Introduction

Since December 2019, the world has been facing a new, highly contagious virus called SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). From June to July 1st, 2020 (the period when this study was conducted), Spain, a country of 47.329,981 habitants, had a total of 275,178 people confirmed as infected by the virus, with 29,393 deaths. Poland, with 38,383,000 habitants, had 34,775 infected and 1,074 deaths due to the disease (Worldometer, 2020). The rapid spread of infections, the risk of mortality and associated health problems, together with the economic and social implications derived from lockdown, have generated discomfort and frustration in society (Vallejo-Slocker et al., 2020).

Current studies have confirmed the increase in levels of psychological distress (comprising stress, anxiety and depression, according to Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) in various countries due to the impact of the pandemic and restrictive quarantine measures (Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020; Verma & Mishra, 2020). Likewise, two recent meta-analyses found differences by gender and age and reveal that the Coronavirus crisis not only causes physical health problems but also seriously affects the mental health of the general population (Pappa et al., 2020; Salari et al., 2020). Specifically, some recent studies show that the prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic is higher in women than in men due to the former’s higher tendency to use maladaptive coping strategies (Rahman et al., 2020). Despite the increased health risk and higher mortality from COVID-19 infection in elderly individuals (60 years or more), the results of recent research show that levels of depression, anxiety and stress are higher in middle age (21-40 years) working adults (Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020; Justo-Alonso et al., 2020). Some studies indicate that the main reason for this seems to be that this age group is more affected by the economic consequences of the pandemic (Ahmed et al., 2020).

In view of the increase in affective disorders in the face of the current COVID-19 pandemic, resilience and coping processes may play a key role in preventing them (León et al., 2020; Lew et al., 2019). Different longitudinal and cross-sectional studies have shown that resilience is an important buffer against stress, generalized anxiety and depressive symptoms when facing adverse situations (Barzilay et al., 2020). According to Olsson et al. (2003), this dynamic process of adaptation to a risk situation implies an interaction between a range of personal and social risk and protection factors. In this sense, emotional regulation processes stand out as a personal protective factor (Koole, 2009). It has been shown that the inability to regulate emotions contributes to the development of psychopathologies (Domaradzka & Fajkowska, 2018). Particularly, the term ‘cognitive emotion regulation strategies’ (CERS) refers to the conscious and cognitive way of managing the intake of emotional arousal information (Garnefski et al., 2001). Garnefski et al. (2002) established 9 Cognitive Emotional Regulation Strategies (CERS) grouped into 2 categories: adaptive and maladaptive. Maladaptive strategies include self-blame, rumination, catastrophizing, and blaming others; they are consistently related with anxiety, stress and depression. In contrast, adaptive strategies such as positive refocusing, refocus on planning, positive reappraisal, acceptance and putting into perspective are associated with the reduction of psychopathological symptoms (Aldao and Nolen-Hoeksema, 2010; Garnefski & Kraaij, 2006, 2007) and adequate interpersonal functioning during stressful events (Limonero et al., 2014).

Culture can determine the motivation to employ emotional regulation processes as well as adaptability to a context (Ford & Mauss, 2015). Following Lazarus and Folkman (1984), cultural values, beliefs, and norms influence the process of evaluating stressors and the perceived appropriateness of coping responses. Huppert & So (2013) found striking differences between European countries in flourishing rate, which relates to ten positive aspects of mental functioning: competence, emotional stability, commitment, meaning, optimism, positive emotion, positive relationship, resilience, self-esteem and vitality. All the Nordic countries scored the most favorably. South/West European countries such as Spain scored in the middle, while Eastern European countries like Poland were in the lower half. Cultural factors can act as a buffer against environmental stressors, or they increase stress levels and influence psychopathological symptoms (Dar, 2017; Cockerham et al., 2006). From the Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1977), it is understood that the intention to perform a behavior depends on the attitudes (beliefs, intentions, social pressure, etc.) of people to carry out such behavior. Likewise, behavior depends on the subjective norms shared in each cultural context and on people's motivation to adapt to them, something that conditions affective responses. Following Páez & Zubieta (2005), Spain is a Mediterranean, south-western European country in which physical contact is relevant for people, and social relationships are characterized by greater closeness. In Eastern European countries such as Poland, greater emphasis is placed on independence and physical autonomy. These relational characteristics influence the social representation of emotions in each context. Thus, in Mediterranean countries such as Spain, where emotional regulation processes are favored, the expression of positive emotions (sympathy, empathy, modesty, humility) to the endogroup acquires greater relevance. In contrast, in countries like Poland the trend is greater expressiveness of negative emotions and greater direct confrontation with others. Sociocultural differences could have a different effect on the psychological distress experienced by populations during lockdown in each country (Germani et al., 2020; Knyazev et al., 2017).

In summary, in an international public health emergency like the one we are experiencing during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is important to investigate its psychological impact on different seriously affected populations such as Poland (European Eastern) and Spain (European Mediterranean/South-Western). Taking gender and age into account, the present study aims to compare psychological distress (depression, anxiety and stress), resilience, as well as the use of CERS as a coping strategy during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in both countries. Finally, the study proposes cross-cultural predictive models of psychological distress depending on socio-demographics, resilience and CERS.

Method

Participants

The sample is composed of a total of 1,182 adults (over 18 years old) from Poland (50.8%: 40.3% male, 59.7% females) and Spain (49.2%: 17% male, 82.9% female). We calculated age range categories on the basis of the cut-off points obtained in previous COVID-19 meta-analysis studies, in which affective mental health consequences appear to be more prevalent in those aged 21 - 40 years (Salari et al., 2020). So, in this study we will work with groups aged 18 - 20 years (Young; Poland: 13.8%, Spain: 5.8%), 21 - 40 years (Middle; Poland: 75.8%, Spain: 46.2%), and 41+ years (Elderly; Poland: 10.3%, Spain: 47.8%).

Instruments

All the methods used have been well validated in each country. All participants responded on the basis of the COVID-19 lockdown situation in the last few months (March to July 2020). Cronbach’s alphas in this study for each country were adequate and are presented in Table 2.

Cognitive Emotional Regulation Questionnaire (CERQ; Garnefski & Kraaij, 2002; Spanish version of Domínguez-Sánchez et al., 2011; Polish version of Marszał-Wiśniewska & Fajkowska, 2010). This questionnaire measures the cognitive emotion regulation strategies used by individuals after the occurrence of a negative event. It consists of 36 items, each of which has five response options ranging from ‘Almost never’ (1) to ‘Almost always’ (5). Nine cognitive strategies are evaluated: Rumination, Catastrophizing, Self-blame (not applied in this study), Blaming Others, Putting into Perspective, Acceptance, Positive Focusing, Positive Reinterpretation and Refocusing on Plans, with four items each. Also, two major factors can be obtained with good reliability: Maladaptive (the first four strategies) and Adaptive strategies (Martin & Dahlen, 2005).

Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995; Spanish version of Bados et al., 2005; Polish version of Makara-Studzińska et al., n.d.) This instrument measures psychological distress according to the tripartite model of anxiety, depression, and stress. It consists of a set of three self-report scales designed to assess negative emotional states related to depression, anxiety, and stress (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). Additionally, a total factor can be obtained. Each of the three DASS-21 scales contains seven items with 4-point Likert-type scales, from 0 = ‘Does not apply to me’ to 3 = ‘Most of the time’.

The Brief Resilience Coping Scale (BRCS; Sinclair & Wallston, 2004; Spanish version of Limonero et al., 2014); Polish version of Piórowska et al., 2017) It comprises four items that assess the ability to cope with stress in an adaptive manner, measured on a 5-point Likert scale (1= ‘the statement does not describe me at all’ to 5 = ‘the statement describes me very well’).

Procedure

This study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013) and included informed consent, thus ensuring anonymity throughout the process and the option to quit at any moment. The 10-minute questionnaire was completed online. It requests participants to think about the recent months (March to June 2020) since the COVID-19 pandemic started. Participants received the invitation to the questionnaire through email and social networks; they were asked to share it with others with a minimum age of 18 years (snowball method).

Data Analysis

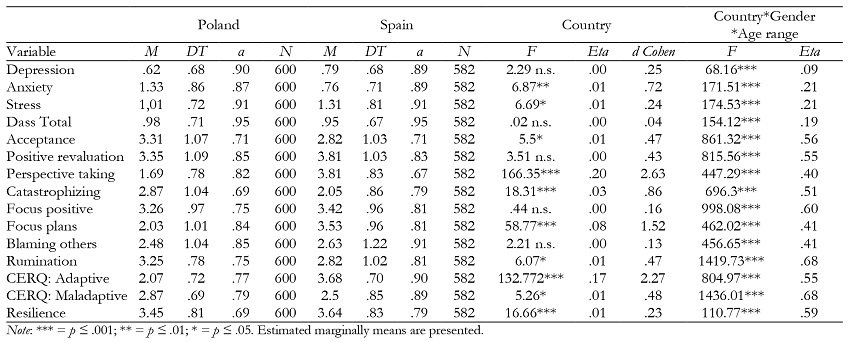

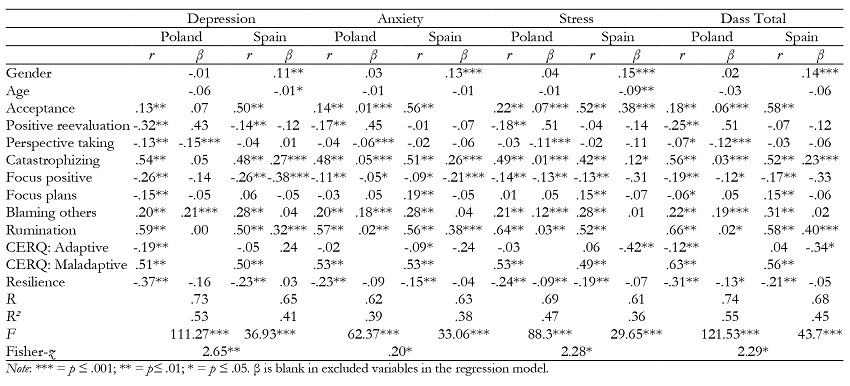

We carried out descriptive analysis of the sample, segmented by country (Table 1); this was followed by Pearson Chi-Square analysis to examine gender- and age-related differences between samples. Reliability was obtained for each subscale with the use of Cronbach’s alpha analysis (Table 1). MANOVA analysis was conducted to study differences between criterion variables (depression, anxiety, stress, CERS and resilience) depending on the country (Table 1). To give a better overview of these results, effect sizes as estimated by Cohen’s d were calculated. After this, we carried out a MANCOVA, thus repeating the previous analysis but controlling for gender and age range (Table 1). Pearson correlations (Table 2) were carried out between all criterion variables (CERS and resilience) and dependent variables (depression, anxiety, stress, and total DASS score) in each country. Then, a linear regression analysis (Table 2) using the Enter method and segmented by country was conducted to analyze the prediction of dependent variables; criterion variables, controlled for gender, and age were inserted. Differences in the magnitude of the associations between countries were examined by testing the difference between two independent correlations based on Eid, Gollwitzer & Schmidt (2011).

Results

Descriptive analysis and Chi-Square for gender and age

The descriptive results of the sample segmented by country (Table 1) show low psychological distress means in both countries and high resilience means, although Polish participants suffer more anxiety while Spanish participants experience more stress. CERS variables show that Polish participants show high means in using strategies of acceptance, positive reevaluation and rumination, but they less frequently use perspective taking and refocusing on plans. On the other hand, Spanish individuals show higher means in general, with lower scores in catastrophizing, rumination, blaming others and acceptance. Polish participants score higher in maladaptive strategies, while Spanish participants score higher in adaptive ones. Chi-Square values show significant differences in gender (OR: 77.99, p ≤ .001) and age ranges (OR: 203.22, p ≤ .001) between these countries’ samples, so we will take them into account in the following analysis.

MANOVA analysis according to country, and MANCOVA, controlling for gender and age

The MANOVA analysis revealed significant differences between these countries in most of the study variables (Table 2). Polish participants suffered more anxiety while Spanish ones suffered more stress, but there were no significant differences in depression and total DASS score. Regarding CERS, there are no significant differences in the use of positive reevaluation, positive focusing and blaming others. Spanish participants show significant differences in adaptive strategies: they more often refocus on plans and use perspective taking. In contrast, Polish participants use more maladaptive strategies such as catastrophizing and rumination, although they also show more acceptance. This result is confirmed by significant differences in Spanish individuals’ resilience. Cohen’s d analysis (1988) shows that the significance of these differences is small for most variables but is medium-sized for anxiety and large for catastrophizing, refocusing on plans, perspective taking and adaptive CERS (Table 1). While taking into account the effect of gender and age on the MANCOVA analysis, we found significant differences in all variables that were not significant in the previous analysis, and the power increases in all factors (Table 1). For this reason, we will control for the effect of gender and age on dependent variables in the next regression analysis, which is segmented by country.

Pearson correlations and linear regression analysis by country

As we can observe in Table 2, in both countries there are significant correlations between resilience, most CERS variables, and psychological distress. First, depression correlates with all variables in Poland and Spain, with the exception of refocusing on plans and general adaptive strategies in the latter. Anxiety is correlated with variables in both countries, especially in Poland, with the exception of positive reevaluation, perspective taking, and blaming others in Spain, as well as focus on plans and adaptive strategies in both countries. Stress shows significant correlations with most variables in both countries, with the exception of positive reevaluation in Spain, focus on plans in Poland, and perspective taking and adaptive strategies in both countries. The total DASS score of psychological distress correlates with all variables in both countries, with the exception of positive reevaluation, perspective taking and adaptive strategies in Spain. Most significant correlations with resilience and adaptive strategies were negative, while significant correlations with maladaptive strategies were positive. Acceptance, however, correlates in a positive way with depression, anxiety, stress and total DASS in both samples.

Complete regression models for each country are shown in Table 2. In general, regression analysis shows different prediction models of psychological distress for each country, although we found similar results that identify catastrophizing and rumination as relevant predictors in both countries. Important differences appear related to sociodemographic variables; in particular, female gender and higher age are predictors only in Spain. Some general factors are significantly predictive only in one of the compared countries, such as adaptive strategies in Spain and resilience in Poland. However, the general maladaptive strategies factor is not predictive in either country. Comparing the correlation analysis between these countries shows significant differences in all dependent variables (Table 2)

Discussion

The objective of this study was to analyze the differences between Poland and Spain in resilience, cognitive regulation of emotions, as well as psychological distress during the Coronavirus pandemic lockdown in these adult populations.

Regarding the differences between countries, a higher level of anxiety was observed in the Polish sample compared to the Spanish one; this could be explained by the fact that the Polish sample uses maladaptive strategies more frequently than adaptive ones. Specifically, Polish participants used more catastrophizing, which consists of thoughts that anticipate exaggerated or disproportionate consequences, and rumination, which is defined as thinking excessively about the feelings or problems associated with the occurrence of a negative event (Domínguez & Medrano, 2016). In terms of resilience and the impact of CERS on psychological distress, this study showed that Polish citizens use the perspective-taking strategy to a lesser extent (relativizing the seriousness of a negative event; Medrano et al., 2013) and suffered from higher levels of depression, anxiety, stress and general psychological distress. Other risk factors in the Polish population included the less frequent use of the positive focus strategy (maintaining pleasant and happy thoughts after an unpleasant event; Garnefski & Kraaij, 2007), increased use of maladaptive CERS, such as catastrophizing and rumination strategies, and the use of blaming others (cognitive process of causal attribution of an unpleasant event to other people; Dominguez y Medrano, 2016). According to a meta-analysis (Aldao et al., 2010), maladaptive strategies and the decreased use of adaptive strategies in the process of cognitive regulation of emotions are consistently related to psychological distress. This could explain the Polish sample’s low level of resilience, which is a predictive factor of stress and general psychological distress (Agnieszka et al., 2020; Domaradzka & Fajkowska, 2018). Regarding the adaptive CERS, it should be noted that Polish participants showed more acceptance than their Spanish counterparts during the COVID-19 pandemic. Likewise, greater acceptance was predictive of higher levels of anxiety, stress and general psychological distress in the Polish population. Acceptance refers to a cognitive process that consists not in trying to change or control unpleasant emotions or events but in experiencing them by accepting them without judgement (Domínguez & Medrano, 2016). Previous studies found a positive association between this strategy and affective disorders (Kraaij et al., 2002; Martin & Dahlen, 2005). Thus, some authors point out that acceptance could be adaptive only in certain circumstances, possibly depending on the type of mood being considered (Martin & Dahlen, 2005). In this sense, this emotional regulation strategy could be related to the assumption of a state of hopelessness in the face of the current crisis.

Secondly, the Spanish population experienced a higher level of stress compared to the Polish one; this could be explained by the fact that older age and female gender appeared as risk factors of psychological distress in this sample. These results are in line with recent studies (Ozamiz-Etxebarria et al., 2020) which indicate that both being older and female gender increase the risk of psychological distress due to the greater possibility of unemployment, the difficulties of reconciling work/telework with family life, and fear of getting sick from COVID-19. As seen in previous literature (Aldao et al., 2010) and similarly to Poland, for Spanish participants catastrophizing and rumination were risk factors of depression, anxiety, stress and general psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly to Poland, less frequent use of the positive focus strategy was a risk factor of depression and anxiety for Spaniards, and acceptance positively predicted greater stress in this sample. This surprising result may be related to a sense of hopelessness and unpredictability caused by the pandemic. Various studies indicate that intolerance to uncertainty, fears about the future, how long the restrictive measures will last, exposure to the media, etc, are powerful predictors of psychological distress during the COVID-19 lockdown (Cedeño et al., 2020; Sandín et al., 2020). Our results could explain the population's effort to try to regain a perception of control during the COVID-19 pandemic and to try to come to terms with this difficult situation. Despite this, the use of this strategy as a way to regulate unpleasant emotional states is dysfunctional and even counterproductive, probably because there is a relationship between acceptance and the activation of ruminative thinking during a stressful life period like the current one (Ehring, & Ehlers, 2014).

On the other hand, the Spanish population reported higher resilience and greater use of adaptive strategies for cognitive regulation of emotions than the Polish one. Spanish participants were also more likely to take perspective and refocus on plans. In this sense, relativizing the seriousness of a negative event and applying thinking strategies that focus on solving the problem (Domínguez & Medrano, 2016) are cognitive emotional strategies related to greater tolerance to negative experiences (Aldao et al., 2010). This is why our results support the idea that adaptive coping strategies could explain the Spanish sample’s higher resilience score (Polizzi, et al. 2020). In fact, in this study adaptive CERS was only a protective factor of stress and general psychological distress in the Spanish population. It could be assumed that Spanish people regulate their emotions better to deal with adverse situations and succeed in the face of the challenges posed by the current pandemic. These differences between Poland and Spain could be explained by the Theory of Reasoned Action (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1977), from which it is understood that subjective norms shared in each cultural context condition behaviors. In this sense, research on reappraisal suggests that distinct emotion-regulation strategies probably operate quite differently depending on the culture (Kwon et al., 2013). For example, countries with Mediterranean culture like Spain are characterized by aspects such as closeness and physical contact, socializing in public spaces, and a feeling of unity that reinforces social ties between the population (Mizrahi, 2020). Some studies suggest that individuals in Mediterranean countries are more likely to foster positive social relationships and use reevaluation and resilience strategies more than individuals from Eastern countries (Huppert & So, 2013), probably because in this context adapting emotions to the social environment acquires greater relevance (Butler, 2007).

Despite differences in anxiety and stress, both of which are related to physical hyperarousal and negative affect, we did not find differences in depression levels, which is related to the absence of positive affect (Henry & Crawford, 2005). This result could be explained due to Poland and Spain are countries with individualistic cultures, characterized by more open social relationships unlike collectivist cultures (Páez & Zubieta, 2005). Some studies have pointed out that independent or individualistic personal self-construction is negatively associated with depression (Knyazev et al., 2017), which could explain the lack of significant differences in depression between Poland and Spain.

Our results must be interpreted cautiously in the context of certain methodological limitations. It should be noted that it would be desirable for the samples to be more demographically homogeneous between the countries. In addition, it is recommended that future studies examine the adaptive or maladaptive nature of the acceptance strategy in traumatic situations such as the current pandemic. Likewise, in addition to CERS and resilience, other personal variables can possibly be studied, such as personal protective factors (e.g. trait and ability emotional intelligence or personality traits) that influence the prevention of psychological distress.

In conclusion, these two countries have experienced and coped with the COVID-19 lockdown in different ways, thus confirming the mental health consequences of the pandemic and the cultural differences in the emotional regulation strategies used to cope with it. We believe that the insights gained from this study could benefit initiatives for the promotion of psychological well-being as a way to prevent psychopathological disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study also provides guidance concerning the levels of psychological distress that these populations are likely to experience in this kind of critical situation, guiding interventions when cultural diversity should be taken into account.