Introduction

Gender-based intimate partner violence (IPV) is a human rights and public health problem that affects a third of women in the world (Ellsberg et al., 2008; World Health Organization, 2013). Approximately 275 million children and adolescents are exposed to IPV worldwide (United Nations International Children's Emergency Fund (UNICEF), 2006), and for children under 5 years of age, it is estimated that 1 in 4 children live with a mother who is a victim of IPV (UNICEF, 2017). In Chile, various surveys show that between 12.6% (Subsecretaría de Prevención del Delito, (SPD), 2017) and 29.8% (SPD, 2013) of children and adolescents acknowledge the occurrence of IPV in their home.

Several international systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown that exposure to IPV during childhood and adolescence is related to greater internalized and externalized problems (Evans et al., 2008; Holt et al., 2008; Wolfe et al., 2003), trauma symptoms (Evans et al., 2008) and negative effects in social functioning, physical health and cognitive abilities (Howell et al., 2016). It has also been reported that exposure to IPV can increase the risk of suffering physical, emotional and sexual abuse (Bidarra et al., 2015; Holt et al., 2008). In this field of study, multiple authors emphasize the relevance of investigating the effects associated with IPV while considering children's development (Holt et al., 2008; Wolfe et al., 2003). Developmental psychopathology provides a theoretical framework that could contribute to furthering the understanding of the heterogeneity and complexity of the effects associated with growing up in a home with IPV (Miranda et al., 2011). This framework argues the need for a multidimensional approach to understand that children's development could be determined by constant dynamic interactions between the individual and the environment (for example, the family and social context) (Sameroff, 2009) and the impact of violence could be determined by various factors; therefore, there is rarely a direct causal path that leads to a specific effect (Wolfe et al., 2003). Consequently, there is evidence on some of the mechanisms through which IPV can negatively affect child mental health, such as physical punishment (Miranda et al., 2011), harsh parenting (Grasso et al., 2017), negative life events (Miranda et al., 2013a), and the mother's psychopathology (Miranda et al, 2013a, 2013b).

Most of the studies on child and adolescent IPV exposure and mental health problems are based on reports from mothers and use quantitative methodology, which is why many researchers currently emphasize the importance and need to delve directly into children's and adolescents' experiences related to growing up in an environment with IPV in order to understand -from their own experiences- the impact associated with this type of violence (Callaghan et al., 2015; DeBoard-Lucas & Grych, 2011; Øverlien, 2010).

Historically, there has been a change in the understanding of and the concept used to account for the experiences of children and adolescents who grow up in homes with IPV. Early investigations described them as "witnesses or observers" (McIntosh, 2003). Decades later, research showed the negative impact of IPV on children and adolescents, which caused a change in the understanding of the phenomenon also involving the position of children and adolescents, reason for which they adopted the term “exposure to IPV” (Evans et al., 2008). Recently, from the qualitative approach, the terms “experience of IPV” (Øverlien, 2010) or “children and adolescents who experience IPV” (Callaghan et al., 2015) have been proposed, since these concepts consider the different ways in which children and adolescents experience this type of violence, regarding them as “active agents” within the dynamics of IPV (Edleson, 1999; Holden, 2003; Øverlien, 2010).

Various studies have observed that IPV may be associated with an impact on children's and adolescents' emotional functioning, observing greater emotional incompetence and dysregulation (Callaghan et al., 2017). This suggests that children and adolescents receive little emotional support from their parents, hindering their proper learning about their own emotions (Katz, 2016). This emotional dysregulation could be associated with social difficulties, negative interactions between peers, externalization and internalization of problems (Callaghan, et al., 2017), and aggressive behaviors toward siblings, peers, parents or authority figures (Howell et al., 2016). Furthermore, it could influence the future development of violent relationships, considering the intergenerational transmission of violence as a key factor (Holt et al., 2008).

Studies that have explored children's perspectives reveal that the impact of IPV can be understood from their views of the mother figure, some having difficulties in providing coherent descriptions of their mothers, and even having traumatic reactions when reflecting on the caregiver figure (Pernebo & Almqvist, 2017). There are also reports of children developing distorted beliefs about their caregivers or fathers-aggressors, establishing ambivalent relationships with them and even minimizing the acts of violence that they have exercised against their mothers (Cater & Sjogren, 2016). Therefore, it is relevant to consider how children and adolescents who have grown up in homes with IPV develop patterns of interaction, beliefs, and attitudes about interpersonal relationships (Howell et al., 2016).

Most of the above studies come from European countries and the United States, and there is currently little knowledge from Latin-American countries on this phenomenon (Miranda and Corovic, 2019). This research aims to generate knowledge regarding the impact that IPV can have on children, trying to understand -from their perspectives- what consequences to their emotional functioning occur and how these consequences manifest in their person. Consequently, the objective of this study is to understand the psychological impact associated with growing up in homes with IPV, from the perspective of children.

Methods

This study is part of a larger research project -pioneering in Chile and Latin America- led by the first author, which focuses on the experiences and effects of IPV in children and adolescents.

Participants

The participants were 8 children (3 boys and 5 girls), between 8 and 12 years old, users of the Center for Child and Youth Protection program in the city of Santiago, Chile. They were intentionally selected from the aforementioned project, following inclusion and exclusion criteria based on international recommendations on research ethics with children and adolescents that have grown up around IPV (Morris et al., 2012). The participant inclusion criteria were: 1) having been exposed to IPV during the last year; 2) being between 8 and 17 years old (this study only incorporated participants up to 12 years old); 3) being in the diagnostic phase of the Child and Youth Protection program; and, 4) currently living with their mother and having lived with her for at least 6 months in the previous year. This last criterion sought to ensure that each participant had a stable support figure during their participation in the research (Morris et al., 2012).

Conversely, the participant exclusion criteria were: a) children and their mothers with protected name and address; b) children and their mothers with court orders evidencing that they continue to live in a very difficult situation (this criterion was evaluated on a per case basis, jointly by the research team and the professionals of the program in charge of each participant); c) child not currently living with their mother.

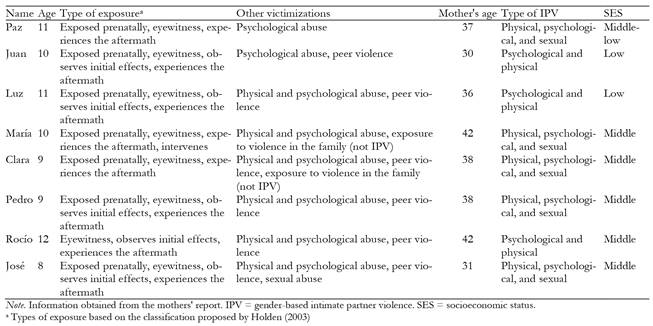

The characteristics of the participants provided by the mothers are presented in Table 1. In general, most of the participants experienced different types of IPV at home from a very early stage, as well as experiencing other forms of intra- and extra-family victimization.

Data generation and collection techniques

We used a semi-structured interview based on Callaghan et al (2015) that was linguistically adapted to the Chilean population. This interview was chosen because it allows exploring the experiences of violence, impact on and coping strategies of children who have grown up in homes with IPV. The adaptation was carried out by the research team and the final script included a question on the perception that children and adolescents have of their parental figures. The interview script included 13 questions overall, with a format that allows space and freedom to be answered openly or freely by the interviewees (Canales, 2006). Appendix 1 presents the interview script.

Procedure

To select the participants, the Child and Youth Protection program professionals referred cases that met the inclusion criteria to the research team. The team members contacted the mother by phone to tell her about the project, inquire whether she wished to collaborate and ask her to talk to her child to see if they would like to participate in the investigation. Then, the research team requested the informed consent of the mother and then the informed assent of the child. Later, the program's professionals carried out the semi-structured interviews with the children. Each participant was interviewed once, with an average interview time of 21 minutes (range: 9-44 minutes). The research team returned the main findings of the investigation to the same program professionals.

Interview analysis

We used thematic narrative analysis (Riessman, 2008) to analyze the interviews. This analysis uses narratives as the unit of analysis, considering them both a method and phenomenon of study (Pinnegar & Daynes, 2007). This is because they are constructed as accounts or stories of a series of events, with the participant's perspective and their construction of meanings being essential elements (Pinnegar & Daynes, 2007). The interviews were audio recorded, transcribed and later analyzed by members of the research team using the ATLAS.ti software (version 7.5.4) through coding and triangulation sessions where the results were contrasted and discussed. First, an intra-case analysis was performed, analyzing each interview separately. Then an inter-case analysis was carried out, visualizing common and differential aspects among the interviews, which were integrated and organized into themes and sub-themes. The triangulation process, as well as the conceptual analysis and interpretation work, followed the criteria of rigor and quality in qualitative research (Morse et al., 2002). We used the saturation criterion proposed by Mayan (2009), which is fulfilled when the findings can show something novel and important about the phenomenon under study; in this case, the impact on growing up in the context of IPV.

Ethical considerations

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Social Sciences of the University of Chile. Considering the sensitivity and complexity involved in including children who have experienced situations of violence in investigations, various measures were taken to protect their rights: 1) specialized training was given to the program professionals on IPV and the investigation's instruments and procedures; 2) an evaluation and support protocol was designed for use in the event of an adverse emotional reaction by children and adolescents during the interview; 3) a risk assessment was carried out according to the exclusion criteria, to ensure that children in a high-risk situation did not participate in the study (Morris et al., 2012); 4) the members of the research team obtained written consent from the mothers and assent from the participants to avoid any coercion to participate from the program professionals. During the analysis, the names of the participants were changed to protect their anonymity. In this research, all the children who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were sequentially included, until reaching the abovementioned saturation criterion (Mayan, 2009). There were no cases excluded for being at high risk.

Results

The results obtained from the narrative analysis were organized into themes and subthemes. The first theme is called “IPV experiences” and includes the description of the general aspects of the narratives on this experience, the recognition of IPV, and the child's assessment of this experience. The second aspect concerns IPV's individual impact on children, describing two subthemes: their self-concept, and the emotional impact of this experience on them. The third theme refers to the impact of IPV on children's relational contexts, which describe their relationships with their father's family, their mother's family, and their mother, father, siblings, and peers. Lastly, the fourth theme concerns other forms of victimization.

IPV experiences

Recognition of IPV. All but one participant acknowledged having grown up in an IPV environment. The exception was a girl who didn't explicitly refer to IPV in her home. When acknowledging experiences of IPV, three participants immediately made a brief description of some of the incidents they were involved, related to direct experiences where they heard and saw acts of violence by their fathers toward their mothers.

I don't like them fighting… my dad and with mom (Do you think you have grown up in that kind of situation?) Hmmm yes… because my parents used to fight a lot. (Juan, 10 years old)

Description of IPV. All the participants who described episodes of IPV described the violence being perpetrated by their father toward their mother. Most of them offered extensive and detailed descriptions focused on a particular event. They described events of physical and psychological violence that they observed and heard, such as screams, arguments, insults, destruction of household items, blows, evident marks on their mothers (such as bruises) and emergency assistance, usually police or firefighters. One of the youngest participants gave a detailed description of the level of violence that he lived at home.

My dad broke two doors in my house… when he closed the door, my dad kicked (the door) really hard and the door fell off and he almost hit my mom in the eye! … She called the police. (Pedro, 9 years old)

Some of the children began their narratives speaking about themselves as a protagonist, then they described the IPV situation experienced, including in it their personal experiences and what they did in these episodes of violence. In other narratives, the children don't appear as a protagonist, being shorter and sparser descriptions, which could be related to unawareness, negation, affective distancing or acknowledging a single episode of IPV.

(Do you think you have grown up around fights or arguments?) I mean, it's a fight because they get mad, they don't fight every day, it just happened once… They're their fights, I don't really understand. (José, 8 years old)

Assessment of IPV experiences. All the children made an overall negative assessment of IPV, referring to violence as something bad, commenting that it was an intense, harmful experience that caused them distress.

(Do you think these situations happen in your home?) Yes (and what's it like for you?) Errrr bad, I feel bad for a long time after when I see it. (Luz, 11 years old)

Individual impact

Self-concept. Most of the children describe themselves in terms of their likes and interests, related to arts (such as drawing, painting, singing, dancing and/or handicrafts) and sports (such as playing basketball and/or soccer). They also refer to various hobbies like using cellphones, going to the library, playing video games and listening to music. Three participants describe negative characteristics of themselves associated with the control of their emotions; for instance, one boy describes himself as grumpy and another girl describes herself as depressive.

At the same time, the children who directly and frequently witnessed violence from an early stage of development, particularly with severe episodes involving physical injury to the mother, describe their life's story entangled with IPV experiences.

My life's story has been complicated, my childhood, because I had to watch my mom and dad's arguments. (Rocío, 12 years old)

Furthermore, the children alluded that IPV is also an intrinsic part of some dimensions of their self-concept. Specifically, a negative self-concept emerges from their narratives, linked to a deep emotional impact caused by IPV.

Emotional impact. All but one of the children interviewed expressed negative emotions related to experiences of IPV. Most of the participants emphasize sadness, mentioning that IPV episodes caused them to cry, feel low and dispirited. They also describe feelings of despair in the face of IPV, which was reflected in the inability to effect change. One participant even describes feelings associated with depressive symptoms provoked by IPV experiences. She manifested a low level of agency, and a passive vision of the future with limited power to act and express emotions.

I felt overwhelmed, I didn't have any personal space…, it was like a dark tunnel. I didn't have a life, or a personality, or anything like that. Every time they fought, I felt sad… you're sad, you feel alone, you don't have a life, you don't have a future… I couldn't do the same, it was like I was falling into a dark hole. (María, 10 years old)

Meanwhile, another participant formed emotional regulation strategies related to his mother's safety, mentioning that, if he helped her during these IPV episodes, he felt calmer. He also told of emotions connected with IPV, indicating that he felt sad, mad, scared, nervous, ashamed, and shocked. Although he didn't want to explore these emotions further, he did reveal anxiety related to advanced responses to violent episodes that might occur at home, leaving him in a constant state of alert.

(How was it for you growing up surrounded by violence, fights, and perhaps blows inside your home?) I felt sad and mad, afraid… nervous and ashamed… also shocked (How did it make you feel?) Sadness… and concern… The only thing that made me feel better was when I helped my mother and I saw that she was ok… That kind of helps me to feel happy, to stop feeling sad. (Pedro, 9 years old)

On the other hand, one of the participants said that being exposed to IPV influenced how she was emotionally affected by conflicts in her interpersonal relationships outside of her family nucleus. For instance, she describes that when her friends fight it is unpleasant and painful, because they are important to her.

When my friends fight about nonsense, when they fight about such simple things, it's unpleasant… If one the affected people is one of my friends, it affects me as well. (Rocío, 12 years old)

Relational Impact

Relationships with extended family. The members of the extended family on the maternal side -such as grandparents, cousins, uncles and aunts- were described positively, mentioning that they were cheerful, nice, kind, loving and concerned. The participants also expressed that they had a close relationship with these people because they were a source of support and, in some cases, of protection figures during episodes of IPV.

My family is really good, generous, kind… they're not bad people (Who do you mean?) My uncles and my grandparents and cousins (From what side of your family?) Mom's… they are good people… because they are loving… they care about us. (Rocío, 12 years old)

In contrast, most of the participants describe their extended paternal family negatively, pointing out that they were not very loving, that they were authoritarian and violent. They also mentioned that, after IPV events, they did not stay much in touch, having a distant relationship because they related to each other or to the children through yelling and mistreatment, and that was unpleasant for them. One of the participants described episodes of phycological violence from their grandparents toward her and her siblings.

(What can you tell me about your dad's side of the family?) Um, I only have contact with his sister… she's really mean… she and dad always treat each other badly, they fight, they yell… (And your paternal grandparents?) They didn't like me and always yelled at us… they were bad people… they aren't affectionate, they don't even feel love for anybody … they're always bitter. (María, 10 years old)

All the above indicates that there was evident polarization in the representation of the extended paternal and maternal families in most of the narratives told by the children. The image that the children have of their parental figures after the IPV episodes at home possibly extends to the image they have of the extended paternal and maternal families.

I divide my family between my maternal and paternal family. My maternal family always, like, they always support us, help us and not always financially, umm, they are very happy, my maternal family, and, umm, my paternal family, umm ... they're often nice, but they have out-of-control episodes of fury or anger and they get very mean. (Rocío, 12 years old)

Relationship with the mother. Most of the children made positive descriptions of their mothers based on personality characteristics, such as good, happy, generous and strong. They also made positive descriptions of their role as a mother, for example, saying that they helped them with homework or cooked for them, worked and set rules at home. Most of the children described a close and reciprocal relationship with their mother, naming her their closest figure, feeling supported and protected by her.

(And who are you closest to in your family?) My mom… it's just that she's a very special person to me… she's nice to me, sweet, caring, she gets mad like anyone…else hmmm happy. (Paz, 11 years old)

The oldest participants (11 and 12 years old) described their mothers according to personality characteristics and the close affective bond they have. When describing her, one of the participants assessed her mother, mentioning that she is strong because she has been able to cope with the experiences of IPV on her own. She also refers to having a close and reciprocal relationship, that they are a team and they help each other, demonstrating the collaborative relationship that exists between them.

My mother, for me, is a very strong woman with regard to having to carry all these problems by herself ... Our relationship is very good because, as we have always said, we are a team ... good partners ... Between the two, we often help each other … She supports me in all my things, I always know that I can count on her. (Rocío, 12 years old)

One of the participants mentioned that he does not currently live with his mother but with his father; however, he mentions that his mother is his closest figure, due to the availability of her material possessions. Along with this, he comments that his relationship with his mother was better before because he used to obey her and followed her rules. What stands out in this child's narrative, on the one hand, is the identification of the mother as the person closest to him and, on the other, the acceptance and naturalization that the child expresses regarding his style of interaction with her, recognizing his oppositional, defiant and hostile behavior.

(And who are you closest to?) My mom… Because she has the TV… She has internet… (and what is your relationship like with your mom?) Now it's so-so… it was better… before, I obeyed her… now she tells me something and I say, no, you go. (Juan, 10 years old)

Relationship with the father. Half of the participants made a negative description of their father, mentioning characteristics such as a quick-tempered, mean, lying, aggressive, combative and/or not very affectionate. These representations paint a picture of a figure that is punitive and authoritarian, offering little containment or protection.

(What is your dad like?) Liar and mean ... (anything else?) No. (Clara, 9 years old)

One of the participants, along with describing her father in negative terms, refers to a negative relationship with him, describing episodes of physical and psychological violence toward her and her siblings. Another child also describes a game dynamic with violence; however, he justifies that his father does it with affection and for him to learn to defend himself. Yet another of the girls mentioned that, after IPV occurred in her home, she became more distant from her father because he had hit her mother.

(What is your dad like?) Errr he speaks with bad words, he punishes us terribly ... Before, he punished us looking at the wall, on the edge, he hurt our bodies ... When I wanted to hug him, he was always on his phone. (María, 10 years old)

… And I became more distant from my father for that reason, because he had hit my mother. (Rocío, 12 years old)

In contrast, some of the children describe the father in positive terms, two of them describing him based on physical characteristics, such as cute and chubby, and in terms of personality, such as good and nice. One of the participants also pointed out that her father is the closest figure for her, despite describing him as someone aggressive.

(What is your dad like?) My dad is chubby, cute, nice. (Paz, 11 years old)

(What is your dad like?) Aggressive ... (Who are you closest to in your family?) To my dad ... (Why is are you closest to him?) I don't know. (Luz, 11 years old)

Relationship with siblings. Most of the children in this study reported having siblings, describing a positive or negative relationship. Firstly, siblings were regarded positively as figures of protection, support and emotional containment, describing them as significant and close to them. When IPV episodes occurred at home, they took refuge in or with their siblings, carrying out activities such as playing, talking or hugging, feeling accompanied, calmer and more protected. One of the participants even describes that when she had conflicts with her siblings, they resolved them positively, through peaceful dialogue and with an intention of mutual care and respect.

Martín hugged me, protected me and Marcelo too, and we would go to the backyard ... I felt calmer with someone else, as if I was returning to normal ... we could talk about everything that happened to us ... we went to the park to relax. (María, 10 years)

Secondly, there were cases where growing up in an environment of IPV influenced a more negative relationship with siblings, based on violence. The violent dynamics that children had with their siblings included physical violence (blows) and psychological violence (yelling and insults), which occurred in everyday and/or recreational situations.

(What things make you angry?) When my brother hits me and when he takes things away from me and when they bother me when I don't do anything to him ... Sometimes ... Renato used to hit me, always like that, he hit him hard and said it was an accident and I would get involved there ... to fight with him. (Juan, 10 years old)

Relationship with peers. In general, the participants did not tend to describe their peers in their narratives; however, four of them did refer to this subject. Two of the older participants (11 and 12 years old) described that they did not go to adult figures when talking about the experiences of violence lived within their home but rather shared them with their friends. They stated that they were figures of support and containment, that they were available at all times and had a close and reciprocal relationship with them because they listened to, understood, advised, comforted and supported each other.

(Is there someone with whom you can talk about the things that have happened to you at home? Who do you trust?) With my friend who lives across the street ... with my friend ... She is eleven, she's going to be twelve ... We tell each other everything. (Luz, 11 years old)

However, two of the youngest children (9 and 10 years old) mentioned victimization by their peers. One describes it in two contexts: family (cousin) and school (classmates), coming to exert physical violence to defend themselves. The other describes this type of victimization exclusively in the school environment, carried out by her classmates.

At my school they were all bad, once a guy came to hit me ... I had an opportunity to know how to use my hands ... and my head (...) I was closer to my cousin but not now ... We became enemies through WhatsApp ... He told me … I didn't want you to have my contact details… When I was a kid, I saw him as an idol, I thought we were going to be best friends… but nothing happened. (Pedro, 9 years old)

Relationship with maternal grandmother. In the narratives of the participants, it was observed that protective figures other than mother and siblings also emerge when IPV situations occur at home. In most cases, it was the maternal grandmother, who they identified as a fundamental support figure when episodes of IPV occurred, who made them feel heard, contained and cared for.

For example, sometimes when I came home from school I felt bad because I missed my dad and my grandmother listened to me then ... if I need to tell someone something, I tell my grandmother, for example, uhhh today I miss my dad and those things when I feel sad. (Paz, 11 years old)

The maternal grandmothers even played an active, involved role in the life of their grandchildren because, on occasion, they intervened and mediated IPV situations, becoming immediate protective agents for the children.

(When you see your parents fighting, what do you do?) I call my grandmother… she lives downstairs… so she tells them to stop because look at the state in which they've got the kids. (Juan, 10 years old)

Other victimizations. With the exception of two participants, all the children described other victimizations in addition to IPV at home. In their narratives, two of the participants reveal experiences of violence in the paternal extended family. One of them described IPV among her paternal grandparents, while the other girl's story focused on physical and psychological violence between members of the paternal family, and toward her and her siblings, describing yelling and mistreatment toward them. Another girl focuses her story on the conflictive and violent relational dynamics that exist between her mother and her older sister, which has included physical violence from the mother toward her sister. She also refers to IPV that her sister suffers at the hands of her boyfriend.

(What do you think other people can do to change things at home?) My granddad should be less jealous, because once my grandma was on her cell phone, she opened Facebook and had a friend request and my granddad went and he almost hit her. (Clara, 9 years old)

(What do you think is needed to improve or change things at home?) The fights (That they get along better?) Yes (Who could get along better?) My granddad, my mom ... with granddad and grandma not to fight... I mean, no, not her now, but before, yes. (José, 8 years old)

Discussion

This study contributes to expand the development of literature in Chile and Latin America on the psychological impact associated with living in an IPV context, from the perspective of children. Through their narratives, the participants of this study show a negative impact on their emotional well-being and family relationships, some reflecting this in their descriptions of themselves and their life history in relation to experiencing chronic IPV at home. These findings support and evidence the importance of exploring the phenomenon of IPV from the perspective of the children themselves (Callaghan et al., 2015, 2017; Miranda & Corovic, 2019), highlighting their subjective experiences in relation to their victimization experiences.

Growing up in a home with IPV has been associated with an alteration of different areas of development (Howell et al., 2016). This impact could be determined by multiple factors and their interactions, which makes it difficult to establish a direct causal path leading to a specific effect (Wolfe et al., 2003). Understanding these differences, some common elements are observed in the participants' narratives, which generally show a negative impact associated with IPV, either at the emotional level or in their family relationships. This impact could be related to the fact that most of the children in this study grew up with IPV from early stages of development (seven of them register prenatal exposure) and, in turn, lived chronically with different types of IPV and other victimizations (intra- and extra-family). This could account for a cumulative effect of victimization experiences throughout their lives. Both aspects -age of onset and accumulation of violent experiences- have previously been associated with poorer mental health outcomes in children (Grahamm-Berman & Perkins, 2010; Wolfe et al., 2003). In addition, participants were recruited from the Center for Child and Youth Protection program and were undergoing legal proceedings, which may also account for the severity of the violence in which they were involved and its associated effects.

The children in this study were able to reflect that growing up in the context of IPV has an impact on an individual level in the emotional realm, and some also in their descriptions of themselves and their life history. In accordance with the literature, the children are emotionally affected by IPV between their parents, as these violent situations cause them to experience extremely powerful emotionality (Callaghan et al., 2017). In this study, children reported a state of constant and deep sadness, feelings of fear, worry, distress, and/or anger, consistent with previous international studies (Katz, 2016; Lizana, 2012; Nikupeteri & Laitinen, 2015; Save the Children, 2011). This means that IPV can become a traumatic event for children because the situation generates pain, stress and suffering (Lizana, 2012). As a traumatic experience, it could also alter beliefs about oneself, the world and others (Miranda & Corovic, 2019).

Regarding the relational impact, a polarized view of the parental figures (positive for the mother and negative for the father) was observed in the narratives of most participants, which is generalized to the view they have of their maternal and paternal extended families. In line with the literature, we can identify that, for most of the children in this study, the mother is the main caregiver (Callaghan et al., 2015; Cater & Forssell, 2014; Pernebo & Almqvist, 2017). The children described their mothers positively, reflecting an image of affection and responsibility, since they are the ones who give them care and affection, showing close and reciprocal relationships (Pernebo & Almqvist, 2017). An interesting finding refers to the protective role that some children assume toward the maternal figure (Georgsson et al., 2011; Katz, 2016), even from very early ages. For example, one of the children in this study, at age 9, refers to being concerned about his mother's welfare, commenting that he was taking actions to protect her from IPV.

In relation to the view of the father, some children have a completely negative image of their father, seeing them as authoritarian, sanctioning, offering little containment or protection (Callaghan et al., 2015; Cater & Sjogren, 2016). This reflects shortcomings in their parental role, being unable to meet the needs of their children (Barudy & Dantagnan, 2010). Meanwhile, others have a more positive and ambivalent view that, according to Aymer (2010), should be understood in the context of the IPV, where positive and negative characteristics of the father figure coexist (Aymer, 2010; Callaghan et al., 2015; Cater & Sjogren, 2016; Nikupeteri & Laitinen, 2015). Thus, they would often highlight their father's positive qualities, seeking to justify the negative behaviors, evidencing that children live with two contradictory images of their father (Peled, 2000).

An important finding of this study refers to the impact of IPV associated with the relationship with siblings. On one hand, some children describe actions of protection and mutual support with their siblings when experiencing violence. This could be related to the children's capacity of agency, i.e., the capacity to act in situations of IPV (Callaghan et al., 2015, 2017; Øverlien & Hydén, 2009), where they position themselves in a protective role toward their mothers and siblings. In this sense, agency has been described as a key element in children's and adolescents' responses to IPV episodes at home (Miranda et al., 2020; Øverlien & Hydén, 2009). On the other hand, some children described aggressive behaviors in the relational dynamics with their siblings. This is alarming, considering the high prevalence of physical abuse among siblings (McDonald & Martinez, 2019), which reaches 38% in the United States (Tucker et al., 2013). It is one of the most common types of violence within families and has long-term consequences at the mental, physical and social levels (Finkelhor et al., 2006; McDonald & Martinez, 2019).

As with the sibling relationships, participants described conflicting and positive relationships with their peers. Although it was not directly asked about in the interview, some participants reported being victims of peer violence. According to the literature, this would reflect interpersonal consequences for children who have experienced IPV at home and are likely to be victims or perpetrators of bullying (Holt et al., 2008; Lizana, 2012). Therefore, it is very important to consider IPV as a risk factor for the co-occurrence of other victimizations (Edleson, 1999; Holden, 2003; Holt et al., 2008), since poly-victimization is a common problem in children growing up in IPV contexts (Finkelhor et al., 2011).

Maternal grandmothers emerged as a protective and important figure for children in their stories. Some studies reveal that grandmothers play an important, active and involved role in the lives of children growing up in IPV contexts (Sandberg, 2013; Timonen & Arber, 2012), acting as immediate protectors and providing them with material and/or emotional support in these situations (Beeman, 2001; Sandberg, 2013). This finding may show the cultural relevance of this figure, where it is the grandmother who often gives support in the children's upbringing, allowing the parents to return to working life. She is construed as a reference for support and emotional containment, as well as authority and safety.

The limitations of this study should be considered when interpreting its results. First, caution should be taken when using semi-structured interviewing because: 1) it only provides the interviewers with an outline of questions, which gives great flexibility in the direction of the interview but also means that the amount of information obtained depends on the skill of each interviewer; 2) its questions mainly allow addressing the phenomenon of IPV, without including questions about other lifetime victimizations. Future research incorporating the poly-victimization approach would be beneficial, since our findings show that IPV should not be studied in isolation. In this regard, the international literature has reported that other forms of violence do co-occur in this population (Hamby et al., 2010), as was also observed in the children of this study. This can be considered a limitation to the extent that, when experiencing other forms of victimizations, it is not possible to completely isolate the exclusive impact of IPV through participants' narratives. We therefore consider it important for future research to investigate the experiences of children with different levels of exposure to IPV. Considering that each child was interviewed once, future research could include more than one encounter with each participant in order to develop a longitudinal analysis around their experiences with IPV. We also recognize the small sample size as a limitation, and that they belong to the Child and Youth Protection program in a specific region of our country. In this sense, our findings do not necessarily represent the experiences of children who do not attend these programs or those who have not experienced chronic IPV.

Regarding the implications of the study, it is important for children who grow up in contexts with IPV to be considered in clinical, legislative and research settings not only as witnesses, but as direct victims of this type of violence. This is especially urgent given the negative impact that this type of violence can have on the children's lives. In clinical settings, we suggest that mental health professionals who work with both adult (women and men) and child populations should routinely include screening to identify early on what children are growing up or have grown up in homes with IPV. We also suggest that, in the evaluation process, clinicians be alert to other experiences of victimization that children who have grown up in households with IPV may have suffered, given the high co-occurrence that has been documented. Additionally, the findings of this research may be useful in guiding clinicians in the design of relevant interventions for children with IPV histories. In this regard, it is important not only to develop psychotherapeutic processes that contribute to overcoming the effects associated with IPV, but also to highlight the need to follow up on the cases. In this sense, this study confirms the contributions that clinical research can make to achieve the challenge of interrupting the cycle of violence in this generation and the next. According to recent data (United Nations (UN) Women, 2020), the current global context of the COVID-19 pandemic and health emergency has significantly aggravated the problem of IPV, heightening the urgency of ensuring assistance and support services against this type of violence. Finally, we suggest that future research should include broader and more heterogeneous samples, with the purpose of accessing and understanding a greater diversity of subjectivities, including other axes in the analysis, such as gender.

texto en

texto en