Introduction

Emotional intelligence is an important and rapidly growing area of research at the current time (Fernández-Berrocal et al, 2018), although its conceptualisation and measurement are the source of some controversy (Mayer et al, 2008). Nonetheless, one of the most widely used definitions views emotional intelligence as the ability to control emotions, differentiate them and use the resulting information to guide thoughts and behaviour (Salovey & Mayer, 1990), or, more specifically, the ability to perceive emotions, access and generate emotions facilitating thought, understand and be aware of emotions, and regulate emotions (Mayer & Salovey, 2007).

Research on emotional intelligence began in the 1990s and was led by Salovey and Mayer (1990), although it was not until the end of the last decade and beginning of the current decade that the first concrete attempts were made to empirically observe its effects on people (Extremera & Fernández-Berrocal, 2004), such as improving intrapersonal and interpersonal wellbeing and fostering an ability to control one’s own emotions and those of others in a given situation (Rauf et al, 2013).

Research has focused on establishing the usefulness of the construct in a number of key areas, with the aim of demonstrating the ways in which it shapes behaviour and the areas in which it has a significant influence (Extremera & Fernández-Berrocal, 2004). The emotional intelligence skills described in Mayer and Salovey’s (1997) model are emotional perception, emotional understanding, emotional facilitation and emotional regulation. These skills influence various spheres of life. Thus, the ability for emotional repair (Hodzic et al, 2016) interacts with stress in predicting life satisfaction in high-stress situations: subjects with the poorest emotional repair skills are less satisfied with their lives. Meanwhile, a negative correlation is observed between neuroticism and various aspects such as emotional management and control (Enríquez, 2011), as people with greater emotional intelligence also display greater empathy and lower levels of emotional inhibition (Ramos et al, 2007).

It is important to emphasise the correlation between emotional intelligence and social relations (Martin-Raugh et al, 2016). Statistically significant differences in terms of patterns of social behaviour have been observed between profiles, with subjects belonging to groups with high overall emotional intelligence and high levels of emotional regulation displaying higher scores in positive social behaviours (Gázquez et al, 2015). The ability to regulate emotions is associated with a healthy personality. In a study examining the optimum profile for extrinsic regulation, inter-regulation or hetero-regulation (Company et al, 2012), the authors observed that it consisted of aspects such as high situation modification, the ability to de-dramatise and distract oneself, the ability to make a cognitive change at the appropriate time, the absence of repression of others, the ability to avoid uncontrolled interactions, the ability to avert conflict, and high expression regulation or assertiveness.

There is, therefore, a correlation between emotional intelligence and positive or disruptive social behaviour. Some studies (Saadi et al, 2012) show that training in emotional intelligence reduces aggression and enhances the capacity for individual and social adaptation. This data demonstrates the necessity of implementing programmes to develop and improve emotional intelligence on a preventive basis in order to avoid violence.

Through its constructs, emotional intelligence allows the socioemotional characteristics influencing different behaviours linked to cyberbullying profiles to be ascertained (Bernal & Ramírez, 2019). In this respect, it is important to consider the significant rise in cases of cyberbullying associated with the development of new information technologies and the emotional backdrop underpinning the issue. The use of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) is an inherent part of modern societies, providing a tool facilitating necessary processes of communication and socialisation (Polo del Río et al, 2017) and helping to maintain interpersonal relations, forge emotional bonds and foster closeness in communication (Colás et al, 2013). The spread of this form of technology has displaced traditional spaces for socialisation (Díaz-Gandasegui, 2011), leading to changes to conventional types of bullying (Heirman & Walrave, 2009), with new characteristics such as the anonymity of the aggressor, the scope and size of the audience and the inability to escape (Valera, 2012). Cyberbullying can extend into the victim’s own home, removing the existence of safe spaces and provoking a sense of helplessness and vulnerability (Polo del Río et al, 2017). This form of abuse occurs in the context of other cyberbullying behaviours based on the relationship of domination/submission between the individual abusing his or her power and the target of their abuse (Avilés et al, 2011). It consists of intentional, recurrent aggression, drawing regularly on digital forms of social contact to reach the victim (León et al, 2012).

Cyberbullying may therefore be defined as the use of ICT, especially mobile telephones, to harass peers (Garaigordobil & Aliri, 2013). In this context, the intensive use of smartphones is a source of concern (Gómez et al, 2014) as it conditions social relationships (Bianchi & Phillips, 2005; Kamibeppu & Sugiura, 2005) and leads to behavioural, emotional and social problems (Pedrero et al, 2012). It is for this reason that increasing numbers of researchers are conducting research with the aim of exploring the consequences when cyberbullying is mediated by the use of information and communications technology (Elipe et al., 2012). As we know, cyberbullying has a significant impact on coexistence, because it replaces mutual respect and moral reciprocity with abusive forms of domination and submission (Ortega, 2010). In this regard, some studies link emotional intelligence to cyberbullying, aiming to detect deficiencies in emotional competencies and maladjustment in aggressive individuals in order to design specific interventions to improve their condition (Montoya et al, 2011). With this in mind, being a victim of cyberbullying can lead to significant emotional and psychological imbalances, affecting areas of great importance such as life satisfaction (García et al, 2019).

Research has demonstrated a correlation between high levels of antisocial behaviour and involvement in cyberbullying in any role (as a victim, aggressor or spectator) and the use of more aggressive strategies as a way to resolve interpersonal conflicts (Garaigordobil, 2017). In this context, perceived emotional intelligence is a moderating variable between cybervictimisation and emotional impact, as it either increases or reduces this impact, while cyberbullying provokes negative emotions in victims (Elipe et al, 2015). In any case, a deficiency in the ability to perceive the emotions of others may lead individuals to attribute erroneous intentions to other people in social interactions and to assess situations in a more negative manner than an individual with good emotional perception skills (García-Sancho et al, 2015). It also gives rise to a lack of social self-efficacy and low levels of social development in aggressors (Romera et al, 2016)

On the basis of this empirical evidence, cyberbullying encompasses emotional indicators, such as emotional distress among victims and aggressors (Ybarra & Mitchell, 2004), which suggest that it may indicate a lack of empathy (Ortega et al, 2009). It is important to note that there is a correlation between suffering bullying and subsequently perpetrating it (Avilés et al., 2011; Romera, Del-Rey & Ortega, 2011), as cybervictimisation is linked to involvement in bullying as an aggressor (Elipe et al, 2012). A study focusing on secondary school pupils showed that individuals involved in bullying are perceived as unable to manage their emotions, with the victims displaying the weakest ability to understand and manage them (Elipe, 2012).

Other relevant aspects to consider when studying cyberbullying are gender and age differences. With regard to gender, the data are inconclusive. Some studies find no correlation between the two variables (Finn, 2004). Others observe a significant association between cyberbullying and gender (Li, 2006), noting that men commit more acts of cyberbullying (as the aggressors) while women tend to occupy the role of the victim (Calvete et al, 2010; Finn & Banach, 2000). Meanwhile, the age variable has been the main focus of research on cyberbullying to date. Studies have shown a particular interest in cyberbullying among adolescents and university students (Sticca, Ruggieri, Alsaker & Perren, 2013; Elipe, 2012), who are considered to be the groups most at risk (Weare, 2004). However, recent research has demonstrated that adults who participate in cyberbullying display higher incidences of behaviours classified as verbal abuse (Betts et al, 2019).

This article aims to explore the phenomenon of cyberbullying and provide information on its prevalence in adults in terms of gender and age. Drawing on previous research among children, adolescents and young people, the main objective of this article is to use logistic regression analysis to investigate the mediating effect of emotional intelligence in relation to cyberbullying among adults, creating models to predict cybervictimisation and cyberaggression based on inadequate Perceived Emotional Intelligence (PEI). In this context, and in light of empirical evidence linking deficiencies in emotional intelligence with cyberbullying, the authors hope to uncover differences based on the involvement profile.

Methodology

Participants

Sampling was not probabilistic for the sake of convenience, as the aim of the researchers was to gain access to the largest possible number of adult subjects with knowledge of and access to information technologies. In order to achieve this, 5,300 subjects enrolled on a MOOC (Massive Open Online Course) were invited to participate. A total of 848 Spanish-speaking adults of 15 nationalities (14 Latin American n = 478; and Spanish n = 370) were recruited, of whom 79.9% were women and 23.1% were men, with an average age of 40.52 (SD = 11.65). 45% of the sample were aged between 21 and 30 (young adults: M = 24.45; SD = 2.91) while 55% were aged between 31 and 62 (adults: M = 45.45; SD = 8.43).

Instruments

European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire (ECIPQ). To establish types of involvement in cyberbullying, the Spanish version (Ortega-Ruiz et al, 2016) of the European Cyberbullying Intervention Project Questionnaire (ECIPQ) (Del Reyet al., 2015) was used. The ECIPQ encompasses 22 items with a Likert-type scale offering five response options, ranging from 0 to 4 (0 = never, 1 = once, 2 = once or twice a month, 3 = around once a week, and 4 = more than once a week). The questionnaire examines two dimensions: cybervictimisation and cyberaggression, with high levels of reliability (total α = .87, victimisation α = .80, aggression α = .88). For both dimensions, the items refer to actions such as swearing, spreading rumours, impersonating others, etc., all via electronic media and covering the two months prior to participation in the study. The profiles - victim, aggressor, victim/aggressor and no profile (not involved) - were identified by cross-referencing the responses to both questions. Participants were considered to be victims if they scored ≥2 on victimisation and 0 on aggression; aggressors if they scored 0 on victimisation and ≥2 on aggression; victim-aggressors if they scored ≥2 on both dimensions; and no profile (not involved) if they scored ≤1on both dimensions.

Trait Meta Mood Scale-24, (TMMS-24) (Salovey & Mayer, 1990). In order to evaluate perceived emotional intelligence, the Spanish version of the Trait Meta Mood Scale-24 questionnaire was used (TMMS-24, Fernández-Berrocal et al., 1998). This instrument allows perceived intrapersonal emotional intelligence to be measured or, in other words, it provides a personal assessment on reflexive aspects of individual emotional experience (Salovey, Mayer, Goldman, Turvey & Palfai, 1995). The questionnaire includes 24 items, with a Likert-type scale offering 5 response options (1= Strongly disagree, 5= Strongly agree). It assesses three different dimensions (8 items per dimension): Attention to feelings (the ability to feel and express feelings adequately); Clarity of feelings (understanding of emotional states) and Mood repair (adequate emotional regulation). The reliability for each component is Attention (α = 0.90); Clarity (α = 0.90); Repair (α = 0.86), demonstrating adequate test-retest reliability.

Procedure

MOOCs offer thousands of adults the opportunity to access online courses free of charge. These educational programmes allowed us to access a sample of adults who use information technologies. Via the miradax.net platform, students enrolled on MOOCs in July 2017 were asked to participate in the study. The TMMS-24 and ECIPQ questionnaires were administered online via the Google Forms application (a Google Drive tool). In accordance with the ethical guidelines issued by the American Psychological Association (APA, 2009), all participants gave their informed consent before completing the questionnaires, guaranteeing the anonymity and confidentiality of the data and their exclusive use for research purposes.

Data analysis

The SPSS 21.0 programme was used to perform statistical analysis on the collected data. The reliability of the instruments used was calculated using Cronbach's alpha. Descriptive analyses were carried out and, after checking assumptions of normality and homocedasticity, a multivariate analysis (MANOVA) and binomial regression analysis were performed.

Results

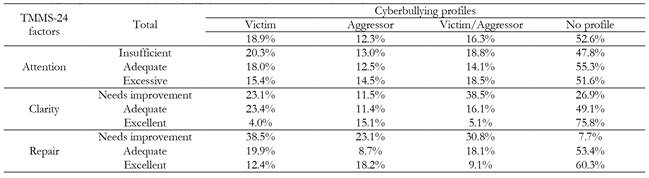

Firstly, the distribution of the participants on the basis of their cyberbullying profiles and levels of Attention, Clarity and Repair is presented (Table 1).

Table 1: Distribution of participants on the basis of cyberbullying profiles and levels of Attention, Clarity and Repair.

With regard to cyberbullying, it is relevant to note that almost half of the participants had experienced cybervictimisation or cyberaggression: 35.2% of the participants had suffered cyberbullying, while 28.6% admitted to perpetrating cyberbullying (Table 1). Comparisons of these percentages revealed differences by gender, χ2 = 16.611(3), p < .001, in the profiles of victim (women = 17.2%; men = 24.5%), aggressor (women = 13.5%; men = 8.2%) and no profile (women = 54.9%; men = 44.9%), and age, χ2 = 30.041(3), p < .001, in the profiles of aggressor (young people = 18.3%; adults = 9.6%), victim-aggressor (young people = 25.8%; adults = 14.2%) and no profile (young people = 38.7%; adults = 57.1%).

With regard to PEI, comparisons of the attention, clarity and repair groups with the cyberbullying profile showed differences in Clarity, χ2 = 56.584(6), p < .001, and Repair, χ2 = 36.091(6), p < .001, and were equivalent in Attention, χ2 = 4.184(6), p = .652. In this respect, 73.1% of the subjects involved in cyberbullying required improvement in terms of Clarity while 92.3% needed to improve their Repair (Table 1).

In order to confirm whether the TMMS-24 displayed any differences in relation to the cyberbullying profile, a multivariate analysis (MANOVA) was performed, which revealed significant multivariate main effects of the profile on the analysed variables (Wilks λ = .877, F(9. 2049) = 12.635, p < .001, ƞ = .043). The univariate contrasts demonstrate the existence of a significant main effect of the cyberbullying profile on the factors Clarity (F(3. 844) = 34.713, p < .001, ƞ = .110) and Repair (F(3. 844) = 17.169, p < .001, ƞ = .058). In addition, the multiple comparisons performed indicate that in both the Clarity and Repair factors on the TMMS-24: 1) the subjects without a specific profile obtained higher scores (p < .05) than subjects with victim and victim/aggressor profiles (Clarity: No profile-Victim p < .001; No profile-Victim/aggressor, p < .001; Repair: No profile-Victim, p = .011; No profile-Victim/aggressor, p < .001). 2) aggressors obtained higher scores (p < .05) than victim/aggressors (Clarity, p = .018; Repair, p = .005).

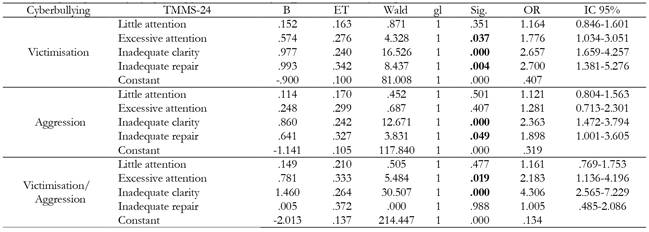

Once the existence of a correlation between emotional intelligence and the four cyberbullying profiles had been confirmed, the researchers attempted to ascertain whether or not emotional intelligence was able to significantly predict victimisation and cyberaggression. In order to determine the TMMS-24 variables which most precisely predict cyberbullying, a binary logistic regression analysis was performed (Table 2). The analysis included the factors Attention, Clarity and Repair as predictor variables, grouped as dichotomous variables (pays: little attention; excessive attention; inadequate clarity or inadequate repair, yes/no).

Table 2: Results of the logistic regression analysis for predicting cybervictimisation and cyberaggression on the basis of inadequate EI.

Three predictive models were created (Table 2). The predictive model for cybervictimisation allows a correct estimate to be made in 67.7% of cases (χ2 = 47,546(4), p < .001), while the model for cyberaggression allows for a correct estimate in 71% of cases (χ2 =29.329(4). p < .001) and the model for cybervictimisation/aggression allows for a correct estimate in 83.7% of cases (χ2 =39.982(4). p < .001). The setting value for the models was between 5.5% and 7.5% for the victimisation model (Cox & Snell R2 = .055; Nagelkerke R2 = .075), between 3.4% and 4.9% for the aggression model (Cox & Snell R2 =.034; Nagelkerke R2 = .049) and between 4.6% and 7.8% for the victimisation/aggression model (Cox & Snell R2 =.046; Nagelkerke R2 = .078). The odds ratios for the logistic models show that: 1) the probability of being a victim is 77.6%, 166% and 170 % greater in subjects with excessive attention, inadequate clarity and inadequate repair respectively, 2) the probability of being an aggressor is 136% greater in subjects with inadequate clarity and 190% greater in subjects with inadequate repair, 3) the probability of being a victim/aggressor is 118% greater in subjects with excessive attention and 330% greater in those with inadequate clarity.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the correlation between PEI and cyberbullying in adults. Firstly, the distribution of the participants on the basis of their cyberbullying profiles and PEI was analysed, examining potential differences in the various cyberbullying profiles by gender and age. After the presence of differences in PEI between individuals who were involved and not involved in cyberbullying was confirmed, the mediating effect of emotional intelligence on the profiles involved in cyberbullying - victim, aggressor or victim/aggressor - was analysed.

With regard to cyberbullying, the study followed the approach taken by previous studies (Elipe et al., 2009; Polo et al., 2017) by differentiating between subjects who were involved and not involved in cyberbullying, as well as dividing those involved by profile: victims, aggressors and victim/aggressors. Almost half of the participants had been involved in cyberbullying in the two months prior to the study. This demonstrates that the rise of cyberbullying and the normalisation of violent behaviour exerted via social media and electronic devices (Li et al., 2012) affects both young people and adults.

In terms of the influence of gender and age on cyberbullying, the findings of previous studies have been inconsistent and even divergent on the matter of gender.

A number of studies observe no differences by gender (Finn, 2004; Katzer et al., 2009; Sentse et al., 2015). Others demonstrate that men are more commonly involved than women (Durán & Martínez, 2015; Navarro et al., 2016), while others still indicate the contrary (Holfeld & Grabe, 2012). However, in most cases, as in this study, the findings corroborate the presence of gender differences in cyberbullying. More specifically, the results show that while the percentage of women involved in cyberbullying is generally lower than that of men, the percentage of female aggressors and male victims is higher. This corroborates the findings of other studies, which observed that men are more likely to be victims of cyberbullying than women, (Gofin & Avitzour, 2012; Pelfrey & Weber, 2013), diverging from those which found that women are more often victims (Brighi et al., 2012; Fenaughty & Harré, 2013; Olenik-Shemesh et al., 2012). Another group of studies observe no differences in victimisation by gender (Caballo et al., 2012; Monks et al., 2012). It is thus difficult to generalise on the relationship between gender and cyberbullying.

In terms of age, the findings demonstrate far greater involvement in cyberbullying as aggressors and victim/aggressors among young people. This confirms that young people are the group at greatest risk (Weare, 2004), as their use of mobile telephones is more extensive than that of people in other age groups (Kubey et al., 2001; Morahan-Martin & Schumacher, 2000; Treuer et al., 2001). However, no differences were found with regard to involvement as a cybervictim, suggesting that both age groups experience similar levels of vulnerability to cyberbullying and indicating that victimisation is a particularly relevant variable when studying cyberbullying in adults.

With regard to the comparisons between PEI and cyberbullying profiles, it is relevant to note that most of the participants in the study whose Clarity and Repair needed improvement, that is, those who had difficulty understanding and regulating their emotional states, were involved in cyberbullying. Among those involved, victims and victim/aggressors displayed the lowest levels of understanding and regulation of their emotional states. On this matter, a number of studies indicate the presence of significant differences between those involved and not involved in bullying, with those involved displaying poorer emotional repair skills. Victims in particular are characterised by greater attention and poorer clarity and repair (Elipe et al., 2009).

Moreover, the results of the regression analysis confirm that PEI is useful in distinguishing between the various profiles of subjects involved in cyberbullying among adults, largely corroborating prior research focusing on younger people (Ortega et al, 2009). In the case of victims more specifically, they may be differentiated from other individuals involved in cyberbullying by their intense attention to their emotions and weak ability to understand and regulate their own emotions. Meanwhile, aggressors are characterised by poor skills in understanding and regulating their own emotions, confirming the lack of social self-efficacy present in this group (Romera et al., 2016). On this matter, Guerra et al. (2019) find that individuals with poor clarity and weak emotional repair skills are most likely to perceive themselves as unhappy, which could go some way to explaining the relationship between an inadequate PEI and aggressive behaviour and cyberbullying.

On the other hand, victim/aggressors differ from the other profiles due to their excess of emotional attention and weak ability to understand their own emotions. These findings corroborate other studies which associate high attention with inadequate clarity (Extremera & Fernández-Berrocal, 2005) and demonstrate a clear link between clarity and repair (Extremera et al., 2007). They also show that, given the correlation between being a victim of cyberbullying and subsequently perpetrating it (Avilés et al., 2011; Elipe et al. 2012; Romera et al., 2011), it is relevant to identify individuals who are victim/aggressors and differentiate them from those who are either victims or aggressors when researching the phenomenon (Polo et al. 2017). However, it is important to recall that a deficiency in the ability to perceive emotions makes it more difficult to interpret others’ intentions, giving rise to potential errors in evaluating certain behaviours (García-Sancho et al., 2015). This offers a partial explanation for the fact that it is inadequate clarity which has predictive power over the three cyberbullying profiles analysed.

Among the limitations of this study, it is important to emphasise the bias inherent in the use of self-reports as a single data collection method, as well as the bias inherent in the transversal study design, which makes it more difficult to make greater inferences on the correlation between the study variables. Meanwhile, the scarcity of previous research on cyberbullying among adults hinders discussion of the findings, while confirming the innovative nature of research on this topic. Despite these limitations, these findings may serve as a starting point for subsequent studies, demonstrating the need to pay closer attention to the phenomenon of cyberbullying among adults and to study it in greater depth, while also enhancing training and prevention programmes aimed at both young people and adults.

Finally, given the significance of emotional intelligence as a factor in protecting individuals from cyberbullying, it is recommended that emotional education is incorporated into any actions taken to prevent and/or minimise cyberbullying behaviours. In this regard, Kırcaburun et al. (2019) highlight the importance of implementing programmes for adults to improve social connection, self-esteem and group membership and reduce depression as a protective element against participation in cyberbullying.