Mi SciELO

Servicios Personalizados

Revista

Articulo

Indicadores

-

Citado por SciELO

Citado por SciELO -

Accesos

Accesos

Links relacionados

-

Citado por Google

Citado por Google -

Similares en

SciELO

Similares en

SciELO -

Similares en Google

Similares en Google

Compartir

The European Journal of Psychiatry

versión impresa ISSN 0213-6163

Eur. J. Psychiat. vol.19 no.3 Zaragoza jul./sep. 2005

Professional secrecy as a stressor among norwegian physicians

| Lise Løvseth, MA, Research Associate* Olaf G Aasland, MD, PhD, Professor** K Gunnar Götestam, MD, PhD, Professor*** * Norwegian University of Science and Technology, |

Key words: Professional secrecy, Stress, Physician, Social support.

ABSTRACT - The aim of the present study is to assess how the necessary practice of professional secrecy may be a stressor for doctors, and to what extent MM (mortality and morbidity)-meetings and having a doctor as a spouse or partner, may serve as outlets for emotional charge.

A postal survey was sent to a stratified sample of 780 doctors working in and outside hospitals in a health region in Norway (1.1 million inhabitants). With a response rate of 46 percent (358 / 780), 22 percent of the respondents were identified as being high on stress and low on coping. 26 percent of the doctors participated regularly in MM-meetings. The risk of being stressed increased with increasing score on the scale for perceived lack of possibilities to discuss emotionally charged issues at work and at home. The doctors who participated in MM-meetings had a significantly reduced stress risk. Having a doctor as partner did not affect the stress level significantly. The results indicate that MM-meetings are effective in stress reduction among Norwegian doctors and should be a self-evident part of ordinary clinical activities.

Introduction

To communicate our thoughts seems to be a fundamental phenomenon in life, and a number of authors have pointed out that expression of emotion is vital to physical and psychological health (Goleman 1995, Kennedy-Moore & Watson 1999, Pennebaker 1989). According to Pennebaker (1990) inhibition is an act of restraining a given behaviour that would normally take place, which in fact can be hard work. Studies have shown that inhibition of such behaviour is associated with increased physiological activity (Waid & Orne 1982, Pennebaker & Chew 1985), which, like other stressors, may gradually undermine the body's defences and immune function. To hold back thoughts, feelings, and behaviour may place people at risk for disease. However, communicating normally with other human beings may improve both physical and mental health through receiving other people's help, attention and understanding (Lazarus 1966, Pennebaker 1990). In addition, talking to others gives us a sense of security and belonging (Maslow 1970, Jourard 1971, Cobb 1976), reorganises our thoughts, and creates meaning and new knowledge from our experiences (Horowitz 1976, Silver, Boon & Stones 1983, Pennebaker 1990). This is probably the reason why putting more or less emotionally upsetting experiences into words is such a natural human response, occurring in all arenas and in all aspects of everyday life.

On the one hand, medical physicians are probably aware of this phenomenon through daily practice where patients often offer more information than absolutely necessary for diagnosis and treatment, but on the other hand physicians must probe into people's most secretive areas, both physically and emotionally. As a consequence, the physician-patient situation presupposes confidentiality and protection of sensitive information. The medical environment is characterised by several psychological factors that generally are shown to produce stress, and that various physician-patient interactions can affect physicians to a great extent (Robinson 1984, Aasland & Falkum 1992, Arnetz 2001, Kälvemark, Höglund, Hansson, Westerholm & Arnetz 2004). Receiving emotional input and private information about other people may act as a stressor. As a result, some patient situations may elicit emotions of anger, frustration, avoidance, fear and despair that in turn generate the need for coping. However, coping with these emotions and how they handle the load of sensitive and at times upsetting information within the framework of professional secrecy has not been the subject of much research. Although this is a familiar situation, it is likely that the practising of professional secrecy may be a source of strain by inhibiting the physicians' possibility to talk about situations that affect them.

The aim of the present study is to look at physicians' perception of professional secrecy as a potential constraint on their professional and private roles. Do physicians perceive professional secrecy as an obstacle for social- and personal support and coping? Given the judicial constraints of professional secrecy among health personnel, there is reason to believe that when colleagues are the primary source of personal support, then professional secrecy will have little influence on perceived strain. But when social support comes from outside the collegial network, such as partner, family or friends, then the professional secrecy may be a greater obstacle for the ability to cope. We want to investigate whether physician-to-physician discussions, typical for so-called morbidity and mortality meetings (MM-meetings), can alleviate stress and improve coping. We also want to investigate whether a more informal situation where emotionally charged matters can be related and discussed, as at home with a spouse or partner who is also a physician or health-worker affected by the same rules of professional secrecy, may be of importance.

Material and methods

A postal questionnaire was sent to 780 practising physicians working under Central Norway Regional Health Authority. The respondents were drawn from the master file of the Norwegian Medical Association, stratified in order to obtain an equal number of physicians working in and outside hospitals. The selection of respondents was based on an estimated response rate of 40 % to secure 150 respondents in each category.

The questionnaire contained 136 questions or statements about professional secrecy, work environment, social support, job satisfaction, stress, coping and information on age, gender, years of practice and partner's occupation, and the data served as a basis for a master thesis in psychology. The present paper is based on a selection of the data from this project. The analyses are performed with frequency tables and stepwise logistic regression.

The dependent variable of this study is dichotomous and constructed through the combination of responses to one question on stress and one on coping. The stress question, to be answered on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much) was: "To what extent do you regard your work as a stressor?" The coping question, to be answered on a scale from 1 (poorly) to 5 (very well) was: "How do you find that you cope with stress and strain in your work?" The physicians who answered 3 or higher on the stress question and 3 or lower on the coping question were defined as "cases".

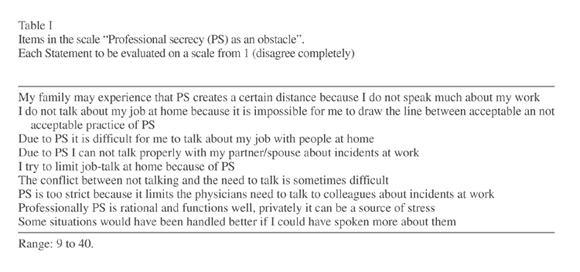

A measure of how rules of professional secrecy are seen as an obstacle to discuss emotionally charged incidents at work and at home was constructed as a simple summary index with scores from nine questions, as shown in Table I. The variable is called "Professional secrecy as an obstacle".

A factor that may affect stress due to lack of acceptable "outlets" is whether the physicians have regular mortality and morbidity meetings (MM-meetings). These are semi-formal meetings, usually for physicians only, where complicated cases and adverse incidents are discussed. We therefore include a variable that indicates the presence or absence of MM-meetings.

Another situation that may potentially influence the stress generated by the practice of professional secrecy is when the spouse is a physician, nurse or other health worker. Hence we also include the spouse's profession, as one of the following five categories: physician, nurse, other health worker, and other professions.

Results

The response rate was 46 % (358/780), 65 % males and 35 % females. Mean age was 44 years (range 27-67), and the average number of years since authorisation 17 (range 1-41). 53 % (188/358) of the physicians worked in hospital settings. Twenty six percent (92/356) participated in regular MM-meetings. The professions of the spouses are given in Table II. 22 % (78/358) of the respondents were identified as "cases" with regard to stress and coping, as described above.

Table III gives the results of the stepwise logistic regression. The first model included gender, age, and workplace (hospital/outside hospital). In the second model we included the measure of how professional secrecy is perceived as an obstacle to freely discussing emotionally charged incidents and situations, and in the third model we included the two potential alleviators, MM-meetings and spouse's profession. As expected, the experience of not being able to discuss emotionally charged incidents and situations increases the risk of stress significantly, and the presence of MM-meetings reduces this effect significantly. As for the partner's profession, it is better to have a partner than not to have one (all coefficients are negative). However, it is not particularly advantageous to have a physician-partner. The best partner in this respect is actually a nurse, with a close to significant negative effect on the stress measure.

Discussion

The relatively low response rate of the present study calls for some caution in generalising the results. However, the age and gender distribution among the respondents is similar to what is found in a representative group of working Norwegian physicians. Since many of the physicians work in the same hospital departments, or in the same practitioner groups, the units are not completely independent. The same goes for physician partners, most physician couples in the study are likely to be represented with their individual data with no possibility to control for the fact that they give support to each other. However, we cannot see that this fact invalidates our analyses.

Physicians may use many coping strategies to deal with stressful circumstances at work in relation to professional secrecy. In the present study we focus on coping by using significant others for social support and assistance (Thoits 1986). Even though physicians use a number of sources of support, the primary providers for talking about stressful circumstances at work are physician colleagues and family. These findings are consistent with research identifying colleagues and superiors as the primary sources of coping with stress at work (Cobb 1976, Thoits 1986, Cohen 1987, Karasek & Theorell 1990), and that family may compensate for work-related strain on the external arena (House 1981, Pearlin & Turner 1987).

Christensen, Levinson and Dunn (1992) found that sharing feelings with a spouse who is also a physician has proved beneficial, because both technical as well as emotional issues could be more openly discussed, and that such a partner might be perceived as judicially "safe". In our study a nurse partner more than a physician partner seemed to give this effect.

The most important finding, however, is the clear and positive effect of MM-meetings. Only one in four physicians presently enjoy this opportunity, which should be self-evident for all physicians, particularly in a world where ethical dilemmas and moral distress is an increasing part of physicianing (Kälvemark et al. 2004). A professional culture where the fundamental uncertainty of medical practice and the vulnerability of the physician, as well as the need for support and the possibility to "speak out" are acknowledged should be the aim for all members of the profession, as well as for their managers and politicians.

Informal outlets for emotional charge may be a good alternative to formal meetings. Confidential talks between physicians behind closed doors can be a satisfactory way of handling emotional reactions among physicians at the work place, as it is necessary to take into account the large variety in individual needs (Vincent 1999).

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank First Amanuensis, Pål Ulleberg, for support on analyses and Scientific advisor, Professor Arne Vikan for editorial assistance. The Central Norway Regional Health Authority, through Medical Advisor Inge Romslo, and The Sickness Compensation Fund of the Norwegian Medical Association for core funding of the main survey. Last but not least participants in the study both in preliminary interviews and survey, and respondents of the main survey.

Contributors

L. Løvseth planned the study, designed the questionnaire, collected the data and performed most of the analyses. OG Aasland sampled the physicians, gave advice on the questionnaire and the original analyses, revised an original version of the paper, and performed some of the final analyses. Professor K. Gunnar Götestam for editorial assistance and critical revision of the study proposal.

References

Aasland OG, Falkum E. How are we today? On physicians' health, well-being and work satisfaction. [Hvordan har vi det i dag? Om legers helse, velferd og jobbtilfredshet] Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 1992; 112: 3818-3823. [ Links ]

Arnetz B. Psychosocial challenges facing physicians of today. Soc Sci Med 2001; 52: 203-213. [ Links ]

Christensen JF, Levinson W, Dunn P M. The heart of darkness: the impact of perceived mistakes on physicians. J Gen Intern Med 1992; 7: 424-431. [ Links ]

Cobb S. Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom Med 1976; 38: 300-314. [ Links ]

Cohen F. Measurement of Coping. In: Kasl SV, Cooper CL eds. Stress and Health: Issues in Research Methodology. New York: John Wiley & Sons Ltd 1987; 283-305. [ Links ]

Goleman D. Emotional intelligence. London: Bloomsbury; 1995. [ Links ]

Horowitz M J. Stress response syndromes. New York: Jacob Aronson; 1976. [ Links ]

House JS. Work stress and social support. Reading (Massachusetts): Addison Wesley; 1981. [ Links ]

Jourard SM. Self-disclosure: an experimental analysis of the transparent self. New York: Wiley & Sons; 1971. [ Links ]

Kälvemark S, Höglund AT, Hansson MG, Westerholm P, Arnetz B. Living with conflicts: ethical dilemmas and moral distress in the health care system. Soc Sci Med 2004; 58: 1075-1084. [ Links ]

Karasek R, Theorell T. Healthy work: stress, productivity, and the reconstruction of working life. USA: Basic Books; 1990. [ Links ]

Kennedy-Moore E, Watson JC. Expressing emotion. New York: Guilford; 1999. [ Links ]

Lazarus RS. Psychological stress and the coping process. New York: McGraw - Hill; 1966. [ Links ]

Løvseth L. How does professional secrecy affect physicians? An investigation of the physicians' personal experience of practising professional secrecy related to coping of stress factors in their work. [Masterthesis in Norwegian], Department of Psychology, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim. Norway; 2002. [ Links ]

Maslow AH. Motivation and Personality. New York: Harper & Row Publishers; 1970. [ Links ]

Pearlin LI, Turner HA. The family as a context of the stress process. In: Kasl SV, Cooper CL eds. Stress and health: issues in research methodology. New york: John Wiley & Sons Ltd 1987; 143-65. [ Links ]

Pennebaker JW, Chew CH. Behavioural inhibition and electrodermal activity during deception. J Pers Soc Psychol 1985; 49: 1427-1433. [ Links ]

Pennebaker JW. Emotion, disclosure and health. New York: American Psychological Association; 1989. [ Links ]

Pennebaker JW. Opening up. The healing power of expressing emotions. New York: The Guilford Press,; 1990. [ Links ]

Robinson R. Health and stress in ambulance services. Melbourne: Social Biology Resources Centre; 1984. [ Links ]

Silver RL, Boon C, Stones MH. Searching for meaning in misfortune: making sense of incest. J Soc Issues 1983; 39: 81-102. [ Links ]

Thoits P. Social Support as Coping Assistance. J Consult Clin Psychol 1986 ; 54: 416-423. [ Links ]

Vincent C. Fallibility, uncertainty and the impact of mistakes and litigation. In: Firth-Cozens J, Payne R. eds. Stress in health professionals. New York: John Wiley & Sons LTD 1999; 63-78. [ Links ]

Waid WM, Orne MT. Reduced electrodermal response to conflict, failure to inhibit dominant behaviors, and delinquent proneness. J Pers Soc Psychol 1982; 43: 769-774. [ Links ]

Address for correspondence:

Lise Løvseth, MA, Research Associate.

Norwegian University of Science and Technology,

Institute of Neuroscience,

PO Box 3008, Lade

7441 Lade, Norway

E-mail address: lise.lovseth@ntnu.no

NORWAY