the fitting criteria of Hu and Bentler (1995), each model was assessed using the relative scaled Chi Square of Satorra-Bentler (SB - X2 / GL), CFI (Comparative Fit Index), NNFI (Non-Normed Fit Index of Bentler and Bonett), SRMR (Standardised Root Mean Square Residual) and RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation). Based on Hu and Bentler (1999) and Byrne (2010), χ2 / gl ≤ 3, CFI and NNFI ≥ .90, SRMR and RMSEA ≤ .08 are considered to reflect an appropriate adjustment. In addition, an adjustment was made to the five- and eight-dimensional models, showing the incremental indices (CFI and NNFI) and the absolute SRMR.

The differences between the Chi Square contrast statistics of each of them and between their degrees of freedom were also calculated, associating a value of "p", meaning each of the discrepancies found. In addition, the difference between their respective CFIs was calculated.

And, finally, after verifying that a reduction in the number of factors did not significantly worsen the adjustment, the five-dimensional model was analysed in terms of convergent, discriminant and composite reliability. Also, descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, asymmetry and kurtosis) and factor loads are shown.

Results

Through the analysis of variance components, a 9-faceted model [y=p e c u s d n a m ] was used, where: Participant (p) x Company (e) x Center (c) x Position (u) x Sex (s) x Department (d) x Nationality (n) x Age (a) x T.Company (m). Due to the saturation produced by working with such a high number of facets, the model [y=p e c u s d n a m ] was initially used without interactions. It was obtained that the error variance with both procedures is the same (GLM=11152 / VARCOMP=11152), the model and the facet [p] are significant (<.0001), explaining 98.6% of the variance. The rest of the facets collapsed because of the contribution to the model of the facet [p]. Another analysis without interaction with the model [y=e c u s d n a m ] is carried out to find out the contribution of each facet, dispensing with the facet [p]. The model and all the facets are significant, explaining 98.19% of the variance. The error variance with both procedures is the same (GLM=11399 / VARCOMP=11393). From this analysis, the 4 facets that contribute the most variance to the model are considered, and a new analysis is carried out, with all the interactions, with the model [y=e|c|u|s ]. The model and all the facets with their interactions are significant (except for the e*c*s and e*c*u*s interactions). The model explains 98.27% of the variance. The error variance with both procedures is the same (GLM= 11375 / VARCOMP= 11375). With these estimated results on the equality in the variance error, both a minimum squares procedure and maximum likelihood, it can be assumed that the sample is linear, normal and homoscedastic (Hemmerle & Hartley, 1973; Searle, Casella & McCulloch, 1992).

When a generalisability analysis is performed with a cross-faceted design on the model [c] [u] [s] / [e], generalisability coefficients higher than .99 are obtained (relative G=.996 and absolute G=.995). This data confirms the capacity of generalisation of the numerical structure of the sample studied.

Confirmatory factorial analysis

Evaluating the fit of a model is a relative process rather than one based on absolute criteria, so it is more appropriate to jointly evaluate various types of measures to assess the acceptability of a model (Morales-Sánchez, Hernández-Mendo and Blanco, 2009). Furthermore, with relatively large samples, the contrast power is high and can lead to a rejection of models due to insignificant specification errors or discrepancies (Bentler and Bonnet, 1980; Bollen, 1990). A comparison between the two models was carried out in order to determine the one with the best fit of the empirical data. The difference between the Satorra-Bentler scaled Chi-Square values and the degrees of freedom of both models were examined in order to compare them in terms of fit. However, given the sensitivity of Chi Square to sample size, the criteria of Cheung and Rensvold (2002) were also followed, so the difference between the values of the Bentler Comparative Index (BCI) was calculated, rejecting the model with the lowest BCI when the discrepancies were greater than 0.01. Discrimination between factors was also considered as a selection criterion in multidimensional models. According to Lévy and Varela (2003), constructs with correlations between their indicators above 0.85 should be merged into a single factor, while correlations between constructs below 0.5 will show that such indicators belong to different latent variables. Finally, using the SPSS 23.0 statistical package, the internal consistency of the scales of the model finally selected was evaluated using Cronbach's Alpha coefficient, assessing its suitability (α ≥ .70) according to George and Mallery (1995). Indicators whose corrected item-total correlation was less than .35 and/or negative or whose exclusion caused an increase in the Alpha coefficient (Muñiz, Fidalgo, García Cueto, Martínez and Moreno, 2005) were not considered suitable (Nunnally and Bernstein, 1995).

Adjustment of the five and eight dimensional models

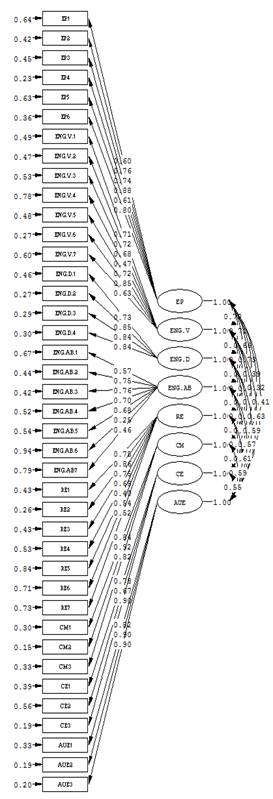

For the target analysis, the two models of the healthy employee were compared. A first model had eight dimensions: positive emotions which was identified by 6 indicators, engagement vigor, engagement absorption and resilience by 7, engagement dedication by 4, mental, emotional competence and self-efficacy by 3 (Figure 1). The second model reduced the previous dimensions to five, as engagement was considered a single dimension with 18 indicators after grouping vigour, dedication and absorption, and competence was another dimension with 6 indicators that brought together the mental and emotional components (Figure 2).

Table 3 shows the setting for both models. The incremental indices (IFC and NNFI) and the absolute SRMR showed a good fit in both models, being higher than .90 and lower than .08, respectively. In contrast, the other indices pointed to a mediocre, although not unacceptable, adjustment, as the RMSEA did not exceed the .10 criterion (Arias-Martínez, 2008), and Satorra-Bentler’s relative Chi Square was below 5 (Hu and Bentler, 1999).

Comparison of the fit of five- and eight-dimensional models

Table 4 shows the comparison of the fit of the five- and eight-dimensional models. These results showed a significant increase in the Satorra-Bentler Chi-Square contrast statistic in the five versus the eight-dimensional model, although the reduction of the CFI in the five-dimensional model did not exceed the .01 criterion, allowing both models to be considered as similar in terms of fit.

Convergent, discriminant validity and reliability of the five-dimensional model

Regarding convergent validity (Table 4), the dimensions positive emotions, competence and self-efficacy all showed significant factor loads according to Wald's test (p < .001). In addition, the average of these was above 0.7 in all the dimensions, and only the standardised coefficient of item CE2 (Be aware and remember many things at once) was below .6. Although all the standardised loads of the remaining two factors were statistically significant, the average of them did not reach the criterion of .7. It was highlighted that, in the engagement dimension, five loads (28%) were lower than .6, with item ENGA6 (It is difficult to disconnect from the task) being too low in relation to the rest. In "resilience", three loads (43%) were lower than .6, the lowest being item RE5 (We think that the company has sufficient economic solvency to overcome difficult times).

As for the composite reliability (Table 5), the items that defined each of the dimensions of the model showed good internal consistency, obtaining values higher than .8 in all the cases. In addition, Table 5 shows the descriptive statistics (Mean, standard deviation, asymmetry and kurtosis) and the factorial loads.

With regard to discriminant validity (Table 6), the correlations between pairs of dimensions were squared to obtain the shared variance between them in order to compare them with the extracted variance obtained in each of them. The positive emotions, competence and self-efficacy dimensions clearly surpassed the criterion of discriminant validity, since the high value of their standardised factor loads meant that their average variance extracted were higher than the variances which they shared with the rest of the dimensions. On the other hand, contradictory results were obtained in the two remaining dimensions, because the average variance extracted from engagement was lower than the variance shared with positive emotions and resilience, while the variance in the latter dimension was lower than the variance shared with positive emotions and engagement.

Table 5. Descriptive item analysis, standardised factor loads, composite reliability of the five-dimensional model, asymmetry and kurtosis.

Discussion and conclusions

The concept of the healthy employee is eminently alive. In fact, in their study Salanova et al. (2014) determine the healthy employee with positive emotions, engagement, resilience, optimism and self-efficacy beliefs, being able to observe that the concept of hope is not included. One year later, works were published in which it was emphasised that the HERO model tests specific relationships between some variables so that in this study the healthy employee is determined with: efficiency, engagement, confidence, resilience and positive affections (Acosta, Cruz-Ortiz, Salanova and Llorens, 2015; Salanova et al, 2016), and, as can be seen again, there is a change in the concepts that define the healthy employee maintaining resilience and engagement, and modifying self-efficacy for effectiveness, positive emotions for positive affections and trust enters as a new element. On the other hand, Olvera, Llorens, Acosta and Salanova (2017) introduce the concept of organisational trust, and add to the concept of the healthy employee that of healthy work groups (Pelaez, Salanova and Martínez, 2017). Finally, Salanova et al. (2019) define the healthy employee with seven dimensions, the beliefs of efficiency, engagement, optimism, satisfaction, confidence, positive emotions and resilience.

The evolution that is taking place in the concept of the healthy employee through the WANT research team is, as mentioned before, remarkably alive and the construct can be modified according to the evolution of organisations, society, culture, economy. An important finding is the increase of the PsyCap concept from four dimensions, optimism, resilience, self-efficacy and hope (Luthans and Youssef, 2004; Stanjovik, 2006), to five including engagement (Salanova, 2008). There are instruments that measure this, and in the case of the healthy employee construct a single instrument measures all the five dimensions. In view of the above, the five-dimensional construct is more suited to the scientific literature than the eight-dimensional one, so researchers have an instrument with the reduced but adequate dimensions.

With respect to the AFC results, it can be stated that the incremental indices (CFI and NNFI) and the absolute SRMR showed a good fit in both models, being higher than .90 and lower than .08 respectively. Also satisfactory is the fact that the five-dimensional versus the eight-dimensional construct of the healthy employee can be considered, showing that both models are similar in fit, as the five-dimensional model did not exceed the .01 criterion in the CFI reduction.

Discriminant validity indices of the "positive emotions", "competence" and "self-efficacy" scales were optimal; that is, the mean variance extracted from each latent variable was greater than the square of the correlation between them (Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson and Tatham, 2006), but contradictory results were found in the "resilience" and "engagement" scales.

As for the mean variance extracted, which is a complementary measure of composite reliability, the scales "positive emotions", "competence" and "self-efficacy" had p > .50, while "engagement" and "resilience" had p > .40. This implies that a mean percentage of the variance is explained by the construct compared to the variance of the measurement error. In the same way as the composite reliability, the joint reliability of the indicators of a latent variable has been found to be higher than .8 in all the cases. These results are in line with those estimated by Morales-Sánchez, Hernández-Mendo and Blanco (2009).

Limitations and future research lines

The use of the instrument carried out mainly by the WANT group makes it a limitation for this study, since we cannot contrast the use of the instrument by other researchers, the results and opinions about it.

On the other hand, research should be directed towards the use of the instrument in different sectors, such as food, computers, education, sport, etc., and in turn the dimensions of the healthy employee established.

Future research lines must be focused on proposing the definitive model of the healthy employee with its established dimensions, adding to the five dimensions of trust, satisfaction, and any other that researchers consider, according to the evolution of the organisations and the employees themselves.

texto en

texto en